1 Communication Matters

Margaret Root Kustritz; Emily Barrell; and Kara Carmody

Effective communications build rapport between the veterinarian and client, enhance client adherence in veterinary recommendations, decrease malpractice claims against veterinarians and, in general, improve quality of veterinary care provided. The four essential components of clinical competence are knowledge base, physical examination, communication skills permitting gathering of an adequate history and explanation of appropriate diagnostics and treatment, and problem-solving ability. There are three broad types of communication skills:

- Content skills = what information is communicated by the veterinarian

- Process skills = how the veterinarian goes about collecting and providing information

- Perceptual skills = how the veterinarian’s attitudes and internal thought process interact with their innate knowledge and the information they gather from the patient and client

The focus of this communication curriculum is less about what to present (content skills) and more about how to gather, process, and disseminate information in an efficient and consistent manner. This is presented to you now to give you a basis in communications training that you can use while in veterinary school and, hopefully, in your future career.

Pfizer Animal Health, in their training course, describes two approaches to communications. You will see as we go through the material that both approaches have their place.

| Shot-Put Approach | – A well-conceived, well-delivered message is all that matters.

– The emphasis is on telling, not on client dialogue. |

| Frisbee Approach | – The two central concepts are (1) confirmation = recognizing and acknowledging each other, and (2) finding mutually understood common ground.

– The emphasis is on interaction. |

Much of the following information arises from the work of Silverman, Kurtz and Draper[1]. Effective communication is defined by these authors by demonstration of the following characteristics:

- There is not just one-way transmission of information but rather an interaction, ensuring creation and maintenance of a veterinarian-client-patient/animal relationship (VCPR) as is required by law and necessary for optimal animal care.

- All uncertainty that can be removed, is removed. The client’s questions are answered. The veterinarian’s need for accurate and complete background information is fulfilled.

- Planning is required for both parties to achieve desired outcomes.

- The situation is dynamic; as the needs of the animal, client, and veterinarian change, so must the communication.

- It is not linear but is instead helical, with communication evolving as the interaction occurs.

When gathering information, make sure to get the biomedical perspective (what signs is the client seeing, what is the sequence of events, have they treated it and how did that work, how are the other systems in the animal working); the client’s perspective (pain assessment, specific concerns based on their prior knowledge, concerns about cost or ability to provide appropriate care for the animal), and relevant background information (herd records, individual medical records especially if you’re not the primary veterinarian for this animal or farm, medication history, physiologic state [pregnant, lactating, performance], husbandry information). As you collect information, periodically summarize it – that way the client knows you are listening and you know you are taking in the information correctly so you and the client can achieve a mutual ground from which to make decisions.

When you think you’ve gathered all the relevant information, take time to deliberately check for other concerns. One of your colleagues likened this step to that of a computer checking if you really want to shut down so you don’t lose any programs or saved material. This should again be open-ended (“I agree that it sounds like hardware disease. Before I check her over, is there anything else going on with this cow or the milking herd that you want to talk about today?”). This prevents a rude surprise, such as when you’re just about ready to drive off the farm and the client leans in the window of the truck and says, “Hey, Doc, I wanted to mention, I’m having the worst problem with calf diarrhea…” The study cited above demonstrated that clients were 4 times more likely to bring up a new concern at the end of the appointment if it had not been addressed than if the veterinarian had asked about other concerns much earlier in the conversation.

It may sound like this would take an inordinate amount of time. Research has shown that physicians that use these techniques may spend more time in the exam room with the patient during the initial exam but often spend less time later on because all of the patient’s concerns are addressed early in the process. If you have a limited amount of time to spend with a client, some things you can do to make sure the client does not feel short-changed and rushed through the encounter are:

- Pause and make eye contact before you speak. Give the client your full attention and don’t look at your watch or the clock on the wall.

- Be clear about time constraints but frame them in a positive light. Don’t say, “I can only talk to you for about 5 minutes.” Instead say, “I have 5 minutes for you right now and if that’s not enough, let’s make sure to schedule a time before you leave to talk again.”

- Sit down to hold the conversation. Conversations held when standing, especially if you’re standing in a doorway or the open door of your truck, are perceived as less genuine.

