3 Spiritual Frugality: An Islander’s Tale

Kristin Osiecki

“We must let go of the life we have planned, so as to accept the one that is waiting for us.”

Joseph Campbell

My journey writing my eBook sustainability chapter involved a heartfelt reflection on my chosen path into environmental health, justice, and equity. This examination led to something much greater than the different, individual parts ingrained in my memory. Having grown up in an industrialized, working class suburb of Chicago, I first created an outline focused on my personal experiences observing the world around me. When I was young I dreamed of going to college, maybe in a scientific field such as chemistry or biology. I did not know much about humanities, social sciences, or art because at the time I did not believe that such knowledge would help me get into a competitive school. I was motivated to prove myself and ultimately find a career path that would elevate my socio-economic status.

I applied to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in biochemistry. Although a decorated student in a low-performing high school, I discovered that my study skills were weak, and that after traveling an easy road I was now competing with students who had greater intelligence, support, and opportunities. As a first-generation student, I struggled in the isolated chemistry and physics laboratories, finding no connection to my unknown passions and pushing through reports, theorems, and calculations. Nothing made sense, and I felt hopeless.

At the beginning of my sophomore year, I went to the student employment office to look at the hundreds of university jobs posted on index cards pinned to bulletin board walls. Searching with my head tilted back and my eyes gazing above, I found a description of a laboratory inspector for the division of environmental health in the health physics department. I pulled the card and traipsed across campus to an older building with worn black letters stuck to a yellowed-glass window pane, and with a calming aroma of dust and tradition. I interviewed with an eclectic hipster named John and a newly hired inspector, Darren. I learned that health physics involved research using radiation and laser beams, and that the student position focused on low-risk labs in all scientific realms using tritium and Carbon-14.

I got the job. Each month I surveyed over 200 laboratories in psychology (rats with nodes sticking out of their brains), veterinary science (cows with clear panels to show digestion), and entomology (cockroaches and the hum of insects), just to name a few. This experience changed my life. By my spring semester, I had changed my major to community health education, made awesome friends at my workplace, and begun a rewarding academic career with dedicated professors who saw my potential. Drs. Creswell, Goldstein, Van Winkle, and O’Rourke helped me find my passion and, more importantly, encouraged me to go to graduate school. I had found my calling.

My journey has not been straightforward. There have been twists and turns, dreams lost and then found, but always the love of family. Exactly 25 years after earning my bachelor’s degree, I started my journey toward a PhD at the University of Illinois at Chicago, School of Public Health, Division of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences. With a terror of taking public transportation and of finding the right bus routes, L-trains, and subways, I often found myself lost. Over time, however, I realized that in so many ways I was being found.

After graduation, I packed up my car and drove 19 hours to Houston, Texas, my first time living outside the Midwest. I had been hired as a post-doctoral researcher at Rice University, working with sociologists and collaborators from the University of Texas and the University of Houston. They showed me a bigger world and different ways of thinking about things.

Originally, I planned to focus my book chapter on the academic experiences that have shaped my love for environmental health, sustainability, and communities as I continue my career at the University of Minnesota Rochester. But my outline changed as I explored the joy I find in research and the search for knowledge. There is a saying that it takes three generations for the past to become lost as traditions change, people move on, and the stresses of the common day somehow become greater than those of previous times. This chapter begins with the journey of my childhood and my second-generation experiences with my grandparents and my great aunt and uncle. I continue by exploring the rich history of the past during the times of my great grandparents, early colonization, and the original owners of the land on which I grew up, the Illini Indians.

As I worked on this chapter I realized that looking back to our lives and examining sustainability is how we move forward. We need to take responsibility for historic wrongs, find a new appreciation for the land, understand how we got here, and then revere those who came before us and who embraced sustainability before sustainability became a priority in the new world order.

Section I. Grandma and Grandpa, Landfills, Brickyards, and Illini Lands

It is a crisp fall day with leaves in bright yellows, oranges, and reds. The wind swirls the fallen leaves in the middle of the grimy street. I am walking to my grandparents’ house for Sunday breakfast. Western Avenue, usually busy with cars going in and out of Chicago, is quiet this time of day. It makes it easier to cross the street without playing a game of chicken. It is a peaceful walk in the “better part of town,” lined with old Victoria homes that are masked behind an early morning haze. I have several favorites, like the Tudor with draping rooflines, and an Italianate with turrets, stained glass windows, and cookie cutter accents along with a majestic garden and wrought iron fence. The sun is warming up the cool morning air filled with dampness and the hint of a foul smell. I turn the corner and begin skipping the rest of the way.

