4 Chapter 4: Economics and Classism

Introduction to Economics

Throughout history, there has been a social structure that is vital in building civilization, producing advanced technologies, and developing international social relationships. The intercultural relationship is completely interwoven with the economic process, and its implementation has made the interpersonal relationships between people even more essential in the progression of humanity. Economies have been the primary method of producing goods and services, distributing them, and subsequently consuming them.

The following section is from: (Introduction to Sociology 2e)

Our earliest ancestors lived as hunter-gatherers. Small groups of extended families roamed from place to place looking for subsistence. They would settle in an area for a brief time when there were abundant resources. They hunted animals for their meat and gathered wild fruits, vegetables, and cereals. They ate what they caught or gathered their goods as soon as possible, because they had no way of preserving or transporting it. Once the resources of an area ran low, the group had to move on, and everything they owned had to travel with them. Food reserves only consisted of what they could carry. Many sociologists contend that hunter-gatherers did not have a true economy, because groups did not typically trade with other groups due to the scarcity of goods.

The Agricultural Revolution

The first true economies arrived when people started raising crops and domesticating animals. Although there is still a great deal of disagreement among archeologists as to the exact timeline, research indicates that agriculture began independently and at different times in several places around the world. The earliest agriculture was in the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East around 11,000–10,000 years ago. Next were the valleys of the Indus, Yangtze, and Yellow rivers in India and China, between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago. The people living in the highlands of New Guinea developed agriculture between 9,000 and 6,000 years ago, while people were farming in Sub-Saharan Africa between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago. Agriculture developed later in the western hemisphere, arising in what would become the eastern United States, central Mexico, and northern South America between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago (Diamond 2003).

Figure 1.1 Agricultural practices have emerged in different societies at different times. (Information courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Agriculture began with the simplest of technologies—for example, a pointed stick to break up the soil—but really took off when people harnessed animals to pull an even more efficient tool for the same task: a plow. With this new technology, one family could grow enough crops not only to feed themselves but also to feed others. Knowing there would be abundant food each year as long as crops were tended led people to abandon the nomadic life of hunter-gatherers and settle down to farm.

The improved efficiency in food production meant that not everyone had to toil all day in the fields. As agriculture grew, new jobs emerged, along with new technologies. Excess crops needed to be stored, processed, protected, and transported. Farming equipment and irrigation systems needed to be built and maintained. Wild animals needed to be domesticated and herds shepherded. Economies began to develop because people now had goods and services to trade. At the same time, farmers eventually came to labor for the ruling class.

As more people specialized in non-farming jobs, villages grew into towns and then into cities. Urban areas created the need for administrators and public servants. Disputes over ownership, payments, debts, compensation for damages, and the like led to the need for laws and courts—and the judges, clerks, lawyers, and police who administered and enforced those laws.

At first, most goods and services were traded as gifts or through bartering between small social groups (Mauss 1922). Exchanging one form of goods or services for another was known as bartering. This system only works when one person happens to have something the other person needs at the same time. To solve this problem, people developed the idea of a means of exchange that could be used at any time: that is, money. Money refers to an object that a society agrees to assign a value to so it can be exchanged for payment. In early economies, money was often objects like cowry shells, rice, barley, or even rum. Precious metals quickly became the preferred means of exchange in many cultures because of their durability and portability. The first coins were minted in Lydia in what is now Turkey around 650–600 B.C.E. (Goldsborough 2010). Early legal codes established the value of money and the rates of exchange for various commodities. They also established the rules for inheritance, fines as penalties for crimes, and how property was to be divided and taxed (Horne 1915). A symbolic interactionist would note that bartering and money are systems of symbolic exchange. Monetary objects took on a symbolic meaning, one that carries into our modern-day use of cash, checks, and debit cards.

As city-states grew into countries and countries grew into empires, their economies grew as well. When large empires broke up, their economies broke up too. The governments of newly formed nations sought to protect and increase their markets. They financed voyages of discovery to find new markets and resources all over the world, which ushered in a rapid progression of economic development.

Colonies were established to secure these markets, and wars were financed to take over territory. These ventures were funded in part by raising capital from investors who were paid back from the goods obtained. Governments and private citizens also set up large trading companies that financed their enterprises around the world by selling stocks and bonds.

Governments tried to protect their share of the markets by developing a system called mercantilism. Mercantilism is an economic policy based on accumulating silver and gold by controlling colonial and foreign markets through taxes and other charges. The resulting restrictive practices and exacting demands included monopolies, bans on certain goods, high tariffs, and exclusivity requirements. Mercantilistic governments also promoted manufacturing and, with the ability to fund technological improvements, they helped create the equipment that led to the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution

Until the end of the eighteenth century, most manufacturing was done by manual labor. This changed as inventors devised machines to manufacture goods. A small number of innovations led to a large number of changes in the British economy. In the textile industries, the spinning of cotton, worsted yarn, and flax could be done more quickly and less expensively using new machines with names like the Spinning Jenny and the Spinning Mule (Bond 2003). Another important innovation was made in the production of iron: Coke from coal could now be used in all stages of smelting rather than charcoal from wood, which dramatically lowered the cost of iron production while increasing availability (Bond 2003). James Watt ushered in what many scholars recognize as the greatest change, revolutionizing transportation and thereby the entire production of goods with his improved steam engine.

As people moved to cities to fill factory jobs, factory production also changed. Workers did their jobs in assembly lines and were trained to complete only one or two steps in the manufacturing process. These advances meant that more finished goods could be manufactured with more efficiency and speed than ever before.

The Industrial Revolution also changed agricultural practices. Until that time, many people practiced subsistence farming in which they produced only enough to feed themselves and pay their taxes. New technology introduced gasoline-powered farm tools such as tractors, seed drills, threshers, and combine harvesters. Farmers were encouraged to plant large fields of a single crop to maximize profits. With improved transportation and the invention of refrigeration, produce could be shipped safely all over the world.

The Industrial Revolution modernized the world. With growing resources came growing societies and economies. Between 1800 and 2000, the world’s population grew sixfold, while per capita income saw a tenfold jump (Maddison 2003).

While many people’s lives were improving, the Industrial Revolution also birthed many societal problems. There were inequalities in the system. Owners amassed vast fortunes while laborers, including young children, toiled for long hours in unsafe conditions. Workers’ rights, wage protection, and safe work environments are issues that arose during this period and remain concerns today.

Postindustrial Societies and the Information Age

Postindustrial societies, also known as information societies, have evolved in modernized nations. One of the most valuable goods of the modern era is information. Those who have the means to produce, store, and disseminate information are leaders in this type of society.

One way scholars understand the development of different types of societies (like agricultural, industrial, and postindustrial) is by examining their economies in terms of four sectors: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. Each has a different focus. The primary sector extracts and produces raw materials (like metals and crops). The secondary sector turns those raw materials into finished goods. The tertiary sector provides services: child care, healthcare, and money management. Finally, the quaternary sector produces ideas; these include the research that leads to new technologies, the management of information, and a society’s highest levels of education and the arts (Kenessey 1987).

In underdeveloped countries, the majority of the people work in the primary sector. As economies develop, more and more people are employed in the secondary sector. In well-developed economies, such as those in the United States, Japan, and Western Europe, the majority of the workforce is employed in service industries. In the United States, for example, almost 80 percent of the workforce is employed in the tertiary sector (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2011).

