1 Chapter One | What is digital storytelling?

Linda Buturian

Digital storytelling can be a potent learning experience that encompasses much of what society hopes that students will know and be able to perform in the 21st century.Bernard Robin[1]

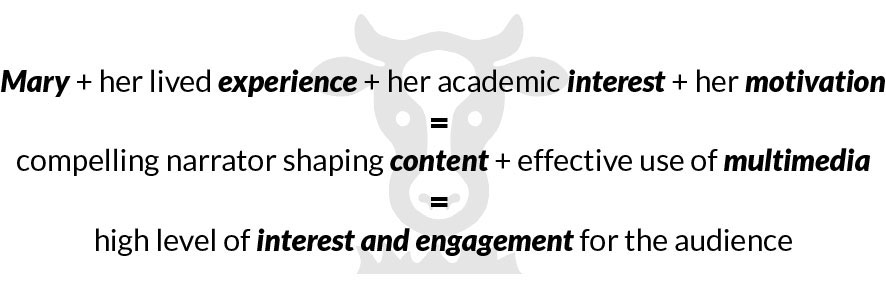

Mary was one of 15 freshmen in my undergraduate seminar “Water, Water, Everywhere? Investigating & Protecting our Life Source.” The water seminar introduced students to water resource topics from the disciplines representing both humanities and the sciences, and required each student to create a digital story. This particular digital story assignment was a culmination or capstone project which was introduced two-thirds of the way into the semester; each student was asked to create a five to seven-minute movie that combined audio, video, and text in order to educate viewers about a water resource topic. Students integrated research and a first person interview that they conducted with a relevant expert in order to communicate their information in a story form. New to digital stories Mary was nervous about creating a digital story as she, like most students, had never made one before.

Was it a kind of research paper with pictures?

A digital story by Mary Zahurones, “Manure Management for Moo-filled Lands”

Mary chose to do her digital story on manure management on dairy farms as it relates to water issues. Mary had a rhetorical challenge on her hands.

We are talking manure.

Poop.

Cow dung.

Cow pies.

Waste.

For most of us, cow manure was about as interesting as dragging a two-by-four around; we’d rather not visualize the 120-or-so pounds a single dairy cow produces in a day, multiplied by what seemed like a gazillion cows in our state.

We were not inclined to be invested in how surprisingly complicated manure was as a research topic, nor its importance in the context of water quality, but Mary was.

Water pollution from manure as well as synthetic fertilizers can lead to serious environmental damage and harm human health.

Mary Zahurones [2]

At this point in the semester, we had learned that Mary’s family had a dairy farm in rural Minnesota, and that she was recently named the 58th Princess Kay of the Milky Way. [3]

As the Dairy Princess, Mary served as a kind of ambassador to the 4,500 dairy farmers of Minnesota. The year-long opportunity involved visiting schools, meeting with farmers, participating in parades throughout the state, and having her likeness carved out of 90 pounds of butter at the Minnesota State Fair (with long lines of ice cream-eating fair goers trooping by her posing in a rotating glass cooler for the butter statue).

Her classmates and I suggested to Mary to connect her research in manure management to her family farm – maybe take photos of her working on the farm, of her family’s cattle, of the barn and tractor. In terms of the narrator, if she was thinking about being in her own digital story she could include footage of herself being crowned Princess Kay and maybe even talk about manure management with some of the dairy farmers she met.

She could bring her star–power to poop!

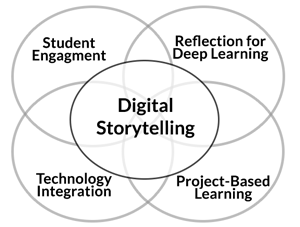

The assignment that Mary and the other water seminar students created is one version of the digital storytelling assignments that educators are using for academic purposes. The term “digital story” has become a catch-all for projects ranging from a two-minute narrated PowerPoint to a 10–minute video documentary. For our purposes, the University of Houston’s educational website sums it up cleanly: “Digital storytelling at its most basic core is the practice of using computer-based tools to tell stories.” [4]

Digital Story In Action

Classrooms as a Mandala is loosely based on my essay, “Everyday Epiphany”and is a different kind of digital story that uses an interactive interface to tell the story of how a classroom can be more than a place for gathering. The participatory nature of our classrooms are a mandala of sorts that brings students and teachers together in moments of knowledge creation. I collaborated with The Changing Story team on Classrooms as a Mandala in order to communicate my epiphany that as educators engaging with our students in a classroom, we create a kind of mandala of knowledge.

