6 Listening to a Four-eyed Fish: Uncovering the Mysteries of Atlas Limina, the Map of Thresholds

Kimberly Byrd

Prelude: This is a story of a deep journey, one that began with my work at the Institute of the Environment drafting a new sustainability class for the University of Minnesota. In true inner/outer, the personal-is-political feminist epistemology, the voyage integrated with my internal landscape in a time of great change and growth. Sometimes I would feel confusion, bewilderment, or disorientation in my own life, but I could perceive where I was on the map I was creating for class. I saw that I needed to live the journey before I taught about it. Here is the story of that journey so far.

Act One: Close Encounters of the Third Kind

I created all of the images in this chapter. Many began with my original photographs or with photographs freely available on Unsplash. I digitally altered these images in an iterative fashion, sometimes using multiple apps.

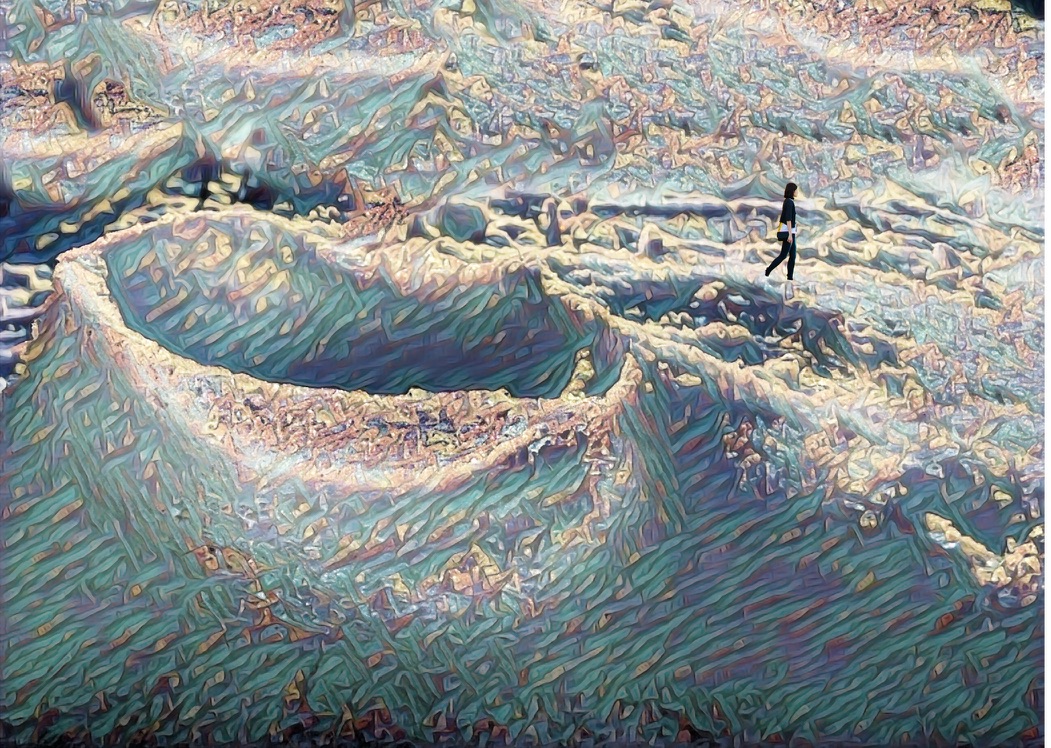

Everywhere around me, I saw basins. The cup of a plant, tufting in the sofa. I was the crazy lady who jumped out of her car on the way to the dentist’s office to get super close-up macro pictures of holes in the sidewalk. At one point, frustrated with not finding the perfect image, I placed tiny cups all over the kitchen counter, put a wet sheet on top, and tried photographing that. It was a disaster. Architect-husband said, “You know, you could make the basins out of mashed potatoes, and then you’d be just like the guy in the movie sculpting the Devil’s Tower.” He was right. I was in too deep.

Something was calling me, and I was figuring it out in a way that was far different than how I had figured things out in the past. My usual MO was to think, and think, and think, and do more research. This was something different entirely. The basins had captured my imagination, and I was working it out in there. Maybe I was in just deep enough.

I had a career studying worldviews, crawling into people’s perspectives and telling their stories from the hero’s point of view. I understood the power of paradigms, and how they shape what information we take in and the ways in which we make sense of it. I strove to see each worldview from the vantage of non-judgement.

At the time when I started to see the basins, I was drafting an introductory sustainability class for all incoming freshmen at the University of Minnesota. Shortly after, I was asked to prototype a class that was already approved at St Thomas, “Social Science Research Methodologies for Transformative Sustainability.” I used the UMN framework as a starting point, and I had a class size of exactly one student. Things were proceeding…unusually. “I’m not quite sure what’s happening here, we’ve just got to let it unfold,” I told Matthew, my eager and imaginative St. Thomas student. I trusted that the project had its own process, and we were just along for the ride.

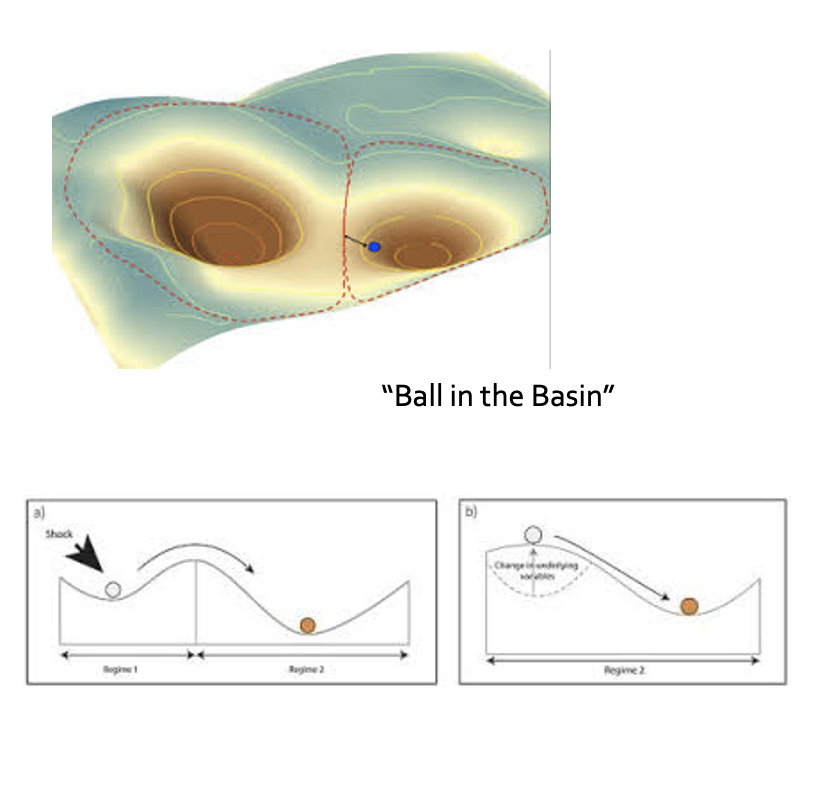

For more than a decade, I had been teaching about social-ecological resilience using two primary theories, Buzz Holling’s Adaptive Cycle (see more here) and the “ball-in-the -basin” model (e.g., Crepin et. al., 2012). I had long assumed it was easier for students to understand the Adaptive Cycle, but my University of Minnesota spring 2020 students told me otherwise. They preferred the ball in the basin. What?? I started thinking differently, concentrating on the model that had always seemed arcane to me.

