24 Laws of Inheritance and Single-Gene Inheritance

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the relationship between genotypes and phenotypes in dominant and recessive gene systems

- Use a Punnett square to calculate the expected proportions of genotypes and phenotypes in a monohybrid cross

- Explain Mendel’s law of segregation and independent assortment in terms of genetics and the events of meiosis

- Explain the purpose and methods of a test cross

- Identify non-Mendelian inheritance patterns such as incomplete dominance, codominance, multiple alleles, and sex-linked genes from the results of crosses

Lecture Videos

The lecture videos for this chapter are embedded throughout.

The seven characteristics that Mendel evaluated in his pea plants were each expressed as one of two versions, or traits. Mendel deduced from his results that each individual had two discrete copies of the characteristic that are passed individually to offspring. We now call those two copies genes, which are carried on chromosomes. The reason we have two copies of each gene is that we inherit one from each parent. In fact, it is the chromosomes we inherit and the two copies of each gene are located on paired chromosomes. Recall that in meiosis these chromosomes are separated out into haploid gametes. This separation, or segregation, of the homologous chromosomes means also that only one of the copies of the gene gets moved into a gamete. The offspring are formed when that gamete unites with one from another parent and the two copies of each gene (and chromosome) are restored.

For cases in which a single gene controls a single characteristic, a diploid organism has two genetic copies that may or may not encode the same version of that characteristic. For example, one individual may carry a gene that determines white flower color and a gene that determines violet flower color. Gene variants that arise by mutation and exist at the same relative locations on homologous chromosomes are called alleles. Mendel examined the inheritance of genes with just two allele forms, but it is common to encounter more than two alleles for any given gene in a natural population.

Phenotypes and Genotypes

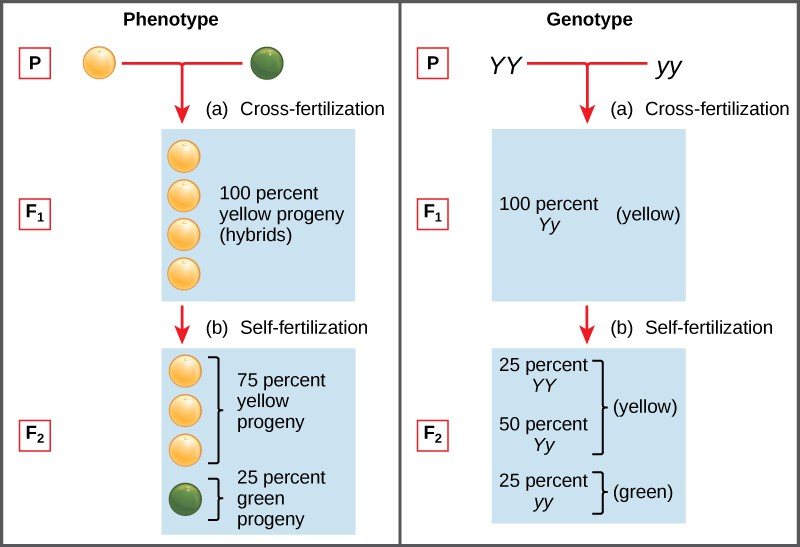

Two alleles for a given gene in a diploid organism are expressed and interact to produce physical characteristics. The observable traits expressed by an organism are referred to as its phenotype. An organism’s underlying genetic makeup, consisting of both the physically visible and the non-expressed alleles, is called its genotype. Mendel’s hybridization experiments demonstrate the difference between phenotype and genotype. For example, the phenotypes that Mendel observed in his crosses between pea plants with differing traits are connected to the diploid genotypes of the plants in the P, F1, and F2 generations. We will use a second trait that Mendel investigated, seed color, as an example. Seed color is governed by a single gene with two alleles. The yellow-seed allele is dominant and the green-seed allele is recessive. When true-breeding plants were cross-fertilized, in which one parent had yellow seeds and one had green seeds, all of the F1 hybrid offspring had yellow seeds. That is, the hybrid offspring were phenotypically identical to the true-breeding parent with yellow seeds. However, we know that the allele donated by the parent with green seeds was not simply lost because it reappeared in some of the F2 offspring (Figure 1). Therefore, the F1 plants must have been genotypically different from the parent with yellow seeds.

The P plants that Mendel used in his experiments were each homozygous for the trait he was studying. Diploid organisms that are homozygous for a gene have two identical alleles, one on each of their homologous chromosomes. The genotype is often written as YY or yy, for which each letter represents one of the two alleles in the genotype. The dominant allele is capitalized and the recessive allele is lower case. The letter used for the gene (seed color in this case) is usually related to the dominant trait (yellow allele, in this case, or “Y“). Mendel’s parental pea plants always bred true because both produced gametes carried the same allele. When P plants with contrasting traits were cross-fertilized, all of the offspring were heterozygous for the contrasting trait, meaning their genotype had different alleles for the gene being examined. For example, the F1 yellow plants that received a Y allele from their yellow parent and a y allele from their green parent had the genotype Yy.

