1 Make/Do: Gussied-Up Garbage Making a Speed Bump for Fast Fashion

Jessica Larson

Make do is an idiom. Grammatically, it is a verb phrase, and it means to use what one has on hand or to persevere through non-ideal circumstances.[1]

If you’re in academia for any stretch, you come to understand that systemic change does not come easy, unanimity is rare, and anything/everything can and will be discussed (nearly) to death before consensus is reached. In 1999, during the University of Minnesota’s (UMN’s) transition from quarters to semesters, I was told by a sage senior colleague that “people like progress, but hate change.” This has remained often maddeningly true in my 26 years teaching at the University of Minnesota Morris (UMM). The constant tussle is simply how we work things out, and contrariness is baked into the process.

But with notable non-contrariness, for nearly 20 years the UMM community has embraced and built upon its commitment to making a sustainable community thrive in the western region of Minnesota (https://morris.umn.edu/sustainability-umn-morris). This is one of the things I treasure most about my campus, that this green orthodoxy has become second nature to our collective work and life on campus. Faculty, staff, and students hold great pride in it, and love talking about it.

The two wind turbines that perch on the edge of town are the focus of sincere affection, artistic tributes, and fandom; mere mention in any public address will generate a “whoop!” from the audience. (“We operate off the grid, ya know…sell electricity back!”) The biofuel plant, while not always getting the superfan treatment, is a stalwart during the long cold Minnesota winters, keeping our buildings warm and comfortable. (“We burn stuff from fields around here!”) Garbage cans have been shrinking relative to the size and number of recycling and compost bins that replace them. (“But I think we could use a few more, right?”) More devout recyclers on campus are often witnessed rooting around these containers and re-sorting items that out of place. (“I’ll catch up in a bit—I just saw someone toss an apple core in the trash….”) The compost pile’s pH levels are publicly discussed, a new destination for pizza boxes made the news, and we’ve proven that icy sidewalks can be managed without harsh chemicals. And most importantly, each year we send graduates into the world armed with the skills to sort and source, and to expect more from their communities, and we welcome a new batch of students to our campus, quickly zipper-merging them into our sustainable practices with an efficiency that would make MNDoT jealous.

Making Do, Making Sense of What We Do

Since 2007, UMM has had a robust environmental studies major that draws from an interdisciplinary offering of courses, but it included only a smattering of courses from the humanities and no arts courses. Instead, the majority of campus resources focused on areas in science and social science, where research could address issues in agriculture, environmental regulations, energy, and land use. In 2007, theatre and studio art faculty began conversations about leveraging our curricular contributions to the “renewable, sustainable education” that the institution was promising its recruits.

We already recycled. Everyone in the arts did, but it was driven less by the desire to reduce landfill waste than it was by the need to reduce costs. Having learned the basics from our Depression-era grandparents, for whom cutting costs was at first a matter of survival and then a lifelong habit of “making do,” we married that philosophy to our studio practices and careers in an era that doesn’t value artists (or the arts) relative to venture capitalists. Our challenge at UMM was to work within a budget still at 1990s levels while teaching students who predominantly came from low-income or first-generation households and had limited access to or ability to purchase materials, especially in a city three hours from an art supply store. We had to be savvy to find resources that taught students the traditions of the arts while stretching a budget once serving 25–30 students and now handling 60–70.

In conversations about sustainability, none of this seemed very “sexy.” We told students that this is how you could afford to be a maker while managing other financial responsibilities. Lumber could be recycled for sets and painting stretchers, newsprint bought dirt cheap from regional printing presses discarding their endrolls, rags sourced from the thrift store’s rejected clothing pile and cut by hand, costumes reconfigured, felled trees carved…all tasks taken on by UMM faculty over the years to offer a fulfilling curriculum at a fraction of the cost.

Additionally, while a lot of artmaking processes are historically toxic—arts faculty saw the negative impacts of those chemicals on our mentors and teachers—we’ve made efforts to reduce exposure to mineral spirits, acids, and other excess chemicals from our processes and to find newer, safer processes, improving safety for ourselves and our students, and protecting the groundwater as well.

Offering occasional productions or exhibits promoting ideas of eco-conscious art was a start, but only a preliminary step as we worked to engage students in their own research and creative output. We were all looking for something that reflected our own values within the mission at UMM, something that played to our strengths teaching the fundamentals of design, materiality, and the importance of the artist in society to question and innovate within a liberal arts tradition.