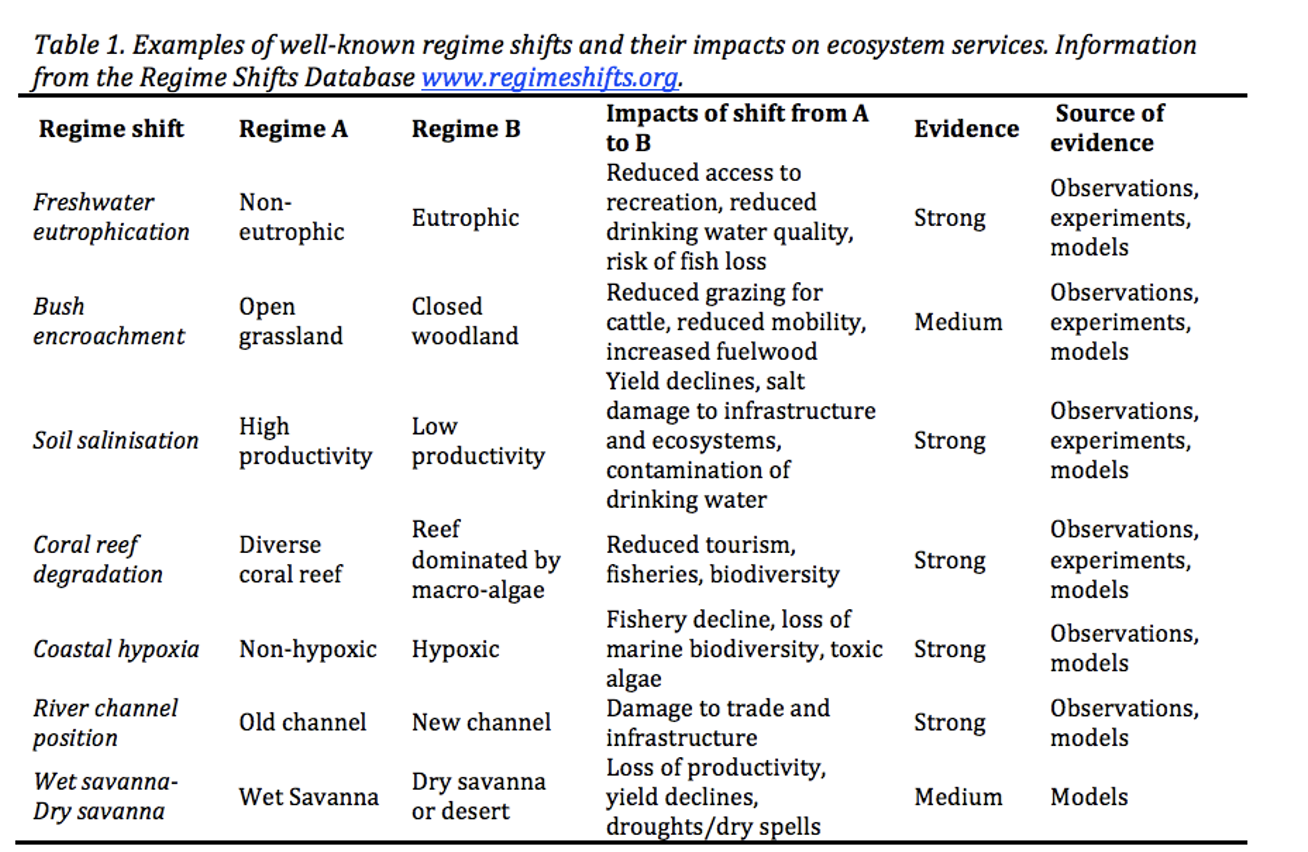

Like the Adaptive Cycle, the ball-in-the-basin model represents dynamic paths of change in social-ecological systems. In this model, the ball represents the current state of a system, and the “basin of attraction” is an equilibrium state that the system is drawn to because of feedback mechanisms within the system. Because the system’s external conditions are always changing (nutrient levels go up and down, political states become unstable, social fads drive an increase in certain types of consumption, etc.), so too is the shape of the basin. Multiple stable states of equilibrium likely exist for any particular system; the model can show how much a basin can change before it shifts into a new state of equilibrium or stability (basin of attraction).

As I developed my new class, I began to combine the basin theory with my understanding of worldviews and the fundamental paradigms that order our perception and decision-making.