It is an unassuming 1200-square-foot brick house with two bedrooms and one and a half baths. A one-car garage sits at the back of the property, with two strips of concrete and a center grass median leading to it. The city lot has a victory garden and a compost pile that rests along the alleyway. A bountiful harvest was enjoyed in the summer and preserved for the upcoming winter. The side door opens to worn yellow linoleum tiles with four steps going up to the main floor. The living room has the original carpet and furniture from the forties. Never rearranged or changed, never used except for holidays, always immaculate. There is a small full bath, a bedroom, a kitchenette, and a closed-in porch with a television playing Chicago sports, old western movies, or Lawrence Welk. Upstairs is an attic bedroom with a half bath that, years ago, was often filled by four children and my grandma’s mother hunkered in the tiny space with low, angled ceilings.

When I arrive at the house I head down the four stairs into the concrete basement with dark red tile. Together with the familiar dampness, the smell of sizzling sausage fills my senses. The kitchen holds a varnished cupboard, a large stainless-steel sink, an-old fashioned refrigerator, and a stove built to last. A coffee pot percolates in the center of the kitchen table; powered by an extension cord hanging from the ceiling, the large silver bucket with a clear knob churns brown liquid. Grandpa built the large, solid table, which holds at least 10 old-fashioned metal folding chairs. Because of the uneven basement floor, he constantly tinkered with the legs by shaving off slivers of wood to stop the rocking. If you were not careful, your knees would hit the tabletop, causing a jolt and hopefully not toppling any hot beverage.

The basement is unfinished, with exposed beams and walls covered in paint. The kitchen/dining area, a desk with a mirror, a washer and dryer, and a utility tub with a big piece of Lava soap complete the space. A clothesline is draped from one end to another for drying clothes in colder weather. (Energy conservation is a priority, and the gas dryer is used only for towels). A microwave is eventually added—on a simple stand hooked up to a light switch to save the electricity used by the digital clock. The thermostat is kept at 66º in the winter, and there is no air conditioning in the summer. Better decide what you want prior to going into the fridge, and never leave the water running.

Extended family start arriving from church and the relaxing time spent conversing with my grandparents transforms into a whirlwind of activity, laughter, and conversation. My request for two over-easy eggs is first on the line. Grandma hollers that they’re ready, and I run up to the stove with my plastic plate for two perfect eggs and a piece of kielbasa. I head to the toaster to pick up my homemade bread, almost burned (my grandma would always say burnt anything is the best). On the cupboard are a stack of Yoplait yogurt cups for the kids (back in the day when they came with a plastic lid) for milk or orange juice. The adults fill jelly jars or old coffee cups with the strong black liquid.

My grandparents embrace the concept of reduce, reuse, and recycle. It is not called sustainability, but there is an inherent belief in frugality and minimizing waste. This frugality is income-driven in part, after both the 1918 flu pandemic and the Great Depression, but it is more than that. It respect and humility toward what we have and, more importantly, what we really need. More is not better. My grandfather wears the same brown polyester suit to every special occasion. My grandma gets her hair set each week (by the lady with a salon in her basement down the street), uses Ivory soap for everything, and splurges on the traditional Oil of Olay face lotion (which makes her look timeless).

As family members trickle to the table, I take a last look at the goodies before I am asked to give up my spot: cinnamon coffee cake, tomato jam with bread, rhubarb pie, and chocolate sheet cake, to name a few. I fill my plate and move to a chair on the perimeter near the china cabinet. My grandma says that a traveling salesman knocked on the door selling bone china sets and she decided to buy one. An unexpected purchase from a penny pitching family. The china is never used, which preserves the gold rim and the painted dogwood flowers. They’re in perfect condition except for the two handles broken off the sugar bowl with no explanation why. “DISHES, DISHES, DISHES,” yells grandma. That is my cue to start drying all the dishes used in this wonderful brunch.

