4 Module 4: Study skills

Summary – Basics of good study skills

– Create a calendar and keep it updated with required attendance, due dates for assignments and assessments, and planned study time.

– Create a good, consistent study space with limited distractions.

– Ensure you are spacing out your study and not cramming – The vast majority of studies comparing cramming to spaced studying show that the latter is superior both at the time of the exam (9% higher score for spaced studying) and with re-testing one month later (22% higher for spaced studying – that’s two letter grades).

– Consider the best use of your time – Reading the same notes or watching the same lecture over and over are generally not effective ways to study.

– Pay attention and participate in class – If you take just 5 minutes out of a class to check your emails or shop for shoes, you only have to do that ten times to have missed a whole class session.

– Consider finding a study group – it generally works best to study alone first, then to practice in pairs, and review in a larger group.

– Get enough sleep, remember to exercise, and eat properly.

Note-taking

Taking notes is of great value, even if the instructor provides you with quite complete information. Note-taking triggers your memory and helps you concentrate in class. Instructors tend to stress in class the information they think is most important (and therefore, most likely to be on examinations and to be used in future coursework). Ways that lecturers emphasize the most important points are by pausing before and/or after expressing that point, repeating it, using introductory phrases that make clear the value of that particular idea, and by writing it down (Sweet Briar College, 2015).

Check the tutee’s note-taking skills. Are the notes organized? Are the notes complete? Share with the tutee how you take notes. Remind them to review material before class and to review new material soon after class with additional comments for clarification. Help the tutee compare their notes with any recommended or required readings. Some specific tips to share with the tutee include:

- Complete all readings before class to help you integrate that content with what you hear in lecture.

- Ask questions of the instructor to ensure understanding! This includes taking advantage of review sessions, Chat sessions, and other open office hours that instructors use to supplement virtual and in-person coursework.

- Review your notes as soon after lecture as possible; immediate review increases retention.

- Underline key statements in your notes.

- Use margins for coordinating information from readings or other resources with your notes, jot down important concepts or information, or create short summaries of information.

The speaker can provide more information than you can write down. The average lecturer speaks at a rate of 125-140 words per minute and the average note-taker writes fewer than 25 words /minute. Write down key words and phrases, not complete sentences. Use symbols (1 instead of one) and abbreviations (CEH instead of cystic endometrial hyperplasia, L instead of large) whenever possible. If you miss something, leave a space and check with a peer later to get that content. Do not obsess about spelling and grammar; notes are most useful to you when they’re translated into your own words.

Following are some note-taking formats to share.

Outlining

- Topic / main idea

- Major points

- Details

- Major points

Concept mapping – A concept map is a virtual representation of how topics interconnect. Also called mind maps, this concept is well described on the UMN library site.

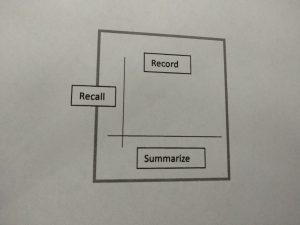

The Cornell System

Using the Cornell system, students write notes during class in the record column and then after class, reduce those ideas into short phrases and highlight major ideas, putting those in the recall column. Then they review these notes and connect main concepts in the recall column with details in the record column. Finally, they jot a few sentences in the summarize section, noting the main points and why they are important. Research shows that students are 31% more likely to remember content by completing all of these steps.

Examination preparation

Here are some proven techniques for review of materials to prepare for an examination:

Flashcards – Students learn from making the flashcards, which requires them to choose and explain important points and concepts, and from reviewing the flashcards. Written rehearsal of content is associated with higher test scores (Judd and Bail, 2006; Kitsantas, 2002; Root Kustritz, 2012). Examples of things to put on flash cards include terms and definitions, facts, formulas, and cycles.

Teaching – Working with a study partner permits students to verbally rehearse the content.

Evaluation of course materials – The peer should check the learning objectives for the course and (if available) for individual sessions and should identify the main points stressed by the instructor. If previous examinations or sample tests are available, the peer can work through them and take time to go over the questions not answered correctly.