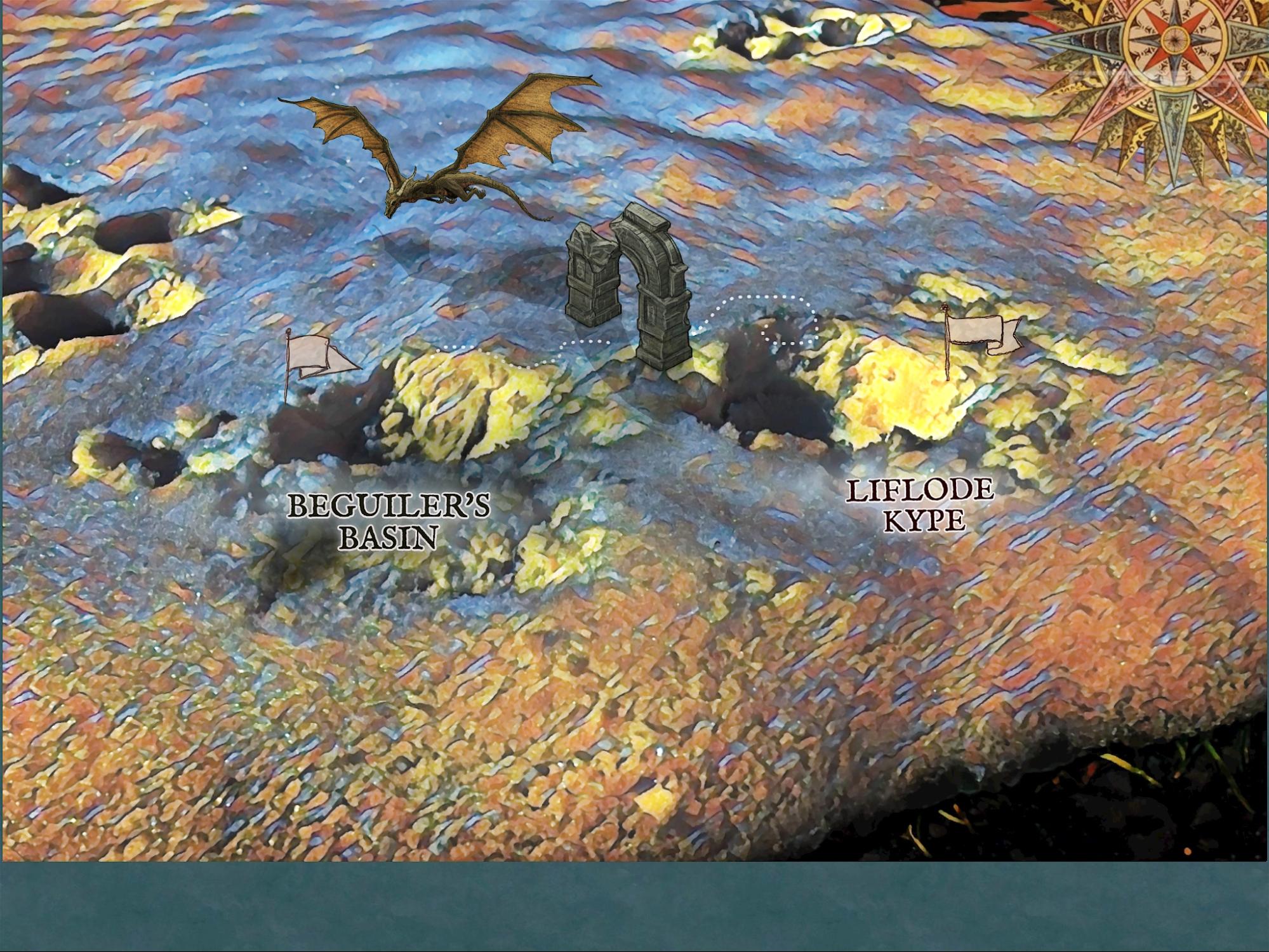

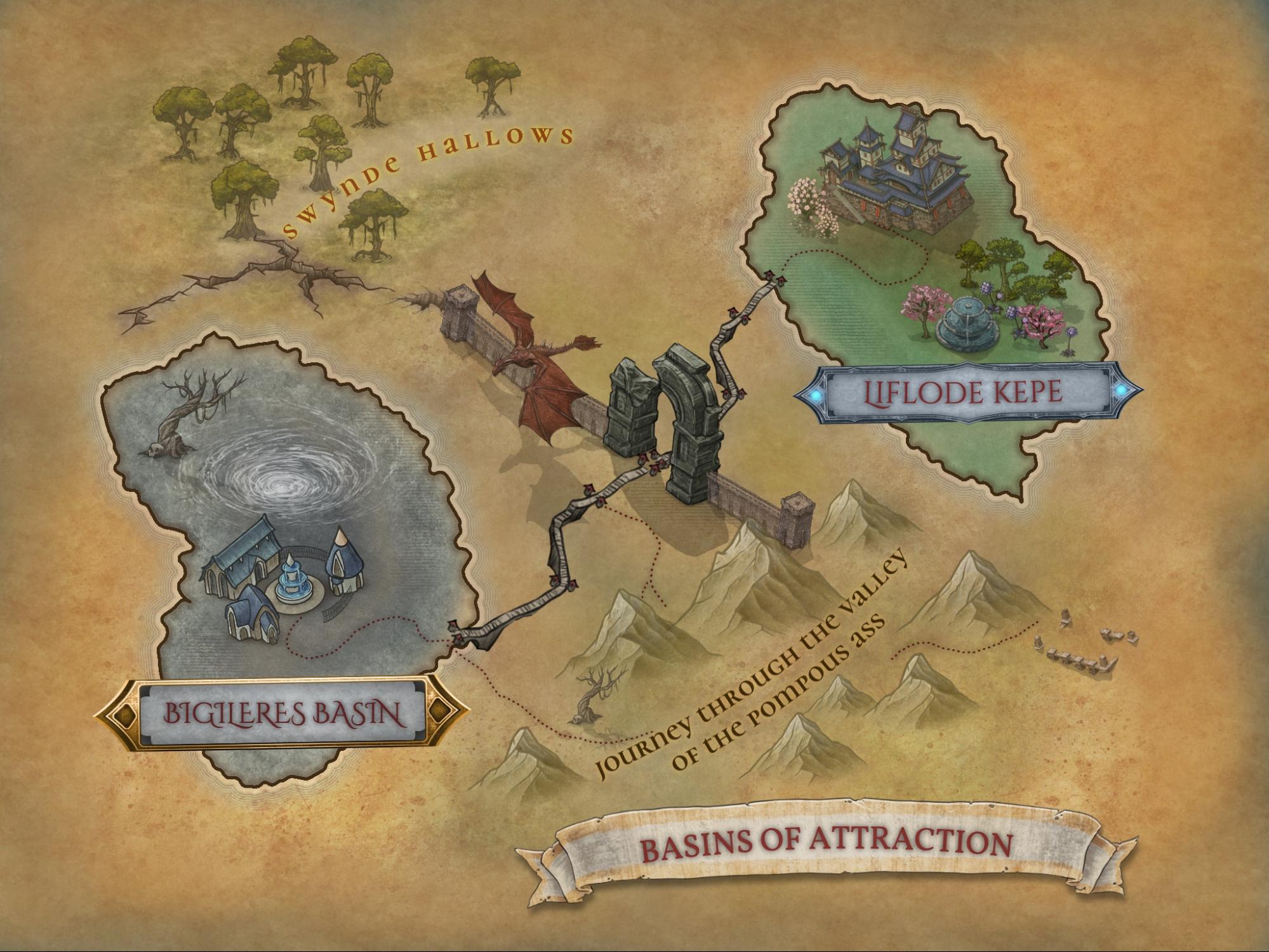

The ball-in-the-basin story of thresholds and regime shifts started to appear to me as a mindset journey from what I called a “Beguiler’s Basin” to the more life-affirming worldview of the basin I called “Liflode Kype,” or sustenance in life. Essentially, I began to see the basins as representing two different mindsets: one of limiting self-delusion and another that is more life-supporting, established from principles of ecology and core sustainability knowledge.

It was about halfway through the St. Thomas semester that I realized, “Ooooh no. no. no. To teach this well, I have to travel from basin to basin myself.” I had no idea, however, what that really meant.

Act Two: Epistemic Entryways

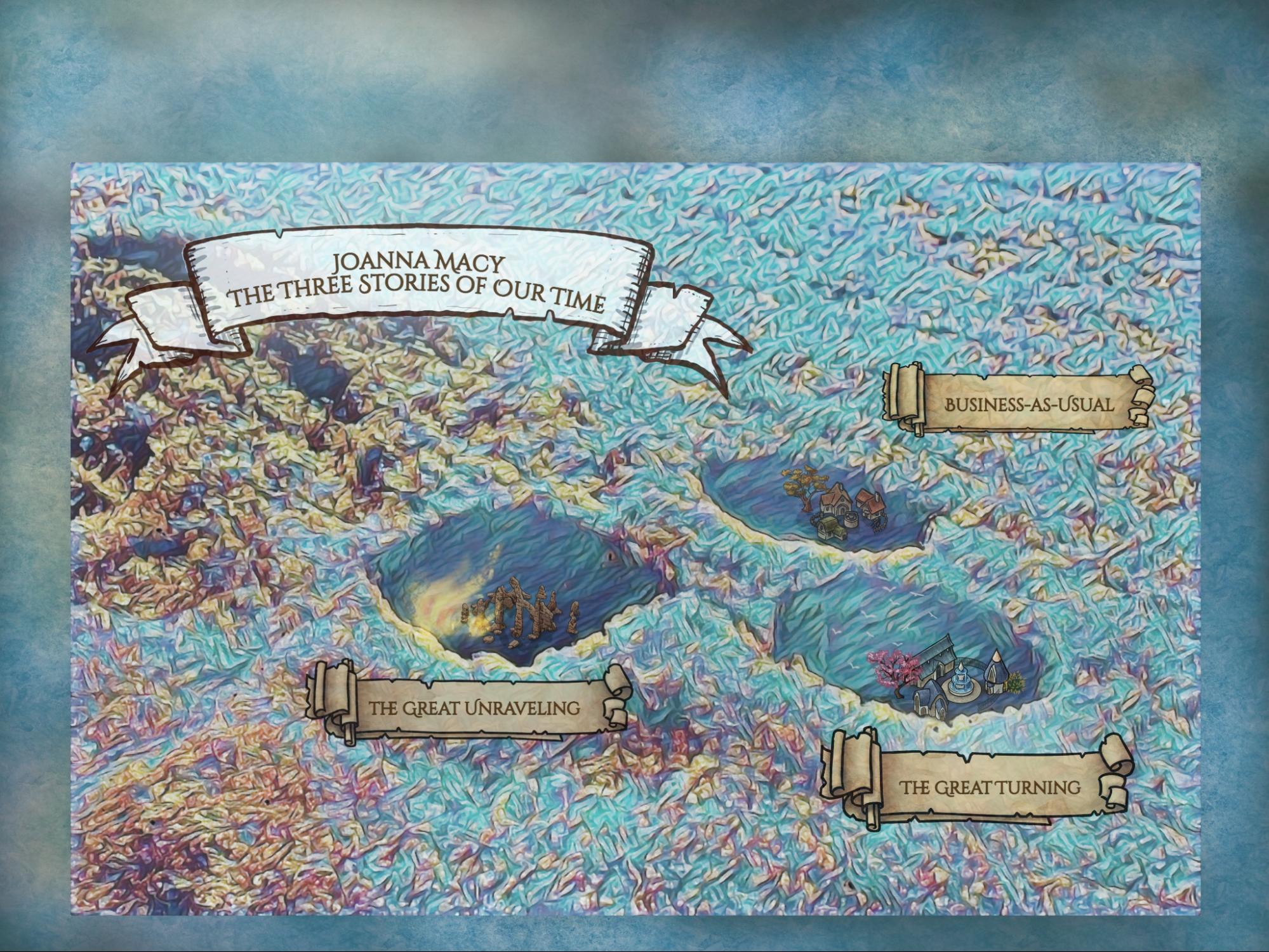

I had always been drawn to narrative analysis, the study of myth, and examinations of the power of stories in everyday society. For my Ph.D., I interpreted perceptions of wolves in Minnesota as stories or narratives, complete with heroes, villains, insiders/outsiders, sanctioning agents, and depictions of the good life for each. I admired the narrative approach of Joanna Macy (a Buddhist and systems thinker) and her three stories of our time: Business-as-Usual, The Great Unraveling, and The Great Turning. In the Business-as-Usual story, everything is pretty much fine, and things will work themselves out. In the Great Unraveling story, we are living in an apocalypse and things are horrific. The Great Turning story, by contrast, tells how people worldwide are expanding their knowledge and compassion to move towards a new relationship with the planet and with each other. On any given day, each of us may move from story to story.

