1 Integrating a “Sustainability Exploration” Into Community Health Curriculum: Medical Students Investigate Effects of Climate and Environment on Community Health

Liz Sopdie

Background

The Rural and Metropolitan Physician Associate Programs (RPAP/MetroPAP) are 9-month longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC) programs in the University of Minnesota Medical School. LICs are a model of clinical education that integrates clerkship experiences (family medicine, pediatrics, OB/GYN, psychiatry, etc.) for medical students who are embedded in a community or location for a longer period of time than traditional “block” clerkships of medical school that require students to change clerkship experience and/or location every 4-8 weeks. RPAP/MetroPAP accepts 30-40 students per year, who spend 9 months of their third year of medical school in a rural or urban underserved community across Minnesota for clinical education. Students are able to form longer-term relationships with patients and their physician mentors (preceptors), and learn first-hand the challenges and benefits of either rural medicine or urban medicine. There is a particular emphasis on social determinants of health and primary care, especially family medicine, in RPAP and MetroPAP.

Students and preceptors in an RPAP community.

As part of a broader asynchronous curriculum, RPAP and MetroPAP students complete a Community Health Curriculum that takes them through the process of learning about their new community, connecting with local community partners, identifying a community-driven need, and designing, implementing, and evaluating a project. At the end of the RPAP/MetroPAP experience, students write a reflective paper and present a poster about their experience. Assignments are scaffolded from November to June to take students through a scoping guide, project proposal, ethical considerations discussions, a final paper, evaluation by their community partner, and the poster presentation.

Although students are asked to investigate health needs in their community and consider social determinants of health, there is no explicit connection made with the environmental aspects that affect health. This project aimed to integrate a “sustainability exploration” component into the existing Community Health Curriculum to allow students to explore how components of climate, environmental health, and planetary health affect patient care (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Planetary Health. “What is Planetary Health?”

The Project

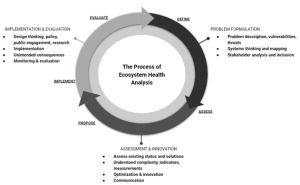

Following an ecosystem health approach (see figure 2) that aims to tackle complex challenges that affect humans, animals, and the environment, this project was designed to integrate a focus on sustainability into the ‘problem formulation’ phase of the student assignments. It is particularly important to understand all facets of a system when exploring the problem description and stakeholder analysis/inclusion, and this assignment was designed to explicitly address environmental aspects of medicine and how climate change is affecting rural and urban communities.

Figure 2: An Ecosystem Health Approach. The Sustainability Exploration was integrated in the “problem formulation” stage.

To accomplish this, I performed a literature scan of sustainability in medical education and spoke with key stakeholders in the medical school to identify existing resources for sustainability education (see figure 3). I then developed and implemented plans for integrating these components into the Community Health curriculum.

| Literature Scan: Climate/Environment/Sustainability in Healthcare and Medical Education |

|

Figure 3: Literature scan. See references at the end of this case study.

The Sustainability Exploration component is something that could be easily adapted to another context or course approach. I designed it to be specific to the context of healthcare and medical education with the readings, and to be a “micro-assignment” with low stakes evaluation (pass/no pass, graded for completion) within part of a larger existing curriculum so that students wouldn’t feel burdened or see this assignment as extra work. By incorporating the Sustainability Exploration in the beginning of the overall Community Health curriculum and specifically in the problem formulation stage of project design, it acts as a lens through which students can view their communities and community health challenges.

Sustainability Exploration Assignment

I designed a new assignment component within the Community Health curriculum titled a “Sustainability Exploration” with the following components:

- Learn: US healthcare system’s impact on public health

- Learn: Climate change & health slides developed by Planetary Health Alliance partners at University of Minnesota

- Review the “Introduction and Resources” slides AND choose 3 “Climate Change and Health” topics to review in detail (exploration of other topics is optional; ~6 slides in each topic).

- Reflect & synthesize: review resource on integrating planetary/environmental health into clinical guidelines and apply information learned to community

- Submit a ~500 word/1 page (single spaced) reflection that includes both of the following:

- Something new that you learned from the “Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health” article, something surprising, or a lingering question you have;

- Using the “Panel: Dimensions to consider when integrating planetary health into clinical guidelines” from this article (“Integrating planetary health into clinical guidelines to sustainably transform health care”) as a resource, reflect on how you would propose to apply the information you learned in the “Climate Change and Health” slides to your clinical assessment (environmental/exposure questions, recommendations, etc.).

- Submit a ~500 word/1 page (single spaced) reflection that includes both of the following:

I also added questions related to sustainability and climate health into the existing project scoping guide and project proposal assignments:

Example of question in scoping guide: “What environmental factors are crucial in this community? For example, what is the air or water quality in the community? Have there been recent severe weather events in recent years, or periods of extreme heat or extreme cold?”

Example of question in project proposal: “Social Factors and Community Partners: What social and environmental factors are crucial to your case? For example, consider availability of safe walking paths or presence of allergens/air pollutants if advocating for more exercise, or other social determinants of health. What resources, stakeholders, and expertise in the community do you need? Identify, by name, one or more potential project partners in your community with whom you will collaborate to address the health issue you chose.”

