6 Shared Decision-Making & Adherence

Margaret Root Kustritz

SHARED DECISION-MAKING

“In the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too) those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.” – Charles Darwin

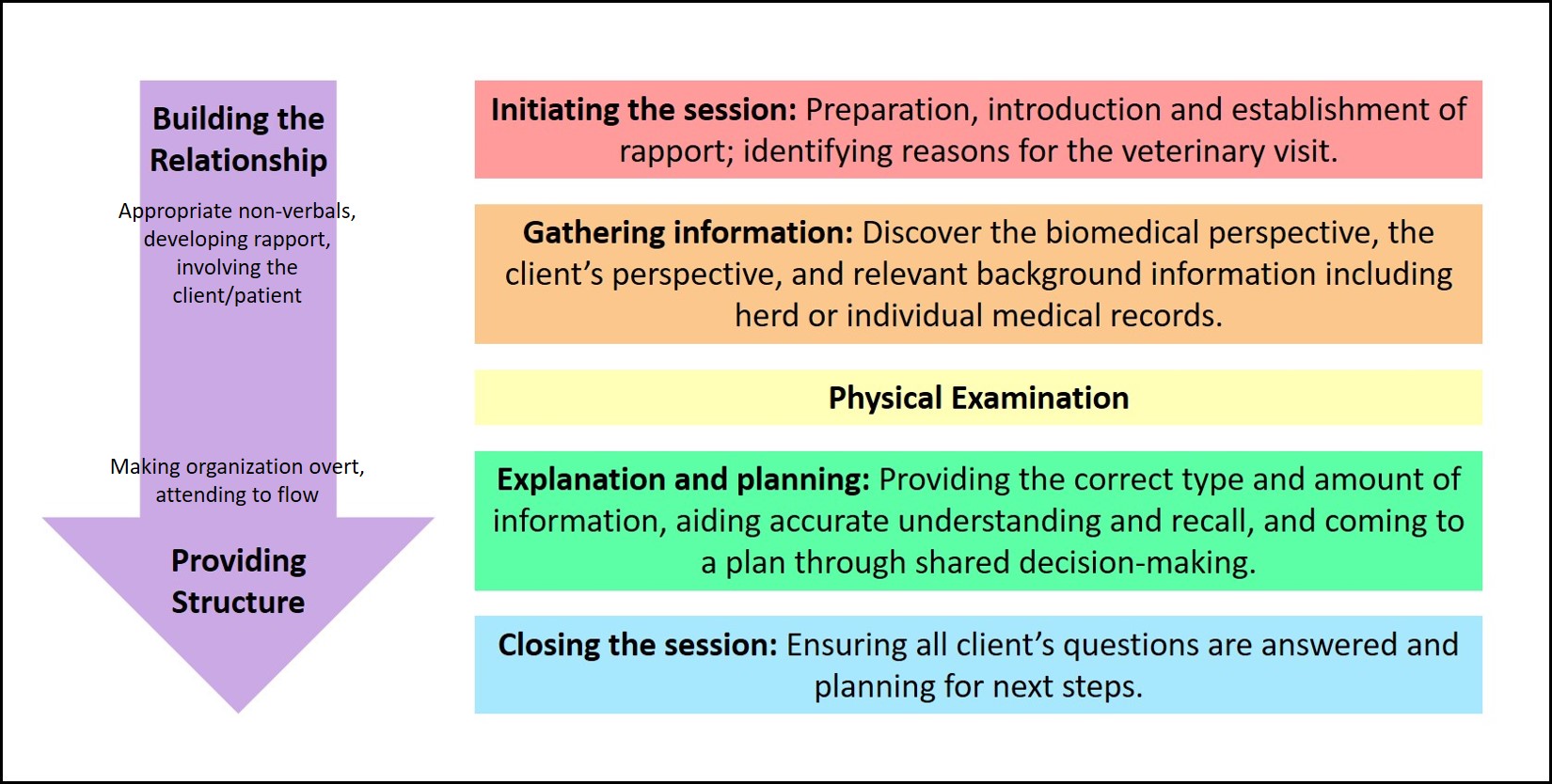

Once you have established a working relationship with your client and gathered some information by taking a history and completing a physical examination, it’s time to think about how to present information to that client so an eventual diagnostic and treatment plan can be reached for the animal or herd in question. Information from this module pertains to building the relationship with the client, as described graphically below:

From the minute you step onto that farm or enter that exam room, you are projecting an image of what relationship you wish to have with that client. One author describes four possible models of the relationship between the healthcare provider and client:

- Paternalism (veterinarian as guardian) = the doctor has much control and the client has very little control. The doctor controls the conversation from the outset, makes all the decisions about diagnosis and care, and expects the client to follow instructions. Can you think of an instance where this kind of relationship is desirable, or even necessary?