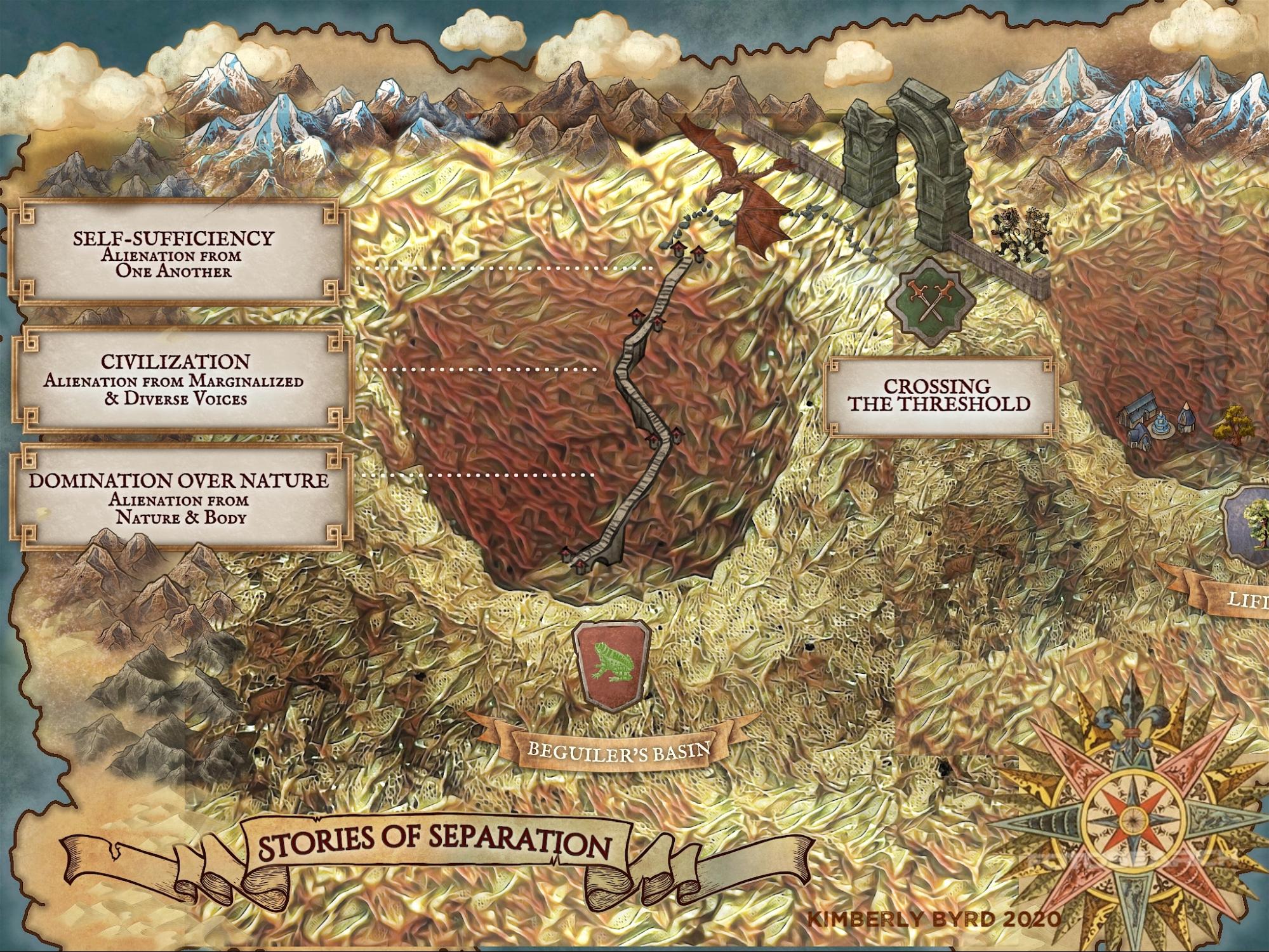

But I was especially entranced with Culture of Radical Engagement (2016), from The Relational Center (a California group providing leadership training for community builders, scholars, educators, students, caregivers, and healers from diverse fields). Their strategic story-circle framework detailing “Stories of Separation” utilized social capital research, social neuroscience, community organizing theory, radical relational theory, and somatic education to develop resonance and reclaim humanizing values through community. The Center identifies identify three cultural stories—humanity’s separation from nature, community’s separation from marginalized voices, and the alienation of our own selves—which became the basis of my passage through the Beguiler’s Basin to the Basin of Liflode Kype. The dehumanizing Stories of Separation in the Beguiler’s Basin illuminate how dominant systems divide and wound people, and how they estrange us from our bodies, from the earth, and from our fellow human beings. The Basin of Liflode Kype contains three Stories of Interbeing that explore justice, interdependence, and reciprocity. I could begin to see the stories of separation within myself.

As I started to cross-examine my approach for this new class, I questioned myself, and self-doubt (an old friend of mine) settled in.

Why can’t /won’t I do it the way it’s always been done?

Do my enthusiasm and curiosity fit in with traditional academia, a path I had turned away from, but was now reliant on?

As I reflected on my own life, I could see rebellion and a deep struggle to do things differently and take a remote path. My desire for adventure had been expressed long ago, when I asked to leave home to attend an international school for my junior year of high school, or ventured to trek for 30 days in the Wind Rivers and the Arctic Circle. It was also expressed by my choice of methodology for my Ph.D. project, by choosing to teach about wolves and othering, and even by the fact that I wore lipstick and dresses when everyone else in my conservation biology program wore flannels and hiking boots.

I knew there couldn’t be one single path to environmentalism or to caring for the natural world. “The frontier is long,” said Michael Soule, a founder of my academic field. We need all gifts and expressions to create the future we desire. Throughout my personal and academic life, I was striving to clarify and translate the deep respect and humility required to understand another’s journey.

The experience and interpretation of multiple narratives also appear in my teaching of sustainability. I help students uncover the diverse ideas about and definitions of “sustainability” that exist simultaneously, even within a single university class. To facilitate this, I assist students in the use of Q methodology, a hybrid quantitative-qualitative research technique that reveals collective stories or narratives that contextually exist around a topic of interest. I used this method in my dissertation; in the classroom, my students use it to study themselves. This process of “standpoint clarification” (Lasswell) has been eye-opening for many of my students because it reveals different ideas of change and agency. “Oh…that’s why I’ve been fighting with Aunt Martha for 10 years,” exclaimed an undergraduate student a few years ago. “I think deep social transformation happens as a result of organized social movements, and she thinks it happens because of market dynamics.”

But lately, things had taken an interesting turn, and I wondered where I fit in. Where did I belong? What was I to do with the poetry and art that came out of my meditative practice? Between the Sanskrit mantras and the sitar, images and stories appeared, sometimes surprising, sometimes fantastical. When I made voice recordings of journeys immediately after my experiences, they came out as poetry.

Nothing before had felt so me, and at the same time so freeing of myself. Going into the roots of trees, feeling frog eggs in my shins…it was all very deep ecology/de-centering of self/Joanna Macy and the “holonic shift.” But was I living an illusion? Was this just me and my ego trying to be different again, to stand out somehow? Was it a trickster story?

I was exploring different ways of knowing—epistemic entryways that had more to do with knowing, experiencing, and being than with thinking. I journeyed through my meditations, but also through music. I saw the Honeydog’s 10,000 Years as a passage across a sustainability landscape I was beginning to imagine. I could feel it all, the great emotional journey, through this album. I played it at full volume over and over. And why shouldn’t I have feeling about all of this—this mess, the destruction, our hubris, and also our capacity for human imagination? How could I hold the grief of this human journey? How could I embody the knowing without collapsing? The music unlocked something within me I had tried to keep at bay all these years. It gave voice to the suffering and the sadness. Someone else knew this journey. I could feel it in my bones.

Ticker tape comes down/ They’re melting their toys down / for the war effort / all the kids are standing in line to enlist

Were the heavens standing blindly / or were they watching, full of rage?

You can’t punk me for too long / what happened to our dear sweet boy? / he don’t live here anymore

Act Three: Receiving the Gift

I never really doubted what I was here on earth to do. It was deep within, where my meditation journeys were embedded. From my movie-making experiments when I was 12, to my undergraduate activism, to my 14 years of teaching environmental ethics and sustainability, I thought I knew my calling. I saw a future that was possible, exciting, and joyful. I could help pull it out of students, and they helped pull it from me.

When I closed my eyes and thought about a new world, I saw a world where artists and storytellers helped reveal the role of feedback loops on our planet, making them immediate and direct instead of distant reckonings far from the horizon. I saw a world where we measured well-being with multiple capitals instead of the mono-capitalism of GDP and the “bottom line.” Education was revamped to focus on heart, soul, empathy, compassion, and imagination (see r3.0; Orr, “What is education for?”). In this world, youth, women, and indigenous peoples played a leadership role, teaching us different ways of knowing and experiencing. We were much better at imagining solutions because we embraced an integrated process of thinking and problem-solving. University departments were dissolved, silos abandoned, and a generative experience of mind, heart, and body guided us forward.