The rapid increase in computer use in all aspects of daily life is a main reason for the transition to an information economy. Fewer people are needed to work in factories because computerized robots now handle many of the tasks. Other manufacturing jobs have been outsourced to less-developed countries as a result of the developing global economy. The growth of the Internet has created industries that exist almost entirely online. Within industries, technology continues to change how goods are produced. For instance, the music and film industries used to produce physical products like CDs and DVDs for distribution. Now those goods are increasingly produced digitally and streamed or downloaded at a much lower physical manufacturing cost. Information and the means to use it creatively have become commodities in a postindustrial economy.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY, OpenStax, Introduction to Sociology 2e. Provided by: Rice University. Download for free at https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8423. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

As humans have evolved their socioeconomic system for communicating and producing, two main types of economic systems have been pushed to the forefront of our society. One type of system that is commonplace in many nations is a market economy, which is an economy that is capitalist and is in most cases purely controlled by the market with little influence from the government. The other type of economy is an interventionist economy, which has much more government regulation and very little, if any, market control. Both forms have significant advantages and disadvantages that make it difficult to find what is truly best for society as a whole. The economy currently utilized in the United States is a capitalist market economy with some government intervention, which allows innovation and competition. Unfortunately, there are also many negative aspects of this economy, such as high poverty rates, homelessness, income inequality, high unemployment, and other systemic issues.

The following section is from: (Introduction to Sociology 2e)

Capitalism

Scholars don’t always agree on a single definition of capitalism. For our purposes, we will define capitalism as an economic system in which there is private ownership (as opposed to state ownership) and where there is an impetus to produce profit, and thereby wealth. This is the type of economy in place in the United States today. Under capitalism, people invest capital (money or property invested in a business venture) in a business to produce a product or service that can be sold in a market to consumers. The investors in the company are generally entitled to a share of any profit made on sales after the costs of production and distribution are taken out. These investors often reinvest their profits to improve and expand the business or acquire new ones. To illustrate how this works, consider this example. Sarah, Antonio, and Chris each invest $250,000 into a start-up company that offers an innovative baby product. When the company nets $1 million in profits its first year, a portion of that profit goes back to Sarah, Antonio, and Chris as a return on their investment. Sarah reinvests with the same company to fund the development of a second product line, Antonio uses his return to help another start-up in the technology sector, and Chris buys a small yacht for vacations.

To provide their product or service, owners hire workers to whom they pay wages. The cost of raw materials, the retail price they charge consumers, and the amount they pay in wages are determined through the law of supply and demand and by competition. When demand exceeds supply, prices tend to rise. When supply exceeds demand, prices tend to fall. When multiple businesses market similar products and services to the same buyers, there is competition. Competition can be good for consumers because it can lead to lower prices and higher quality as businesses try to get consumers to buy from them rather than from their competitors.

Wages tend to be set in a similar way. People who have talents, skills, education, or training that is in short supply and is needed by businesses tend to earn more than people without comparable skills. Competition in the workforce helps determine how much people will be paid. In times when many people are unemployed and jobs are scarce, people are often willing to accept less than they would when their services are in high demand. In this scenario, businesses are able to maintain or increase profits by not increasing workers’ wages.

Capitalism in Practice

As capitalists began to dominate the economies of many countries during the Industrial Revolution, the rapid growth of businesses and their tremendous profitability gave some owners the capital they needed to create enormous corporations that could monopolize an entire industry. Many companies controlled all aspects of the production cycle for their industry, from the raw materials, to the production, to the stores in which they were sold. These companies were able to use their wealth to buy out or stifle any competition.

In the United States, the predatory tactics used by these large monopolies caused the government to take action. Starting in the late 1800s, the government passed a series of laws that broke up monopolies and regulated how key industries—such as transportation, steel production, and oil and gas exploration and refining—could conduct business.

The United States is considered a capitalist country. However, the U.S. government has a great deal of influence on private companies through the laws it passes and the regulations enforced by government agencies. Through taxes, regulations on wages, guidelines to protect worker safety and the environment, plus financial rules for banks and investment firms, the government exerts a certain amount of control over how all companies do business. State and federal governments also own, operate, or control large parts of certain industries, such as the post office, schools, hospitals, highways and railroads, and many water, sewer, and power utilities. Debate over the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy remains an issue of contention today. Some criticize such involvements as socialism (a type of state-run economy), while others believe intervention is necessary to protect the rights of workers and the well-being of the general population.

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system in which there is government ownership (often referred to as “state run”) of goods and their production, with an impetus to share work and wealth equally among the members of a society. Under socialism, everything that people produce, including services, is considered a social product. Everyone who contributes to the production of a good or to providing a service is entitled to a share in any benefits that come from its sale or use. To make sure all members of society get their fair share, governments must be able to control property, production, and distribution.

The focus in socialism is on benefitting society, whereas capitalism seeks to benefit the individual. Socialists claim that a capitalistic economy leads to inequality, with unfair distribution of wealth and individuals who use their power at the expense of society. Socialism strives, ideally, to control the economy to avoid the problems inherent in capitalism.

Within socialism, there are diverging views on the extent to which the economy should be controlled. One extreme believes all but the most personal items are public property. Other socialists believe only essential services such as healthcare, education, and utilities (electrical power, telecommunications, and sewage) need direct control. Under this form of socialism, farms, small shops, and businesses can be privately owned but are subject to government regulation.

The other area on which socialists disagree is on what level society should exert its control. In communist countries like the former Soviet Union, China, Vietnam, and North Korea, the national government exerts control over the economy centrally. They had the power to tell all businesses what to produce, how much to produce, and what to charge for it. Other socialists believe control should be decentralized so it can be exerted by those most affected by the industries being controlled. An example of this would be a town collectively owning and managing the businesses on which its residents depend.

Because of challenges in their economies, several of these communist countries have moved from central planning to letting market forces help determine many production and pricing decisions. Market socialism describes a subtype of socialism that adopts certain traits of capitalism, like allowing limited private ownership or consulting market demands. This could involve situations like profits generated by a company going directly to the employees of the company or being used as public funds (Gregory and Stuart 2003). Many Eastern European and some South American countries have mixed economies. Key industries are nationalized and directly controlled by the government; however, most businesses are privately owned and regulated by the government.

Organized socialism never became powerful in the United States. The success of labor unions and the government in securing workers’ rights, joined with the high standard of living enjoyed by most of the workforce, made socialism less appealing than the controlled capitalism practiced here.

Socialism in Practice

As with capitalism, the basic ideas behind socialism go far back in history. Plato, in ancient Greece, suggested a republic in which people shared their material goods. Early Christian communities believed in common ownership, as did the systems of monasteries set up by various religious orders. Many of the leaders of the French Revolution called for the abolition of all private property, not just the estates of the aristocracy they had overthrown. Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, imagined a society with little private property and mandatory labor on a communal farm. Autopia has since come to mean an imagined place or situation in which everything is perfect. Most experimental utopian communities had the abolition of private property as a founding principle.

Modern socialism really began as a reaction to the excesses of uncontrolled industrial capitalism in the 1800s and 1900s. The enormous wealth and lavish lifestyles enjoyed by owners contrasted sharply with the miserable conditions of the workers.

Some of the first great sociological thinkers studied the rise of socialism. Max Weber admired some aspects of socialism, especially its rationalism and how it could help social reform, but he worried that letting the government have complete control could result in an “iron cage of future bondage” from which there is no escape (Greisman and Ritzer 1981).

Pierre-Joseph Proudon (1809−1865) was another early socialist who thought socialism could be used to create utopian communities. In his 1840 book, What Is Property?, he famously stated that “property is theft” (Proudon 1840). By this he meant that if an owner did not work to produce or earn the property, then the owner was stealing it from those who did. Proudon believed economies could work using a principle called mutualism, under which individuals and cooperative groups would exchange products with one another on the basis of mutually satisfactory contracts (Proudon 1840).

