14 Difficult Client Situations

Margaret Root Kustritz and Emily Barrell

“The greatest remedy for anger is delay.”

– Seneca

Difficult client interactions are those conversations that take place outside of the comfort zone of the veterinarian and/or the client. Patterson et al would include these in “crucial conversations,” defined as discussions characterized by high stakes, strong emotions, and varied opinions. [1] Specific examples in veterinary medicine include discussions about serious illness, money (especially for clients who cannot afford the care they wish they could provide), euthanasia, and ethics. This discussion is not about difficult clients (people) but rather difficult client situations (experiences).

When confronted with a situation, humans respond using one of two basic systems, sometimes termed the “hot” or “go” system and the “cool” or “know” system.[2] The “hot” or “go” system is a vernacular term describing our “fight or flight” mechanism – cortisol is released, blood flows from the brain to the arms and legs, heart rate and blood pressure increase, and the amygdala (sometimes called the “reptilian brain”) takes over. This part of the brain is responsible for quick, emotional responses, not deep thought.

The “cool” or “know” system is designed for higher-level thinking. Because it operates more slowly, it is not in use during times of high stress or what our mind perceives as danger. However, this is the state you need to be in to be able to handle difficult conversations calmly and effectively. As you might imagine, it is valuable to be able to turn off that “lizard” brain at will. This can be accomplished by calling on your brain to complete an activity impossible for the amygdala. Here is another of Dr. Root’s real-life examples:

“I was seeing cases on a busy afternoon. I was very tired, as I had seen a case in the middle of the night; that dog had serious uterine disease but the owners refused treatment. The dog had died that morning and I was feeling weary and unhappy about the whole experience. Suddenly, the clinic door burst open and a teenaged woman rushed in. In front of a packed waiting room full of people, she pointed at me and shouted, “You killed my dog!”

My first impulses were to shout back, “I did not!” or “Who the heck are you?” Instead, one of the technicians escorted her into an exam room and I took a minute to cool down my flushed face and angry brain by figuring out who she was and why she was mad at me. She was, of course, the daughter of the people who had refused treatment. She was really angry with them but was taking it out on me. Thinking that through calmed me down enough to be able to go in and have a conversation with her about what had happened to her dog.”

To control your own anger when you’re in a difficult situation, take a minute to consider how you might respond and then think about your physical awareness (what can I do physically to calm myself down), your emotional awareness (am I mad at this person or this situation), your consequence awareness (if I respond as I’m thinking about, what will be the consequences), and your solution awareness (is this the only solution available). Taking time to think will move you away from the control of your “lizard brain.”

How do you know a client is getting agitated? Sometimes it’s very easy to tell. More subtle signs that a person is not communicating logically are frequent interruption; repeating statements, especially with increasing volume; and falling back on trite phrases with no meaning (That’s just the way I do it, or That’s our policy).