The basement kitchen is the heart of their home. Thanksgiving and Christmas Eve dinners require numerous folding tables and chairs to accommodate at least 30 people. Twice a week we have family dinners of gwumpki and mashed potatoes, vegetable beef soup, stews, and pot roasts that warm my heart and soul. Every Saturday, my grandma bakes bread and stops by our house with steaming rolls that only need a pat of butter. Sometimes I go to their house after school and my grandpa makes me a liver sausage sandwich. He also fixes things like my bike, a clock, and later my car, often with a few pieces left over. He teaches me how to ride his small motorbike (made from a lawn mower engine), fish in a pond, and change a campfire’s colors with copper wire.

It is such a beautiful day that I decided to walk home. I choose a slightly different route that includes more of the larger Victorian homes built by wealthier residents in the late 1800s. The wind changes direction and the local garbage dump bursts my perfect afternoon with a strong rancid odor of rotting food, chemicals, and indescribable carnage. The serenity I had felt early in the day disappears as the western wind provides a stark reminder of the Sacramento Municipal Landfill, only six blocks away.

Blue Island, Illinois, is the first suburb of Chicago. It was established in 1836, one year after Chicago. The folklore surrounding Blue Island’s name revolves around two different stories. First, residents of Chicago often traveled to the “Islands” to shop at the Western Avenue open-air market and other businesses. One woman described the acres of wild blue irises that surrounded the marshy areas along the ridge. The second story is based upon hunters traveling to the ridge and observing an indigenous tribe whose members painted their faces blue and were called “the blues of the ridge,” or blue Indians.

My ancestors immigrated from Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Eastern Europe to Blue Island in the 1800s. They were either farmers or worked for the railroad. By the time I visited my grandparents in the 1970s, their home was less than a mile from a municipal waste landfill, where tons of garbage were dumped into a massive hole and acrid smells, noxious insects, and random pieces of paper followed the airstream. A few blocks from my childhood home on Vincennes Road was a hazardous waste landfill that contained volatile organic compounds, PCBs, and heavy metals.

As recently as 2011, this site received $600,000 from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Brownfield Fund for remediation. But even after clean-up, it will only be suitable for commercial use.

In the late 1970s the Vincennes Dump is covered with dirt, and it becomes a dusty trail on which we ride dirt bikes. Family members gun the engines, barreling up the steep mounds to jump onto the top of the pile. As for me, going just fast enough to keep the bike standing is enough of a risk for me. Little do I know of the health risks that lie beneath.

From 1993 to 1996, the U.S. Geological Survey conducted a study called “Characterization of Fill Deposits in the Calumet Region of Northwestern Indiana and Northeastern Illinois.” The political boundaries associated with this study show the region and, more specifically, the town of Blue Island on the western side of the map. The Calumet Sag Channel divides the town in half, connecting with the Little Calumet River that leads into Lake Michigan.

The map is also coded to show the different types of land use. Approximately half of Blue Island contains petrochemical industry, other types of industry, and waste treatment and disposal. The other half is either natural, residential, or open water.

The natural areas and open water might seem like great places to explore, but they are covered with litter and overgrown from neglect. Instead, I walk to Hart Park to watch little league games, or ride my bike to the Kiddie Koral, a small playground underneath the water tower. Memorial Park, with the public pool, is a great place to cool off during the summer. However, it is several miles away and the bike ride home in the stifling heat makes returning to my bedroom with opened windows and no fan that much more difficult.

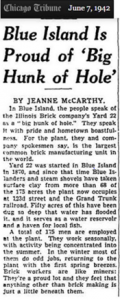

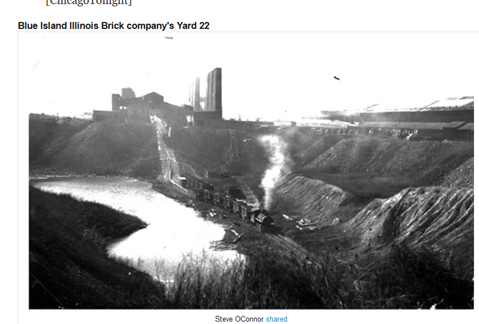

The brickyards in Blue Island were born of necessity—because of the optimal clay mixture in the area, and because of the overwhelming need to rebuild housing destroyed in the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. Homes, shanties, and slums built with combustible materials had fueled the devastation, and led the city council to require that homes be built of brick so they could withstand the heat of flames. Brickyard Number 22 was located close to my grandparents’ home. Vincennes Road hazardous dump is also the result of repurposing a brickyard.