Law of Dominance

Our discussion of homozygous and heterozygous organisms brings us to why the F1 heterozygous offspring were identical to one of the parents, rather than expressing both alleles. In all seven pea-plant characteristics, one of the two contrasting alleles was dominant, and the other was recessive. Mendel called the dominant allele the expressed unit factor; the recessive allele was referred to as the latent unit factor. We now know that these so-called unit factors are actually genes on homologous chromosomes. For a gene that is expressed in a dominant and recessive pattern, homozygous dominant and heterozygous organisms will look identical (that is, they will have different genotypes but the same phenotype), and the recessive allele will only be observed in homozygous recessive individuals (Table 1).

| Homozygous | Heterozygous | Homozygous | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | YY | Yy | yy |

| Phenotype | yellow | yellow | green |

Mendel’s law of dominance states that in a heterozygote, one trait will conceal the presence of another trait for the same characteristic. For example, when crossing true-breeding violet-flowered plants with true-breeding white-flowered plants, all of the offspring were violet-flowered, even though they all had one allele for violet and one allele for white. Rather than both alleles contributing to a phenotype, the dominant allele will be expressed exclusively. The recessive allele will remain latent, but will be transmitted to offspring in the same manner as that by which the dominant allele is transmitted. The recessive trait will only be expressed by offspring that have two copies of this allele (Figure 2), and these offspring will breed true when self-crossed.

Lecture Video: Dominance (complete/incomplete), Mendelian traits.

Monohybrid Cross and the Punnett Square

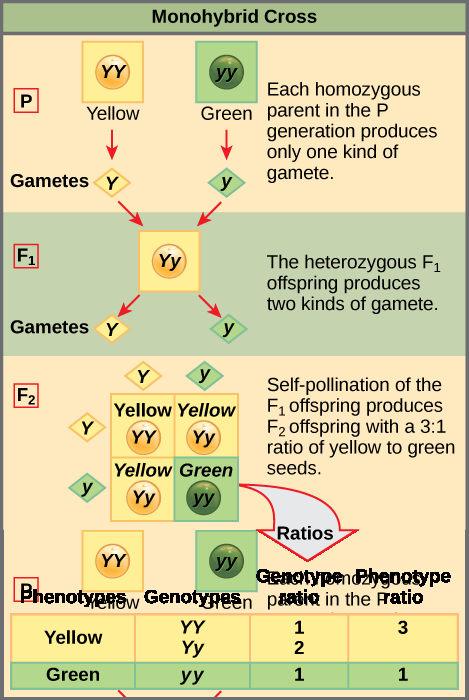

When fertilization occurs between two true-breeding parents that differ by only the characteristic being studied, the process is called a monohybrid cross, and the resulting offspring are called monohybrids. Mendel performed seven types of monohybrid crosses, each involving contrasting traits for different characteristics. Out of these crosses, all of the F1 offspring had the phenotype of one parent, and the F2 offspring had a 3:1 phenotypic ratio. On the basis of these results, Mendel postulated that each parent in the monohybrid cross contributed one of two paired unit factors to each offspring, and every possible combination of unit factors was equally likely.

The results of Mendel’s research can be explained in terms of probabilities, which are mathematical measures of likelihood. The probability of an event is calculated by the number of times the event occurs divided by the total number of opportunities for the event to occur. A probability of one (100 percent) for some event indicates that it is guaranteed to occur, whereas a probability of zero (0 percent) indicates that it is guaranteed to not occur, and a probability of 0.5 (50 percent) means it has an equal chance of occurring or not occurring.

To demonstrate this with a monohybrid cross, consider the case of true-breeding pea plants with yellow versus green seeds. The dominant seed color is yellow; therefore, the parental genotypes were YY for the plants with yellow seeds and yy for the plants with green seeds. A Punnett square, devised by the British geneticist Reginald Punnett, is useful for determining probabilities because it is drawn to predict all possible outcomes of all possible random fertilization events and their expected frequencies. Figure 5 shows a Punnett square for a cross between a plant with yellow peas and one with green peas. To prepare a Punnett square, all possible combinations of the parental alleles (the genotypes of the gametes) are listed along the top (for one parent) and side (for the other parent) of a grid. The combinations of egg and sperm gametes are then made in the boxes in the table on the basis of which alleles are combining. Each box then represents the diploid genotype of a zygote, or fertilized egg. Because each possibility is equally likely, genotypic ratios can be determined from a Punnett square. If the pattern of inheritance (dominant and recessive) is known, the phenotypic ratios can be inferred as well. For a monohybrid cross of two true-breeding parents, each parent contributes one type of allele. In this case, only one genotype is possible in the F1 offspring. All offspring are Yy and have yellow seeds.