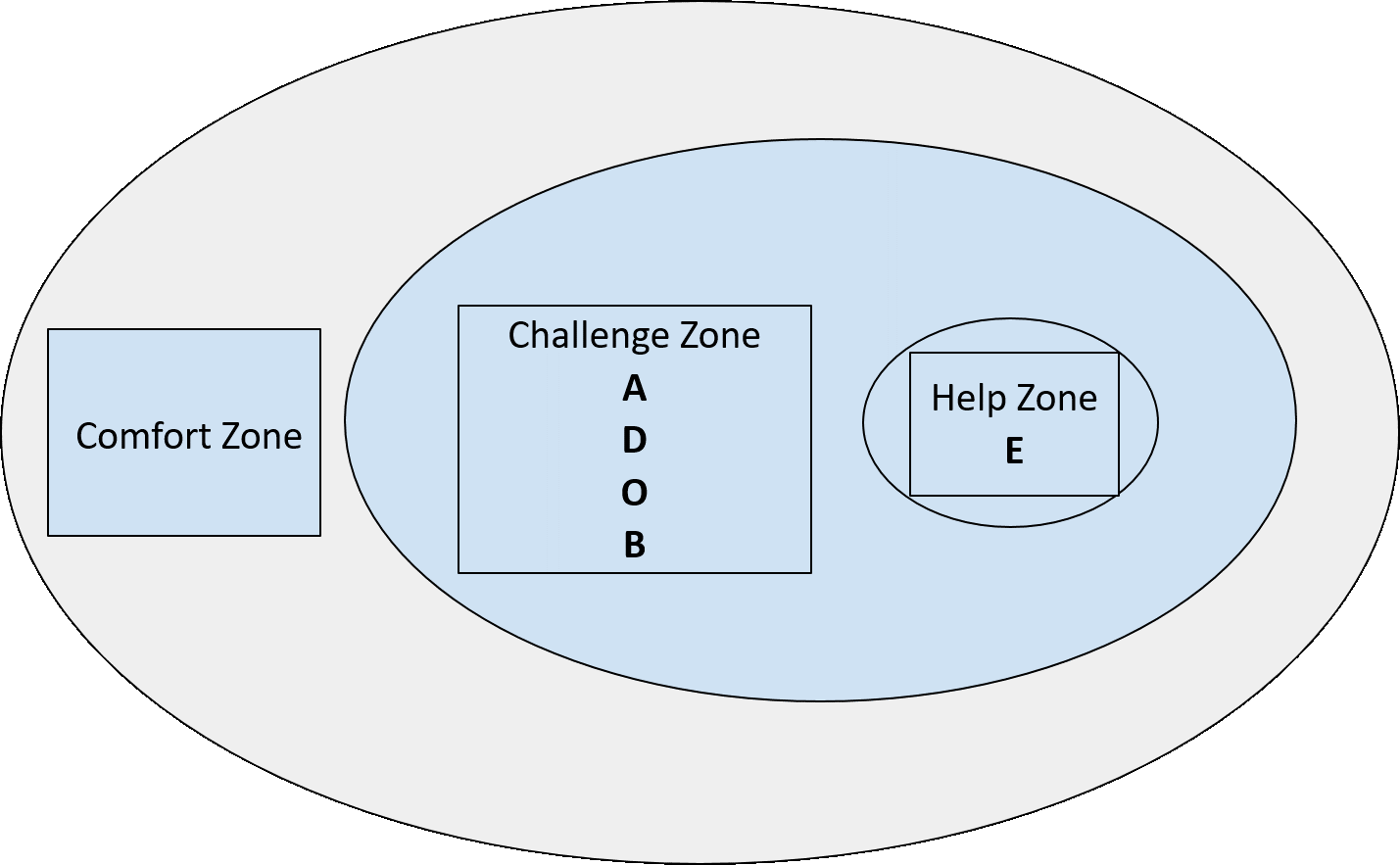

One model that can be used to think through how to handle clients under the influence of strong emotion is the ADOBE model.[3] For a mental image, you can think of how an adobe building would protect you, the same way that use of this model may protect your boundaries as you work through the difficult conversation. The ADOBE model is:

A = acknowledge the problem

- Let the client know you’re aware that things are not going well.

D = discover meaning

- Find common ground. Ask them specifically which of their expectations were not met.

O = opportunities to show compassion

- Acknowledge where they may be right. This can be hard to do – pick your battles wisely.

B = boundaries

- You can acknowledge that someone else is disappointed without compromising your principles. Be clear of your boundaries regarding time, your need to be paid, what language you’ll listen to, and which procedures you will or will not do.

E = extend the system

- Make sure you know if help is available. A severely depressed client may need a human mental health care worker. A farmer whose cows are suffering from metabolic diseases may need the help of an outside consultant, such as a nutritionist.

This can be described graphically as demonstrated below:

Most of the time, we’re in our comfort zone. Sometimes we’ll enter the challenge zone when dealing with a client; at that point, it’s important to acknowledge that communications are breaking down and decide either to take a break for a bit or to address it. Finally, there may be some interactions you do not have the tools to complete, through no fault of your own. This is the help zone.[4]

When a client is addressing you with anger or confusion, make sure not to ignore or dismiss their question. One author likens this to judo; when confronted with physical violence, the idea in judo is not to block it but rather to redirect it and use that energy to a positive end.[5] He suggests that you use questions as opportunities to explain yourself and to educate that person. Use empathy to help relieve tension. Paraphrase what the client is telling you, making it clear to them that you are the one who needs time to have a clear understanding. Finally, learn to respond, not just to react with your reptilian brain.

There are basically five ways to approach conflict. This is useful to consider both for understanding the client’s viewpoint and for determining how and when you will respond. No one of these is the best way to approach conflict. The five approaches are:

- Avoiding – the primary goal is to delay

- Accommodating – the primary goal it to yield

- Competing – the primary goal it to win

- Compromising – the primary goal is to find middle ground

- Collaborating – the primary goal is to find a win for both sides

It also can be useful to think about exactly how the client is expressing something when you consider how to respond. One author describes ten ways in which language is used inappropriately.[6]

The table below summarizes them, gives examples, and provides a clarifying question you can ask to redirect the conversation in a more productive way.

| LANGUAGE PATTERN | EXAMPLE | CLARIFYING QUESTION |

| Deletion | I’m disgusted! | By what or whom? |

| Vague pronoun | They say all cats that get vaccinated get cancer. | Who says that? |

| Vague verb | Your technician made me lose. | What exactly did the technician make you lose? |

| Nominalization | I’m feeling regret. | What are you regretting? |

| Absolutes | I’m always made to wait while others go ahead of me. | That has happened every time? How can we make sure to track that? |

| Imposed limits | You must cure her. | Can we talk about what will happen if I can’t cure her? |

| Imposed values | All veterinarians are in it for the money. | Why do you think that? |

| Cause and effect error | You’ve made me very angry. | What have I done that you’ve been unhappy with? |

| Mind reading | I can tell the receptionist hates me and my cat. | How do you know that? |

| Presuppositions | If I had higher quality genetics, you’d get to my farm faster on emergency calls. | How specifically have we let you down when answering emergency calls? |

Finally, when thinking about difficult conversations, be aware that you are not expected to come to an agreement with the client in every case. If the client is upset about the animal’s condition or the unexpected costs associated with that animal’s care, you can do little to change how they feel. However, you can express empathy and demonstrate willingness to partner with them in finding solutions. That said, it also is important to consider your boundaries, as described in the ADOBE model. Just because a client wants you to give them services for free, or to take their critically ill animal home with you instead of leaving it in the hospital overnight, that does not mean you have to do it to be a good, caring veterinarian.

- Patterson, K. (2002). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when stakes are high. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ↵

- Patterson, K., Grenny, J., Maxfield, D., & McMillan, R. (2008). Switzler. Influencer: The Power to Change Anything. ↵

- Morrisey, J. K., & Voiland, B. (2007). Difficult interactions with veterinary clients: working in the challenge zone. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 37(1), 65-77. ↵

- Morrisey, J. K., & Voiland, B. (2007). Difficult interactions with veterinary clients: working in the challenge zone. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 37(1), 65-77. ↵

- Thompson, G. J., & Jenkins, J. B. Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion, revised ed., 1994 & 2004, Quill. ↵

- McKay, M., Davis, M., & Fanning, P. (1995). Ultimate guide to improving your personal and professional relationships. MJF Books. ↵