In my childhood, the only thing I know about the brickyards is that they’re the basis of the name of a popular bar that sits near the high school.

The Vincennes Trail was named for the first established town in Indiana, which in the 1700s included a British fort. A Revolutionary War battle between the French and British resulted in the unconditional surrender of the British. In the mid-1800s, the Vincennes Trail connected the old Fort Vincennes in Indiana to Fort Dearborn at Chicago. It was later turned into Vincennes Road, which remains a main Blue Island throughway. Blue Island has a proud history, one meticulously captured in books descripting the proud settlers who built a thriving community only 12 miles from the heart of Chicago.

Before the settlers colonized this area, the lands belonged to the Illini Tribe. The tribe first encountered Father Marquette during his explorations in 1674–1675; he also traveled with Louis Joliet, a French-Canadian explorer. According to historical interpretations of his journals, Marquette and other missionaries established a mission on the Calumet River, near Palos, to convert tribe members to Christianity.

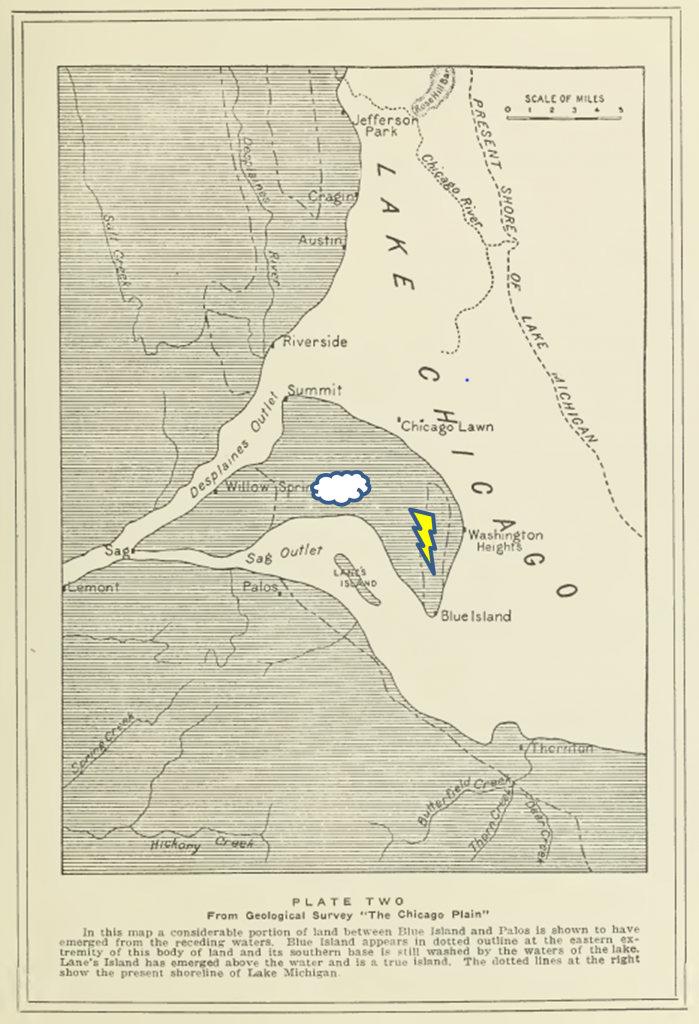

The map above illustrates the original geological formations. The cloud represents Wildwood; a few miles east is Blue Island (the lightning bolt). The land was surrounded by water, with shores touching Lake Chicago, the Desplaines River, and the Calumet River outlets. At that time, Blue Island and Wildwood were a true island, with fertile hunting ground for the Illini Indians. Wildwood was the former place of their council, and burying grounds of the Illini Tribe were located in Wildwood before the tribe migrated toward the Blue Island area.

Their villages thrived with plentiful fishing and bountiful crops of Indian corn, beans, melons, and squashes. The Illini lived in roofed cabins with floors made of rush mats. Cooking utensils were made of stone, wood, and bone, and ladles were made from animal skulls. Animal skins were turned into garments for the women while men relied on minimal garb.

The Ciinkwia story of Grandfather Thunder and the Thunderbeing Story resonates with me: “We always give thanks for his many gifts to all land and life upon Mother Earth.” The respect for land, our elders, and the role of a grandfather is handed down by generations, and I wanted to share this story to conclude this section. It is important to remember history, traditions, and those who came before us, and the story gives me a new appreciation of the sacred grounds that I unknowingly explored as a child. I wish I knew that the memories the sacred ground holds are not just my own.