When the F1 offspring are crossed with each other, each has an equal probability of contributing either a Y or a y to the F2 offspring. The result is a 1 in 4 (25 percent) probability of both parents contributing a Y, resulting in an offspring with a yellow phenotype; a 25 percent probability of parent A contributing a Y and parent B a y, resulting in offspring with a yellow phenotype; a 25 percent probability of parent A contributing a y and parent B a Y, also resulting in a yellow phenotype; and a (25 percent) probability of both parents contributing a y, resulting in a green phenotype. When counting all four possible outcomes, there is a 3 in 4 probability of offspring having the yellow phenotype and a 1 in 4 probability of offspring having the green phenotype. This explains why the results of Mendel’s F2 generation occurred in a 3:1 phenotypic ratio. Using large numbers of crosses, Mendel was able to calculate probabilities, found that they fit the model of inheritance, and use these to predict the outcomes of other crosses.

Law of Segregation

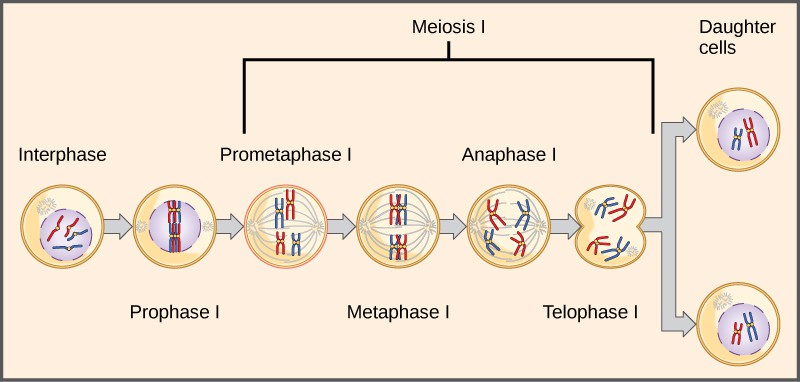

Observing that true-breeding pea plants with contrasting traits gave rise to F1 generations that all expressed the dominant trait and F2 generations that expressed the dominant and recessive traits in a 3:1 ratio, Mendel proposed the law of segregation. This law states that paired unit factors (genes) must segregate equally into gametes such that offspring have an equal likelihood of inheriting either factor. For the F2 generation of a monohybrid cross, the following three possible combinations of genotypes result: homozygous dominant, heterozygous, or homozygous recessive. Because heterozygotes could arise from two different pathways (receiving one dominant and one recessive allele from either parent), and because heterozygotes and homozygous dominant individuals are phenotypically identical, the law supports Mendel’s observed 3:1 phenotypic ratio. The equal segregation of alleles is the reason we can apply the Punnett square to accurately predict the offspring of parents with known genotypes. The physical basis of Mendel’s law of segregation is the first division of meiosis in which the homologous chromosomes with their different versions of each gene are segregated into daughter nuclei. This process was not understood by the scientific community during Mendel’s lifetime (Figure 3).

Test Cross

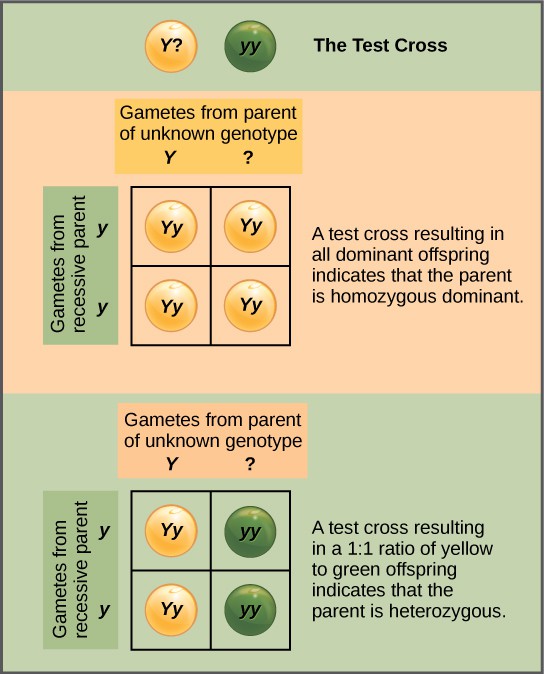

Beyond predicting the offspring of a cross between known homozygous or heterozygous parents, Mendel also developed a way to determine whether an organism that expressed a dominant trait was a heterozygote or a homozygote. Called the test cross, this technique is still used by plant and animal breeders. In a test cross, the dominant-expressing organism is crossed with an organism that is homozygous recessive for the same characteristic. If the dominant-expressing organism is a homozygote, then all F1 offspring will be heterozygotes expressing the dominant trait (Figure 4). Alternatively, if the dominant-expressing organism is a heterozygote, the F1 offspring will exhibit a 1:1 ratio of heterozygotes and recessive homozygotes (Figure 4). The test cross further validates Mendel’s postulate that pairs of unit factors segregate equally.