Instructions: To interact with the multimedia story, Classrooms as a Mandala, click or touch different sections of the blackboard to experience an example of how a digital story can take on more forms other than a video.

A collaborative digital story “Classrooms as a Mandala”

Accessible Content Classrooms as a Mandala materials

Stories are foundational to learning

My 20 years of teaching the humanities to undergraduates concurs with the research that “Stories help build connections with prior knowledge and improve memory.” [5]

A colleague I met recently, who is an MD, is choosing digital stories as the means by which to present case studies to the 40 residents he oversees to help them work more effectively with children with terminal diseases. As he put it, “I remember the information from medical school because of the stories about the information, not the information itself.”

Stories help build connections with prior knowledge and improve memory.[6]

As a result, good stories are remembered by students.[7]

As Bernard Robin, Associate Professor of Learning, Design, & Technology at the University of Houston explains, “At its core, digital storytelling allows computer users to become creative storytellers through the traditional processes of selecting a topic, conducting some research, writing a script, and developing an interesting story. This material is then combined with various types of multimedia, including computer-based graphics, recorded audio, computer-generated text, video clips, and music so that it can be played on a computer, uploaded on a web site, or burned on a DVD.” [8]

The University of Houston’s Digital Storytelling site has identified the core elements of an educational digital story, ⁸source: The 10 elements of digital

storytelling from Educational Uses of Digital Storytelling (adapting Seven Elements of Digital Storytelling created by the Center for Digital Storytelling). [9]

Scaffolding

In Chapter 3, you’ll find low stakes exercises aimed at assisting students in becoming familiar with each of the following elements of a digital story:

- The Overall Purpose of the Story

- The Narrator’s Point of View

- A Dramatic Question or Questions

- The Choice of Content

- Clarity of Voice

- Pacing of the Narrative

- Use of a Meaningful Audio Soundtrack

- Quality of the Images, Video & other Multimedia Elements

- Economy of the Story Detail

- Good Grammar and Language Usage

“At its most basic level, a digital story is a story told in a digital format that shares a point of view, often the storyteller’s point of view. Digital stories are essentially personal expressions with a purpose. Using personally meaningful visual and aural elements (e.g., personal photos and the storyteller’s own narration), the digital storyteller delivers a relevant ‘lesson learned’ that extends beyond her or his specific experience to human experience in general.” [10]

Why digital stories are relevant in today’s classrooms

Instructors from across the University of Minnesota, as well as from high schools and community colleges, have used digital storytelling in disciplines from introductory cellular biology to graduate courses for international students. My experience integrating digital stories in the water seminar led me to adapt the assignment for courses including a hybrid introductory literature course, a first year inquiry course I was team-teaching with a colleague to 100 freshmen using iPads to create the stories, and a learning abroad course in Northern Thailand.

I teach with digital stories as a part of a course design that aims to transform student learning. “Transform” here means: for each student to experience a deepened understanding of their relationship to the subject matter; to gain more of a sense of agency in their own process of learning; and to view themselves as vital participants in a collective working together toward a shared objective. The digital story assignment can play a powerful role in fostering a depth of learning by the individual student, as well as the community that is created in the classroom, about the course content. When successful, each student will emerge from the course with a transformed understanding of both the course material as well as their perceptions of their ability to make a positive difference in society through the use of their academic skills and their participation in the collective. As Joe Lambert put it, author of Seven Elements of Digital Storytelling, “Each of us is tasked with the challenge of aligning purpose and passion while negotiating personal autonomy and simultaneously strengthening community ties.” [11]

I designed the water seminar to equip students with both knowledge about, and agency in, their ability to navigate the resource challenges they and others will face in their lifetime. The students came into class knowing very little about water and emerged from the course with an introduction into the systems that perpetuate unequal distribution to access to clean water, as well as viewing most every thing they use, eat, and drink as a gift of water – a gift that is inequitably disbursed locally and globally, and a gift that students are active participants in regard to its quality and accessibility.