By far the most important influential thinker on socialism is Karl Marx. Through his own writings and those with his collaborator, industrialist Friedrich Engels, Marx used a scientific analytical process to show that throughout history, the resolution of class struggles caused changes in economies. He saw the relationships evolving from slave and owner, to serf and lord, to journeyman and master, to worker and owner. Neither Marx nor Engels thought socialism could be used to set up small utopian communities. Rather, they believed a socialist society would be created after workers rebelled against capitalistic owners and seized the means of production. They felt industrial capitalism was a necessary step that raised the level of production in society to a point it could progress to a socialist and then communist state (Marx and Engels 1848). These ideas form the basis of the sociological perspective of social conflict theory.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY, OpenStax, Introduction to Sociology 2e. Provided by: Rice University. Download for free at https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8423. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

In this economy, there are two active influencers in the market that have complete control over its function. There are firms, which produce goods and services for the market and receive their income from households purchasing the aforementioned goods and services. Households subsequently obtain their income from employment at the firms, provide labor for those firms, and consume the goods and services that the firms provide. This concept is known as the Circular Flow of Income, which was conceptualized by Frank Knight in 1933. This idea is a rather simple way to isolate the most important inputs and outputs of an economy. It helps visualize why certain economic impacts occur and how issues like unemployment and inflation can impact the workforce.

Inheritance and Generational Wealth

Our economic systems significantly impact the quality of life of many of our citizens, and our dimensions of difference have resulted in more challenging systemic problems for those less “fortunate”. These systemic problems have either been enabled by the social elite or political figures. An important way that political policies have contributed to social classism is through the development of generational wealth through inheritance. Inheritance is the process of passing down capital and debt from one individual to another, typically to a family member. Generational wealth can form from this, which is described as creating enough capital to pay for the living expenses of future generations without touching the principal investment. This means that wealth can continuously form from a large amount of existing wealth, providing a theoretically never-ending source of income.

This practice has been shown to have a detrimental effect on minorities in the United States. This is because it allows, for example, white families to build up and accumulate wealth while pushing minority families toward the working class. This occurs through systematic policies that enable certain groups while disenfranchising others. According to the Economic Policy Institute, “more than half of white families end up with more wealth than their parents, while only 23 percent of blacks are able to do the same.” This shows how the system in the United States has allowed certain social groups to gain a financial and social advantage over other groups.

Monetary Allocation

The United States has a history of discrimination concerning infrastructure, education, and many other public services. This has caused significant mistrust in the government and federal spending. Many Americans agree that the government spends too much, and it really should focus more of that funding on investing in underdeveloped and underfunded communities. It has been found that both a majority of African Americans and Latinos say that the government spending is not accurately distributed back to their community and their racial group, whereas a majority of white Americans found that federal spending was fair to their group. Again, it is important to recognize that if we do not invest in our communities in an equal and just manner, we fail to see the beneficial contributions of those communities to all of society.

Governmental Policy

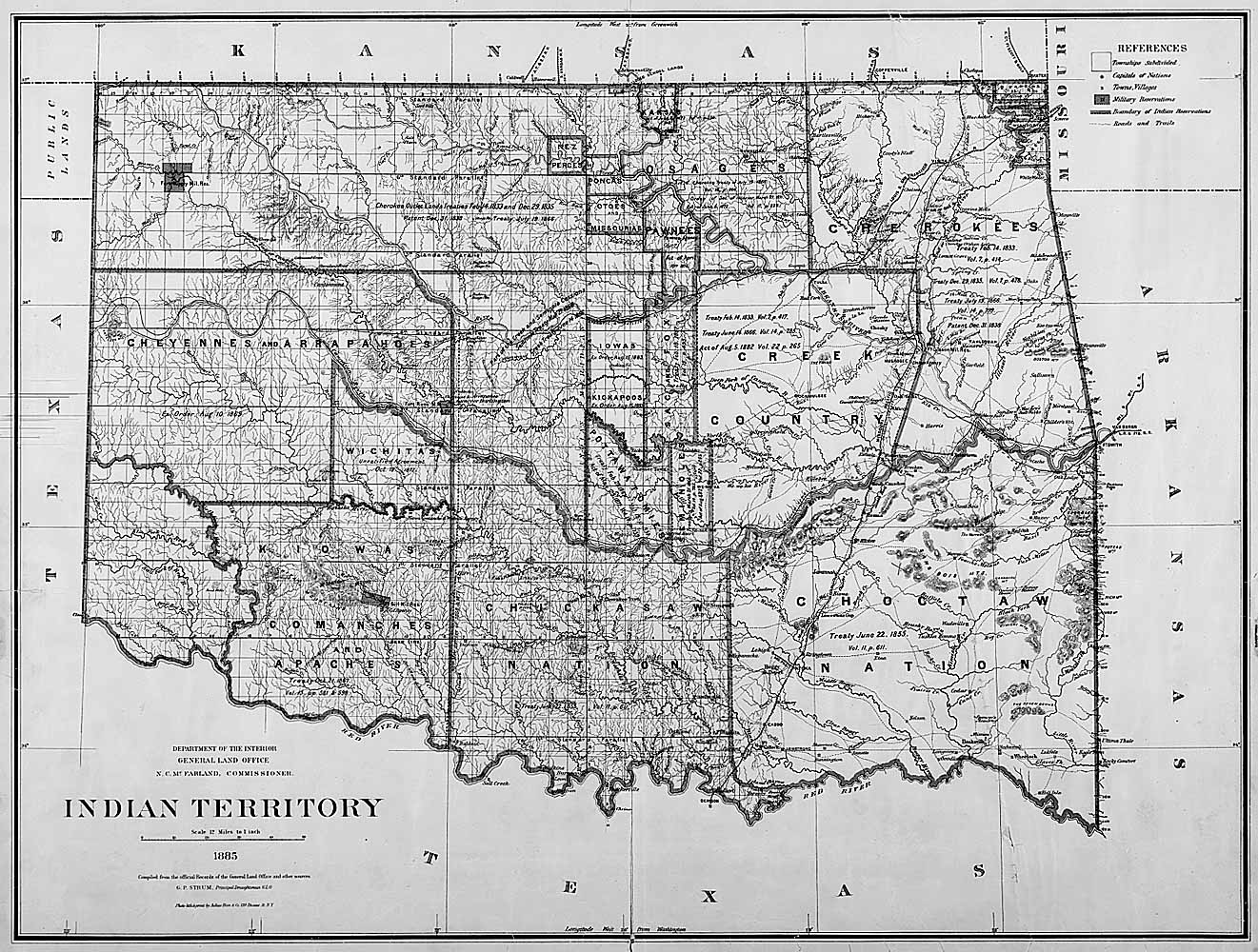

Government policies have allowed for some social groups to have more access to resources than others and deprive minorities of resources that are rightfully theirs. This has been a frequent issue in our society, and it needs to be remedied adequately. One of the most prominent examples is the Dawes Act of 1887, which divided Native American lands to integrate those communities into the current society. These lands were separated, and each member of a tribe got approximately 160 acres each, while the rest of the remaining land present was publicly sold to private citizens. This public policy perpetuated native land theft by allowing the government to separate and assimilate indigenous peoples into the capitalist market economy.