Lecture Video: Law of Segregation and Punnet squares

VISUAL CONNECTION

In pea plants, round peas (R) are dominant to wrinkled peas (r). You do a test cross between a pea plant with wrinkled peas (genotype rr) and a plant of unknown genotype that has round peas. You end up with three plants, all which have round peas.

From this data, can you tell if the parent plant is homozygous dominant or heterozygous?

Answer:

You cannot be sure if the plant is homozygous or heterozygous as the data set is too small: by random chance, all three plants might have acquired only the dominant gene even if the recessive one is present.

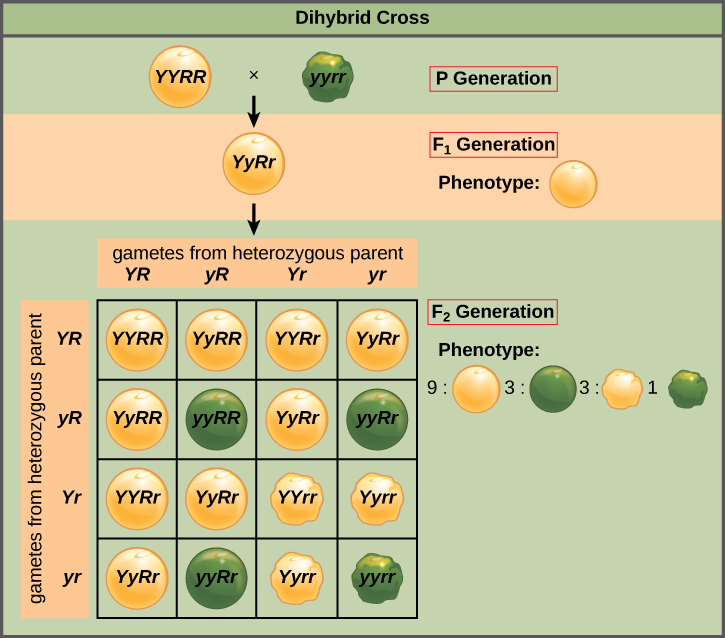

Law of Independent Assortment

Mendel’s law of independent assortment states that genes do not influence each other with regard to the sorting of alleles into gametes, and every possible combination of alleles for every gene is equally likely to occur. Independent assortment of genes can be illustrated by the dihybrid cross, a cross between two true-breeding parents that express different traits for two characteristics. Consider the characteristics of seed color and seed texture for two pea plants, one that has wrinkled, green seeds (rryy) and another that has round, yellow seeds (RRYY). Because each parent is homozygous, the law of segregation indicates that the gametes for the wrinkled–green plant all are ry, and the gametes for the round–yellow plant are all RY. Therefore, the F1 generation of offspring all are RrYy (Figure 6).

Lecture Video: Dihybrid Crosses and Law of Independent Assortment.

VISUAL CONNECTION

In pea plants, purple flowers (P) are dominant to white (p), and yellow peas (Y) are dominant to green (y).

- What are the possible genotypes and phenotypes for a cross between PpYY and ppYy pea plants?

- How many squares would you need to complete a Punnett square analysis of this cross?

Answers:

1. The possible genotypes are PpYY, PpYy, ppYY, and ppYy. The former two genotypes would result in plants with purple flowers and yellow peas, while the latter two genotypes would result in plants with white flowers with yellow peas, for a 1:1 ratio of each phenotype.

2. You only need a 2 × 2 Punnett square (four squares total) to do this analysis because two of the alleles are homozygous.

The gametes produced by the F1 individuals must have one allele from each of the two genes. For example, a gamete could get an R allele for the seed shape gene and either a Y or a y allele for the seed color gene. It cannot get both an R and an r allele; each gamete can have only one allele per gene. The law of independent assortment states that a gamete into which an r allele is sorted would be equally likely to contain either a Y or a y allele. Thus, there are four equally likely gametes that can be formed when the RrYy heterozygote is self-crossed, as follows: RY, rY, Ry, and ry. Arranging these gametes along the top and left of a 4 × 4 Punnett square (Figure 6) gives us 16 equally likely genotypic combinations. From these genotypes, we find a phenotypic ratio of 9 round–yellow:3 round–green:3 wrinkled–yellow:1 wrinkled–green (Figure 6). These are the offspring ratios we would expect, assuming we performed the crosses with a large enough sample size.