Predict questions likely to be on the examination – What were the main points stressed by the instructor? The peer can write test questions based on important concepts introduced in the course and write test questions based on heading and subheading in provided notes or in notes they have taken. Tutees can trade test questions with a study partner and practice answering questions with a time limit.

If a tutee is very worried about an upcoming examination, have them find out about the examination – Is it open book or closed book? Can they use any resources of only the course notes? How much time do they have? If it is an on-line quiz or examination, do they have to take it at one sitting or can they come and go as needed? It is always good to stress good test-taking skills. These include:

- Scan all items before starting.

- Check the directions and follow them carefully.

- Answer the easy items first – Feel free to skip ahead.

- Hunt for key words to help identify information you know well.

- Return to unanswered items and use your best judgment.

- Do not go back over questions and change your answers multiple times – your first decision often is your best decision.

There are some specific strategies for taking multiple-choice examinations.

- Read the stem first and translate it into your own words.

- Hunt for words like “not”, “always”, and “except” to make sure you’re reading it correctly.

- Look for technical flaws that may lead you to the answer, for example use of the same word in the stem and in a foil (possible answer), or one foil being much longer than the others.

- Consider all the foils and cross out those you are certain are incorrect.

- Select the best of the remaining options. Trust your judgment!

If you are helping someone who did not do well on an examination, help them consider reasons for the difficulty. Did they miss class or neglect to do some of the readings? Did they take notes or just study the notes that were provided? Did they run out of time when taking the test and if so, can they pinpoint why? Did they focus on studying content that wasn’t on the examination? What level of thinking were they using – were they just memorizing things or were they learning the material more deeply?

Effective listening for learning

If the person with whom you are working seems to be having trouble concentrating in class or in your coaching session, here are some tips you can share with them:

- Screen out distractions as much as possible – If it is an on-line session, wear headphones or earbuds and do not sit somewhere with visual distractions. For in-person sessions, if the room is noisy, sit near the front. If the speaker has an accent, make sure you have printed notes in front of you to reference in case you have trouble understanding. If the speaker has annoying habits (waving their arms or jingling change in their pockets), do not watch them while they’re speaking.

- If you find yourself daydreaming, find a way to maintain alertness. Do something with your hands to help you pay attention, for example, taking notes. Organize the information as it is presented into main ideas and supporting details. Generate questions (in your mind or on a sheet of paper) to ask the speaker, or that you think might be on an examination.

- If you find yourself responding emotionally, be aware of this emotion and consider how best to address it.

- Listen actively – Summarize material as it is presented. Try to predict what the speaker will say next. Compare things you’re hearing in lecture with things you read in a textbook or other resources, or with material from other courses.

- The more you think about what you hear, the more you will understand and remember.

Metacognition

Metacognition is thinking about one’s thinking and learning. When students apply three specific metacognitive skills to their study, they are better able to create an efficient method for learning that meets their specific needs. These three steps are planning, monitoring, and adapting. Asking students to plan for their study or examination, consciously think through how they did, and then alter their plan for improvement is a powerful way to help them take control of their learning.

One study demonstrated a simple way for students to boost their efficacy in learning using principles of metacognition. Students that used this four-question technique performed better on examinations and reported increased understanding and enhanced memory of the material. The four-question technique is the following:

After completing an exercise or studying for an examination, students wrote out responses to the following prompts:

- Identify one or more important concepts that you learned while completing this activity or studying for this examination.

- Explain why you believe this concept is important.

- Apply this concept to something from your past experience or coursework.

- Consider what questions you still have about this concept or its relevance.

REFERENCES

- Dietz-Uhler B, Lanter JR. Using the four-questions technique to enhance learning. Teach Psych 2009;36:38-41.

- Judd JS, Bail FT. Secondary students’ strategies and achievement. Acad Exch Quarterly 2006;10:116-120.

- Kitsantas A. Test preparation and performance: A self-regulatory analysis. J Exptl Educ 2002;70:101-113.

- Root Kustritz MV. Effect of attitudes toward study, study behaviors, and use of study aids on successful completion of the certifying examination of the American College of Theriogenologists. Clin Therio 2012;2:467-471.

- Sweet Briar College. Note taking skills. Available at:http://sbc.edu/academic-resource-center/note-taking-skills. Accessed 08-13-15.