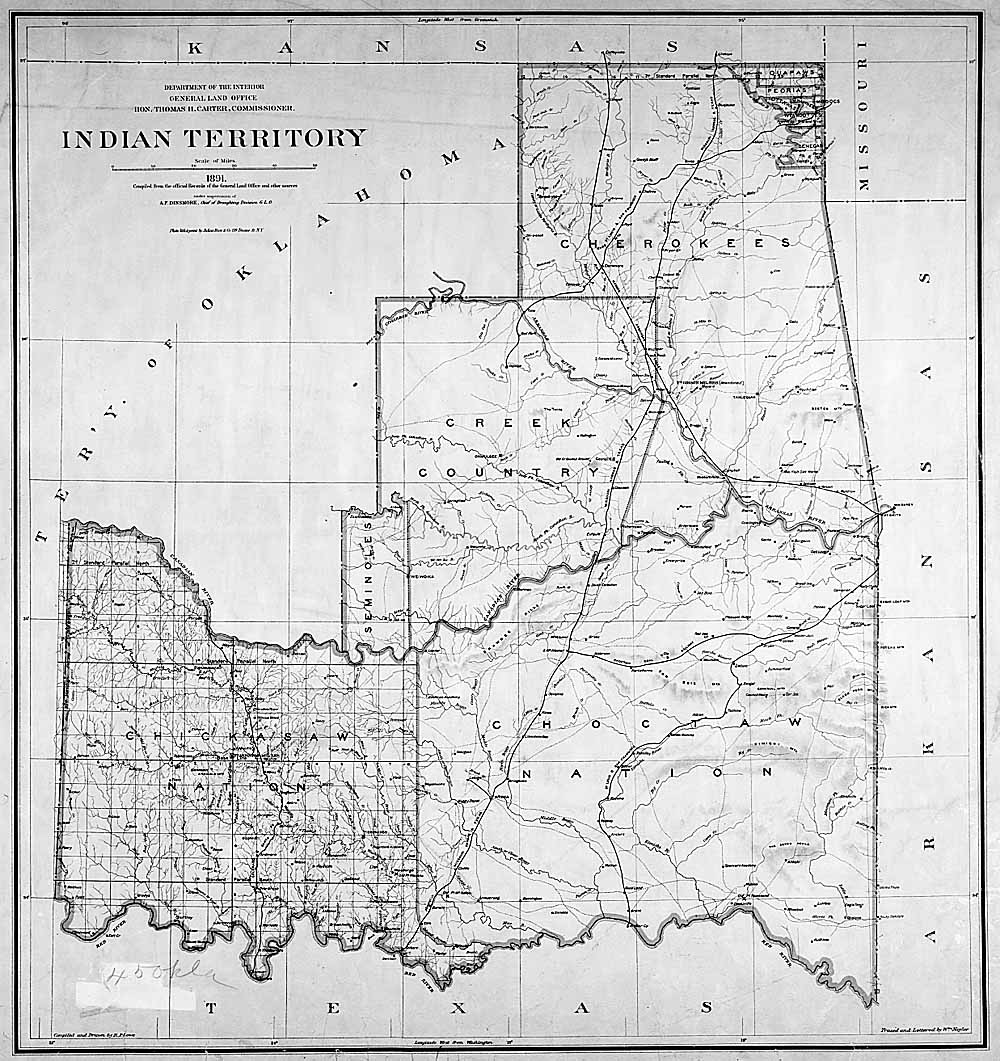

This disrupted the typical communal living style and sense of community within the tribal lands and resulted in a loss of culture, dramatically changing the way that most indigenous people lived. The total land held by tribes in the U.S. during 1881 was approximately 155,000,000 acres. By 1900, that number had dropped to 77,000,000 acres.

Federal Indian policy during the period from 1870 to 1900 marked a departure from earlier policies that were dominated by removal, treaties, reservations, and even war. The new policy focused specifically on breaking up reservations by granting land allotments to individual Native Americans. Very sincere individuals reasoned that if a person adopted white clothing and ways, and was responsible for his own farm, he would gradually drop his Indianness and be assimilated into the population. Then there would be no more necessity for the government to oversee Indian welfare in the paternalistic way it had been obligated to do, or provide meagre annuities that seemed to keep the Indian in a subservient and poverty stricken position.

On February 8, 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, named for its author, Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts. Also known as the General Allotment Act, the law allowed for the president to break up reservation land, which was held in common by the members of a tribe, into small allotments to be parceled out to individuals. Thus, Native Americans registering on a tribal “roll” were granted allotments of reservation land. “To each head of a family, one-quarter of a section; To each single person over eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section ; To each orphan child under eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; and To each other single person under eighteen years now living, or who may be born prior to the date of the order of the President directing an allotment of the lands embraced in any reservation, one-sixteenth of a section…”

Figure 1.2 Indian Territory in Oklahoma 1885 before the Dawes Act.

Figure 1.3 Indian Territory in Oklahoma 1891 after the Dawes Act.

Section 8 of the act specified groups that were to be exempt from the law. It stated that “the provisions of this act shall not extend to the territory occupied by the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, Seminoles, and Osage, Miamies and Peorias, and Sacs and Foxes, in the Indian Territory, nor to any of the reservations of the Seneca Nation of New York Indians in the State of New York, nor to that strip of territory in the State of Nebraska adjoining the Sioux Nation on the south.”

Subsequent events, however, extended the act’s provisions to these groups as well. In 1893, President Grover Cleveland appointed the Dawes Commission to negotiate with the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles, who were known as the Five Civilized Tribes. As a result of these negotiations, several acts were passed that allotted a share of common property to members of the Five Civilized Tribes in exchange for abolishing their tribal governments and recognizing state and federal laws.

In order to receive the allotted land, members were to enroll with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Once enrolled, the individual’s name went on the “Dawes rolls.” This process assisted the BIA and the secretary of the interior in determining the eligibility of individual members for land distribution.

The purpose of the Dawes Act and the subsequent acts that extended its initial provisions was purportedly to protect Indian property rights, particularly during the land rushes of the 1890s, but in many instances the results were vastly different. The land allotted to the Indians included desert or near-desert lands unsuitable for farming. In addition, the techniques of self-sufficient farming were much different from their tribal way of life. Many Indians did not want to take up agriculture, and those who did want to farm could not afford the tools, animals, seed, and other supplies necessary to get started. There were also problems with inheritance. Often young children inherited allotments that they could not farm because they had been sent away to boarding schools. Multiple heirs also caused a problem; when several people inherited an allotment, the size of the holdings became too small for efficient farming.

One other way this act affected these communities is the formation of boarding schools. These boarding schools were typically founded by Catholic churches in an attempt to try and integrate Native children into both the workforce and way of living deemed acceptable by society. The government then passed compulsory attendance laws that gave them the power to take Native children from their homes and bring them to these schools to ensure attendance. This is a clear despicable violation of the rights and liberties of these Indigenous people but also a lack of respect for the previously signed treaties and agreements surrounding the issue.

The G.I. bill is also an example of legislation only providing certain citizens with benefits like low-cost mortgages, paid higher education, low-interest loans, and other financial resources. The G.I. bill was unfortunately very discriminatory and allowed those who held significant power to prohibit African Americans from accessing these benefits. Banks could discriminate when giving out these mortgages, even though they were guaranteed by the government. In Mississippi for example, out of the 3,000 mortgages given out to veterans, two were African American, despite the population of the state is 50 percent African American. It helped a significant number of white veterans get affordable housing, whereas many black veterans couldn’t take advantage of this opportunity.

The Wage Gap in the United States

A wage gap in an economy is the average variance between the compensation of two distinct groups. Many countries have different wage gaps throughout the world, but the United States is an outlier in terms of the size of the wage gap when considering the economies of various developed countries. There are multiple different forms of wage gaps in the United States, but the two that are clearest and most prevalent wage gaps are those between genders and races. Over the past 100 years, the pay gap between genders has decreased significantly. Unfortunately, there is still a 16-cent difference between men and women when comparing jobs of similar difficulty and variety. When considering race as a factor as well, we see that Black, Native American, and Hispanic men all make 9-cents or even less for every dollar that white men make. These differences are largely due to a lack of equal opportunity and equal education among these groups. The wage gap is more varied based on how diverse their social and cultural identity is. This gap is very important to consider as a variable in the day-to-day lives of the socioeconomically disenfranchised.