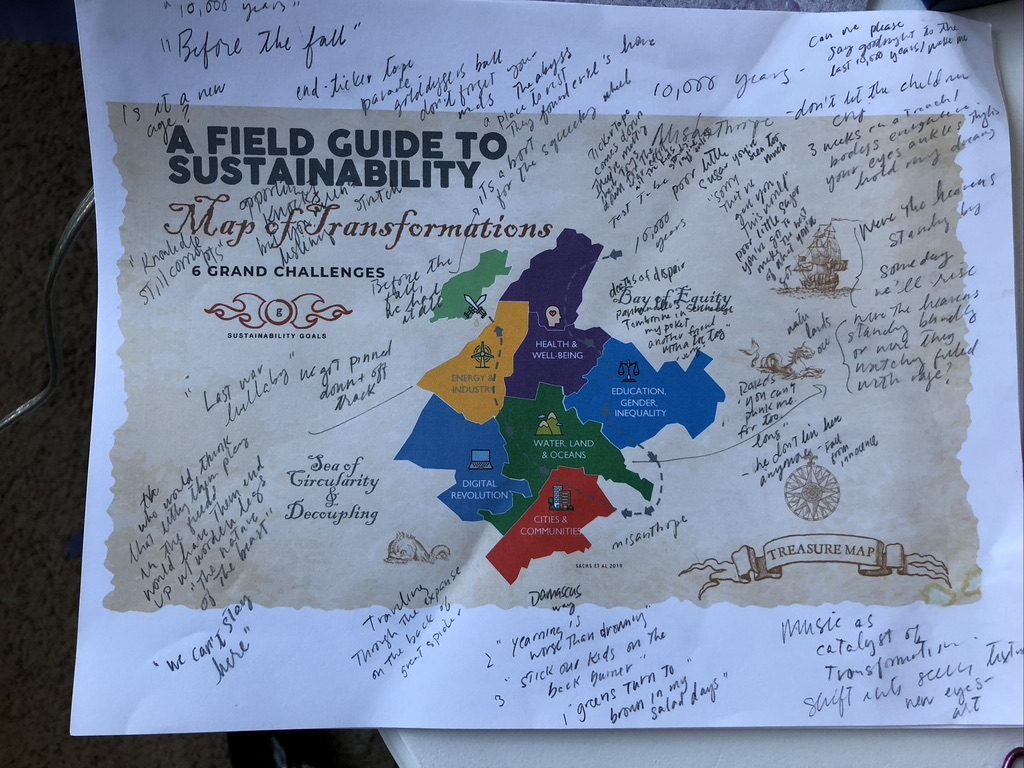

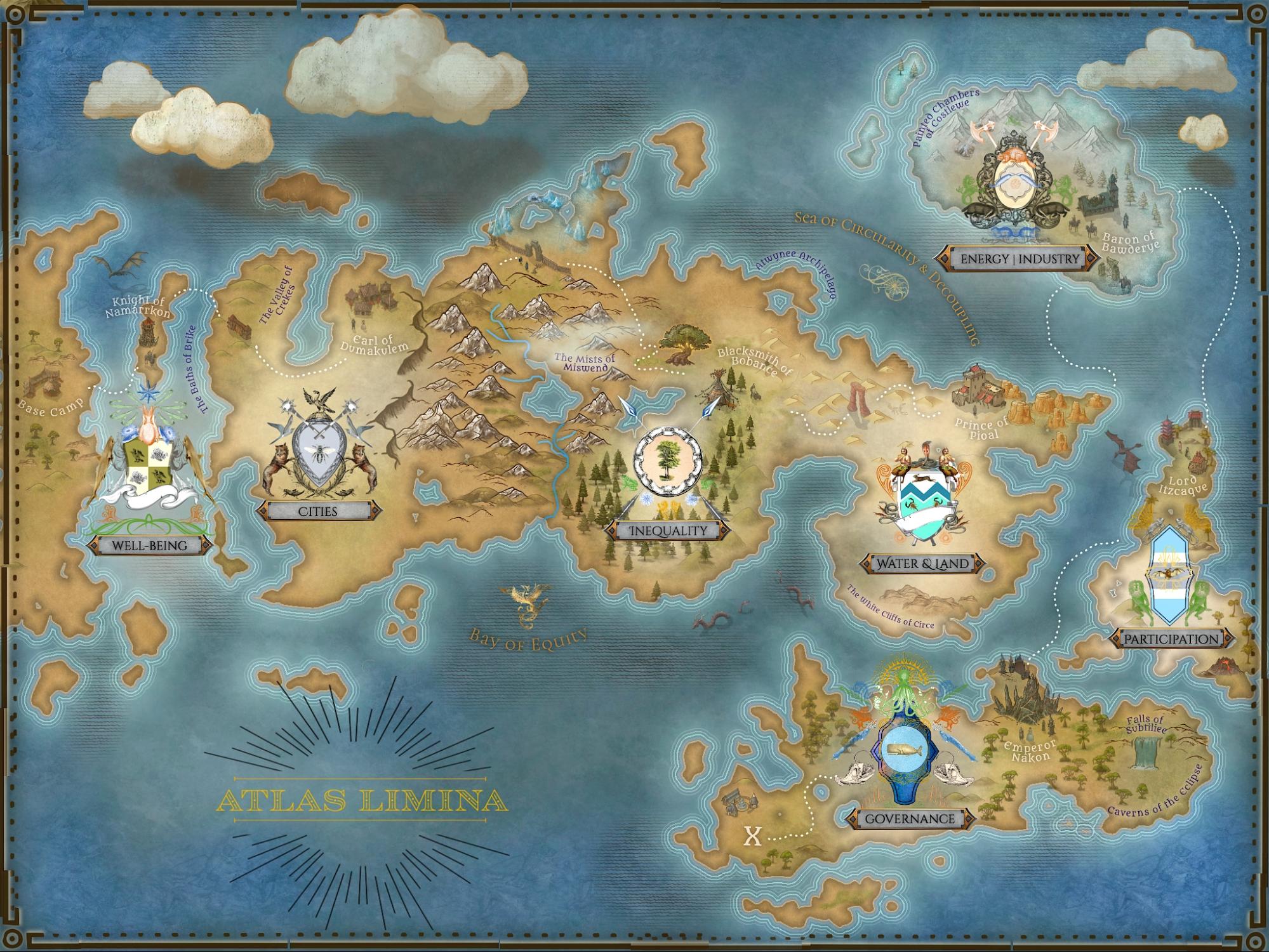

In the class I was designing, I modeled this new world. It became Atlas Limina, The Map of Thresholds. It focused on seven fundamental transformations (modified from Sachs et. al., 2019) that catalyze action in order to achieve all 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (the United Nations 2030 Agenda) while remaining within planetary boundaries (Rockstrom et al., 2009; Steffen et al., 2015). I conceptualized these seven transformations as “Territories” in the map included below.

The 7 Key Synergistic Transformations (“Territories”) (modified from Sachs et. al., 2019):