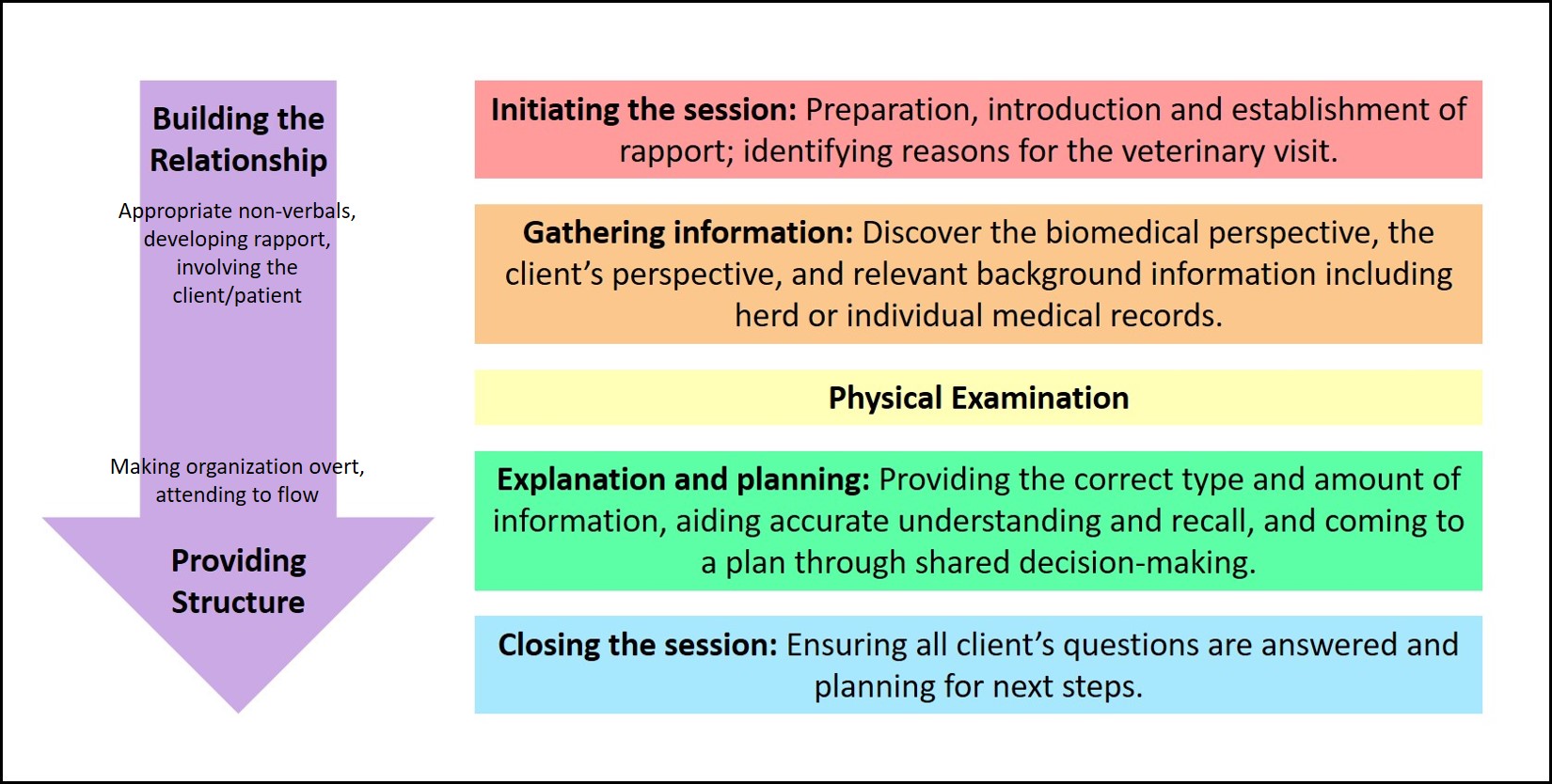

Silverman, Kurtz, and Draper[2] break the process of interacting with a client into steps as shown graphically below:

One author[3] describes learning how to interact with clients by utilizing the Four Habits:

| HABIT 1 =

INVEST IN THE BEGINNING |

Create rapport; elicit the client’s full spectrum of concerns using open-ended questions, continuers, and re-completers; plan the visit (“Now that I’ve got the history, I’ll do a physical exam and then we’ll talk about what tests might be necessary.”) |

| HABIT 2 =

ELICIT THE CLIENT’S PERSPECTIVE |

Show respect for the client’s knowledge; compare differences in your understanding and theirs to make sure you’re all on the same page |

| HABIT 3 =

DEMONSTRATE EMPATHY |

Use reflection and legitimization; show respect for their concerns even if you know they are not grounded in fact. Make sure the client knows you care but do not become so engulfed in their situation that you are unable to use professional judgment. Good phrases to use for reflection include, “So you are saying…,” “It sounds like…,” “Are you wondering…,” and “Are you feeling…” When making empathic statements, name and appreciate the owner’s predicament or concern and strengthen your statement with appropriate nonverbal communications. Insincere expression of empathy is worse than none at all. |

| HABIT 4 =

INVEST IN THE END |

Deliver information in a way the client can understand; share decision-making; check for client understanding. Summarizing information or the plan going forward, and signposting to make sure the client is following your thought process, are very valuable. |

So far we’ve talked primarily about communications when working with a client who brings a companion animal into your facility. Working with production animals requires many of these same skills with some additional considerations:

- Decisions may be based on the client’s working capital, not on discretionary income.

- You should consider the economic value of an animal and, if it’s a food animal, include information about withdrawal times for milk and meat into all decisions about treatment.

- Large production facilities are owned by entrepreneurs. It has been demonstrated that owners of these large facilities want the following from their veterinarians[4]:

- Recognition of the farmer’s professionalism

- Focus on the market

- Cooperation with the farm’s organizational structure

- Good communication skills including active listening, ability to summarize discussions, and cooperation in decision-making

- Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2005). Skills for communicating with patients. Radcliffe ↵

- Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2005). Skills for communicating with patients. Radcliffe ↵

- Adams, C. L., & Frankel, R. M. (2007). It may be a dog's life but the relationship with her owners is also key to her health and well being: communication in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 37(1), 1-17. ↵

- Noordhuizen, J. P. T., Van Egmond, M. J., Jorritsma, R., Hogeveen, H., Van Werven, T., Vos, P. L. A. M., & Lievaart, J. J. (2008). Veterinary advice for entrepreneurial Dutch dairy farmers: from curative practice to coach-consultant: what needs to be changed?. Tijdschrift voor diergeneeskunde, 133(1), 1-5. ↵