The following section is from: (Introduction to Sociology 2e)

The Equal Pay Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1963, was designed to reduce the wage gap between men and women. The act in essence required employers to pay equal wages to men and women who were performing substantially similar jobs. However, more than fifty years later, women continue to make less money than their male counterparts. According to a report released by the White House (National Equal Pay Taskforce 2013), “On average, full-time working women make just 77 cents for every dollar a man makes. This significant gap is more than a statistic—it has real-life consequences. When women, who make up nearly half the workforce, bring home less money each day, it means they have less for the everyday needs of their families, and over a lifetime of work, far less savings for retirement.” While the Pew Research Center contends that women make 84 cents for every dollar men make, countless studies that have controlled for work experience, education, and other factors unanimously demonstrate that disparity between wages paid to men and to women still exists (Pew Research Center 2014).

As shocking as it is, the gap actually widens when we add race and ethnicity to the picture. For example, African American women make on average 64 cents for every dollar a Caucasian male makes. Latina women make 56 cents, or 44 percent less, for every dollar a Caucasian male makes. African American and Latino men also make notably less than Caucasian men. Asian Americans tend to be the only minority that earns as much as or more than Caucasian men.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY, OpenStax, Introduction to Sociology 2e. Provided by: Rice University. Download for free at https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8423. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

Economic Regulation

One major component of economic regulation that impacts many diverse communities is redlining. Redlining is denying systematically borrowers from a certain community. This is usually racially motivated due to an unreasonable prejudice from the lender. This occurred most frequently during the 1960s in inner-city neighborhoods. Banks would look at the racial composition of a district and the location of a potential borrower, making their decision with little regard for their actual finances. This led to those communities having less economic prosperity and further perpetuating the problem by making those communities poorer. This lack of funding in these critical communities harms economic growth and negatively impacts both the commerce and infrastructure in that part of the city or town. The federal government actively took part in this process by ensuring certain homes owned by white people in suburban neighborhoods and denying that insurance to African American homeowners due to the fear that African Americans would devalue the homes owned by the white communities. This action by the government is quite disgraceful and shows the detrimental damage that they have done to the African American community. Even though this practice is illegal in the United States and other parts of the world, it still is actively utilized by some lenders.

Introduction to Classism

Classism in the United States works on different levels and can be defined more clearly when looking at how social class is defined in the United States. This section of the chapter will define what levels classism can operate at, the social classes used in the United States, and how blue-collar and white-collar workers fit into it all.

Key Terms

Blue-Collar workers: Workers normally hold hourly jobs and are physically demanding

Classism: systematic oppression of one group by another based on economic distinctions or one’s position within the system of production and distribution

Lower Class: Those in the working poor, poverty, and underclass

Macro level: largest level which looks at the whole picture worldwide and the collective attitudes

Meso level: level of group interactions and attitudes

Micro level: level of individual attitudes and how we interact with others

Middle Class: Largest class which includes people ranging from doctors to teachers to bartenders

Social Class: How society is divided based on economic status and the lifestyle people live

Upper Class: People who hold the highest jobs in society and those in the Top 1%

White Collar Workers: workers who hold salaried or professional jobs

Classism

What is Classism?

Classism is defined as systematic oppression of one group by another based on economic distinctions or one’s position within the system of production and distribution. Classism can exist through three different levels. The first level is the micro level; oppression at an individual identity and interactions with others. The second level is the meso level; oppression at the level of group interaction. The third level is the macro level; oppression at the large level of social collectives.

Social class

One of the biggest factors in determining the survival of a passenger on board the Titanic turned out to be social class. Those people traveling with a more expensive ticket were much more likely to find themselves aboard the few lifeboats available as the Titanic sank. Why? A quick answer would be to look at the cultural norms prevalent on board. Because of the way gender, age and wealth were viewed at that time, top priority for the coveted spots on the lifeboats was given to those of a certain gender, age and wealth. The passengers who boarded the Titanic were ranked just as people living in all societies are. What is this ranking and how is it determined?

Social stratification is a system by which society ranks categories of people in a hierarchy. Some factors used include income, wealth, power, occupational prestige, and schooling. Essentially, social stratification is based on the distribution of these factors. While the factors vary from place to place, there are certain characteristics that are universal. First, social stratification is a feature in all societies. It began as societies became more complex and certain positions were afforded more prestige than others. As such, it is not a reflection of individual qualities and abilities but of the society itself. Second, social stratification carries over from one generation to the next. As an inherent character of all societies, the hierarchy of positions is passed along to each generation in the same way that other cultural norms are. Third, while social stratification is universal it is also variable. This means that while all societies rank people, by what and how varies. (In some societies a person with a higher level of education outranks a person who makes more money and vice versa.) This is also true regarding the number of inequalities present in a society. Some cultures have more while others have less. Lastly, just as the what and how varies in determining social stratification, so does the why. Different societies have different reasons behind their social stratification.

Often when we talk about social stratification, we refer to the hierarchy as one of two types of systems. In a caste system, the social stratification operates as a closed system which means that there is little opportunity to change one’s social position within the society. A caste system relies on rigid and strong cultural beliefs that insist upon people remaining at a certain social position by guiding their lives through a form of caste segregation. Members of a caste are expected to limit primary relationships to only those of the same caste that are often determined at birth (an ascribed status). Examples of this type of social stratification can be found in India where caste is determined through religion and birth or in South Africa where caste is determined by race. While both of these countries have taken steps to outlaw the caste system officially, remnants of this type of social stratification still exist due to the powerful cultural beliefs upon which they rely. The other type of system of social stratification is an open system and is referred to as a class system. Class systems rely on both ascribed statuses (those positions determined at birth) and individual achievement. A society that bases its social stratification or class system on individual achievement is a meritocracy. People are ranked within the society according to their knowledge, abilities and efforts and they expect different rewards based on their own performance. Meritocracies emerged with the rise of the Industrial Revolution as a means of improving productivity and efficiency. Despite an increased reliance on personal merit for determining social stratification, class systems still have a component based on ascribed statuses. Consider the United States as an example. While most sociologists agree that the United States rewards productive and efficient people through social mobility and a rise through class rankings, they also acknowledge the existence of “glass ceilings” that prevent too high of a rise based on gender or race. In both caste and class systems, people experience a degree of social mobility in their lifetimes- that degree to which their status can change is known as status consistency. In a system with a high degree of uniformity in a person’s status, such as a true caste system, the status consistency is labeled high. In a system with a low degree of uniformity in a person’s status (meaning a person experiences more mobility), the status consistency is labeled low.

There is a third type of society with regards to social stratification- the classless society. Existing in those societies that followed Karl Marx’s advice and set up an economy that eliminated private ownership, the classless society is supposedly free of social stratification. Do not forget the first characteristic of social stratification listed in this lesson. That it is a trait of society. While the social stratification in these supposedly “classless societies” is not based on the same elements that are found in caste or class systems, there is still social stratification. Often the hierarchy is based on political power instead. Therefore, the classless society is really more of an ideal type than one that can actually be found as real.

(Sociology Social Stratification)

What makes social class so hard to determine is that it goes further than economic. Social class is determined mostly by the lifestyle of the person. The main reason one might associate economics as the determining factor is that economics plays into the lifestyle one can have. Depending on how detailed one makes the classes determines how many classes they decide there are.

Sociologists use the term social stratification to describe the system of social standing. Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and power.

Geologists also use the word “stratification” to describe the distinct vertical layers found in rock. Typically, society’s layers, made of people, represent the uneven distribution of society’s resources. Society views the people with more resources as the top layer of the social structure of stratification. Other groups of people, with fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers. An individual’s place within this stratification is called socioeconomic status (SES).

Most people and institutions in the United States indicate that they value equality, a belief that everyone has an equal chance at success. In other words, hard work and talent—not inherited wealth, prejudicial treatment, institutional racism, or societal values—determine social mobility. This emphasis on choice, motivation, and self-effort perpetuates the American belief that people control their own social standing.