Thunderbeings – Ciinkwia

Grandfather Thunder[1]

Muxumsa Pethakowe, our Grandfather the Thunder, was father of the first people, and the Moon was the first mother. But Maxa`xâk, the evil horned serpent, destroyed the Water Keeper Spirit and loosed the waters upon the Earth and the first people were no more. Since then, the Thunderers, Pethakowe`jàk, have always been on the lookout for the Maxa`xâk and other such evil water monsters, and when one appears, the Thunderers shoot their crooked, fiery lightening arrows at them, hoping to avenge the details of the first people and to make sure that none of the evil shall ever disturb the harmony upon the Earth or cause harm to our Lenap`wàk.

Long ago, there was a time when Grandfather Thunder was forgotten among our people, unlike Grandmother Moon who has always been remembered and honored by us. He became bitter and despondent over our neglect and forgetfulness of him, and in his anger he came from his home in the west, calling out in a voice that shook the heavens and the Earth. Hidden in clouds, he crossed right over the homes and villages of our people. In his fury he shot lightening arrows at the Earth, killing people, burning houses, and shattering trees, and the clouds cried their tears of sorrow upon the Earth. Luckily, he never stayed in one place too long, and usually was seen traveling towards the east.

At first he would come alone, but after a while his many children came with him, and they frequently brought fear into the hears of the Lenapé people. Some would come from a cave under the falls known today as Niagara and others came from the mountains where they often made their homes.

At the sight of dark clouds and lightning, and at the sound of the thunder, being the roar of the wings of the Thunderers and the shaking of their rattles filled with bones, which shook the sky, our people became most fearful.

Nanapush finally sawa that we, his grandchildren, were in distress and so he came to help us saying, “You have hurt and insulted your Grandfather Thunder through a lack of respect and thought for him. Grandfathers need to be remembered and honored too, for they also, like grandmothers, have shared in the gift of life and in helping their grandchildren in the future. So, when you first hear Grandfather in the spring, telling you that winter has ended and that life is again coming to the Earth, burn tobacco and greet your grandfather with prayers.

“Whenever you hear his voice, do this and you will gain his protection and lightning will not strike you. Grandfather has charge of the rains that water the Earth and make your crops grow. With the proper respect, he will be thankful, bringing blessings to you, and protect you from the horned snakes and water monsters, and he will come to bring you warnings!!”

From that time to this Grandfather Thunder and our Lenapé people have always been close. We listened to our wise Grandfather Nanapush, and we have always shown respect to Old Thunder and love him dearly, and we always give thanks for his many gifts to all land and life upon Mother Earth.

Section II. Great Aunt and Uncle, Railyards, Calumet Sag Canal, and Colonization

My great aunt and uncle (my grandpa’s brother and his wife) live across town near the Calumet Sag Canal. I visit them if I can get a ride because it is too dangerous to ride my bike. I see them often at family gatherings, the fish fry at our local church, or hitching a ride to their house with my grandparents. Theirs is an unassuming home with creaky old floors and a worn-out warmth. The brothers sit in reclining chairs watching the ballgame while us ladies sit at a dining room table drinking tea or coffee. Great Uncle and Grandpa were welders, and both have the same tentative walk from a fused lower back due to crouching for long periods in small places. The faint smell of acetylene and permanently stained hands are forever ingrained in their being. Great Uncle tells me that he is now working two jobs: White Castle Hamburgers and Dunkin’ Donuts. He works an hour a day with an hour lunch break. He is my hero and it took me many years before I figured out the joke.

Their home is within blocks of two major train yards. There is a permanent undercurrent of chugging noises and whistles, with soot spewing relentlessly into the wind day and night as tanker, box, and flat cars are slowly pushed onto sidetracks to unload and reload. With only one overpass circumventing the grid of tracks, it is not uncommon for gridlock to clog the busy streets.

It is a residential area bordered by a canal, a river, and a forest preserve. I am told that the area can attract undesirables and I cannot roam the neighborhood even though family members (another brother of my grandfather and his wife) live less than a block away. My great aunt is a calming force for me as she affectionately holds my hand while we catch up with family news. The mid-summer afternoon casts dim shadows in the room, creating a halo amidst the religious artifacts sitting upon old lace linens. Our family attends the nearby Catholic church, originally built in the late 1800s and replaced by a 1970s modern atrocity with dimmed lights and a cold, vengeful aura. I am thankful for my close relationship with my great uncle and aunt, who provide me spiritual guidance, unconditional love, and, most importantly, joy.

