7 Chapter 7: Health and Environmental Justice

Introduction

One lazy Sunday morning, you are doing some channel surfing. While looking for your favorite cartoon show, you happen to stumble upon your local news channel. There appears to be a heated debate between the two pundits on the screen.

“Climate change is a fact of life. Your ignorance will cause the global economy billions, if not trillions, of dollars in the coming decades. People all over the world are starting to feel the effects of mankind’s manipulation of the environment. Addressing climate change is about providing justice for people all over the planet” exclaimed one pundit.

“Scientists have proven that the earth’s many climates have varied naturally over the millennia. The South Pole used to be a tropical rainforest, for crying out loud. There is no evidence that the current variations in climate are caused by people. Climate change is nothing more than doomsday propaganda. There is no justice in throwing away billions of dollars investing in climate change research and prevention.” responded the other pundit.

You wonder what these two news reporters are so angry about. What are they talking about? What is climate change? Is the environment a source of injustice? What is environmental justice, then? The goal of this chapter is to provide you, the reader, information about environmental inequalities so you can answer that question for yourself. Specifically, this chapter will focus on the environmental inequalities caused by climate change. Moreover, this chapter will argue that the effects of climate change disproportionately affect people of color at a micro level and countries with low socioeconomic status at a macro level due to environmental injustice.

Health and Environmental Justice, Health Inequities, and Environmental Injustice Defined

To begin, I will explain health and environmental justice by breaking down each word. Then, I will give you a simplified definition of what health and environmental justice is before explaining why it is important. First, in this context, the World Health Organization defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (“Constitution”, 2021). Physical, mental, and social well-being all intertwine. One can affect another and vice versa. Additionally, an individual’s environment can affect a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being. So, what is an environment in this context? The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences defines environment as “everything around you…Home…school…work…places that you visit…places where your food is grown or prepared…and even the places your drinking water travels through on its way to your home” (“Environmental Justice”, 2017). Everyone has many different environments that they spend time in and those environments vary. Some have more privileged environments than others which is why the word justice is important. Justice is defined as “fair treatment—fair treatment for everyone” (“Environmental Justice”, 2017). Health and environmental justice is also defined by The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences in 2017. Health and environmental justice is a “term that simply means making sure that everyone has a fair chance of living the healthiest life possible” (“Environmental Justice”, 2017). Now, the question is why is health and environmental justice important?

Health and environmental justice is important because there are health inequities and environmental injustice. Castiello, a researcher and nurse practitioner, defines health inequities as “differences in health between different groups of people” (Castiello, 2021). She says that “these widespread differences are the result of unfair systems that negatively affect people’s living conditions, access to healthcare, and overall health status” (Castiello, 2021). We need to be aware that justice is not a far fetched idea even though it may be difficult. There are unfair systems that need to be changed to improve people’s living conditions, access to healthcare, and overall health. Another term that shows us why health and environmental justice is important is environmental injustice. Maantay from the Department of Geology and Geography at Lehman College defines environmental injustice as “the disproportionate exposure of communities of color and the poor to pollution, and its concomitant effects on health and environment” (Maantay, 2002). Environmental injustice comes from “the unequal environmental protection and environmental quality provided through laws, regulations, governmental programs, enforcement, and policies” (Maantay, 2002).

Socioeconomic Status Defined

Terms like class and social standing commonly thrown around in today’s vernacular. For example, in the movie High School Musical the main character, Troy Bolton, frequently worries about what acting in the school play will do to his social standing at school. But, what do these terms mean sociologically? How is our position in society actually quantified and determined? One common metric to determine social standing is socioeconomic status. According to the American Psychological Association, socioeconomic status is, “the social standing or class of an individual or group. It is often measured as a combination of education, income and occupation” (American Psychological Association, n.d., para. 1). The APA also goes on to note that, “examinations of socioeconomic status often reveal inequities in access to resources, plus issues related to privilege, power, and control” (American Psychological Association, n.d., para. 2). So, one of the best ways to study the inequalities of climate change is to examine how individuals and groups with different socioeconomic statuses are impacted differently.