However, sociologists recognize social stratification as a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent. While inequalities exist between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns. Sociologists look to see if individuals with similar backgrounds, group memberships, identities, and location in the country share the same social stratification. No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities, but instead all participate in a system where some rise and others fall. Most Americans believe the rising and falling is based on individual choices. But sociologists see how the structure of society affects a person’s social standing and therefore is created and supported by society.

Factors that define stratification vary in different societies. In most societies, stratification is an economic system, based on wealth, the net value of money and assets a person has, and income, a person’s wages or investment dividends. While people are regularly categorized based on how rich or poor they are, other important factors influence social standing. For example, in some cultures, prestige is valued, and people who have them are revered more than those who don’t. In some cultures, the elderly are esteemed, while in others, the elderly are disparaged or overlooked. Societies’ cultural beliefs often reinforce stratification.

One key determinant of social standing is our parents. Parents tend to pass their social position on to their children. People inherit not only social standing but also the cultural norms, values, and beliefs that accompany a certain lifestyle. They share these with a network of friends and family members that provide resources and support. This is one of the reasons first-generation college students do not fare as well as other students. They lack access to the resources and support commonly provided to those whose parents have gone to college.

Other determinants are found in a society’s occupational structure. Teachers, for example, often have high levels of education but receive relatively low pay. Many believe that teaching is a noble profession, so teachers should do their jobs for love of their profession and the good of their students—not for money. Yet, the same attitude is not applied to professional athletes, executives, or those working in corporate world. Cultural attitudes and beliefs like these support and perpetuate social and economic inequalities.

(Introduction to Sociology 3e)

Upper Class

The upper class as defined for this section includes the Top 1%. However, some may put the Top 1% in their own class because of some of the differences in lifestyles that the Top 1% ‘s money can support. Some examples of jobs people in the upper class may have include institutional leadership, heads of multinational corporations, heads of foundations, and heads of universities.

The factors that affect social stratification in America include income, wealth, power, occupational prestige and schooling. An income is the monetary earnings a person receives from work or investments. In recent decades the gap between the highest incomes compared to the lowest incomes in America expanded greatly. If you look at the map below, you can see where the United States lies according to national income disparities in comparison to other nations- the darker the color of the nation implies the greater the income disparity. As you can see, the United States is well behind other comparably wealthy nations with regards to income disparity.

Even more pronounced is the difference of wealth in America. Wealth is the total value of money or other assets that an individual owns minus any debts. Wealth inequality measures the difference in how much money and other assets individuals have accumulated. According to one study, the wealthiest 160,000 families in America have as much wealth as the poorest 145 million families in America, making wealth inequality roughly ten times greater than income inequality. The pie chart below illustrates this wealth inequality, the vast majority of the wealth in America- nearly 3/4ths of American wealth- is owned by 10% of the population.

Many sociologists argue that the previous social stratification factor, wealth, affects the next factor- power. Politics is the social institution that distributes power and sets a course of action for a society. Sociologists developed many theories as to how power is disseminated and who is given authority to establish community priorities and make communal decisions, but three stand out the most.

Pluralist Model

Applying the Structural-Functional Approach, this analysis of politics recognizes the spreading of power among different groups. As resources to accomplish individual goals are limited, these different groups compete with one another to push forward their own agendas at the expense of other interest groups. This model sees the United States as a functional and true democracy since power is widely spread throughout society giving all people a voice.

Power-Elite Model

The Social-Conflict Approach, argues that power is consolidated mostly among the wealthy. The name of this model stems from the term coined by C. Wright Mills text annotation indicator in 1956- “power-elite.” According to Mills, the “power-elite” is a group made up of individuals who are either very wealthy, top political officials or high-ranking military officers (or some combination of those three). This group moves through the most powerful levels of the American branches of government and gradually concentrates all authority into their own hands. As a result, their voices have become so strong that they drown out the rest of American voices with the result that the United States is not really a democracy where the people rule- rather it is a government where the “power-elite” rule.

(For example, if Mills were alive today, he would point to the same names that repeatedly hold different political offices or advisory positions within the American government over periods of decades.)

Marxist Political-Economy Model

Applying the Social-Conflict Approach again, this analysis of politics unites the political with the economic. Unlike the Power-Elite Model that claims certain individuals are responsible for usurping the power from the people, the Marxist Political-Economy Model argues that a capitalist economy creates a system that pushes certain individuals into positions of total power. This model would agree that the United States is not a real democracy but due to its overall economic system rather than due to the actions of any specific individuals.

A fourth factor in American social stratification is occupational prestige. How often do you hear people ask what others do for a living? Depending on the answer, people make judgments on the amount of respect another should receive. Those people doing the types of work that are considered more important commandeer more respect from others and vice versa.

The last factor is schooling or education. This factor has a direct impact on income and occupational prestige. Theoretically, the higher the level of education achieved, the higher the income and social position expected.

In America, these factors combine to create a social stratification that divides Americans into classes. Depending on whom you ask, you will hear a number of different class categories describing American social stratification; but most sociologists agree on four main class categories with some sub-categories.

(Sociology Social Stratification)

The upper class is considered the top, and only the powerful elite get to see the view from there. In the United States, people with extreme wealth make up one percent of the population, and they own roughly one-third of the country’s wealth (Beeghley 2008).

Money provides not just access to material goods, but also access to a lot of power. As corporate leaders, members of the upper class make decisions that affect the job status of millions of people. As media owners, they influence the collective identity of the nation. They run the major network television stations, radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, and sports franchises. As board members of the most influential colleges and universities, they influence cultural attitudes and values. As philanthropists, they establish foundations to support social causes they believe in. As campaign contributors and legislation drivers, they fund political campaigns to sway policymakers, sometimes to protect their own economic interests and at other times to support or promote a cause. (The methods, effectiveness, and impact of these political efforts are discussed in the Politics and Government chapter.)

U.S. society has historically distinguished between “old money” (inherited wealth passed from one generation to the next) and “new money” (wealth you have earned and built yourself). While both types may have equal net worth, they have traditionally held different social standings. People of old money, firmly situated in the upper class for generations, have held high prestige. Their families have socialized them to know the customs, norms, and expectations that come with wealth. Often, the very wealthy don’t work for wages. Some study business or become lawyers in order to manage the family fortune. Others, such as Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian, capitalize on being a rich socialite and transform that into celebrity status, flaunting a wealthy lifestyle.

However, new-money members of the upper class are not oriented to the customs and mores of the elite. They haven’t gone to the most exclusive schools. They have not established old-money social ties. People with new money might flaunt their wealth, buying sports cars and mansions, but they might still exhibit behaviors attributed to the middle and lower classes.

(Introduction to Sociology 3e)

Middle Class

Because of how large the economic and lifestyle range is in the middle class, it is commonly split into upper middle class, lower middle class, and the working class. It is easiest and most common in the middle class to use jobs as a differentiating factor because there is a tendency for those with the same job to have a pretty similar lifestyle although it can differ person to person and how they personally choose to live. The upper middle class represents a high level of scientific and technological knowledge. These people include people such as Doctors, Pharmacists, and School Administrators. The lower middle class is made of people who work jobs such as clerical, professional support, data collection, paralegal, and blue-collared workers who are skilled in a trade. The last section of this class is the working class. Workers in the working class can include craft workers, factory workers, restaurant workers, nursing home staff, repair shop/ garage employees, delivery service workers, and government employees. This basically means anyone who works minimum wage and can support themselves. For this section it will detail the middle class as a whole and will be kept together.

Many people consider themselves middle class, but there are differing ideas about what that means. People with annual incomes of $150,000 call themselves middle class, as do people who annually earn $30,000. That helps explain why, in the United States, the middle class is broken into upper and lower subcategories.