- Consumerism = the client has much control and the doctor has very little control. An aggressive or very well educated client makes demands and it is the path of least resistance for the doctor to go along with the client’s agenda. This is sometimes referred to as “treating the client.”

- Laissez-faire or default (veterinarian as teacher) = neither party chooses to take control or responsibility. This is a very ineffective model, as there is little impetus for any plan to be created or enacted.

- Mutuality (veterinarian as collaborator) = both parties have control. Client’s questions and needs are actively sought out by the doctor and the doctor’s thought process is actively sought out by the client. This is also described as a “meeting of the minds” and is the basis for adherence, as will be discussed later.

Shared decision-making arises when there is mutuality, or when the veterinarian takes on the collaborator role. This requires interaction between the veterinarian and client such that they share all stages of the decision-making process. It is perfectly acceptable in this model for both the doctor and client to have strong preferences, but those preferences are put out on the table for discussion, not unilaterally applied. In the final analysis, as the owner it is the client that makes the final decision. If there has been open communication and discussion, the veterinarian can and should clarify the decisions made and the potential consequences of those decisions, and note these in the medical record, which is a legal statement and reminder of the conversation that occurred.

Before we go on, let’s take a minute to talk about the various communications models we present here. This manual will introduce you to many different models, all of which have unique acronyms. You are not expected to memorize these acronyms as their rigid use obviously would lead to unrealistic and stiff conversations. However, it is valuable to have these in the back of your mind, especially for conversations that are not going well.

One system that exists to help us best understand how a client wishes to receive information is the DISC system (FRANK communications, Pfizer Animal Health). It is similar to Meyers-Briggs in that it is based on observations of client preferences for communication in a given situation and that there are not “right or wrong” personality types. To use this system, first observe the client’s non-verbal behaviors and conversational style and then reflect back what you see – “Mrs. Jones, it appears to me that you’re very anxious about the time this appointment is taking and don’t want a lot of detail about how we’re going to move ahead with fixing Ginger’s vomiting problem. Is that correct?” Sometimes the person will be a “D” and that’s absolutely correct. Other times, they’re just excited to show you their new watch and they’re really an “I” who was looking for an opening to talk about it and build a relationship with you.

The four types, their characteristics, and how best to work with them are shown below:

| TYPE | CHARACTERISTICS | COMMUNICATION STYLE |

| D – dominant | These clients are very direct and decisive. They are efficient. They are motivated by solving problems and getting results. They ask “what” questions – “What is the problem,” What are you going to do,” etc. When they are stressed, they give orders and get very intense very quickly | Provide general information quickly and make sure they understand the tasks that need to be accomplished. |

| I – influencing | These clients are talkative and emotional. They are very people-oriented and need to build good rapport with you. They are motivated by persuasion and ask “who” questions – “Who will be the one performing the procedure,” etc. When they are stressed, they get emotional. | Build rapport and give clear explanations of what will be done and by whom. |

| S – steady | These clients are very dependable and accept change slowly. They are very calm. They are motivated by a consistent, organized plan. They ask “how” questions – “How will this medication solve the problem,” “How frequently do I change the bandage,” etc. When they are stressed, they give in and may become accusatory. | Provide specific information at a slower pace. Provide information about risks and benefits. |

| C – conscientious | These clients are cautious and are perfectionists. They want things to be accurate. They are serious. They are motivated by demonstration of high standards and high quality and ask “why” questions – “Why is this considered the best treatment,” etc. When they are stressed, they question and may become unexpectedly emotional. | Provide specific information and facts. These clients like to know that you’re using evidence when determining a course of action. |

Research suggests that people can manipulate only about four unfamiliar variables when making a decision. Research also suggests that we use our conscious brain to take in information about those variables and prioritize it, but that it is our subconscious brain that actually makes decisions for us. People vary widely in their ability or desire to make decisions quickly and as a veterinarian, you must include information about the need for a quick decision into the conversation. People can take all the time they like to think about whether or not to use their dog for breeding but if he has a testicular torsion, a decision about treatment must be made immediately.