For more on socioeconomic status, visit section 8.3 in this OER textbook: https://www.oercommons.org/courses/sociology-understanding-and-changing-the-social-world/view

Climate Change Defined

With background concepts like race, socioeconomic status, and environmental justice defined, we can now move on to defining climate change and examining its impacts. The sociology textbook Introduction to Sociology 2e (2017) by Heather Griffiths defines climate change as a term used to describe long

term shifts in temperature and climate (Griffiths, p. 367). Moreover, according to NASA, climate change is the idea that releasing gases known as greenhouse gases into the atmosphere creates a warming effect on the planet, which will do permanent damage to longstanding weather patterns and environments around the world (Dunbar, 2015, para. 1). Greenhouse gases are gases that trap the Earth’s heat when released into the atmosphere, creating what is known as the greenhouse effect (Dunbar, 2015, para. 2). Greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxides, and fluorinated gases. These gases are released into the atmosphere in a number of ways. Energy production, transportation, agricultural practices, and other industrial activities all release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere (Dunbar, 2015, para 5). Greenhouse gases work by trapping Earth’s heat. Solar energy absorbed at Earth’s surface is radiated back into the atmosphere as heat. As the heat makes its way through the atmosphere and back out to space, greenhouse gases absorb much of it (Dunbar, 2015, para. 7). As a result, much of the heat the Earth gives off is kept near the Earth’s surface. The result of excess heat being kept near Earth’s surface is that climates drastically change all over the planet. For example, the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases has led to a steady increase in temperatures at the poles.

For a more in-depth history of climate change and the subsequent global response, visit the introduction of this OER textbook: https://www.oercommons.org/courses/negotiating-climate-change-in-crisis.

For a better understanding of the impacts climate change has on the environment, specifically, the American environment, please visit this OER textbook: http://www.oercommons.org/courses/2014-national-climate-assessment/view.

Race Defined

The issue of race is something that has become especially prevalent in our world today. There have been many movements that have arisen that pertain to race. These movements usually pertain to how different races are treated in our country and the social injustices that people of color face. Although it has become especially prevalent in our world today, it is still very much a controversial issue. You may hear various opinions from various peoples, but perhaps it is worth asking: what is race? Is it something that pertains exclusively to one’s skin color? Is it biological? According to Bergman and Luckmann: “Race is a social construct, a construct that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is”(Bergman and Luckmann 1966). Race is a social construct that was created to perpetuate inequalities between groups of people. Although race may have its genesis in the minds of human beings, it has had detrimental effects for countless people around the world.

A Brief History of Health and Environmental Justice

Protests in Warren County, North Carolina are believed to launch the environmental justice movement (Mohai et al., 2009). The protests raised public awareness of how African Americans and other people of color had major environmental concerns (Mohai et al., 2009). The national media attention that the protests drummed up led to the U.S. General Accounting Office investigating how race correlated to what communities were near hazardous waste landfills in the South (Mohai et al., 2009). A report entitled Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States from the year 1987 published the study’s results (Mohai et al., 2009). Following suit, sociologists and other scholars started diving into the concept of environmental justice, particularly looking at how people of color and low income individuals are impacted (Mohai et al., 2009).  Eventually, the Office of Environmental Justice was created and the U.S. Congress was compelled to begin holding hearings on environmental justice (Mohai et al., 2009). To learn more about this history, how exposures to pollution and other environmental risks are unequally distributed by race and class, and the emerging issue of global climate justice, Paul Mohai, David Pellow, and J. Timmons Roberts discusses these topics in their Annual Review of Environment and Resources from 2009.

Eventually, the Office of Environmental Justice was created and the U.S. Congress was compelled to begin holding hearings on environmental justice (Mohai et al., 2009). To learn more about this history, how exposures to pollution and other environmental risks are unequally distributed by race and class, and the emerging issue of global climate justice, Paul Mohai, David Pellow, and J. Timmons Roberts discusses these topics in their Annual Review of Environment and Resources from 2009.