1. Education, Gender, and Inequality

2. Health, Wellbeing, and Demography

3. Energy Decarbonisation and Sustainable Industry

4. Sustainable Food, Land, Water, and Oceans

5. Sustainable Cities and Communities

6. Participation [modified from Sach’s Digital Revolution for Sustainable Development]

7. Holistic Governance

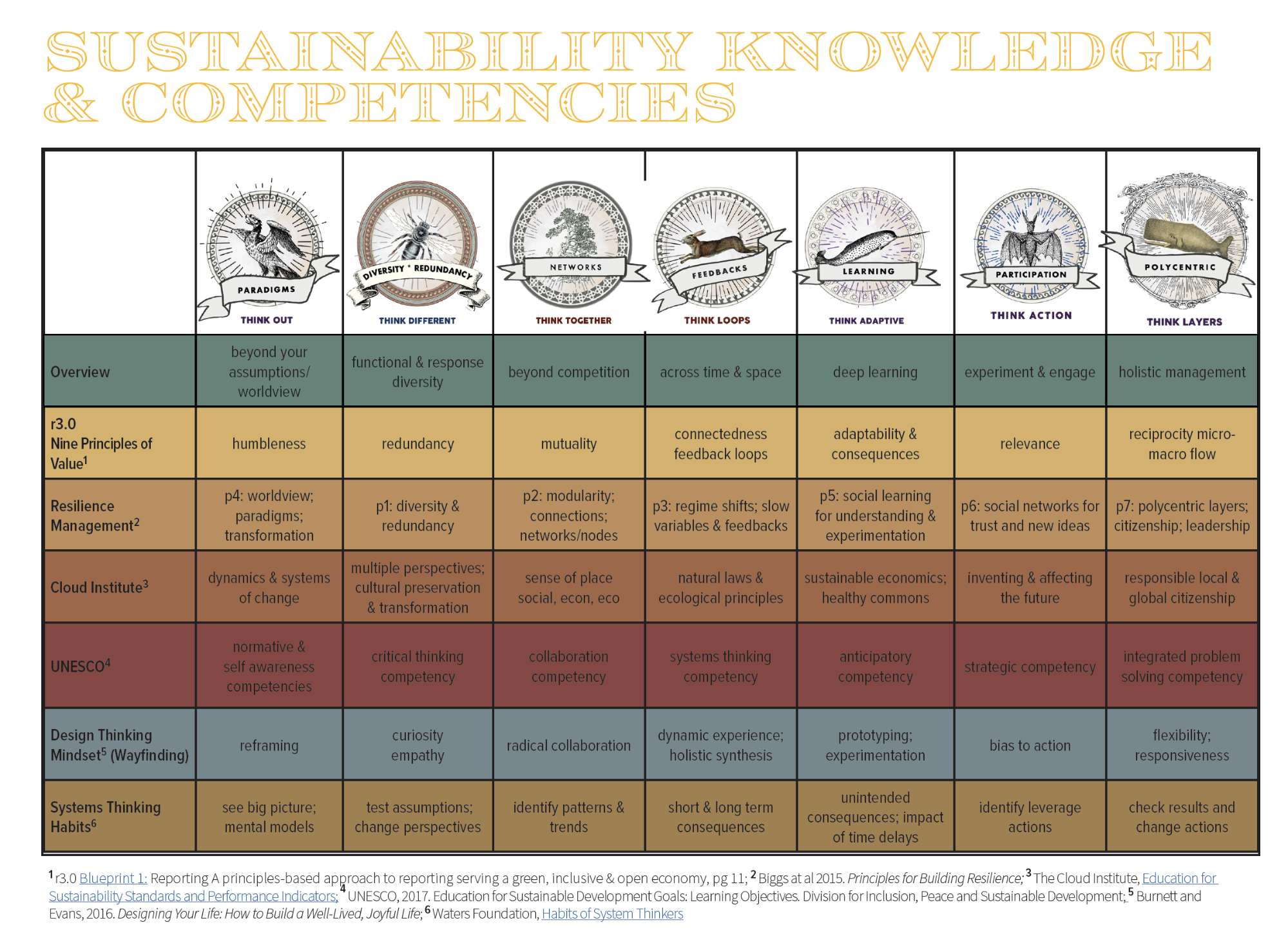

I imagined students in my class investigating each territory, deeply exploring mindsets and systems thinking, and discovering traps and patterns of understanding often encountered in the Begulier’s Basin. I introduced these patterns as the Seven Resilience Mindsets, badges that students could achieve after they completed the challenges set forth in each territory.

The Badges

The 7 Resilience Mindsets (“Badges”) (adapted from Biggs et. al. 2015):

P1- Maintain diversity and redundancy (“Think Different”)

P2 – Manage connectivity (“Think Together”)

P3 – Manage slow variables and feedbacks (“Think Loops”)

P4 – Foster complex adaptive systems thinking (“Think Out”)

P5 – Encourage learning (“Think Adaptive”)

P6 – Broaden participation (“Think Action”)

P7 – Promote polycentric governance systems (“Think Layers”)

The Resilience Mindsets use expanded thinking to encourage students to extend their spatial and temporal realms of moral consideration, to respectfully reveal and challenge their own assumptions, and to listen to other perspectives with compassion and curiosity. The mindset competencies work together to help reshape human perception, accounting, and decision-making in a dynamic and interconnected world.

The course explores essential concepts of transformative sustainability and environmental justice, comparing them to incremental sustainability (which often focuses on producing less and less pollution, toxins, carbon, etc., instead of generating more “good,” like the human, social, and natural capital that is the focus of transformative sustainability). Students investigate systems thinking tools that reveal the nature of complex adaptive systems and the role of feedback loops and tipping points—things that are often concealed from normal human perception. These hidden elements also invite discussion about the role of uncertainty, nonlinear change, and surprise in predictions, scenarios, and projections of future states.

The students’ learning trajectory helps young scholars develop a creative imagination and an intellect that fosters resilience, regeneration, and the ability to see positive opportunities for the future. Together, the students and the teaching team nourish imaginative capacity by identifying and honoring multiple ways of knowing, including traditional ecological knowledge. As students grow to appreciate these diverse epistemologies and experiences, they explore new methods of measurement—like multi-capital assessments and narrative reporting—that help discern and distinguish outputs that are more than numbers.

The interior landscape of the students’ growth is essential to the course as well. Individual development tools help the scholars understand cycles of creativity and renewal within themselves, enhancing their problem-solving capacity. Weekly adventures of deep learning and reflection assist them in building dexterity with meaning-making in their lives and careers. The course strives to help students identify and claim their own agency as positive change agents, and strategically assess opportunities in a variety of sustainability career and job pathways.

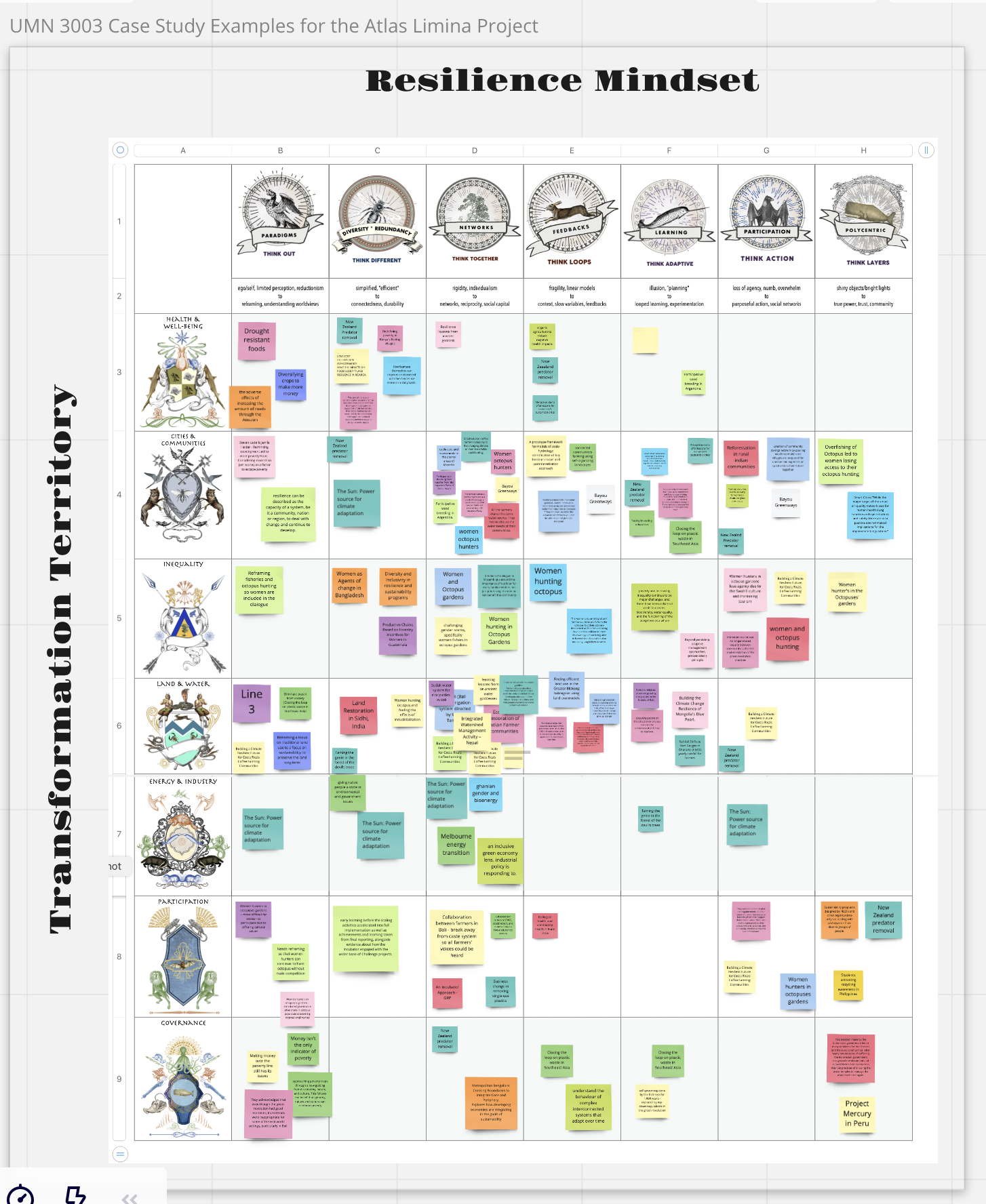

I was curious about how students would receive the Resilience Mindsets and the ideas of Atlas Limina. Was this a useful framework from which to explore new ways of thinking? Was it too esoteric, too weird, too complex?

