5 Guardians of Cleveland

Beth Mercer-Taylor

As the Sustainability Education Co-Director at the Institute on the Environment (IonE), my work supports sustainability learning and projects of University faculty, staff, students and community partners. In 2008, I got the job of shepherding the communities of faculty and students connected to the Sustainability Studies Minor, a new UMN program drawing on the expertise of faculty from many departments. My interest in, and even my awareness of, the concept of sustainability began only shortly before I started the job. The minor continues to immerse students in interdisciplinary, real-world approaches to sustainability, using “systems thinking,” a method of holistically understanding how a system’s constituent parts interrelate over time and in a broad context. The curriculum now incorporates environmental justice and indigenous knowledge systems as well, a result of advocacy by students and the community.

Since sustainability education was brand new when I started, many faculty and staff like me spent time, alongside our students, learning how human and natural systems interconnect. Since I had not studied sustainability, climate, change or environmental science, it was eye-opening for me to read books that have shaped the sustainability field, like Limits to Growth, Resilience Thinking, and Cradle to Cradle, and to attend conferences with colleagues across the US, all of us trying to nurture our nascent academic sustainability programs. I came to understand sustainability as being intertwined with justice. And although I had failed to recognize it earlier, I came to see that my early concern with inequitable social systems, and my connection to sustainability, had both begun decades ago when I was growing up in Cleveland, Ohio.

Cleveland— From Superhero to a River on Fire

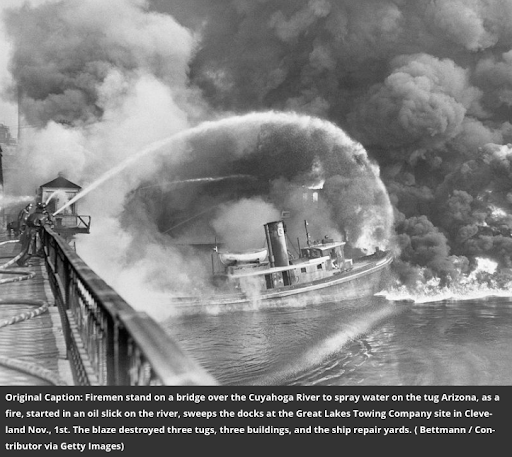

I was born in 1968 in the Rust Belt city of Cleveland, before steampunk made that sound cool. Through my childhood in the 1970s, my city was derided by latenight host David Letterman, and others, as the “mistake on the lake.” These insults called upon an iconic image of the Cuyahoga river burning near its outlet into Lake Erie, as featured in Time magazine on June 22, 1969.

Cuyahoga means “crooked river” in Iroquois. It is a 100-mile-long river starting in rural eastern Ohio and winding through Akron and Cleveland, picking up sewage and industrial waste on its way. Even as a suburban kid from Shaker Heights, I found the Cleveland jokes personal. The city’s challenges were big and obvious: industry caused pollution, as well deindustrialization, job losses, depopulation, vacant buildings, poverty, and fewer city tax dollars to use on more problems.

Redlining, a common phenomenon in which realtors would not show homes in predominantly White neighborhoods to Black families, combined with increasing income inequality, contributed to making Cleveland a highly segregated city. In the late 1960s, many Whites and some middle class Blacks moved out of East Side neighborhoods into new suburbs. As the percentage of poor Black residents on the East Side increased, residents faced higher rents, decaying buildings with little code enforcement, erratic garbage pick-up, and vermin. Disparities were made worse by police, who were often aggressive towards Black residents, especially youth, and slow to respond to calls. East Siders lacked easy access to jobs in the suburbs. The Cleveland jokes made it seem like we Clevelanders caused our own problems, but for those of us living in or near the city, it was obvious that larger forces shaped our destiny.

Cleveland was once the fifth-largest city in North America, and one of the wealthiest. Superman, the man of steel, was birthed in Cleveland (home of his creator) in 1938, at the advent of the city’s industrial rise. Industry still exists—the Cleveland-Cliffs company, for instance, operates its steel mill on the Cuayhoga’s shores, employing 1700 workers—but many of Cleveland’s titans of industry left or downsized during the 1960s, including Sherwin-Williams Paint, Standard Oil, Republic Steel, and American Ship Building, along with the smaller companies that served them. The industrial facilities that were shuttered and the jobs that were eliminated were never replaced.