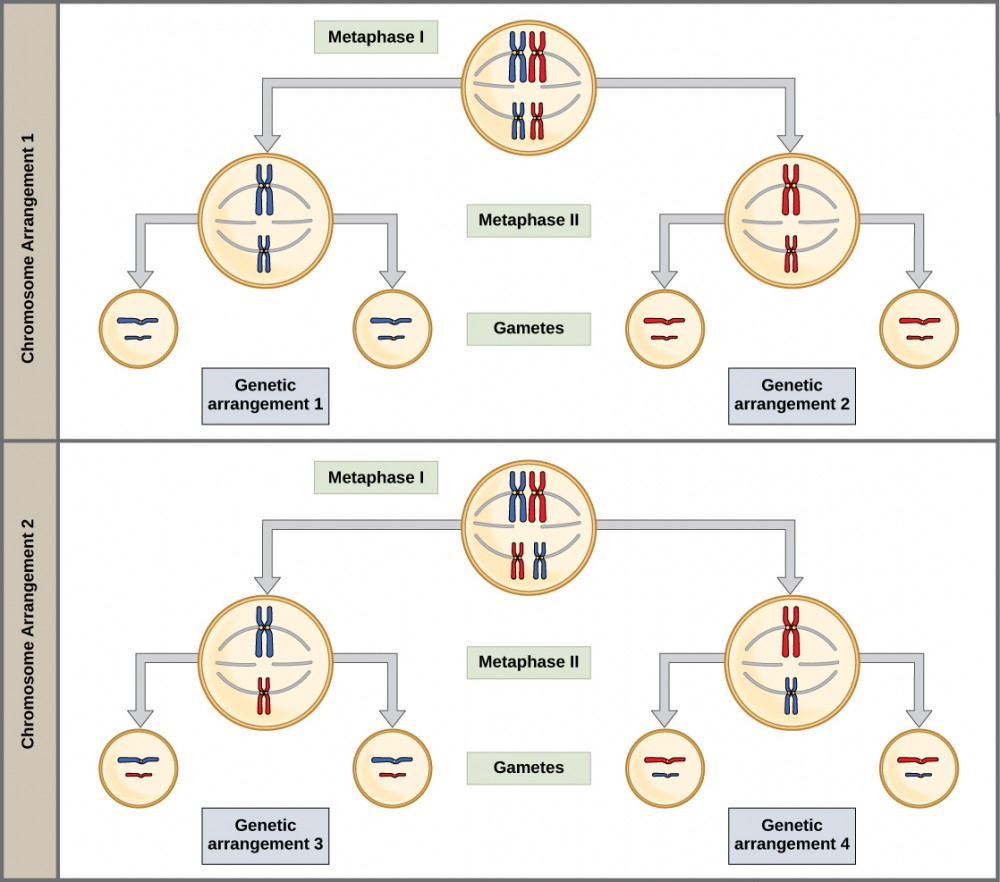

The physical basis for the law of independent assortment also lies in meiosis I, in which the different homologous pairs line up in random orientations. Each gamete can contain any combination of paternal and maternal chromosomes (and therefore the genes on them) because the orientation of tetrads on the metaphase plane is random (Figure 7).

Lecture Video: Independent Assortment and random fertilization.

Extensions of the Laws of Inheritance

Mendel studied traits with only one mode of inheritance in pea plants. The inheritance of the traits he studied all followed the relatively simple pattern of dominant and recessive alleles for a single characteristic. There are several important modes of inheritance, discovered after Mendel’s work, that do not follow the dominant and recessive, single-gene model.

Alternatives to Dominance and Recessiveness

Mendel’s experiments with pea plants suggested that: 1) two types of “units” or alleles exist for every gene; 2) alleles maintain their integrity in each generation (no blending); and 3) in the presence of the dominant allele, the recessive allele is hidden, with no contribution to the phenotype. Therefore, recessive alleles can be “carried” and not expressed by individuals. Such heterozygous individuals are sometimes referred to as “carriers.” Since then, genetic studies in other organisms have shown that much more complexity exists, but that the fundamental principles of Mendelian genetics still hold true. In the sections to follow, we consider some of the extensions of Mendelism.

