2 Creative Industries: A Sustainable Development Option for Small Legacy Cities

Aparna Katre

Context

There are, by some counts, around 400 small legacy cities in the USA. With populations between 15,000 and 110,000, these cities were incorporated before 1950 and have not experienced population growth since the 1980s. In their economic heyday they were America’s “hometowns,” romanticized in movies and literature.

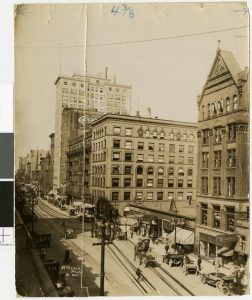

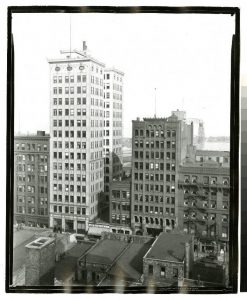

Duluth, Minnesota was one such city. In 1900, it was a bustling town in which life revolved around the steel industry. Blacksmiths and carpenters were automating their work, improving productivity through new machines, and helping erect buildings to address the population’s rapidly increasing needs. New technology and machines were being used to make large-scale farm fencing, improving the amount of nearby land that could be cultivated. This archive provides a history of the growing industrial town, including advancements in steel production and the supporting infrastructure for power generation, transportation, and packaging. It paints a picture of life in the community, where some 3,000 people were employed in early 1900, with its streets, stores, dentists, druggists, barbers, and tailors, and, for social gatherings, its clubhouse, neighborhood house, playgrounds, and churches.

- McKenzie, Hugh, 1879-1957. 1930?. “Aerial Lift Bridge: View of Superior Street Downtown, Duluth, Minnesota.” University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, Northeast. Minnesota Historical Collections. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/nemhc:4146

- McKenzie, Hugh, 1879-1957. 1923?. “Business district on Superior Street, Duluth, Minnesota.” University of Minnesota Duluth, Kathryn A. Martin Library, Northeast. Minnesota Historical Collections. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/nemhc:2317

In the late twentieth century, as major industries such as steel, tire, and automotive manufacturing moved offshore, core businesses in these small legacy cities began to close, causing both direct unemployment and the subsequent decline of businesses supporting the primary industries. Having depended on a handful of large companies for employment—like US Steel in Duluth—these cities experienced declining cultural and economic power. In subsequent decades, they experienced more boom and bust cycles. But while they remained stagnated, recognition was dawning that the wellbeing of these towns was essential for the wellbeing of their states and regions, and indeed for the prosperity of the country as a whole (Hollingsworth & Goebel, 2017). Small legacy cities are the economic and cultural hubs for their surrounding rural communities.

These economic shocks have revealed the need for a new development approach, one that leverages the special qualities of a place, its industrial history, and innovation ecosystems to create thriving communities. Economic activities rooted in the cultural, social, human, and natural capital of a place constitute its creative industries. These industries are resilient to external shocks, and they provide both more inclusive development and a path for revitalizing legacy cities (Unctad, 2010). In the last decade, several grassroots creative hubs and corridors have emerged in these small legacy cities around the country, creating a more diversified economic portfolio. In their book Our Towns, James and Deborah Fallows (2018) tell the creative industries-based revitalization stories of towns across the heartland of America, such as Columbus, MS; Asheville, NC; Duluth, MN; Fort Wayne, IN; and Holland, MI.

Challenges in harnessing the power of creative industries

Creative industries are leading the revitalization efforts in small legacy cities (see Main Streets of America). They have taken center stage at the global level as well, with 2021 being dubbed the “international year of the creative industries for sustainable development” (see https://tinyurl.com/y6ryrv7f).

For small legacy cities, however, the rise of creative industries is not necessarily associated with a city’s economic revitalization. Instead, in the economic discourse, arts, culture, and creativity-based initiatives continue to be perceived as ancillary. This lack of recognition of the contribution of creative industries to economic development can be partially attributed to confusion caused by the multiplicity of definitions (Cunningham & Flew, 2019). Some definitions prioritize intellectual property, others see the industries as limited to the core cultural arts often represented by arts and culture nonprofits, and others include festivals, heritage, tourism, and sports. To take center stage in economic development, creative industries must be given a locally relevant definition. In 2017, for example, Duluth’s Public Arts Commission introduced a strategy to develop a broader and more nuanced understanding of the creative economy in order to understand how arts, culture, and creativity play an important role in the city’s economy (Creative Watershed Report, p25).

I argue that current methods for communicating the socio-economic contribution of creative industries to small legacy towns, even if there is a commonly agreed definition, are inadequate. Creative Minnesota, for example, a website “developed by a collaborative of arts and culture funders and statewide arts service organizations in partnership with Minnesota Citizens for the Arts,” provides a visual and somewhat interactive representation of the contribution of Minnesota’s arts and culture sector. While the site allows for some drill down at the county and city levels, and provides some spatial characteristics, it has a few limitations. As it is limited to the nonprofit arts and culture sector, the economic activity it captures is only a subset of the contribution of all the creative industries. And the site does not address or convey the socio-economic revitalization of legacy towns and their approaches to issues of inclusivity and resilience.