Cleveland has steadily lost population. When I was born in 1968, there were approximately 750,000 residents, down from a peak of nearly a million in the late 1950s. Between 1960 and 1980—encompassing the years of my childhood—Cleveland lost 35% of its population. I remember boarded-up office buildings and once-iconic department stores downtown, and vacant blocks on the East Side, where fires and the failure to enforce building codes led to tear-downs during the 1970s. In 1978, Cleveland defaulted on loans and teetered on the edge of bankruptcy, as Mayor Dennis Kucinich failed to convince local banks to restructure loans to allow Cleveland to make payments and serve residents. Cleveland did gain jobs in health, education, and the service sectors during the 1980s, and successfully retained some manufacturing, but could not stem its outmigration. In 2021 the population is now just 380,000, making Cleveland the 53rd-largest city in the US.

The 1969 Cuyahoga fire, the butt-end of Letterman’s jokes, was the last of several fires that came to symbolize the failures in Cleveland. In July 1966, during an uprising aimed at destroying White-owned businesses, flames rose in the predominantly Black East Side Hough neighborhood. What the press termed “riots” were nominally triggered by a White bar owner refusing a glass of water to a Black resident, contributing to an atmosphere of mounting frustration.No real improvements followed the Hough riots, and flames rose again in July 1968 in Glenville, another predominantly Black East Side neighborhood that had been an early upscale bedroom community (and birthplace of Superman’s creator). Tensions had mounted in Glenville as police monitored and harassed those they determined were Black nationalists, culminating in a shootout that killed seven, followed by fire and destruction.

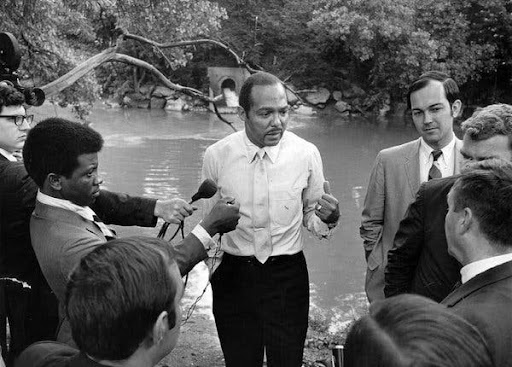

In comparison to the Hough and Glenville fires, the infamous fire on the Cuyahoga River in 1969 was quite small. It was sparked by a load of iron ore on a railroad bridge, and put out quickly with no buildings lost. The Time photo accompanying the story about the fire was from a much bigger conflagration on the Cuyahoga that caused 1.5 million dollars in damage in 1952, when there was more industry and more pollution. Some surmise that the 1969 Cuyahoga fire became a story only because Time reporters were in Cleveland to cover the first Black mayor of a major US city, Carl Stokes, elected in 1967. Undaunted by the possibility that he could be blamed for an oil-slicked river catching fire, Stokes capitalized on Time’s coverage to Cleveland’s advantage.

Looking at Cleveland’s fires through the lens sustainability, I see them as catalyzed by economic, social, and environmental policies designed to foster industrial growth and prioritize the interests of middle-class Whites and the White-led business community. As the city shrank, the policies that had once made Cleveland grow could were not helping the people or the environment. Because racism was so embedded in the way the city worked, predominantly White neighborhoods in Cleveland, and in adjacent, predominantly White suburbs, benefited from better infrastructure maintenance and more regular city services, like recreational opportunities and pollution clean-up, compared to predominantly Black neighborhoods. The same kind of structural racism underlying Cleveland’s governance has been mirrored since then across the US, exemplified most starkly in Hurricane Katrina’s aftermath, with devastating losses of life and property that were heavily concentrated in New Orleans’ poorest, predominantly Black neighborhoods, where levee infrastructure had been neglected for years. Devastation for Black city residents of Cleveland has been just as real, even though it has unfolded more slowly and out of the public eye. Deindustrialization had harmed poor and Black city residents the most, but Cleveland’s Black political leaders, like Mayor Carl Stokes, knew what was going on and pursued a strategy that would start to direct resources towards improving people’s lives.