To help clients make wise decisions, we need to make sure we’re explaining things fully and at a level the client can understand. One technique is the three-stage explanation technique, briefly described as telling what something is, then what it does, and then how it works. Here is an example of explaining a complete blood count[1]:

- What is it – A CBC, or complete blood count, is a routine test of the various cells in the blood, especially the white and red blood cells.

- What it does – The CBC measures the number of these cell types and determines if they are normal or abnormal.

- How it works – Knowing the number and types of cells permits me to determine if infection or anemia is present.

It may seem redundant to provide so much information, but it is wrong to assume that clients know much medical information. If you’re not sure, just ask – it is perfectly okay to ask someone if they’d like an explanation of the specific blood tests you’re recommending. Some will have a medical background or will have had these tests done before and will tell you they’re okay with no explanation; others will be very happy to be given that information to help guide their decisions.

Not all clients desire a collaborative arrangement. In human medicine, it has been shown that older patients, less educated patients, and patients with more serious illness often prefer the less participatory role present in a paternal relationship. In veterinary medicine, clients may prefer this is if they’re unwilling to show their lack of knowledge or skills, or if they don’t like making choices. We have no way of knowing whether or not our clients wish to be a part of the decision-making process so it’s always best just to ask. It’s also important to note that the client’s wishes may change over time so you need to periodically verify with the client what their preferences are. Dr. Root provides us with an excellent example of this: “I once had a client present a bitch who had been bred by accident. She did not want the bitch to have pups and so brought her to me initially for pregnancy termination. The bitch was at a stage of gestation where ultrasound would have been the only accurate diagnostic tool and the owner did not want to pay for that, so I had to tell her I could not definitively diagnose pregnancy in her dog at that visit and would need to see her back in about a week. She was not happy that I wasn’t able to answer her question. I asked her if she wanted me to explain to her the accuracy of various pregnancy diagnostic techniques; she did not. I asked if she wished me to present her with a plan for the future for this dog; she did not. She chose to come back about two weeks later and by that time, everything had changed. She had decided that pups from this male would be okay and suddenly she wanted to know everything I could teach her about pregnancy in bitches and very much desired a more collaborative approach to her bitch’s care.” In the final analysis, the role chosen must be the one that best permits us to relate to the animal and owner effectively and confidently at that time, and that does not lead us into unethical personal or professional behavior.

ADHERENCE

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health provider”.[2] Professionally, we translate this into a client’s ability and willingness to provide the recommended patient care is carried out.

There are numerous benefits that correspond to increased adherence that include improved health of the patient as well as increased satisfaction of the veterinarian.

Evidence identifies specific tasks and skills that build trust and improve adherence. These include inviting the client perspective, emphasizing the value of the recommendation, linking the recommendation to the client’s perspective, and follow-up. In addition, using the core skills of open-ended questions, making reflective statements, offering empathy, and asking permission work to build trust. Communication is the highest predictor of adherence. Nearly 7 out of 10 pet owners with a strong bond with their veterinarian said they ALWAYS follow their recommendations.[3]

Strategies to Improve Adherence

- Use core communication skills

- Seize opportunities to offer empathy

- Chunk-n-check

- Ask-tell-ask

- Use clear and simple language

- Build credibility

- Ask client opinions

- Restate client’s perspective and link to the recommendation

- Know your client and tailor to their needs

- If you don’t know, say you don’t know (and find the answer)

- Use resources (brochures, staff assistance)