Another report, the 2020 Lincoln Park Craft District case study, describes “homegrown” revitalization in Duluth through stories of businesses and through economic data such as investments made, number of businesses started, and number of jobs created. While valuable, this type of one-time case study can soon become outdated, and readers cannot drill down to explore the types of jobs created, the age and growth of the businesses, the creative sectors they represent, or the spatial and temporal characteristics of the creative endeavors.

Representations, reports, and case studies of this sort have limited influence on future investments. Where does one begin to exploit the power of the creative industries for sustainable development?

A proposed approach

The University of Minnesota Duluth has a Bachelor of Arts degree program in Cultural Entrepreneurship, with a focus on the creative industries. As program director and a principal faculty member, I have set a multi-year agenda to address above-mentioned issues through research and through community-engaged teaching and learning. The approach presented below incorporates learning from the first three years of this journey and in the context of the legacy city of Duluth, MN. Students in my Introduction to Creative Industries course have developed story maps to visually communicate the non-monetary contribution of Duluth’s creative industries, and tested them with community members for feedback. Working with Dr. David Wilsey and a team of students from the Masters of Development Practice program he directs, we developed a community toolkit to arrive at a localized definition and understanding of the creative industries. In collaboration with Ecolibrium3, a community development nonprofit, and with an undergraduate intern, we developed a framework to capture important economic data and visually represent the economic contribution of the creative industries. While work is still in progress, I believe these projects have helped develop a comprehensive methodology and toolkit that can enable legacy cities to answer the following questions. It gives them a jump start in bringing the creative industries to the forefront of the city’s economic development agenda.

- Has the city fully invested in all available aspects of its creative economy? Or is it focused on one sector more than others?

- Are there creative sectors such as sports and outdoors that are typically excluded by standard frameworks but essential for the local economy?

- How does the city measure economic and social contributions?

- How does the city ensure that related information is as current as possible?

- How can the city provide mechanisms for residents to interact with and understand the contribution of creative industries to local development?

We recommend a three-step approach to begin this journey:

- Community conversations to generate consensus about the definition of creative industries,

- Improved data definition and measurement methods, and

- Generation of interactive stakeholder-centered stories.

Community conversations

The Unctad (2010) creative industries framework needs to be contextualized while generating community-level agreement on creative industries’ constituting sectors. Markusen et al. (2008) emphasize that the ways in which contributors are included and excluded from the creative economy influence how that economy is understood, measured, and supported. We discuss an approach to conducting community conversations to identify and select the contributing sectors of the creative industries, accounting for their city-specific specialties and nuances, and share tools helpful in these conversations.

Even in a small legacy city, the process of holding conversations with diverse stakeholders and generating agreement about local creative industries can be daunting. Here you will find resources developed by us to facilitate community conversations. They help participants iron out differences of opinions about the creative sectors, their local relevance, and the types of businesses, nonprofits, and jobs that must be included or excluded when talking about creative industries for local development. The website provides a report to orient community members on current understandings of the creative economy. You can find templates to help you design marketing materials to invite community participation and set up logistics for the conversations to be held over a few days. We provide a guide to establish each session’s agenda and activities, preparatory materials for participants, and a guide for facilitators. A local nonprofit, university, group of city officials, or existing coalition working on developmental initiatives can serve as the anchor institution to drive planning and facilitate community conversations. The products from these conversations include documented understanding of the local creative industries and their sectors, important economic indicators, and a vision for moving the work forward.

Data Definition and Measurement Methods

Once your team consents to a local definition of creative industries, we propose the following measurement approaches, data collection methods, and important data elements.

America’s Creative Economy Report (2013) provides a good start to working with two key data elements: categories of creative goods and services, and creative jobs. We suggest using this list and your definition of the creative industries to build your list of creative goods, services, and jobs. The craft brewing industry, for example, constitutes a key part of Duluth’s creative industries. Breweries are therefore included in the culinary crafts sector, and craft brewer is included as a category in the list of job codes. Here is a list of creative goods and services we developed for Duluth, and another of jobs. Save copies and review the lists with the group helping define the creative industries. Add and remove entries to meet the local requirements.

Next, we suggest building a data dictionary to measure key economic indicators for the creative industries. The United States Census Bureau’s survey of business owners is a good starting point. We developed this version, accounting for nuances of creative industries such as nonprofit business structures, possibility of grant income, volunteer workforce, and the geographic spread of customers and suppliers to convey the spatial impact. We decided to collect the data using this online survey, creating key sections for general and legal business information, employment, financial, and geographic spread of customers and suppliers. Use them as a starting point for your city.

You can use this template to establish a baseline of the organizations, by neighborhood, that fit your definition of creative industries. We recommend that the anchor institution dedicate resources to collecting this data over a three-month period in the first year, and annually thereafter. In our experience, data collection works best if done through person-to-person contact, physically or virtually, rather than through emailing. Here is a draft of an email to help you start inviting business community participation.