In the spring of 2021, I did an experiment in my 3003 class, Sustainable People, Sustainable Planet, which included about 85 students. I gave them a wide-ranging list of sources for case studies about transformative sustainability, and the students set out to find real-life expressions of communities and initiatives that embodied life-centered design, long-term thinking, an understanding of systems and feedbacks, an endorsement of experimentation, and comfort with uncertainty. Their responses set the foundation for a database of evidence and inquiry about these ideas.

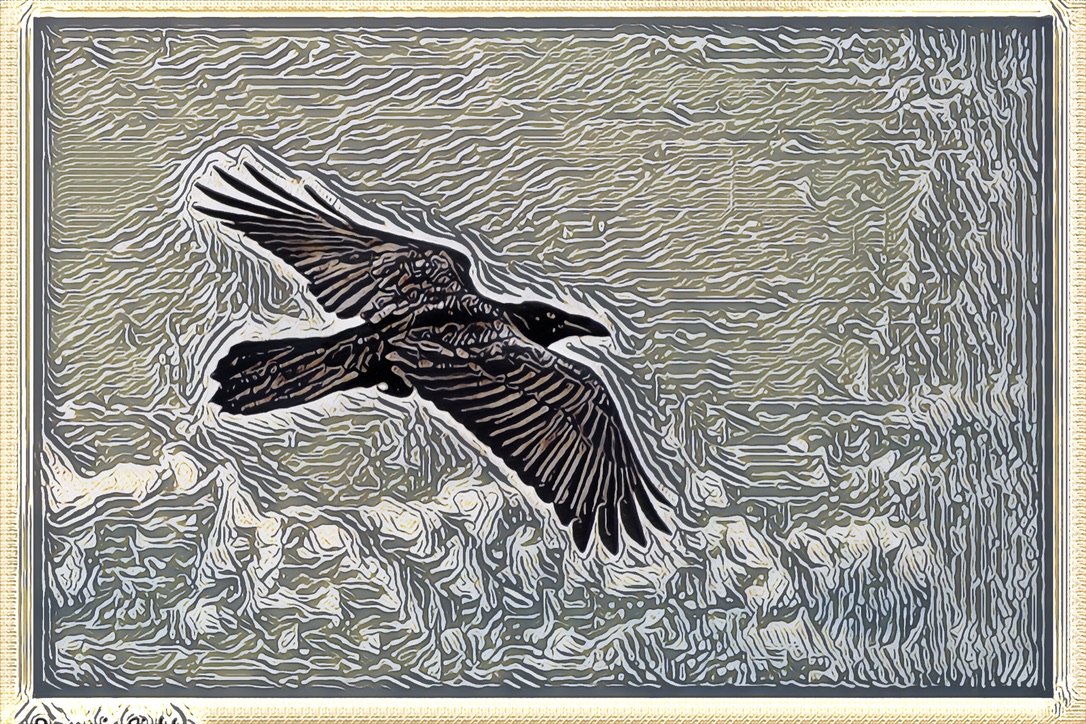

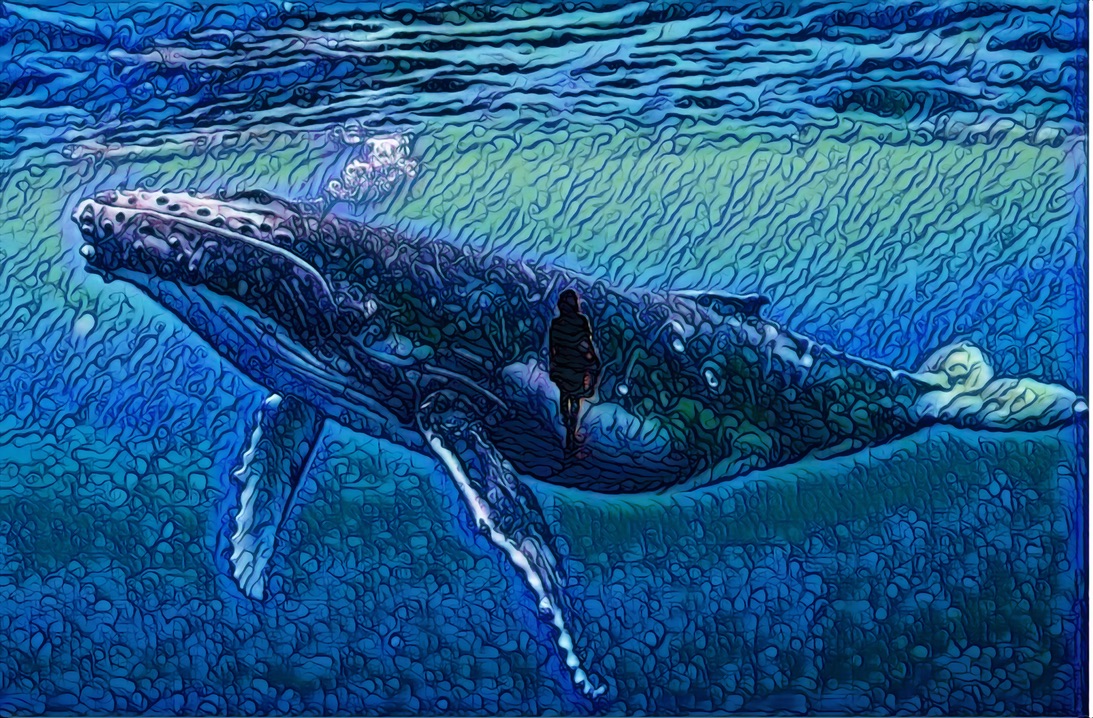

I included a survey about the study’s design in the assignment, and I was thrilled that the students responded in an overwhelmingly positive fashion. Even the elements that I thought were merely playful and fun proved helpful. For example, I developed the idea of Biomimicry Ambassadors who represented physical manifestations of resilience thinking skills and tools. Microryza of tree roots reminded us of the communication and support systems within forests, where symbiotic relationships between disparate species facilitate the flourishing of the community. Whales told us about their ability to distribute nutrients amongst different strata of ocean waters, and the helpfulness of mixing layers (or mingling scales of governance).

I created shields for each transformation territory in Atlas Limina, embellished with historic images of the ambassadors for that region. For example, the Healthy Cities and Communities transformation territory occurs in the grassland biome of the map. The bee in the center represents colonies of social insects that self-organize, coordinate activities, and carry out complex group tasks through numerous individual interactions. The phoenix at the top of the shield is the ally gained—the prairie flowers in post-fire habitats that are stimulated to germinate by chemical substances in smoke. The threshold challenge involves the system archetype “Limits to Success,” where the best of times become the worst of times. This is symbolized by cuckoo birds, some of whom are brood parasites, laying their eggs in the nest of other (unsuspecting) bird species, who subsequently raise the hatchling without questioning the intruder. Wolves serve as the anti-story, warning of the dangers of simplifying systems by removing top predators. Grasshoppers or desert locusts are the sidekicks, warning us of pitfalls. These insects normally live independent from one another, but an overabundance of locusts can stimulate serotonin in the creatures, causing them to gather together in swarms, with devastating impacts on agricultural areas.

Act Four: “Mysteries of the Rupture”

This approach was not well-received by traditional academia. “We don’t need that. Why can’t we just teach systems thinking the way we have always taught it?” asked the Threshold Guardians of education. Well…because it’s incredibly difficult to teach systems thinking well. Students go into overload or fall asleep. Teaching about complexity and feedback loops and nonlinear systems is like teaching a new language, and a new way of seeing the world.

My ghosts grew bigger. I thought it would be easier to hide than keep going. What was I thinking? This was just another example of how I don’t fit in. And then I felt the rage: Where was the mystery in teaching today? The joy? The playfulness? What was this saying about the wonder of the world, awe, and the greatest gift we can give to students, curiosity?

Must we always see nature as predictable and manageable? Must we live in a world solely defined by scientific truth, where the non-human and the non-science lack meaning? Don’t get me wrong, I love science. I wrote undergraduate textbooks about environmental science. But does it have to be either/or?

