5 Chapter Five | “We are the Battery Human”

Linda Buturian

Where are we goin’ this fine morning?What are we doin’ this fine day?We’re doin’ the same as ev’ry morning!We’re stayin’ inside on this fine morning.Stayin’ inside on this fine day.We’ll stare at a screen, like ev’ry morning.

Listen to Stornoway’s “We are the Battery Human” provided with artist permission.

The digital story assignment assumes that an infrastructure of technology is accessible to all students, whether it is a tablet, a camera, and laptop, or more. Educators who are adapting digital stories into their teaching and learning are likely integrating technology into other aspects of their classroom as well, by choice or by decree. Technology’s pervasive reach into our students’ lives and our own, along with its global march and impact, begs for the same thoughtful scrutiny we give to other aspects of teaching.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, “Youth spend more than 7½ hours a day using electronic media, or more than 53 hours a week, the 10–year study says. And because they spend so much of that time ‘media multitasking’ (using more than one medium at a time), they actually manage to pack a total of 10 hours and 45 minutes worth of media content into those 7½ hours.”[2]

My family reflects these statistics. If you took a nickel from me every time my husband and I worried about how much time our daughters were spending on their devices, and if you gave me a quarter for every time we talked with our daughters to establish and maintain technology limits, you would definitely come out ahead.

The immersive nature of technology provides digital storytelling topics and research opportunities for educators and students alike. A topic that seems to be hiding in plain sight though, which I believe is elemental to the changing story of educational discourse, is the direct connection between our use of technology (mobile devices in particular) and its impact on our selves, other people, and living systems.

By applying the Backward Design model to the life cycle of the technologies we use in our classroom, and by allowing that to reveal our paradigms of thought about our relationship to technology, my hope is to help educators and students move from an unconscious use of technology to a more dialectical approach to technology. I use the term “dialectical” to mean holding in a dynamic tension contradictory views of technology. Applying the building blocks of participatory learning—transparency, collaboration, and critical thinking—to this endeavor will help us see the transformative power we as educators, and our students, can experience. Where relevant, this process can shape the scope of the digital stories that students create. Let’s consider the material elements of mobile devices.

“Much of the iPad’s and its competing products’ increased carbon footprint emanates from their need for rare earth metals, or “conflict minerals”, which are critical for these sophisticated devices’ functionality. The iPad and other tablet computers require coltan, the industrial name for columbite–tantalite, a dull black mineral from which even rarer elements are processed. While the recycling of electronics continues to improve, 70% of coltan still comes from mines. Over half of the world’s coltan supply comes from Africa, where many nations like the Congo are either unstable or enduring civil war. One–quarter of the world supply of coltan is from Brazil, and another one–eighth is from Australia, so besides the human costs that come from these mining operations, coltan is transported long distances to regions like east Asia where these devices are manufactured.” [3]

Pause for a moment and picture the number of devices you see in your schools and then imagine that multiplied throughout the United States. Expand globally. On a recent trip to Thailand I learned that the king of Thailand had committed to giving tablets to all second graders throughout the country; the magnitude of the need for conflict minerals is staggering and the impact on communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and elsewhere is devastating.

When I encountered this information, I went through a similar process as my students do when they discover that a water bottle is not only a convenient way to quench their thirst and that a cellphone is not simply a device that entertains and connects students to friends and loved ones. These objects are also cultural, political, economic, gender, and environmental signifiers, linking our lives to people and ecosystems near and far. My response, like my students, is personal and emotional. At first I blocked out the information, tried to minimize it, and then the horror and guilt washed over me at the realization of my part in the reality that women and children in the DRC are being raped and murdered for my smart phone to send messages swiftly and to vibrate when I have a text. As a student activist for the DRC put it, “I’m carrying a piece of the conflict in my pocket.” [4]

The emotional response to this information, and the resulting move to consider one’s personal use of mobile devices, is an important step in transformative learning, as it connects students to global issues in a powerful way. Their natural inclination is to notice what is immediately around them and to do something about it – for example, changing their consumptive patterns. This move is empowering, and this empowerment is at the heart of transformative learning. Students are learning new information and applying it to their living; they go out and tell their friends and the world around them becomes a place that they are connected to and part of. This in turn motivates them to learn more through the digital story process, and to make connections with the information they learn from their research and interviews with experts.

But for those of us teachers involved in participatory education, our responsibility is to work with students to take that personal connection and link it to the political and economic systems as well as the ideologies that shape our society, so that students can analyze the assumptions with the critical thinking skills we are strengthening in order to participate in the process and marshal their academic skills to create more just, sustainable futures.

It appears that I am suggesting adding one more mandate to our overburdened classroom time — that we all teach natural resource justice and resource footprint impacts of technology along with our respective subject matters. I am asserting that by using technology in the classroom without unpacking the global and local implications of the life cycle and energy use of that device, as well as the deeper issues associated with western use of technology, we are already teaching a world view. As educators we are giving our tacit consent to the zeitgeist of our times, a technical colonialism that outsources the cost and suffering and promotes a view of technology as ethically neutral, benevolent, and rightfully ours: these are simply devices for learning and consuming. By handing students tablets and using terms such as “the cloud,” with no unpacking of the reality of energy production, data farms, carbon and water footprints, and impact on workers, communities, and ecosystems from our neighborhoods to the DRC, we are wearing the “black shoe” (Sylvia Plath) of colonialism that our forefathers and mothers used to kick off established complex communities of first peoples.