Finally, we recommend generating descriptive stories for each organization characterizing the founder motivations, vision, and values and the organization’s contribution to the community.

Generating Interactive Stakeholder-Centered Stories

The impact of creative industries on your local communities can be presented along both economic and socio-cultural dimensions. Esri’s ArcGIS tool can be used to create several layers of visual maps telling a wide range of stories. You can work with an institution that has access to this tool, such as the local government’s economic development agency or a local university. Descriptive information about the industries’ goods and services, and about their contribution to community well-being, can be conveyed through story maps, which can tell sector-specific stories about the city’s history, culture, and natural and built environments, and about the industries’ benefits to the community. These maps can help answer the following questions:

- What does the creative economy of a particular post-industrial small legacy city look like?

- How does the landscape and the industrial history of the region influence the character of its creative industries?

- What are some of the organizations and people that constitute the area’s creative industries?

Making this data interactive helps motivate users to engage with the creative industries and learn about their breadth, depth, and strengths. The story map below, for instance, provides a sector-based visualization of the creative industries in Duluth. Interacting with the tabs, a user can see the sheer number of data points and the diversity of grassroots action in the outdoors, crafts, and culinary crafts sectors of Duluth’s creative industries.

A few engaged local viewers interacted with the story maps and observed that, while they knew the outdoor sector is very important in the region, there seemed to be a lack of local manufacturing to support the outdoor industry. Likewise, reading the stories of restaurants in the culinary sector, they highlighted the opportunity to think about more systemic connections between local farmers and restaurants.

Please note that these images are illustrative only and do not capture the entirety of Duluth’s creative economy.

Map layers can be customized to convey aggregated economic indicators such as sector-wise trade; the number of organizations by sector, employment by creative job type; the distribution of full-time, part-time and volunteer-based employment; the number of patents, trademarks and copyrights; and the geographical spread of customers, audiences, and suppliers. Furthermore, capturing the spatial distribution of these indicators can convey important information about the clustering of businesses and jobs by sector, as well as the geographic spread of employment opportunities, providing a sense of the extent to which businesses employ local residents and whether gentrification is arising from the growth of the creative industries.

The charts below, although preliminary and only partially complete, show how maps can present economic information to convey important insights.

Charts and graphs can be displayed dynamically in the story maps using the latest data. One can, for example, create a visualization for aggregated economic indicators such as the top five creative jobs in the city, the share of businesses by their size (revenue), and the top sectors by revenue and employment. The charts below show a subset of Duluth’s creative industries as of December 2019, and were developed to show the importance of using interactivity and drill-down capabilities to convey economic indicators.

Conclusion

The creative economy is a significant contributor to the broader economy in terms of GDP, employment, and growth opportunities. It has demonstrated resilience to economic vicissitudes, fosters inclusive development (Unctad, 2010, 2018), and can help revitalize the economies of post-industrial communities, cities, and regions (Markusen & Gadwa, 2010). It is proving to be an emerging and robust economic sector, strengthened by emerging technologies, and it can be the basis of the creation of entirely new industries. With the right investments and policies to support the growth of local creative industries, cities can facilitate economic resilience and overall wellbeing of communities. We have provided a framework for understanding, capturing, and conveying the impact of creative industries in small legacy cities. We hope this will help address the needs of those working to advance the agenda of creative industries for sustainable development of their towns.

References:

America’s Creative Economy Report (2013). Available at https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Research-Art-Works-Milwaukee.pdf

Cunningham, S., & Flew, T. (2019). Introduction to a research agenda for creative industries. In S. Cunningham & T. Flew (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Creative Industries: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Fallows, J., & Fallows, Deborah. (2018). Our towns : A 100,000-mile journey into the heart of America (First ed.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Hollingsworth, T., & Goebel, A. (2017). Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities: Strategies for Postindustrial Success from Gary to Lowell: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Markusen, A., & Gadwa, A. (2010). Creative placemaking: National Endowment for the Arts Washington, DC.

Markusen, A., Wassall, G. H., DeNatale, D., & Cohen, R. (2008). Defining the creative economy: Industry and occupational approaches. Economic development quarterly, 22(1), 24-45.

UNCTAD. (2010). Creative economy: A feasible development option: UNCTAD.

UNCTAD. (2018). Creative Economy Outlook and Country Profiles: Trends in International Trade in Creative Industries: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. David Wilsey, Program Director, Masters of Development Practice (MDP) and his students in the program helped develop the toolkit for the community conversations. A summer intern supported by Ecolab Scholarship and the Institute on Environment helped frame the data design and assisted with data collection and the development of aggregate information. Ecolibrium3, a Duluth nonprofit, was our community stakeholder and encouraged participation from local creative businesses. Students in the CUE 1001 Fall 2019 and Spring 2017 courses at UMD helped collect the data, create the stories, and develop the two story maps presented in this article. Finally, the consultants at UMD’s Geospatial Analysis Center provided the technical assistance for the entire project.