I saw a suppression of different ways of knowing. I saw it in academia, I saw it in my field of study (conservation biology), and I saw it on the balance sheet of every household and corporation.

Things were falling apart. I was falling apart. Existential crisis. Did I really want to believe that the world was magic, a place of hope and abundance, even if it would cost me everything? I was asking dangerous questions.

I was in the belly of the whale and I could feel the bones of the whale’s rib cage: smooth and bright, enclosing me. In my meditations, I lay on a tabletop. The table lifted up from one end, and my colors ran out. Let it go, I said. Finally. Just let it all go, everything I held dear. The worlds I had constructed dissolved as the wind carried away their grains of sand.

But I wouldn’t let the project die—it came back to life, again and again. Bubbles on the cauldron, rising like a phoenix, or maybe, if I was cynical, a zombie that could not know death.

In one of those incarnations, I met a fellow traveler. A mentor, a wise sailor, who was joyful and playful: She felt the freedom of jumping in with abandon. We shared pictures of female pirates and buried treasure, and we danced together, weaving art and science, thinking and knowing. The Atlas became a freshman seminar titled “Radical Imaginings: Art, Science, and Resilience / Creating Emancipatory Change for Transformative Sustainability.” Maybe it would find a home. But, no, the Threshold Guardians held firm. This was just not how we do things around here.

There were other teachers, too. Their gifts would come in surprising forms—a cartoon, a game, a book on quitting. These guides were making their own maps, and they understood the humility and the curiosity required for such a journey. We dreamed of classes that would embrace a deeper dive into holistic consciousness, Macy’s “holonic shift.” These teachers could at least see a way out. I renamed my map Territories of the Apprenticene.

These wise ones understood our need to move beyond human exceptionalism and our stories of domination, alighting on shores more cooperative, collaborative, free. In dreaming of these classes, we knew that we would teach what we ourselves needed to learn. We were not masters of content by any means, but intrepid adventurers, led by our curiosity and uncertain where it would lead. Adventure was calling, and we knew that in many ways, the map would unfurl beneath our feet as we walked the path, and that the line of demarcation between teacher and student was often an illusion.

Dropping the Rope: Mysteries of the Rupture

The wise one said: You have tried the fear route. Now try something else.

The Beguiler’s Basin was losing its grip on me. Once I could put a wedge, even the smallest wedge, between me and the story, it started to crack. The ruptures opened with a single question, considered from a center that was not located in my mind: “Is it true?” Who benefits from the story of the Beguiler’s Basin? What is sacrificed in order for me to keep that story alive?

In this small rupture, I saw the ways I alienated myself from myself. This was the upper zone of the basin: Separation of self from Self. I could see how my own mind was colonized and trapped in a world of “either/or,” of “better than,” of supremacy. The burden became too heavy, and I was cracking under the pressure. My body shook and tears were always near the surface, even in the middle of class—someplace that had before served as a refuge, something sacrosanct. Now I could feel the true weight of what I was carrying, and ordinary ways of perceiving time, space, causality, and agency were disrupted, morphing into something terrifying, maladaptive, almost zombie-like. It had been eating me whole all along, and I kept carrying the package because it was familiar. Every day the weight grew heavier, more burdensome, until finally my body collapsed, and I dropped the rope. The rope of ambition, of meaning, of my capacity as a change agent, all of it. I just put it down.

Maybe this was the practice of non-resistance, of succumbing to what is. I could see then that my source of power came not from controlling things, but from letting go. Controlling things was foolish, like trying to control the wind, which comes from all directions—just like the movement of people pushing towards justice, the power of the earth’s soil, or the power of water rushing through the veins of plants.

This was something so much bigger than me, and thank God. I was tired of myself and my old stories, the repeating patterns, and the basins. Now that I could discern the Stories of Separation within myself, I could recognize that separation from self was the final layer at the top, the greatest challenge. In an instant, I could see that self, nature, and community were all the same thing. This flash of insight lasted only for a blessed minute. Then the Beguilers’s Basin collapsed in on itself, like one of those collapsible strainers. The ground became flat, and I could walk out. The basin was gone, and no longer had the power it once did.

Act Five: Lighthouse flickering, phase transition

As the Basin collapsed behind me, I could see the vast expanse of what was before me. It was a suspended, otherworldly state: A place with no gravitational pull towards either basin.

Scientists studying phase transitions in marine environments say the ecosystem flickers back and forth when the system state is between basins. That no-man’s land, the uncertain territory, the saddle between mindsets or stable states: it was a dangerous place, indeed.

I could get lost for years in Swende Hallows, where cynical ghosts—shells of people who once dreamed of a better world—circled the swamp within the husks of their dreams. In the other direction, I saw the Valley of the Pompous Ass, a place I had been before, a place of great pain and terrifying ego. Here was the self that was hidden all along: the ego of being right, of not wanting to offend, of hiding. But there was no place to hide here; the sun bleached my bones and scorched my skin. In three days of diversity training, I found a moment of truly seeing another in their fullness. A hug given by a chief in the Medicine Garden offered me passage, or at least a ticket to see my blinders, if only for an instant. The petals of stained glass that surrounded my thinking pulled away and dropped from my body, crashing below. I cried for hours, broken, in total surprise that the beauty of that glass, its shell and protection, was just an illusion. Another trickster.

With nothing left to hold onto, I was facing the terror I had been running from my whole life. I can’t think myself out of this transition. “The body keeps score,” they tell me. So here I am at the threshold between basins, a place far more eerie and powerful and haunting than I could have ever imagined.

The Beguiler’s Basin had a sense of urgency about it. I had wanted to get out of there, and fast. I was willing to undergo pain and torment and suffering in that journey because I could clearly see the line of division—there is a space where the basin is, and a space where it is not.

I thought it would be smooth sailing once I left the Beguiler’s Basin behind. But the land between basins is full of mist, fog, and illusion. I find this land far more dangerous than the sharp agony of the Beguiler’s Basin because I am filled with a suspended sense of…nothing. No dreams. No not-dreams. Just wandering. It’s easy to get lost.

Part of me knows that there is life beyond this uncertain territory. Sometimes I can see past the threshold, into a world of new eyes that exists within the basin of Lifelode Kype. The Kype is a world of integration, of little self within big Self, as the deep ecologists remind us. It is a landscape of interconnection, someplace with room for each one of us and our own unique gifts.

I am so close to this place of belonging, trust, and abundance. I can see it through the haze. But I wonder if I alone can pull myself through the gate. Is this the secret of the threshold passage? That the work is collaborative, co-creative, and founded on trust? This is real trust, not some pleasantry kind of trust. Trust in the goodness of others, trust in the goodness of my own self.

The wise ones said, “It is selfish of you to hold on to your old terrors, your patterns, your stories of smallness.” The wise ones said “We need to see you; we need your strength, your courage and compassion, so we can see it in ourselves.”

Isn’t that where many of us are now, in the uncharted territory between basins? We know that the old story of carbon and fossils and human dominion left us empty. But we are wandering, unsure of our commitment to a life-affirming basin that we cannot fully see. It feels risky. It seems much safer to be here, in a land of shells and husks and egos and puffery. If we are to take the leap, we will need others to pull us over the threshold. On the other side, in the basin of Lifelode Kype, the world is rich and nuanced and full of color. In that landscape, grandmother trees send messages of warning through mycorrhiza on their roots, and notes of encouragement and healing in the form of extra nutrients to troubled trees. These roots and branches are reminders of the ribbons of energy within and between species. These connections tell us that we are not alone on this earth, even though we may feel so in our darkest nights.

The interconnectedness of life flows between us all: cloud and flower, sapling and soil, warbler and whale. It is our most noble and fundamental work to pay attention to this wild magic. To notice and cherish our bonds of connection, to see and name the systems in which we are embedded: food, water, mineral, energy, soil. This work helps us remember the power of regeneration: the fundamental truth that the world is alive, and our relationship with the rest of life is one of participation, communion, and co-creation.

It is all of us, smashed beautifully together in Thich Nhat Hanh’s Interbeing. This interbeing is revealed by looking at a flower, and realizing that the flower mostly consists of non-flower elements. The flower contains clouds and rain and compost and the gardener’s care. Just like you and I.

Notes:

- Portions of the last three paragraphs appeared in a talk I gave on Earth Day, 2019.

- A beautiful article from the STEPS Centre, “The World has Become Weird: Crisis, Natures, and Radical Re-Enchantment” by Amber Huff and Nathan Oxley, inspired the titles of some of the “acts” in this story: “Epistemic Entryways” and “Mysteries of the Rupture.”