Two Main Viewpoints on Climate Change

There are two commonly held beliefs about climate change. One side is populated by individuals who believe that climate change is an immediate threat to not only our planet, but also our very existence. These individuals advocate for immediate actions and policies in an attempt to slow the detrimental effects of our changing planet. The opposing side is populated by individuals who do not believe that climate change exists, or believe that it is not an immediate issue that warrants immediate action. These reasons vary from: misinformation, lack of knowledge, outright denialism of evidence, ect. An individual’s sense of identities can shape how they perceive climate change.

Identities that Impact Perceptions of Climate Change

There are approximately 7,800,000,000 people in the world and climate change affects us all in one way or another. However, an individual’s perception of climate change depends on their experiences and identities. So, I would like to point out how a few specific identities can impact an individual’s perceptions of climate change. The three main identities that I will discuss are race, ethnicity, and political orientation.

A national survey experiment by Schuldt and Pearson surveyed 2,041 adults from the United States to explore these three identities in regards to climate change opinion. They found some interesting results. First, “non-whites’ views were less politically polarized than those of whites and were unaffected by exposure to different ways of framing the issue” (Schuldt & Pearson, 2016). To further explain the experiment and make an important point, the way an issue is framed or described to individuals in a discussion, survey, interview, etc. may impact how those individuals react or respond. In this survey, the conductors of the survey used both “global warming” and “climate change”. Second, “non-whites were reliably less likely to self-identify as environmentalists compared to Whites, despite expressing existence beliefs and support for regulating greenhouse gases at levels comparable to Whites” (Schuldt & Pearson, 2016).  These two findings suggest that we need to take a closer look at the way racial and ethnic identities shape a person’s core beliefs about climate change and how those beliefs impact their actions. There is one main reason these findings are important to point out. We can improve current public outreach and climate science advocacy. Once we understand how certain races and ethnicities respond to framing the issue as global warming or climate change, we can change how we approach and frame the issue with certain communities. And second, once we understand which races and ethnicities are more likely to call themselves environmentalists, we can reflect on current outreach approaches with different communities and keep improving them to increase the number of environmental advocates.

These two findings suggest that we need to take a closer look at the way racial and ethnic identities shape a person’s core beliefs about climate change and how those beliefs impact their actions. There is one main reason these findings are important to point out. We can improve current public outreach and climate science advocacy. Once we understand how certain races and ethnicities respond to framing the issue as global warming or climate change, we can change how we approach and frame the issue with certain communities. And second, once we understand which races and ethnicities are more likely to call themselves environmentalists, we can reflect on current outreach approaches with different communities and keep improving them to increase the number of environmental advocates.

And finally, I just discussed the identities of race and ethnicity. Political orientation is also important when it comes to outreach and climate science advocacy. Someone with a conservative political orientation is more likely to deny climate change exists, refute the scientific data that suggests climate change is real, and oppose policies aimed at reducing climate change (Funk & Hefferon, 2019). Someone with a liberal political orientation is more likely to accept climate change as real, believe current scientific data suggesting climate change is real, and support policies aimed at reducing climate change (Funk & Hefferon, 2019). Understanding the political orientation of an individual can help climate science advocates decide who to reach out to when looking for support and who may need more convincing on the issue.

The Global North-South Divide and Climate Change

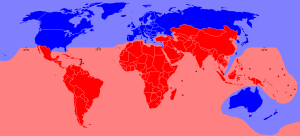

Not only do individual identities impact perception and experiences with climate change, national identities also impact experiences with climate change. How a country is identified socioeconomically, for example, can undoubtedly shape their experiences with climate change. Countries are typically lumped into one of two groups when being identified socioeconomically. Those two groups being the Global North and the Global South. The Global North consists of the blue countries on the map. According to the article A Comparative Analysis of Global North and Global South Economies by Lemuel Odeh, these countries have highly developed and industrialized economies (Odeh, n.d., p. 12). As a result, Global North countries have stable economies, which leads to a greater standard of living for people within that country (Odeh, n.d., pp. 14-15). For example, when compared to Global South countries,

Global North countries typically have lower unemployment rates, better infrastructure, better healthcare, greater political stability, etc. The Global South consists of the red countries on the map. According to Odeh, unlike the Global North, these countries are less economically developed (Odeh, n.d., p. 18). As mentioned, this economic underdevelopment has resulted in social instability. Global South countries lag behind their Global North counterparts when it comes to infrastructure, healthcare, unemployment, and several other social factors.