- Demonstrate the desired behavior

- Follow-up

At this point, we have gathered information from the history and from review of past records, and have completed the physical examination. Now, we need to review that information for the client and, with whatever degree of collaboration they desire, arrive at a shared plan for diagnosis and treatment. The client must be convinced the diagnostic and treatment plan is appropriate and confident they can carry it out (technically and economically) if they are going to adhere to the plan. Adherence is the degree to which clients carry out this shared plan; it is differentiated from compliance, which is the degree to which clients carry out a plan mandated by the veterinarian. One author[4] states that adherence requires you recognizing and addressing the client’s concern (coughing) versus your concern (heart failure) and notes that “(t)he most wonderful, state-of-the-art medical science and technology has no value if it results in a treatment the owners find unacceptable for any reason”. A survey of client compliance in Trends magazine in 2009, published by the American Animal Hospitals Association (AAHA), showed that client adherence to recommendations regarding routine healthcare rose by 9% from 2003 to 2008. One acronym recommended by AAHA to help veterinarians ensure compliance is CRAFT: Compliance = Recommendation + Acceptance + Follow-Through. This idea stresses the importance of how input from the veterinarian and veterinary staff at the hospital and client cooperation are required.

Before discussing in detail the explanation and planning stage of the veterinary visit, let’s take a minute to talk about record keeping. All the information gathered from the history and physical examination must be recorded at some point. It is tempting to write everything down as you find it, or to enter it into the computer as the client is speaking. However, you must continue to pay attention to the client to maintain the rapport you’ve worked to build to this point. It may help to signpost, which is to overtly tell the client what is happening in the appointment by drawing their attention to what you’re telling them or doing. This could be as simple as telling them that you need a second to write down physical examination findings, especially numerical things like weight and rectal temperature, before you forget them. If you’re using a computer, remember not to turn your back on the client as you work on the computer and make sure you’re making eye contact with the client and not just staring at the computer screen. Make sure you know the computer program well so you don’t have to spend excessive amounts of time hunting through the program. If you can’t touch type (or finger peck with great speed), don’t try to enter lots of information while the client watches you struggle. Finally, if you wish to use the computer to demonstrate things to the client such as lab work or radiographs, make sure you’re very comfortable getting to that information on the computer before doing it in front of a client. Of course there are always malfunctions that arise and the ability to handle those bumps in the road and continue to maintain conversation/ build rapport or shift gears while things are being fixed is an invaluable skill, as well.

Explanation and planning is described by[5] as the following scheme:

- Provide differential diagnoses or hypotheses regarding what is causing the clinical presentation.

- Describe plan of management, including diagnosis and treatment alternatives.

- Assess the client’s understanding and negotiate a plan of action.

To accomplish this scheme, you must first present the information you’ve gathered and how you’ve interpreted that data. Present it in a logical manner so the client can “hear” your train of thought. It also may help to signpost again (“On physical exam, I noted two problems I think are part of Flasher’s problem today, a swelling on the hock and at the navel. There are three possibilities and I’d like to talk about them one at a time. The first is joint ill, or septicemic arthritis…”). Assess the client’s starting point of understanding (“Have you heard or read anything about joint ill?”). When explaining, periodically chunk and check. That is, provide a small amount of information, make sure the client fully understands it, and then provide more information. Avoid giving advice or prematurely reassuring the client if they’re concerned (Do not say, “I’m sure antibiotics will cure it.” Instead say, “Let’s talk about what tests we need to do to help determine which antibiotic is most likely to be effective for this type of infection”).

Make sure the language you use is not so simplistic as to be demeaning to the client but not so technical as to be over their head either. Obviously, this varies with the client. Clients are unlikely to tell you they don’t understand so it helps to learn to recognize signs that they’re not understanding. Practice this on a child sometime and you’ll learn how to recognize the wide eyes and nodding of the head that demonstrate lack of understanding and unwillingness to admit that. Sometimes it helps to ask the client to restate something in their own words, to assess how well you explained a test or treatment plan.

Make sure you’re negotiating a plan. That requires you to ask specifically for their input and to be open to their thoughts. Kurtz[6] describes this as the “accepting response.” Acknowledge their concerns or thoughts (“So you’re worried this may have been caused by feeding the mare too rich a diet late in pregnancy.”). You’re not necessarily agreeing with it, just acknowledging it. Make sure you permit the client to state their concerns or questions completely. When you respond to it, avoid using the word “but.” If you say, “Well, I understand your concern, but…” it automatically negates the first part of that sentence. Get in the habit of responding in a consistently positive way, such as, “I understand your concern. Let’s talk about what we know about how this problem develops in foals”.