Incomplete Dominance

Mendel’s results, demonstrating that traits are inherited as dominant and recessive pairs, contradicted the view at that time that offspring exhibited a blend of their parents’ traits. However, the heterozygote phenotype occasionally does appear to be intermediate between the two parents. For example, in the snapdragon, Antirrhinum majus (Figure 8), a cross between a homozygous parent with white flowers (CWCW) and a homozygous parent with red flowers (CRCR) will produce offspring with pink flowers (CRCW). (Note that different genotypic abbreviations are used for Mendelian extensions to distinguish these patterns from simple dominance and recessiveness.) This pattern of inheritance is described as incomplete dominance, meaning that one of the alleles appears in the phenotype in the heterozygote, but not to the exclusion of the other, which can also be seen. The allele for red flowers is incompletely dominant over the allele for white flowers. However, the results of a heterozygote self-cross can still be predicted, just as with Mendelian dominant and recessive crosses. In this case, the genotypic ratio would be 1 CRCR:2 CRCW:1 CWCW, and the phenotypic ratio would be 1:2:1 for red:pink:white. The basis for the intermediate color in the heterozygote is simply that the pigment produced by the red allele (anthocyanin) is diluted in the heterozygote and therefore appears pink because of the white background of the flower petals.

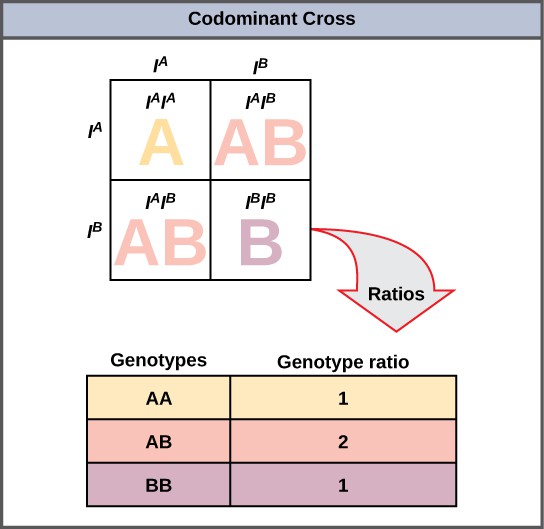

Codominance

A variation on incomplete dominance is codominance, in which both alleles for the same characteristic are simultaneously expressed in the heterozygote. An example of codominance occurs in the ABO blood groups of humans. The A and B alleles are expressed in the form of A or B molecules present on the surface of red blood cells. Homozygotes (IAIA and IBIB) express either the A or the B phenotype, and heterozygotes (IAIB) express both phenotypes equally. The IAIB individual has blood type AB. In a self-cross between heterozygotes expressing a codominant trait, the three possible offspring genotypes are phenotypically distinct. However, the 1:2:1 genotypic ratio characteristic of a Mendelian monohybrid cross still applies (Figure 9).

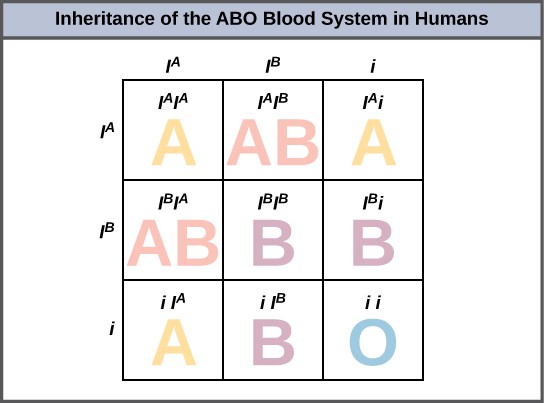

Multiple Alleles

Mendel implied that only two alleles, one dominant and one recessive, could exist for a given gene. We now know that this is an oversimplification. Although individual humans (and all diploid organisms) can only have two alleles for a given gene, multiple alleles may exist at the population level, such that many combinations of two alleles are observed. Note that when many alleles exist for the same gene, the convention is to denote the most common phenotype or genotype in the natural population as the wild type (often abbreviated “+”). All other phenotypes or genotypes are considered variants (mutants) of this typical form, meaning they deviate from the wild type. The variant may be recessive or dominant to the wild-type allele.

An example of multiple alleles is the ABO blood-type system in humans. In this case, there are three alleles circulating in the population. The IA allele codes for A molecules on the red blood cells, the IB allele codes for B molecules on the surface of red blood cells, and the i allele codes for no molecules on the red blood cells. In this case, the IA and IB alleles are codominant with each other and are both dominant over the i allele. Although there are three alleles present in a population, each individual only gets two of the alleles from their parents. This produces the genotypes and phenotypes shown in Figure 10. Notice that instead of three genotypes, there are six different genotypes when there are three alleles. The number of possible phenotypes depends on the dominance relationships between the three alleles.