Make It Work, 2009–2018

The idea for Fashion Trashion came from an episode of Bravo’s popular reality show Project Runway, where contestants were challenged to use e-waste exclusively to make a garment. I was teaching another year of 3D Design in our major’s foundations sequence, and had a budget of $20 per student for the entire semester of projects. Students had been dutifully assembling cardboard and other found objects into collages and assemblages, much like I did as a student, and I figured they were as bored with this as I was. My colleagues and I put great effort into elevating the traditional foundation courses, looking for ways to teach the basics while inspiring students to create works that are timely and of personal interest.

The idea of making a garment from found materials touched on everyone’s relationship with clothing/fashion, and the body became a form that could be referenced by the sculptural ideas and processes of other works students were making in class. The Project Runway structure added a game-like atmosphere—limits on using actual fabric, working within certain period styles and silhouettes—and I thought the students would enjoy having to think around a set of specific limitations to solve the visual problem. It was also an interesting and somewhat unexpected approach to making students think about three-dimensional forms, sustainability, and construction. Ever since Scarlet O’Hara refashioned drapery into a dress in Gone With The Wind (and Carol Burnett hilariously lampooned it several decades later), clothing and textiles have naturally lent themselves to being malleable—deconstructed and reconstructed with non-textile materials, all in the name of fashion.

The rules were simple: make a wearable garment for yourself using only materials that are repurposed, reimagined, and unexpected; observe strict limits on the use of fabric, and draw your designs from any historical or editorial fashion area of interest. Students had to be able to wear their own creations for the final reveal. Garments had to fall within chosen categories of period garment, avant garde, or non-garment. For my part, I was thrilled to assume the role of the show’s designer/mentor, Tim Gunn, nudging the students with his signature instruction to “make it work” as they broke down soda cans, boxes, and plastic bags in novel ways for their creations. We used online resources to learn how to fuse plastic bags with heat, crochet VHS and cassette tapes, and make chainmail from pop tabs and “sequins” from pieces of aluminum cans. We put out calls on the campus listservs for materials, and folks were more than happy to help us collect old coffee filters, drink pouches, candy wrappers, or whatever bit of minutiae we sought.

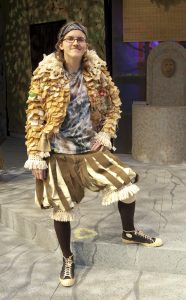

The final critique was a public event, a runway show in the school’s Edward J. and Helen Jane Morrison Gallery, replete with faculty/staff “celebrity” judges and prizes for titles like “Dumpster Diva,” “Rubbish Strutter,” and “Radical Refuse.” The students walked a runway to loud music, posed along the way, answered questions, and played to the audience, building performative identities with costume, makeup, and attitude that were much different from their everyday personas.

Since that first runway show in 2009, Fashion Trashion has grown to be a hot ticket on campus, drawing a dedicated audience from across the campus and with students’ families traveling to participate in the event. We insist that the atmosphere be fun, a bit bawdy, and campy. Faculty and staff have been eager to volunteer as judges (some dressing as famous designers or fashionistas). The gallery eventually proved too small for the event, so we collaborated with the Theatre program to use stage areas and seating—and coordinated the shows with lighting design classes, providing students with applicable and semi-professional experience.

As the project evolved, I was able to move Fashion Trashion to its own course heading, and offer one credit to non majors looking for an arts or sustainability experience. The course was attractive to theatre students wanting more costuming experience, and in 2010 I collaborated with Theatre Professor Ray Schultz to design a sustainable production of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, expanding the assignment’s original principles to source the production’s costumes and set. We were able to expand research opportunities for 20 undergraduate arts students and 50 additional non majors, creating work teams that took on specific design and construction tasks. The production ultimately contained 85–90% repurposed items and its total costs came in at less than $850. We completed our second “Greened-Bard” production in 2016 by repeating the formula to stage A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream at UMM.