For the client to believe you’re willing to negotiate a plan with them, you must demonstrate concern, willingness to help them come up with a workable plan for them and their family, partnership to see the problem through to completion, and sensitivity for their concerns, even if you think they’re unfounded. The AVMA liability insurance trust constantly tells us it is unsafe to let clients restrain their own animals in the examining room or on the farm. This may take away your ability to judge a client’s ability to work with that animal. If clients do not adhere to a plan, it usually is not because they don’t trust your judgment as a veterinarian. Common reasons include:

- money

- forgetfulness, especially as the animal improves

- public health concerns

- packaging, size or taste of the medication

- side-effects of the medication

- difficulty scheduling nursing care, physical therapy, medication

- inability to perform the care or treatment recommended

- disbelief that it is what is needed at this time

Helping the client recall what you’ve talked about can be a daunting task. A student one year described this as helping clients create a memory. Techniques that have been demonstrated to help include:

- telling clients what category of information you’re providing (“Now let’s talk about diagnostic tests for this swollen joint.”)

- telling people the most important thing first – this is called the primacy effect – and repeating the most important thing last

- telling people that something is important (“This is important; do not forget to give the antibiotics as described, as missed treatments will prolong infection and increase risk of permanent joint damage.”)

- asking the client to restate information in their own words

- providing materials, including written information, diagrams, and/or pertinent websites

- Tri-telling = providing information in three different ways (describe antibiotic treatment verbally, point out the written instructions on the medication bottle, ask the client to repeat the instructions for you)

- enlisting the technical staff and receptionists – the client may be more willing to ask them a “dumb” question than to admit ignorance to the veterinarian

It is sometimes difficult to balance providing the client with clear information and overloading them. There is much research suggesting that when presented with too many options, we undergo decision paralysis and oftentimes choose something with much less care and thought than we would had fewer options been available. Be aware of your own decision-making process and make sure you’re providing options that are in the best interest of the client and the patient. Be aware that the process of offering options and discussing the pros and cons of each will create some level of anxiety for the client, as there is rarely any single best choice. It has been shown that people need the most help making decisions when the decision they’re making is one that is rarely made, for which they may not get prompt feedback to know if it was the right decision, and if they have trouble understanding all aspects of the decision. That will be the case with most decisions you help your clients make in veterinary medicine.

Clinicians in the General Practice service often say that inability to confidently make recommendations for diagnostic testing or treatments is the most common communications weakness in students on that rotation. It is valuable to learn to speak confidently regarding what you think is the best option but you also need to remember that not everyone will agree that that is the best option because of cost or other concerns. Many communications with clients are in regards to preventive care and there is a growing push for all of us to better present that information to clients and to make them aware of its value. In one study, it was demonstrated that clients who received a clear recommendation were 7 times more likely to act on that recommendation than were those clients who did not hear a clear recommendation.

Once you and the client have come up with a plan for diagnosis and treatment, it’s time to close the veterinary visit. The objectives are:

- To confirm the plan of care.

- To clarify the next steps for the veterinarian (“I’ll call you with lab results as I get them”) and the client (“You’ll be starting the hydrotherapy that we discussed right away”).

- To establish contingency plans (“If Flasher seems to get worse, call this emergency number any time”).

- To close the episode to the client’s satisfaction; this last step involves summarizing briefly and asking one final time if you can answer any questions or address any further concerns.

It is best to get client consent to procedures and to create a written estimate. The AVMA gives the following guidelines regarding informed consent: “Owner consent better protects the public by ensuring that veterinarians provide sufficient information in a manner so that clients may reach appropriate decisions regarding the care of their animals. Veterinarians, to the best of their ability, should inform the client or authorized agent, in a manner that would be understood by a reasonable person, of the diagnostic and treatment options, risk assessment, and prognosis, and should provide the client or authorized agent with an estimate of the charges for veterinary services to be rendered. The client or authorized agent should indicate that the information is understood and that they consent to the recommended treatment or procedure.”

- Walters, MJ. (2010). Communication skills for medical professionals. Walters and Worth. ↵

- https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y ↵

- null ↵

- Milani, M. M. (1995). The art of veterinary practice: a guide to client communication. University of Pennsylvania Press. ↵

- Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2005). Skills for communicating with patients. Radcliffe. ↵

- Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2005). Skills for communicating with patients. Radcliffe. ↵