EVOLUTION CONNECTION

Multiple Alleles Confer Drug Resistance in the Malaria Parasite

Malaria is a parasitic disease in humans that is transmitted by infected female mosquitoes, including Anopheles gambiae, and is characterized by cyclic high fevers, chills, flu-like symptoms, and severe anemia. Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax are the most common causative agents of malaria, and P. falciparum is the most deadly. When promptly and correctly treated, P. falciparum malaria has a mortality rate of 0.1 percent. However, in some parts of the world, the parasite has evolved resistance to commonly used malaria treatments, so the most effective malarial treatments can vary by geographic region.

In Southeast Asia, Africa, and South America, P. falciparum has developed resistance to the anti-malarial drugs chloroquine, mefloquine, and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine. P. falciparum, which is haploid during the life stage in which it is infective to humans, has evolved multiple drug-resistant mutant alleles of the dhps gene. Varying degrees of sulfadoxine resistance are associated with each of these alleles. Being haploid, P. falciparum needs only one drug-resistant allele to express this trait.

In Southeast Asia, different sulfadoxine-resistant alleles of the dhps gene are localized to different geographic regions. This is a common evolutionary phenomenon that comes about because drug-resistant mutants arise in a population and interbreed with other P. falciparum isolates in close proximity. Sulfadoxine-resistant parasites cause considerable human hardship in regions in which this drug is widely used as an over-the-counter malaria remedy. As is common with pathogens that multiply to large numbers within an infection cycle, P. falciparum evolves relatively rapidly (over a decade or so) in response to the selective pressure of commonly used anti-malarial drugs. For this reason, scientists must constantly work to develop new drugs or drug combinations to combat the worldwide malaria burden.1

X-linked Traits

In humans, as well as in many other animals and some plants, the sex of the individual is determined by sex chromosomes—one pair of non-homologous chromosomes. Until now, we have only considered inheritance patterns among non-sex chromosomes, or autosomes. In addition to 22 homologous pairs of autosomes, human females have a homologous pair of X chromosomes, whereas human males have an XY chromosome pair. Although the Y chromosome contains a small region of similarity to the X chromosome so that they can pair during meiosis, the Y chromosome is much shorter and contains fewer genes. When a gene being examined is present on the X, but not the Y, chromosome, it is X-linked.

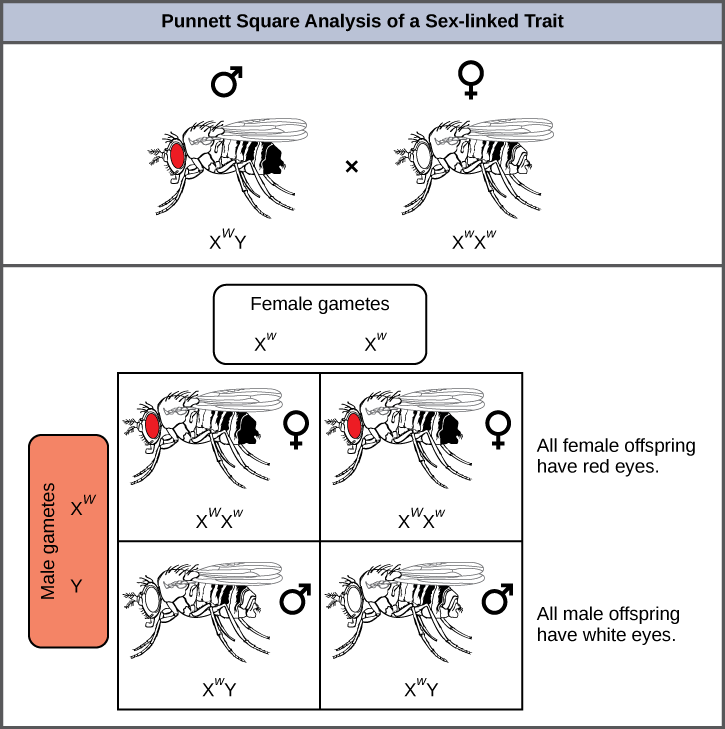

Eye color in Drosophila, the common fruit fly, was the first X-linked trait to be identified. Thomas Hunt Morgan mapped this trait to the X chromosome in 1910. Like humans, Drosophila males have an XY chromosome pair, and females are XX. In flies, the wild-type eye color is red (XW) and is dominant to white eye color (Xw) (Figure 11). Because of the location of the eye-color gene, reciprocal crosses do not produce the same offspring ratios. Males are said to be hemizygous, in that they have only one allele for any X-linked characteristic. Hemizygosity makes descriptions of dominance and recessiveness irrelevant for XY males. Drosophila males lack the white gene on the Y chromosome; that is, their genotype can only be XWY or XwY. In contrast, females have two allele copies of this gene and can be XWXW, XWXw, or XwXw.