2020, Make and Do (Something About Fast Fashion), plus COVID

I’m running out of closet room for my t-shirts. My own fault, as I’m a sucker for those 2-for-$20, $9.99, 50% sales…and even though I tell myself that I have plenty (some still in packaging), I still buy them. But I’ve stopped taking those free, commemorative t’s that are always being given away on campus—or if I give in, I get them in my dad’s size. As a retiree who refuses to buy new t-shirts, he’s done more to advertise UMM than I have, going about his business in shirts for symposia and events that he never attended. But as the shirts pile up, it occurs to me: I have a problem with fast fashion, and because of fast fashion, I am a problem.

By the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) projections, the average U.S. resident generates 82 pounds of textile waste annually. Only about 15% of textiles end up being recycled, while 11 million tons of discarded textiles go to the landfill.

And those t-shirts I adore? They require 700 gallons of water to produce. Each.

For Fall 2020, I expanded the Fashion Trashion course to incorporate a project exploring textile/clothing waste in global sustainability efforts, and this became my focus as an Educational Fellow at IonE. We were going to take on the t-shirt. It’s our common uniform, and can be obtained in bulk from donation centers to use as the base material for an array of projects, from making reusable shopping bags to “yarn.” I also wanted to develop a unit in which students learned basic clothing repair and visually expressive mending techniques like sashiko stitching and bordo. I envisioned a workshop experience in which my students could try a number of techniques and not only reimagine their own garments, but do repairs for members of the UMM and Morris communities.

Then, COVID.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 and the protocols that made in-person teaching feasible at UMM severely limited students’ studio time, and the semester was made more challenging when class members had to self-isolate if exposed or testing positive. I decided to pare back the scope of the projects to ensure they could be completed in non-studio environments using hand-sewing processes rather than machine-based ones. Using the timely focus on people’s immediate and interior lives created by our collective isolation, I asked students to create an inventory of their clothing, noting years owned, place of manufacturing, condition, and whether made, purchased, or bought. We then had a lengthy online discussion about our habits in accumulating clothing and about the global origins of these items. While this might be more common to my students at UMM, or perhaps a coincident of this class, I was amazed to learn that the majority of students in the course were very frugal—one student going so far as to primarily wear clothing he found discarded!

For the final project, the class settled on talking about the impact of denim. Americans buy an average of four pairs of jeans a year, and the related water waste and pollution disproportionately affect the Asian communities producing these garments. Students adapted one of the hand techniques taught in class to alter or mend a pair of jeans (or other item if they chose), assembling their own sewing kits with needles, scissors, different kinds of threads, and fabric scraps I had been collecting for years. While the final results may have been less monumental than taking on a mound of discarded t-shirts, for many of the students, learning to repair a pair of jeans or make an uninteresting pair suit them personally unlocked a new kind of confidence to make their clothes last longer and help family and friends do the same.

For the final project, the class settled on talking about the impact of denim. Americans buy an average of four pairs of jeans a year, and the related water waste and pollution disproportionately affect the Asian communities producing these garments. Students adapted one of the hand techniques taught in class to alter or mend a pair of jeans (or other item if they chose), assembling their own sewing kits with needles, scissors, different kinds of threads, and fabric scraps I had been collecting for years. While the final results may have been less monumental than taking on a mound of discarded t-shirts, for many of the students, learning to repair a pair of jeans or make an uninteresting pair suit them personally unlocked a new kind of confidence to make their clothes last longer and help family and friends do the same.

Making a way forward

Recycle, reduce, reuse…I think the recycle and reduce parts come easier to most people, including those in my campus community. We all want to eliminate chemicals from our daily habits and processes, and there’s something satisfying about finding a place for that thing you need to be rid of—it’s even a little bit praiseworthy to prevent that item from languishing in a landfill. But reuse? That’s the one we collectively struggle with as we learn how much of those donated and recycled items really do end up in those landfills we sought to avoid. This is the hardest work for all of us, to collectively interrupt habits of consumption and figure out how to make more out of what we have at hand. But the Arts have been ready for it. For the University of Minnesota Morris campus, Fashion Trashion and Sustainable Shakespeare productions have made the theoretical tangible, shown possibilities in these lowly products and unwanted items, and inserted creativity as a necessary skill for moving toward a more perfect vision of global sustainability. We also proved that it can be fun. It is through playful imagining and tinkering that we’re going to find new ways to unlock the potential of materials and the production of goods on and off the runway or stage.

- (https://writingexplained.org/) ↵