Lower-middle class members tend to complete a two-year associate’s degrees from community or technical colleges or a four-year bachelor’s degree. Upper-middle class people tend to continue on to postgraduate degrees. They’ve studied subjects such as business, management, law, or medicine.

Middle-class people work hard and live fairly comfortable lives. Upper-middle-class people tend to pursue careers, own their homes, and travel on vacation. Their children receive high-quality education and healthcare (Gilbert 2010). Parents can support more specialized needs and interests of their children, such as more extensive tutoring, arts lessons, and athletic efforts, which can lead to more social mobility for the next generation. Families within the middle class may have access to some wealth, but also must work for an income to maintain this lifestyle.

In the lower middle class, people hold jobs supervised by members of the upper middle class. They fill technical, lower- level management or administrative support positions. Compared to lower-class work, lower-middle-class jobs carry more prestige and come with slightly higher paychecks. With these incomes, people can afford a decent, mainstream lifestyle, but they struggle to maintain it. They generally don’t have enough income to build significant savings. In addition, their grip on class status is more precarious than those in the upper tiers of the class system. When companies need to save money, lower-middle class people are often the ones to lose their jobs.

(Introduction to Sociology 3e)

Lower Class

Just like the Upper class, this class has two major divides; the working poor and those in poverty. The working poor are those who work full time jobs but make less than minimum wage. Many put the working class above the poor and remove the title lower class all together. In many cases those in poverty will be referred to as the underclass because they don’t make enough money to support any type of lifestyle, making them below the classing system.

The lower class is also referred to as the working class. Just like the middle and upper classes, the lower class can be divided into subsets: the working class, the working poor, and the underclass. Compared to the lower middle class, people from the lower economic class have less formal education and earn smaller incomes. They work jobs that require less training or experience than middle-class occupations and often do routine tasks under close supervision.

Working-class people, the highest subcategory of the lower class, often land steady jobs. The work is hands-on and often physically demanding, such as landscaping, cooking, cleaning, or building.

Beneath the working class is the working poor. They have unskilled, low-paying employment. However, their jobs rarely offer benefits such as healthcare or retirement planning, and their positions are often seasonal or temporary. They work as migrant farm workers, housecleaners, and day laborers. Education is limited. Some lack a high school diploma.

How can people work full-time and still be poor? Even working full-time, millions of the working poor earn incomes too meager to support a family. The government requires employers pay a minimum wage that varies from state to state, and often leave individuals and families below the poverty line. In addition to low wages, the value of the wage has not kept pace with inflation. “The real value of the federal minimum wage has dropped 17% since 2009 and 31% since 1968 (Cooper, Gould, & Zipperer, 2019). Furthermore, the living wage, the amount necessary to meet minimum standards, differs across the country because the cost of living differs. Therefore, the amount of income necessary to survive in an area such as New York City differs dramatically from small town in Oklahoma (Glasmeier, 2020).

The underclass is the United States’ lowest tier. The term itself and its classification of people have been questioned, and some prominent sociologists (including a former president of the American Sociological Association), believe its use is either overgeneralizing or incorrect (Gans 1991). But many economists, sociologists government agencies, and advocacy groups recognize the growth of the underclass. Members of the underclass live mainly in inner cities. Many are unemployed or underemployed. Those who do hold jobs typically perform menial tasks for little pay. Some of the underclass are homeless. Many rely on welfare systems to provide food, medical care, and housing assistance, which often does not cover all their basic needs. The underclass have more stress, poorer health, and suffer crises fairly regularly.

(Introduction to Sociology 3e)

Social Class as a Macro Level

Global stratification compares the wealth, status, power, and economic stability of countries across the world. Global stratification highlights worldwide patterns of social inequality.

In the early years of civilization, hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies lived off the earth and rarely interacted with other societies. When explorers began traveling, societies began trading goods, as well as ideas and customs.

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution created unprecedented wealth in Western Europe and North America. Due to mechanical inventions and new means of production, people began working in factories—not only men, but women and children as well. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, industrial technology had gradually raised the standard of living for many people in the United States and Europe.

The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of vast inequalities between countries that were industrialized and those that were not. As some nations embraced technology and saw increased wealth and goods, the non-industrialized nations fell behind economically, and the gap widened.

Sociologists studying global stratification analyze economic comparisons between nations. Income, purchasing power, and wealth are used to calculate global stratification. Global stratification also compares the quality of life that a country’s population can have. Poverty levels have been shown to vary greatly across countries. Yet all countries struggle to support the lower classes.

Models of Global Stratification

In order to determine the stratification or ranking of a country, economists created various models of global stratification. All of these models have one thing in common: they rank countries according to their economic status, often ranked by gross national product (GNP). The GNP is the value of goods and services produced by a nation’s citizens both within its boarders and abroad.

Another system of global classification defines countries based on the gross domestic product (GDP), a country’s national wealth. The GDP calculated annually either totals the income of all people living within its borders or the value of all goods and services produced in the country during the year. It also includes government spending. Because the GDP indicates a country’s productivity and performance, comparing GDP rates helps establish a country’s economic health in relation to other countries, with some countries rising to the top and others falling to the bottom. The chapter on Work and the Economy (specifically the section on Globalization and the Economy) shows the differences in GDP among various countries.

Traditional models, now considered outdated, used labels, such as “first world”, “second world,” and “third world” to describe the stratification of the different areas of the world. First and second world described industrialized nations, while third world referred to “undeveloped” countries (Henslin 2004). When researching existing historical sources, you may still encounter these terms, and even today people still refer to some nations as the “third world.” This model, however, is outdated because it lumps countries together that are quite different in terms of wealth, power, prestige, and economic stability.

Another model separates countries into two groups: more developed and less developed. More-developed nations have higher wealth, such as Canada, Japan, and Australia. Less-developed nations have less wealth to distribute among populations, including many countries in central Africa, South America, and some island nations.

GNP and GDP are used to gain insight into global stratification based on a country’s standard of living. According to this analysis, a GDP standard of a middle-income nation represents a global average. In low-income countries, most people are poor relative to people in other countries. Citizens have little access to amenities such as electricity, plumbing, and clean water. People in low-income countries are not guaranteed education, and many are illiterate. The life expectancy of citizens is lower than in high-income countries. Therefore, the different expectations in lifestyle and access to resources varies.

(Introduction to Sociology 3e)

Social stratification exists in all societies. The poor and wealthy and everyone in between live in all of the nations on our planet. However, the heights of the wealth and the depths of the poverty vary drastically depending on the nation. Most of America’s poor experience relative poverty. This means that they lack what is taken for granted by the rest of society. When we shift the topic to include a global perspective we find another prevalent type of poverty, absolute poverty. Those who live in absolute poverty experience life threatening conditions. When we study the almost two hundred other nations in the world, we find a glaring variety in the economic conditions in which people live. The map below displays the percentage of a nation’s population that lived on less than $1.25 a day according to the United Nations during the period between 2000 and 2006. Sociologists generally agree that people living on less than $1 a day have reached the absolute poverty level.