Now that the Global North-South Divide has been defined, the question that needs to be asked is this: How does the Global North-South divide relate to climate change? The socioeconomic differences between the Global North and the Global South has resulted in different experiences when it comes to climate change. For example, the economic stability of the Global North has allowed for these countries to begin to transition away from fossil fuels and dirty energy (Odeh, n.d., p. 27). To clarify, Global North countries are so wealthy that they are beginning to come up with new methods of transportation and energy production that no longer release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The same cannot be said for Global South countries. The underdevelopment of their economies has made Global South countries almost entirely dependent on fossil fuels, which release greenhouse gases when utilized for energy or transportation (Odeh, n.d., p. 28). According to sociologist Kari Norgaard, Global North and Global South countries are also impacted by climate change differently. As a result of underdevelopment, the Global South is disproportionately affected by climate change. For example, the islands in the Global South lack the infrastructure to effectively handle the rising ocean levels caused by climate change (Norgaard, 2012, p. 87). Global South countries also lack the infrastructure and healthcare to handle natural disasters caused by climate change (Norgaard, 2012, p. 83). Climate change also causes an increase in famine and disease, which are more damaging in the unstable Global South (Norgaard, 2012, p. 93).

For more information on how countries are classified and studied socioeconomically, please visit chapter 10 of this OER textbook: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/10-1-global-stratification-and-classification.

For more information on how climate change impacts groups and individuals within both the Global North and South, please visit this OER: https://www.oercommons.org/courses/an-introduction-to-global-health-climate-change-and-health-18-01-2.

Race and Climate Change

Climate change is an issue that affects every single human being that lives on this planet. To what degree it affects certain people is dependent on certain factors such as socioeconomic status, and location just to name a few. Although climate change affects humans at every level, something that is alarming is how disproportionately people of color are affected by climate change compared to their caucasian counterparts. Specifically, we will be examining two particular vulnerable groups of people. Children, and the incarcerated.

Children of Color and Health Care

The practice of redlining is no longer utilized, but it’s effects are still felt today. Redlining was the practice of determining how desirable areas were for investment. Racial makeup heavily influenced desirability. White neighborhoods were deemed more desirable for investment than non-white neighborhoods. 71% of historically redlined areas are low-to-middle income areas and 64% are minority areas(black & hispanic. The practice of redlining can be seen in one of the most prominent cities in the southern region of the United States. “An overhead image of the city of Atlanta, Georgia reveals the dominance of heat-absorbing impervious surfaces(e.g concrete and asphalt), consequently, residents of these neighborhoods(still mostly black) are exposed to more vehicular exhaust as well as higher surface temperatures from structures that absorb and radiate heat during the hottest days”(Gutschow et al). Factors such as these can put these communities in danger of heat-related illnesses, as well as other adverse health effects, with children being particularly vulnerable. Some of these adverse health effects include: In the US, a black child has nearly twice the risk of developing asthma, 2-3 times the rate of emergency visits and hospitalization from asthma, and almost 5 times the mortality rate from asthma than their caucasian counterparts. Not only are children of color more likely to experience heat-related illnesses, but are also more likely to face floods and blackouts that arise from climate change. These sudden events can have adverse mental and psychological effects on children. Which can result in behavioral concerns. There is a significant association between heat exposure, air pollution and preterm birth and low birth weight, with black mothers at highest risk. Climate change disproportionately affects children of color, even while they have yet to be born.

Inmates and climate change

“Inmates are among the most vulnerable populations on our warming planet -and among the most ignored”(Levision 2021). The incarcerated are particular vulnerable due to several factors. Poor ventilation in prisons has caused instances of overheating in these institutions, which has increased the likelihood that inmates suffer heat-related illnesses, and this is something that has even affected prison guards(Levision). Another major concern is the issue of relocation. Flooding is an adverse weather event that has increased in frequency and when flooding occurs, inmates have to be relocated to safer locations. This is something that is not always possible to due time and budget constraints, and due to these limitations, there have been several instances where inmates were left behind in unclean neck-high flood water(Levision). Not only are the incarcerated particularly vulnerable due to their positions and place in our society, but this also disproportionately affects people of color as black and latinos are incarcerated at a higher rate than their caucasian counterparts(Levision). Climate change has and will continue to exacerbate the systemic injustices faced by people of color.