In 1852, the Rock Island and Chicago rail line from Blue Island to Joliet became a major hub of rail and trade. In the 1970s, the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad operated 7,183 miles of road on 10,669 miles of track with annual totals of 20,557 million ton-miles of revenue freight and 118 million passenger-miles. Over the years, in the tumultuous business of making a profit and navigating union strikes, the railroad changed ownership; it is currently operated by CSX.

Flashing lights indicate that the gates will soon go down, and we have no idea how long we will sit at the crossing. With no air conditioning in the car, and the windows rolled down, my grandparents put the car into parked gear, and the only thing to do is count the rail cars. Graffiti of slang names, dates, declarations of love, and spray paint artwork cover the cars. My grandparents sit quietly listening to the a.m. radio, not phased by the delay. After sitting for 30 minutes we spot a caboose, signaling the end of this torture. Only then do we see another train on the outside tracks from the railyard trying to move from a crawl to the same slow pace. It looks like we are facing another 30 minutes since we cannot turn around.

The Little Calumet River and the Cal-Sag Canal (Saganashkee Canal/Slough) are part of an industrialized waterway system which is heavily contaminated and floods easily. The canal was built between 1911 and 1922, ultimately becoming a commercial shipping route. Between the 1930s and 1950s, oil, chemicals, and grain passed through its narrow, 60-foot width. Originally designed to move 1,000,000 tons per year, the canal’s capacity was quickly increased to 4,500,000 tons.

The Cal Sag Canal is a stagnant murky brown waterway. The water is choked with chemicals, algae blooms, and fish gasping for breath. Sometimes the locals fish along the weed-covered shore lines as barges slowly push goods and wares to their next destination. The barges are visible as we travel south on Western Avenue toward the Gregory Street Bridge. I gaze out the car window in awe of the incredible sight.

In 1796, the Great Chief Pontiac and his allies from other tribes formed a confederacy to stop colonization of the Wildwood and Blue Island area. The continual land grab and increasing numbers of settlers caused an urgency to fight for survival. The Illini Indians declined their offer, adhering to their own peaceful beliefs. Pontiac lost the battle with the British, due in part to French breaking their promise to join in their efforts. Pontiac retreated to Joliet, Illinois.

An expelled Illini member was bribed by the English with money and a keg of whiskey to carry out Pontiac’s assassination. Motivated by vengeance, those loyal to Pontiac fought with the Illini Villages, causing them to retreat from the Wildwood/Blue Island region to Joliet and finally to Starved Rock. This natural formation was named for the starvation of Peoria Indians who were pushed to the top during a battle with the Potawatomi Tribe. At Starved Rock, the Illini Tribe made one last effort to stand their ground, resulting in the annihilation of all but six members of the tribe.

The story of the Little Creatures of Caprice reminds of the dichotomy between light and dark, good and evil, and the haves and have nots. I think about environmental justice and equity. Why are toxic release inventory facilities and hazardous landfills located in low income and/or minority communities? Who benefits from the products without experiencing the pollution burden and economic consequences?

We can all look up at the sun and feel the warmth on our skin. However, some of us see a haze of particulate matter and ozone as the surrounding toxic plumes make their way into the atmosphere.

The Little Creatures of Caprice Ensnare the Sun [2]

The Little Creatures of Caprice were once travelling over the country when they came upon a hole that gleamed with a sheen of light inside. “Wonder whose hole this might be?” they said. “Come, let us set a trap for the creature!” they said. There upon one of the Little Creatures of Caprice untied the cord from his bow, and making a noose he set it hanging over the place of the hole.

All of a sudden something alive was approaching on the way out. It was so big on its way out as to light up the path and so bright that the Little Creatures of Caprice were blinded in the eyes. Then one of them fetched the bowstring back with a jerk, and he had something alive tangled in the snare. At last upon the ground he flung it.

Whereupon they were addressed by the being: “If you choke me to death forever will there be night!”

Why, lo and behold, it was the Sun! When they found out that he was the Sun, they set him free from the snare. They let him continue forth on the way he had set out.