As you can surmise from this map, absolute poverty is very present in some parts of the world. There is also a very stark contrast between those nations that “have” and those that “have not” to borrow a perspective from Karl Marx. Global stratification is a comparison of the economic stability, power, status and wealth between nations (rather than between individuals) that focuses on the unequal distribution of resources. Every nation has wealthy citizens; therefore, global stratification reveals itself more through the patterns of social inequality found in the social stratification within each nation. Just as sociologists categorize the different classes in social stratification, so too do they categorize the different classes in global stratification. One of the first socioeconomic models used to classify global stratification divided the planet into First, Second and Third World Countries. Developed during the Cold War that followed World War II, this model referred to rich, industrial nations as the First World, nations that were part of the Communist Bloc as the Second World, and non-industrialized nations as the Third World. There were several problems with this model as it was very ethnocentric, did not take into consideration the variety found within the nations lumped together, and reflected cold war politics more than it explained global economic reality. With the demise of the Soviet Union as a communist nation in the 1990s, accompanied by the fall of communism in other European nations, this model went out of favor. After all, there was no longer a Second World. The model that replaced it divided the planet again into three categories, but this time according to standards of living rather than by political or economic systems. In this sense, the new classification model resembles the class system used in the United States to classify social stratification as it is based on per capita income. Sociologists use the terms High Income, Middle Income and Low Income Countries to differentiate between the nations of the world as they study global stratification and classify nations. High Income Countries have the highest standards of living with comparatively high incomes per capita and a long history of industrialization that has now entered the post-industrial stage. Middle Income Countries have average standards of living with incomes per capita that resemble the global national average. Low Income Countries are those nations with the lowest standards of living and the highest populations to experience absolute poverty. These are the nations most afflicted by those characteristics associated with global poverty:

Reduced presence of technology

High population growth

Rigid cultural norms based on tradition

Extreme social stratification differentiating between the wealthiest and the poorest

High levels of gender inequality

Weak international relationships with little global power

(Sociology Social Stratification)

Blue-Collar vs White-Collar Workers

There are different types of collared workers that have been defined in the past few years. Despite this fact, the past has only defined two types of workers: blue-collar and white-collar. Because the past has only defined these two workers, most statistical data and definitions revolve around this and is what is going to be used in this section.

White collar workers are those that hold salaried or professional jobs. These workers usually do not perform manual labor. These jobs require formal education and training. These workers are found in the Upper and upper middle classes but can go down to lower middle class in some cases.

Blue Collar workers hold hourly jobs. They usually hold jobs that involve physical tasks and skills can be acquired relatively quickly. These workers are found mainly in the lower middle class through lower class.

One study that was conducted to show some of the differences between blue-collar lifestyles and white-collar lifestyles was conducted on students. The students in particular were blue-collar students from lower income households who enrolled in business school; which for the most part is made for white-collar lifestyles. The study made two key observations. The first key observation was the lack of connection to the material that the students felt. Due to business schools being geared to the white-collar lifestyles, they are set up in a way that white-collar students learn, including time spent outside of school with homework and extracurriculars. The second key observation came to the mental distinctions in culture that the students faced. At school they were the outcasts for being blue-collar. At home, they were outcasts and seen as white-collar.

This study has led to interesting debates over how society is set up. Because children of a certain collar class are being raised in a certain way dependent on that collar class, there is a cycle put into place. This cycle is keeping certain people from changing their place in society. Because of how closely related the collar system is to a person’s socioeconomic status, this often means that children are often stuck in a social class that their parents were in. This also means that most of the wealth is stuck in the same set of people as well which makes it harder for those in lower classes to move up in status.

Systemic Problems with the Economy

In the United States, there are several systemic problems with the economy and how classism is viewed. These problems have existed for years upon years and we have gained little movement towards beneficial change. A few examples include housing discrimination, distribution of wealth, racism, and the wage gap. All of them need to be addressed and changed, but this essay will focus on four specific topics. The four main problems within the U.S. economy and classism are wealth inequality, poverty, healthcare, and women’s reproductive healthcare.

Wealth Inequality

The United States divides into three classes, the lower class, middle class, and upper class. Within the upper class, there is the top 1%, which are the individuals that hold around 40% of the national wealth (0:30, How wealth inequality is dangerous for America). The top 1% reign with millions to even billions of dollars with the majority of the money coming from inheritances. For example, the founder of Walmart, Sam Walden has six heirs, and combined they have over $140 billion dollars from doing no work whatsoever (1:08, How wealth inequality is dangerous for America). These six heirs have more money than the bottom 40% of Americans, which is around 125 million people. This is a major problem within the United States because there are numerous people that have so much wealth only because they were born into the right family at the right time. In order to fix problems with wealth inequality, people need to recognize that others are struggling. People are living paycheck to paycheck and sometimes they have to decide between dinner or washing their clothes for the day. This is a struggle that people with millions of dollars don’t have to decide between. They can do both and even buy the newest iPad for their daughter. However, America is an extremely greedy country, so it’s incredibly difficult to implement or create such recognition and change.

Poverty

In 2019, 12.4% of Americans lived in poverty, which is around 316 million people (povertyusa.org). In addition, poverty is not distributed equally amongst the different races. The majority of Americans that are in poverty are white, but this is only 11.1% of the poverty population. Native Americans actually take the biggest hit with 24.9% of their population living in poverty. That means that every 1 in 4 Native Americans lives in poverty. A lot of the issues within poverty come from the mindsets and ideologies of the middle class and upper-class citizens. Others assume that people are in poverty because of their own personal failings. According to Frances Fox Piven, an author for The Progressive Magazine, “when household income increases, other problems like poor school performance or drug use tend to diminish” (21). Therefore, in order to reduce the poverty levels in the United States, we need to recognize them as actual people and not as failures. It is most important to have recognition from the community and government since they can have the most impact on changing poverty.

Healthcare

In the U.S., healthcare is extremely expensive compared to the yearly median household income, which is $67,521 (US Census Bureau 2020). Simply going to the emergency room for a sore throat will cost you $620 (Mira healthcare). To get an air ambulance, it will cost you $12,000-$25,000 (NAIC). This means that if you get stuck out in the grand canyon and need an air ambulance, it could cost 66% of your yearly household income. Now, that is an outrageously expensive “one-day trip”. For some people, healthcare is so expensive that they don’t go to the hospital when they most definitely need to. Around 8.8% of Americans live without health insurance (povertyusa.org). Without health insurance, this leads to even poorer health outcomes, more likeliness to get diagnosed with a disease at a later and more advanced stage, and more likely to have a higher mortality rate (Borchelt).

Healthcare for Women

Women take the biggest hit from expensive healthcare compared to men. Around five million more women live without healthcare than men (povertyusa.org). As well, around one in four women have delayed or gone without care because of the cost (Borchelt). More specifically, reproductive health care and preventative health care are especially important for women. However, there have been some cutbacks on funding for this type of care. The Trump administration cut funds on the Affordable Care Act which means less funding for Medicaid, the Title X program, and Planned Parenthood (Borchelt). These are all resources that specifically target people in poverty, minorities, and women. A cut back on funds means less access to abortion, affordable counseling, STD tests, birth control, mammograms, and even reproductive cancer diagnoses. Borchelt explains that “our laws, policies, and courts need to recognize the reality of poor women’s lives. Poor women need access to quality, affordable comprehensive health care that includes reproductive healthcare.” Access to healthcare is important for everyone but is significantly more important for women, especially for pregnancy and reproductive wellness.

Conclusion

While social class is so hard to clearly define, it plays a vital role in how people see the world. On a basic level, social class in the United States can be split into the Upper class, Middle class, and Lower class. Each of these is defined and directed by the lifestyles of people influenced by people’s economic status. All of this is overlapped with the differences in blue-collar and white-collar jobs increases the divide that can be seen when looking at social class in the United States. Within Sysmteic Problems with the Economy, there were four important problems that need to be addressed within the U.S. economy and views of classism. Inheritance and wealth inequality need to be recognized and dealt with by the government through taxation or other methods. However, the people who are in the government have a lot of money and don’t want to give that up. People who are living paycheck to paycheck also need to be recognized. They need to be seen as people and treated humanely for us to lessen the poverty rates in the United States. Lastly, healthcare needs to be easily accessible to everyone. Healthcare lessons mortality rates and makes it easier to cure diseases before it’s too late.