Project Assessment

The Sustainability Exploration is in its first year of implementation (fall 2022) and results so far are positive. Students completed the assignment requirements and noted several things they learned and were surprised to learn while completing the assignment. They also made explicit connections to their own RPAP/MetroPAP communities and how climate affects patient health (allergens, tick-borne illness, air and water quality, etc.). Students also connected what they learned to their own Community Health projects and discussed new aspects to explore related to environmental health when designing their interventions. The assignment is evaluated on completion (pass/no pass) and there is no formal rubric.

Examples from student reflections, shared with permission:

“…what was surprising to me was that the deaths lost due to health care-related emissions are of the same order of magnitude as the amount of harm caused from preventable medical errors. If this is the case, how is this not discussed more in medical education?”

“My first thought is that it would be important to consider the emotional and physical impacts that things like environmental degradation and severe weather can have on people of a community. Especially living in an agricultural community, changes in climate and severe weather events can significantly impact peoples’ livelihoods. This can lead to challenges with finances, food, family, housing, and many other social determinants of health that directly impact the physical and mental health of people in a community.”

“…it surprised me that Lyme’s disease incidence was doubled in less than 20 years. With the temperature difference and the spread of vector boundaries, more and more people will become infected. Knowing this, I am more aware that I will have to further educate my patients on the prevalence and things to watch out for in regard to vector borne illnesses.”

“In terms of my CHA project, I had not previously thought about including any of these things in my assessment of the community. However, after thinking about them, I think that many of these issues probably play a role in the community than I had previously thought. My region has several lakes that are surrounded by farmlands, but is also starting to have increasing rates of urbanization as the Twin Cities suburbs continue to move outward. I think that this is actually a more important thing to consider in this community, particularly because of how quickly it is growing in size.”

Students presenting their Community Health projects at the end of the 2022 program year.

Competencies and Frameworks Used

This project was based off of the ecosystem health framework referenced above in figure 2, and the competencies below from “A brand-inclusive competency framework for education at the animal-human-environment interface: Competency Domains, Subdomains, and Competency Examples” created by the University of Minnesota Ecosystem Health Working Group.

- Domain: Leadership

- Domain: Inquiry

- Domain: Values and Ethics

- Subdomain – Cross-Cutting Concept: Health, Welfare, Wellbeing

References

- Individualized Pathways: Rural Physician Associate Program. Rural Physician Associate Program.Retrieved November 21, 2022 from https://med.umn.edu/md-students/individualized-pathways/rural-physician-associate-program-rpap

- Individualized Pathways: Metropolitan Physician Associate Program. Metropolitan Physician Associate Program.Retrieved November 21, 2022 from https://med.umn.edu/md-students/individualized-pathways/metropolitan-physician-associate-program-metropap

- Poncelet, A. N., Mazotti, L. A., Blumberg, B., Wamsley, M. A., Grennan, T., & Shore, W. B. (2014). Creating a longitudinal integrated clerkship with mutual benefits for an academic medical center and a community health system. The Permanente journal, 18(2), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/13-137

- Atwoli, L., Baqui, A. H., Benfield, T., Bosurgi, R., Godlee, F., Hancocks, S., … Vázquez, D. (2021). Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. The Lancet, 398(10304), 939–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01915-2

- Bell, E. J. (2010). Climate change: What competencies and which medical education and training approaches? BMC Medical Education, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-31

- Moore, J. E., Mascarenhas, A., Bain, J., & Straus, S. E. (2017). Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0637-1

- Motzer, N., Weller, A. R., Curran, K. D., Donner, S., Heustis, R. J., Jordan, C., … York, A. (2021). Integrating programmatic expertise from across the us and canada to model and guide leadership training for graduate students in sustainability. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168950

- Virtanen, P. K., Siragusa, L., & Guttorm, H. (2020). Introduction: toward more inclusive definitions of sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 43, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2020.04.003

- Colbert, C. Y., French, J. C., Brateanu, A., Pacheco, S. E., Khatri, S. B., Sapatnekar, S., … Salas, R. N. (2021). An Examination of the Intersection of Climate Change, the Physician Specialty Workforce, and Graduate Medical Education in the U.S. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2021.1913417

- McKinnon, S., Breakey, S., Fanuele, J. R., Kelly, D. E., Eddy, E. Z., Tarbet, A., … Ros, A. M. V. (2021). Roles of Health Professionals in Addressing Health Consequences of Climate Change in Interprofessional Education: A Scoping Review. The Journal of Climate Change and Health. Elsevier Masson SAS. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100086

- McGonigle, K., & Gill, F. (2020). Preparing U.S. medical students to respond to climate change. Social Medicine, 13(3), 166–170.

- Sopdie, E. ., Wolf, T. ., Spicer, S. ., Kennedy, S. ., Errecaborde, K. M., Colombo, B. ., Jordan, C., & Travis, D. . (2021). Ecosystem Health Education: Teaching Leadership Through Team-Based Assignments. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 21(6). https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v21i6.4385

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge and extend my gratitude to the following people for their support of this project:

Kirby Clark

Barrett Columbo

Laalitha Surapaneni

The Planetary Health group at UMN

The Ecosystem Health Working Group at UMN

Joe Warren