As I was growing up, I didn’t see social justice and the environment as interconnected; rather, I saw the two as either/or. By the time I was a teenager, I had a negative feeling toward environmentalism, seeing it as benefiting people with resources to enjoy far-away places like national parks and wilderness, and not focused on life in cities. But I did know early on about the river fires and clean-up efforts. This was one of the first times in my life that felt sad and angry about something beyond my family. I also remember seeing, maybe years after its publication, Time’s famous 1973 Minnesota Miracle cover, with a healthy fish held up by a smiling White man I now know as Governor Anderson, and thinking how lucky it was for people to live in what seemed an unspoiled place. Had I grown up in another place, my day-to-day activities might have led me to think of myself as an environmentalist. I spent lots of time outside in my backyard or in the wooded parks that gave Cleveland its early nickname of “Forest City,” got around on my bike or by rapid transit (light rail), planted a garden, and often fixed things with my mother—who liked to tell me “waste not, want not.” I did not think deeply about my privilege to go outside in pleasant green spaces. While I was aware of global warming and renewable energy as good solutions, the issue seemed far off. By high school, I saw poverty and racism as the biggest problems in society, and thought that to stand up for people and to work to undo racist practices, I should pursue civil rights, community organizing, and urban policymaking. Not realizing it at the time, I was influenced by the way Carl Stokes prioritized people, and East Side Black residents particularly, in his leadership in the aftermath of Cleveland’s fires.

Carl Stokes: Sustainability advocate ahead of his time

Motivated by Cleveland’s fires and what they represented, Mayor Carl Stokes became a pioneer of sustainability advocacy as he insisted that environmental cleanup must benefit the people living in that environment. He used his celebrity to make people see that the Cuyahoga fire indicated an urgent need for holistic change in both social and environmental conditions in Cleveland and other industrial cities.

Stokes chose to embrace the city’s problems rather than blame prior leaders for them or explain them away. One day after the fire, Stokes took a press entourage on a four-stop tour to see pollution sources: a broken sewer intercept leaching raw sewage, the chemical-soaked railroad bridge where the fire started, a chemical plant on the riverbank, and an open sewer pipe with its contents pouring into the river. He told reporters that the $100 million bond initiative he had supported to clean up the river, passed just a year prior, was simply inadequate to the scale of the problem. Stokes explained that other suburbs and nearby cities—not Cleveland alone—were responsible for the sewage and waste flows. Businesses, like the chemical plant on the tour, had clearly abdicated responsibility.

After emphasizing Cleveland’s need for cooperation from entities outside its control, Stokes filed a complaint with the state of Ohio, seeking assistance. The state had done little to ensure the welfare of Clevelanders, to even minimally regulate industry, or to ensure safe waterways. Getting no results from the state, Stokes then tapped his political network to bring the need for funds for Cleveland, the river, and Lake Erie to Congress. Carl and his brother, Rep. Louis Stokes (D-OH), testified in support of federal legislation that would ultimately put dollars towards that cleanup. Stokes’ testimony led to the Clean Water Act and the authorization of the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in December 1970. At the inaugural Earth Day event in April 1970, Stokes said “I am fearful that the priorities on air and water pollution may be at the expense of what the priorities of the country ought to be: proper housing, adequate food and clothing,” For him, the people’s environment was the environment as a whole.

The fires and their aftermath symbolized deep social and environmental challenges simultaneously facing Cleveland and many other deindustrializing cities. The Hough and Glenville fires sparked debate about social justice issues, racism, and structural inequities, and Stokes offered solutions through public-private city revitalization and anti-poverty programs. He also worked to change the composition of the city’s police department and the city staff, so that the experiences of Black residents and of women would be represented and the problems of racism and sexism brought to light. When the Cuyahoga river fire sparked debate about the environment and pollution, Stokes used that window of opportunity to convince other political leaders that the scale of the problem was state and national, requiring funding for Cleveland, not just from it.

Stokes capitalized on the Cuyahoga fire and the attention of journalists, politicians, and business leaders, shining a light on the conditions of Cleveland’s Black residents and working to direct state and national economic resources to the city’s aid. Through the Cuyahoga fire, Stokes framed the problems his administration faced as larger than Cleveland or Cuyahoga County—he saw how everything connected. He understood cities as systems, across scales of time and geography, and saw leverage points that could create change. Stokes pursued a “sustainable development[1]” agenda years before sustainable development was commonplace.

When Stokes was elected in 1967, a year after the Hough riots the Voting Rights Act was two years old. More Black Clevelanders could now vote. He drew strong support from two very different constituencies. He rallied Black voters, who comprised about 40% of the city’s voting population, by promising to stop the neglect of Black community needs. And he negotiated support from key White political and business leaders, who sought stability on the East Side. Stokes used his relationships across the city to keep things calm in the spring of 1968 after the Martin Luther King, Jr. assasination led to violence across many US cities.