“You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe”[5]

Can we agree that we are too far down the road in terms of greenhouse gases, resource use, and global awareness of our interconnectedness to perpetuate this kind of education? Our ignorance is a kind of poverty that others can see. This particular naiveté, our lack of awareness about the impact of our use of mobile devices, puts the “ugly” before “American.” Our students deserve more, as do the Congolese.

It is tempting to think it’s not our problem. Individually, we are so small. Shouldn’t this belong to legislators and administrators of school districts and software companies? Yes. (See the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act Systems). There is movement toward conflict–free suppliers, but the progress is glacial. There are tremendous learning opportunities here, and something deeper.

Analyzing our dependence on mobile devices and its ripple effect can be an essential part of modeling citizenship, and an important component of the transformative learning students can experience as they create their digital stories. If we do not integrate this information into our teaching, how will they learn to participate in this elemental part of the changing story? Our futures are intertwined with our students, and we need their generative minds and imaginations and desire to shape more just societies, to design more energy efficient devices, to forge partnerships for conflict free paths from extraction to use. And students are up for it.

It is important for us to help each other and our students move from an unconscious to a dialectical relationship with these technological devices, not simply because it is the ethical thing to do, but because there is tremendous power in knowing and doing, in applying their education to making a positive difference in society. Through transparency, collaboration, and critical thinking, educators and students can grapple with the pervasive impact our devices have, and at the same time utilize these devices to participate in positive social change.

Am I suggesting we use iPads, smart phones, and laptops to create digital stories about the global impact of these devices? Please. And share them with your colleagues. But I am in year 4 as a faculty member participating in a college initiative where all incoming students receive iPads, and while I have made inroads empowering first generation and immigrant students with wise access to technology, reducing students costs, and helping students create compelling art and socially conscious digital stories, I have still not been able to integrate this information widely in the classroom.

The first step for educators is to decolonize our own minds.

We are a part of the zeitgeist of our times. I am as in–webbed as the next. We are “The Battery Human,” members of a society that collude in giving technology power. We make sacrifices of time, money, and energy to it, and therefore it is more powerful than simply a combination of metals, plastic, and energy. Technology is a signifier that outs us yet we are so busy using it we don’t notice.

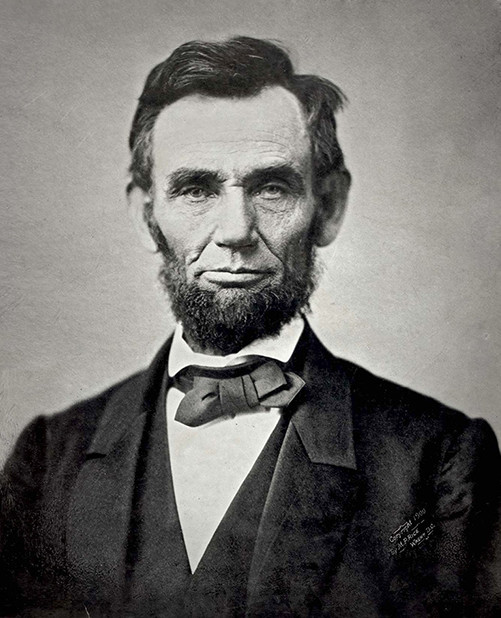

We must, to borrow a phrase from Abraham Lincoln, “disenthrall ourselves” from the western capitalist notions of technology. Through knowledge, dialogue, and action, lift off the “mind–forg’d manacles.”[6] that keep us in ignorance, and deprive us of the power to effect change.

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

Abraham Lincoln, Second State of the Union Address (1862)

This is a daunting task. Spend any amount of time researching and reflecting on the impact of capitalism, and the reach of technology, both, combined, create a hegemonic hold on our capacities for original thought and envisioning societies where the least have what is necessary, and communities and ecosystems thrive.

“So join the new revolution, revolution!

To free the battery human.”[7]

What happens in the classroom among students and teachers, the alchemy of learning, communicating, in a community, fosters hope. This is our hope. The complex challenges these students will be navigating require both a capacity to sit with not–easily–solved challenges as well as the empathic capacity to “experience” from another being’s point of view.

The digital story assignment, when designed thoughtfully, can participate in desiring transparency, strengthening collaborative skills, engaging with complex subject matter, facilitating creativity, and understanding the other.

This hope is foundational to education, revealing the prevailing assumptions that shape societies, providing nurturing classroom situations to foster new ways of thinking, and considering old wisdoms in a new light.

I leave you with student Austin Hermann’s digital story and his reflections on the impact it had on his life.

Together, we are changing the story.

Student Austin Hermann on where digital storytelling can take you

A digital story by Austin Hermann, “Water Wars”

Feedback/Errata