Section III. Me, Community and History

My urban block landscape is a concrete playground with a smattering of fenced city lots. Paved sidewalks and alleys strewn with discarded matchbook covers and beer cans create a hunting ground for collecting treasures. Across the street, the residential yards butt up against businesses lining Western Avenue, including a used car lot, an old-time car wash, and a cigarette vending machine distribution warehouse, all of which ultimately became great places to play hide and seek.

The street is lined with small older homes and residents who were probably original buyers on the block. Within a decade, white flight and urban blight usher in immigrant, female-headed households, and lower-income families. A six-block radius from where I live contains everything from Section 8 housing complexes (including those built near the old hazardous dump) to small auto repair shops, industrial sites, a major expressway, and sets of train tracks. Beyond this radius to the north is one of the oldest and most expensive Chicago Community Areas, Beverly (aka Beverly Hills).

At a young age, I notice that neighborhoods are different. Riding my bike in the Beverly neighborhood, with its old mansions, beautiful parks, and mature trees, is a magical experience. I daydream about who lives behind the fourth-floor attic window or about the English garden parties in the backyards. A whole other world is only a ten-minute bike ride away. A fifteen-minute car ride on the Dan Ryan Expressway takes us in a different direction, past the Robert Taylor High Rises. I worry about the family in the burned-out unit marked by a broken-out window with a trail of shadowy black soot. I worry about them a lot.

Neighborhood disorder, a concept introduced by University of Chicago sociologists, encompasses both social disorder, such as crime, public drug use, and conflicts, and physical disorder, such as abandoned buildings, noise, graffiti, and disrepair [23]. Physical disorder can also include exposures to toxins, carcinogens, and pathogens or physical stressors such as noise or squalor [23]. Neighborhood disadvantage is defined by the lack of employment opportunities, good schools, green space, and services [23].

When I tell outsiders where I am from, they make fun of me, saying that I live in a bad neighborhood. But there are degrees of bad. For example, the school district childhood program is housed in a predominantly low-income, minority neighborhood. They use a Blue Island mailing address so parents are not scared to send their children. English-as-a-second-language students travel from a nearby Chicago neighborhood and enroll in Blue Island schools with a fake address to escape the violence. Blue Island has its share of crime, drugs, graffiti, noise, and underperforming schools, but I never think it is bad nor are the people who live here. At some point it is a source of pride, especially when they think I am a badass because of my surroundings.

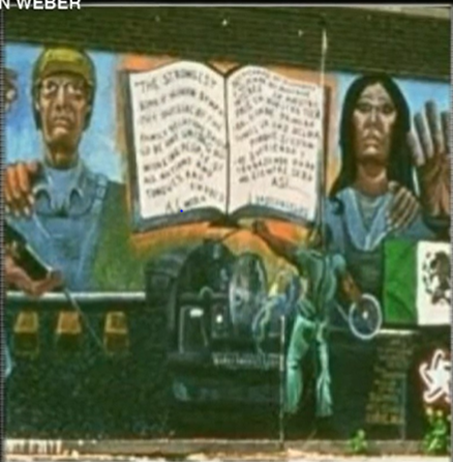

The Mexican-American Worker Mural project (aka The Forbidden Mural) on the El Tapatio Restaurant wall sparks racial tensions as the city council takes legal action to stop it. The mural is ultimately vandalized and over time it’s painted over. In 2016, a new mural is painted on the same spot to depict the working struggles of Mexican Americans.

We drive over the Cal Sag Canal and pass the mural on “Olde Western Avenue” in an area of town named Little Mexico. Nearby is the industrial park, with a mesmerizing glow of lights and pillowing smoke escaping from the massive refinery. I worry about the massive gas tanks and how workers and residents will evacuate if an explosion sends fireballs into the sky.

The Blue Island Refinery, built in the 1920s, inhabits 156 acres of land. Changing names over the years, it provided 300 jobs, all of which were lost by 2001. Petroleum releases from two storage facilities require extensive remediation. Residents are concerned about the spread of contamination in the water and soil. The refinery is near the high school football field, and the smokestacks emitting grey soot create a fine white film on the cars in the parking lot. The expansive industrial area is home to numerous manufacturing facilities, evidenced by a lingering burning smell in the air.