But the summer then grew tense as police engaged in racial profiling and oppressive practices on the East Side, which Stokes could not control, and which led to the Glenville shootout. As a post-shooting de-escalation tactic, Stokes pulled White police officers out of Glenville, leaving Black officers to patrol in the neighborhood. While no one died after the shootout, perhaps as a result of that decision, Stokes was criticized for the property destruction that occurred. In addition, one of the convicted shooters, Fred Ahmed Evans, was found to have bought guns using city money provided by a Stokes program called Cleveland Now, which had a mission of neighborhood revitalization. Despite his deep understanding of Cleveland’s problems and the sustainable solutions he envisioned, the Glenville shootout was the end of his political career. While Stokes would squeak through to win his second mayoral election in 1970, he did not run for a third term, and left Cleveland to become a New York City journalist in 1972. He stayed in contact with his Cleveland roots, returning as counsel for the United Auto Workers in 1980 and becoming a municipal judge in 1983. While Stokes had prescient ideas to solve systemic problems in Cleveland, the racism within the system – in form of the city’s police practices – took away his chance to fully implement those ideas.

Epilogue

I am grateful to the IonE Educators for telling their stories and providing me the impetus to better understand the origin of my own negative feelings about environmentalism. Hearing their reflections about their sustainability watersheds, and learning what they valued about the places they came from, put me on the path of wanting to learn more about Cleveland and, ultimately, sparked my curiosity about how my views on environmentalism were shaped by my youth in Cleveland. This led me to the political philosophy of Carl Stokes, which I realized had influenced me so profoundly. Though I was a preschooler while Stokes was the Cleveland Mayor, I was aware of his importance —his name is all over Cleveland’s buildings and cultural life. His legacy was also alive in the teachers and community leaders who shaped how I saw cities, and community and planning efforts, and how I always want to ask who pays and who benefits. I became a skeptical environmentalist. But I hope my students will learn from the example of Carl Stokes and become proponents of holistic sustainable development that prioritizes human needs. And I hope more of my faculty and staff colleagues will see the world as clearly Carl Stokes.

My experience led me to believe that sustainability is for everyone. If we are going to fix the multiple and complex ways the world is becoming less livable for humans and our fellow creatures on the planet, we need many hands and many ideas. I tell University of Minnesota students that, as a lawyer and policy analyst, my own training is in how humans shape- and harm – the environment. Understanding how human institutions work offers great preparation for the sustainability work of changing our systems. It is not necessary to be a scientist, or to have deep environmental knowledge, to contribute. One former student, now an organizer at the Sierra Club, majored in Youth Studies and took only a couple of classes related to the environment. She mentors people and keeps teams working well together. My grandparents didn’t need college degrees to understand how to live frugally in their mobile home, cultivating a garden and fruit trees, staying close to home, and keeping things working instead of buying new. Like low-income people around the world, they knew how to make the most of the things they had. Meeting the needs of present and future generations at the same time requires a focus on so much more than the environment.

A poem tells the story another way.

River on Fire[2]

by Cleveland poet Dave Lucas

Stranger, the way of the world is

crooked, and anything can burn. Nothing

impossible.

Who comes to send fire upon the earth

may find as much already kindled, may find his

city bistre and sulfurous. Pitched and

grimed.

On those suffered banks we sat down

and wept.

There the prophets, if there had been

prophets, would have baptized us in fire.

Who says impossible

they fill his mouth with ash, they quench him

as if a man could be made steel.

A crooked way

the world wends, and the rivers,

and the prophets.

Go down and tell them what you have seen:

that the river burned and was not consumed.

Resources

The Myth of the Cuyahoga River Fire

How Ohio’s Cuyahoga River Came Back To Life 50 Years After It Caught On Fire

Lake Erie and the Cuyahoga River Fire — 50 Years Later

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHlqvaq0Q9k

https://travelingstanzas.com/educators/river-stanzas

http://www.clevelandmemory.org

https://www.nps.gov/articles/carl-stokes-and-the-river-fire.htm

David and Richard Stradling, “Where the River Burned: Carl Stokes and the Struggle to Save Cleveland”

Carl and the Crooked River: The Making of an Environmental Mayor

- Sustainable development was defined by the United Nations UN Brundtland Commission in 1987, in Our Common Future, a report published by the World Commission on Environment and Development. “Sustainable development,” in the UN definition, is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” ↵

- Poem reprinted in https://www.toledoblade.com/a-e/2018/10/21/poetic-world-we-live-in-dave-lucas-cleveland/stories/20181014005 ↵