In an X-linked cross, the genotypes of F1 and F2 offspring depend on whether the recessive trait was expressed by the male or the female in the P generation. With respect to Drosophila eye color, when the P male expresses the white-eye phenotype and the female is homozygously red-eyed, all members of the F1 generation exhibit red eyes (Figure 12). The F1 females are heterozygous (XWXw), and the males are all XWY, having received their X chromosome from the homozygous dominant P female and their Y chromosome from the P male. A subsequent cross between the XWXw female and the XWY male would produce only red-eyed females (with XWXW or XWXw genotypes) and both red- and white-eyed males (with XWY or XwY genotypes). Now, consider a cross between a homozygous white-eyed female and a male with red eyes. The F1 generation would exhibit only heterozygous red-eyed females (XWXw) and only white-eyed males (XwY). Half of the F2 females would be red-eyed (XWXw) and half would be white-eyed (XwXw). Similarly, half of the F2 males would be red-eyed (XWY) and half would be white-eyed (XwY).

VISUAL CONNECTION

What ratio of offspring would result from a cross between a white-eyed male and a female that is heterozygous for red eye color?

Answer:

Half of the female offspring would be heterozygous (XWXw) with red eyes, and half would be homozygous recessive (XwXw) with white eyes. Half of the male offspring would be hemizygous dominant (XWY) with red eyes, and half would be hemizygous recessive (XwY) with white eyes.

Discoveries in fruit fly genetics can be applied to human genetics. When a female parent is homozygous for a recessive X-linked trait, she will pass the trait on to 100 percent of her male offspring, because the males will receive the Y chromosome from the male parent. In humans, the alleles for certain conditions (some color-blindness, hemophilia, and muscular dystrophy) are X-linked. Females who are heterozygous for these diseases are said to be carriers and may not exhibit any phenotypic effects. These females will pass the disease to half of their sons and will pass carrier status to half of their daughters; therefore, X-linked traits appear more frequently in males than females.

In some groups of organisms with sex chromosomes, the sex with the non-homologous sex chromosomes is the female rather than the male. This is the case for all birds. In this case, sex-linked traits will be more likely to appear in the female, in whom they are hemizygous.

Lecture Video: X-linked genes.

CONCEPTS IN ACTION: X-linked traits

The following videos provide additional review of the concept of x-linked genes and how they influence patterns of inheritance.

Pedigrees and genetic problem solving

Pedigrees provide a history of inheritance for a given trait in a family. Using the laws of inheritance, genetics can deduce genotypes for single-gene traits within a family based solely on phenotypes and use this information to make predictions about the phenotype of future generations.

- allele

- one of two or more variants of a gene that determines a particular trait for a characteristic

- carrier

- refers to an individual with a heterozygous genotype thus being a carrier of a genetic disease while not expressing it phenotypically

-

- codominance

- in a heterozygote, complete and simultaneous expression of both alleles for the same characteristic

dihybrid

the result of a cross between two true-breeding parents that express different traits for two characteristics

- genotype

- the underlying genetic makeup, consisting of both physically visible and non-expressed alleles, of an organism

- hemizygous

- the presence of only one allele for a characteristic, as in X-linkage; hemizygosity makes descriptions of dominance and recessiveness irrelevant

heterozygous

having two different alleles for a given gene on the homologous chromosomes

-

- homologous chromosomes

- a pair of chromosomes, one from the mother and one from the father

- homozygous

- having two identical alleles for a given gene on the homologous chromosomes

- incomplete dominance

- in a heterozygote, expression of two contrasting alleles such that the individual displays an intermediate phenotype

law of dominance

in a heterozygote, one trait will conceal the presence of another trait for the same characteristic

- law of independent assortment

- genes do not influence each other with regard to sorting of alleles into gametes; every possible combination of alleles is equally likely to occur

- law of segregation

- paired unit factors (i.e., genes) segregate equally into gametes such that offspring have an equal likelihood of inheriting any combination of factors

- monohybrid

- the result of a cross between two true-breeding parents that express different traits for only one characteristic

- phenotype

- the observable traits expressed by an organism

- Punnett square

- a visual representation of a cross between two individuals in which the gametes of each individual are denoted along the top and side of a grid, respectively, and the possible zygotic genotypes are recombined at each box in the grid

- sex chromosomes

- sex chromosomes are a pair of non-homologous chromosomes which determine the sex of the organism; in humans the sex chromosomes are X and Y

test cross

a cross between a dominant expressing individual with an unknown genotype and a homozygous recessive individual; the offspring phenotypes indicate whether the unknown parent is heterozygous or homozygous for the dominant trait

- tetrad

- a tetrad is a structure that forms during Meosis, comprised of a pair of homologous chromosomes (4 chomatids)

-

- X-linked (Sex-linked)

- a gene present on the X chromosome, but not the Y chromosome

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/concepts-biology/pages/1-introduction