Scope of Limitation

We feel it is important to mention that there are limitations to our research. There are an abundance of topics and individuals that we could discuss in regards to the area of health and environmental justice as a whole. But due to the many resources on health and environmental justice and the limited amount of time that we have, we simply are not able to research, write, and present as much information as we would like to. For the sake of being concise, we focused on how climate change and the identities of race and socioeconomic status intersect. Not to mention, we are not experts on this subject and as a group we have had very little background on health and environmental justice before starting this project.

Call to Action

All in all, climate change is a real threat especially to marginalized populations such as people of color and the poor. We are calling on you to help reflect on and change unequal systems and protections. So, be curious and dive into research about climate change. Be empathetic of the challenges that marginalized populations have to face. Question current environmental protections and challenge societal institutions that perpetuate environmental injustices.

References

10.1 global stratification and classification – introduction to sociology 2E. OpenStax. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/10-1-global-stratification-and-classification.

2014 national climate assessment | OER commons. (n.d.). Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.oercommons.org/courses/2014-national-climate-assessment.

A Comparative Analysis of Global North and Global South Economies. (n.d.). ResearchGate. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265425871_A_comparative_analysis_of_global_north_and_global_south_economies.

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Socioeconomic status. American Psychological Association. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/topics/socioeconomic-status.

Castiello, L. (2021). What is health inequity? Medical News Today. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/health-inequity.

“Constitution”. (2021). World Health Organization. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from

https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution.

Dunbar, B. (2015, May 13). What is climate change? NASA. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/k-4/stories/nasa-knows/what-is-climate-change-k4.html.

“Environmental Justice”. (2017). National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://kids.niehs.nih.gov/topics/environment-health/environmental-justice/index.htm.

Funk, C. & Hefferon, M. (2019). U.S. Public Views on Climate and Energy. Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 29, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2019/11/25/u-s-public-views-on-climate-and-energy/.

Furu, P. (n.d.). An Introduction to Global Health. Oer Commons. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.oercommons.org/kaltura/embed/1_4faxn69m.

Griffiths, H., Keirns, N. J., Strayer, E., Cody-Rydzewski, S., Scaramuzzo, G., Sadler, T., Vyain, S., Bry, J., & Jones, F. (2017). Introduction to sociology 2E. OpenStax College, Rice University.

Gutschow, B., Gray, B., Ragavan, M. I., Sheffield, P. E., Philipsborn, R. P., & Jee, S. H. (2021, July 5)

Levenson, L. L. (2021). CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM. Environmental Law, 51(2), 333–381. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27027144

Maantay, J. (2002). Mapping Environmental Injustices: Pitfalls and Potential of Geographic Information Systems in Assessing Environmental Health and Equity. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(2), 161-171. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/pdf/10.1289/ehp.02110s2161.

Mohai, P., Pellow, D., & Roberts, J. T. (2009). Environmental justice. Annual review of environment and resources, 34, 405-430.

Norgaard, K. M. (2012). CLIMATE DENIAL AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF INNOCENCE: REPRODUCING TRANSNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL PRIVILEGE IN THE FACE OF CLIMATE CHANGE. Race, Gender & Class, 19(1), 80-103.

Schuldt, J., & Pearson, A. (2016). The role of race and ethnicity in climate change polarization: evidence from a U.S. national survey experiment. Climatic Change, 136(3/4), 495–505. https://doi-org.ezproxy.morris.umn.edu/10.1007/s10584-016-1631-3.

Sullivan, S., & Bohm, S. (n.d.). Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.oercommons.org/courses/negotiating-climate-change-in-crisis.

University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2010 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. (2016, April 8). Sociology. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://open.lib.umn.edu/sociology/