Growing up in a diverse community brought together by the working class struggle, my life is filled with friends and family. Next-door neighbors are first-generation Mexican immigrant brothers who eventually bring their parents and sisters to live on our block. I am excited to be around so many kids, especially my best friend. I watch Mexican Novelas (and learn to understand Spanish), and eat heated tortillas slathered with homemade refried beans or liquid butter and sugar. We walk to school together and attend classes filled with a minority majority of whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. American Bandstand and Soul Train are my favorite shows, from which we learn dance moves and get our fashion inspiration. We walk uptown to the Lyric Movie Theater, the no-name toy store, and the only clothing store around. We enjoy an array of ethnic restaurants, and up-and-coming fast food joints such as White Castle and McDonald (originally a drive-up with no seating area or drive-thru).

Located on the southwest border of Blue Island and formed during the Great Migration, Robbins is the oldest majority-black suburb in the Chicago area, incorporated in 1917, and one of the oldest incorporated black municipalities in the United States. African Americans were initially relegated to the area to maintain segregation within the two suburbs. Marketing of the area to African Americans provided one of the few opportunities for families to own their homes, with lots costing as little as $90. In the 1950s, 22% of the homes lacked indoor plumbing, and in 1960, over 40% were considered substandard. Considered a slum to outsiders, it was a community of dreams for those who achieved homeownership in a time of redlining and other discriminatory housing practices.

At night, it never truly gets dark or quiet. A low vibrating hum and an aura of uncertainty wafts in the air. I sit on the front stairs, with their crackled paint, enjoying the cooler night air. I cannot sleep due to the stifling summer heat pent up in the house, and the humid wind carries the heaviness of the day. I lean back onto my arms and look up. Maple trees sway as the moon peaks in and out of the branches. The redeye out of Midway Airport scars the sky with long slashes of white exhaust. I cannot help but wonder about the destination. It is peaceful watching the limbs sway back and forth in a moment of tranquility. I then realize that when you gaze at the sky, you can be anywhere and be a part of something bigger with hopes of something better.

Blue Island is built on historic soil.

As a proud settler recounts the past:

Where once the shriek of the tortured and the groans of the dying red man resounded during that vicious massacre, there is now peace and quiet. Bones, battle axes, arrowheads, and other relics of the aborigines which have been dug up even in recent year attest the fury of the early battles which took place in this vicinity.

I do not remember being taught this history, seeing any landmarks or memorials honoring this past. The only remnants are town names like Peoria, Pontiac, and Algonquin. A sacred ground churned into progress of industry and contamination, and the inherent struggle of the proud working class who remain.

A literal interpretation of the Painted Turtle story reminds me of a time fishing with my grandfather when I caught a painted turtle. The turtle stared at me while grandpa tried to get him off the hook without hurting him. I never wanted to fish again.

This is such a beautiful folklore tale based on love, transformation, and living an unexpected life. Looking back, I can see why I took the plunge into environmental justice and how sustainability at community levels inspires me. Thank you for taking this journey with me. This adventure with my fellow educators has made a profound impact on how I see the world.

The Painted Turtle[3]

Epilogue

As I work to finish this chapter I am distracted (which happens when my imposter syndrome strikes) and checking emails. Frontline sends an email with a tantalizing “just in case you missed it” announcement about their interactive experience, “Un(re)solved.” I am directed to a website that asks me to “say their name.” A solemn voice prefaces The Emmett Till Antilynching Act, then presents an investigation on whether justice has been served, decades later, on unsolved racial-based murders.

I navigate through the first three stories and at the end of each, I say the victim’s name to remember them. The fourth story is about Alberta O. Jones. In 1965, she became the first female and first African American prosecutor of Louisville, Kentucky. A 34-year-old lawyer and voting rights activist, she was murdered five months after taking the job. Speculation is that she was targeted by a disgruntled defendant or for her civil rights activism. Her case is still unsolved and open as of June 2019. Her remaining family waits for justice.

I listen to the audio of her sister talking about Alberta and her favorite quote, “More things are wrought by prayer Than this world dreams of.” (“The Passing of Arthur,” 1869, l. 415, Alfred, Lord Tennyson).

These words stay with me, and I wonder how much has actually changed with new restrictive voting laws, continued police brutality and institutional racism, and the slow progress of social justice. With my white privilege of being heard within this book, I want another injustice of the past to see the light of day. Remember to say her name, “Alberta Jones.”