No one assignment can achieve this kind of transformative effect. The digital story, when thoughtfully designed, scaffolded, and planned into the learning design for the course, can be a powerful element in the dynamic of transformation. When students go through the process of choosing a topic, creating a storyboard of the multimedia elements and content, integrating research, shooting still shots, video, choosing audio, determining their narrative stance in their story, determining how best to communicate their findings in a visual realm, and then revising and editing it from peer feedback – all the while knowing that their story will be viewed by others – the digital story assignment can be a kind of

initiation; a baptism into the fold of knowledge.

Mary was already a strong and excellent student, but her investment in the digital story project helped her become even stronger as her academic work dovetailed with her lived personal experience. Her motivation to do well was also spurred on by knowing that her digital story, along with the other students’ stories would be published on a public college-hosted website where it could be viewed by family, friends, farmers, and more.

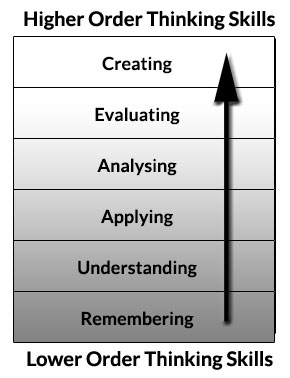

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, from the educational origami blog [12]

While the research on digital storytelling is still emerging, several scholars and researchers help us understand why the process of creating a digital story can be transformative. Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy sheds light on the higher level critical thinking skills involved in creating a meaningful, academically viable, digital story. Students must absorb information as well as understand the medium in order to be able to turn around and communicate their findings effectively as a digital story.

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy, from the educational origami blog [13]

The Strongest Voices

The strongest voices on digital storytelling are those of the students and teachers who have worked with and used them in the classroom. The Changing Story connects you with some of these voices through video interviews.

Student reflection videos are in Chapters 1, 2, 4, and 5. Paired with each reflection is the digital story assignment that the student speaks about in their reflection. The voices of the students coupled with their work extends a powerful “behind the scenes” view of digital storytelling.

Teacher reflection videos are in Chapters 1 – 4. These video interviews offer a wide range of ideas and experiences from teachers in various institutions from high school to higher ed.

Student Work and Reflection

Sara’s digital story went away from the traditional video–based assignment and took the form of a graphic story. Her reflection on how she decided her topic, as well as how it changed her life, is a beautiful telling of how digital storytelling can, and will, impact your students beyond the classroom.

Student Sara Hayat behind the scenes of

“Remembering an Old Friend”

Sara’s digital story took the form of a graphic story.

A digital story by Sara Hayat “Remembering an Old Friend”

Teacher Reflection

The teacher reflection video for Chapter 1 is a general reflection on what digital storytelling is and what it means to teachers. The strongest voices on digital storytelling are those of the students and teachers who have worked with and used them in the classroom. Student reflection videos, placed throughout The Changing Story, matched up with the digital story assignments that the students made and speak about in their reflection videos.

In addition to student reflection, The Changing Story provides you with teacher reflections as well. At the end of each chapter is a video of teachers from high school and higher ed institutions reflecting on their experiences with digital stories. Chapter 1 is a general reflection on what digital storytelling is and what it means to teachers.

Digital Storytelling in the Classroom

- Source: Bernard Robin, Associate Professor, College of Education, University of Houston ↵

- source: The Sustainable Table, an organization that promotes a more sustainable future ↵

- http://www.kare11.com/news/article/935705/207/Pierz-woman-crowned-2011-Princess-Kay-of-the-Milky-Way ↵

- source: University of Houston, College of Education ↵

- source: “Tell Me a Story: Narrative and Intelligence” by Roger C. Schank ↵

- source: “Tell Me a Story: Narrative and Intelligence” by Roger C. Schank ↵

- source: Teachers' pedagogical stories and the shaping of classroom participation “The Dancer” and “Graveyard Shift at the 7-11” by Rex, Murnen, Hobbs, and McEachen ↵

- source: “Digital Storytelling: A Powerful Technology Tool for the 21st Century Classroom” by Bernard Robin ↵

- source: The 7 elements of digital storytelling from StoryCenter.org ↵

- source: From pixel on a screen to real person in your students' lives: Establishing social presence using digital storytelling” by Lowenthal and Dunlap ↵

- source: “Seven Stages: Story and the Human Experience” by Joe Lambert ↵

- source: Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy ↵

- source: The Digital Storytelling Diagram, adapted from California State University Long Beach ↵

Feedback/Errata

1 Responses to Chapter One | What is digital storytelling?