2 Chapter Two | Types of Digital Stories

Linda Buturian

The habits of wonder promoted by storytelling thus define the other person as spacious and deep, with qualitative differences from oneself as well as hidden places worthy of respect. Martha Nussbaum[1]

I trust you are as busy as me and unless you are a tinkerer by nature, you don’t have time or inclination to plunge yourself into the next big tech–thing. Since I began working with the digital storytelling assignment in 2008, I have tried and abandoned several other media–based assignments, apps, and innovations that were recommended to me. Each of these ventures required my time and energy, and often classroom and students’ time as well. As I flailed through these attempts, I found myself returning to the digital story assignment, and over the years and in different courses, I adapted the essential elements of the genre to address diverse topics and learning objectives.

Jason B. Ohler, author most recently of the book, Digital Storytelling in the Classroom, sums up the generative nature of this investment:

Digital storytelling is not only personally empowering but also widely applicable across genres and academic areas. I’ve seen compelling new media pieces produced by students that explicate the works of authors as diverse as Shakespeare and Sylvia Plath. The new media documentary is rapidly becoming a respected and even expected format for student presentation.[2]

Once you have decided that a digital story is the preferred medium for your learning objectives, the next step is to ascertain which type of assignment is most aligned with your goals. I have found that the Backward Design[3]

What should students know, understand, and be able to do?

Backward Design brings to mind the line from T.S. Eliot’s poem Four Quartets, “In my end is my beginning.” Picture your students leaving your classroom at the end of the course. What kind of learning do you want them to carry into their futures? How does your digital story project fit in to the “dream of learning” that you wish for your students? As educators we must start with our expansive dreams for learning because the path inevitably narrows due to time constraints, class size, budgets, and standards. If we don’t begin with our dreams, we find ourselves defaulting to the textbook assignments, capitulating to what is expected. Thanks to Langston Hughes, we know where a “Dream Deferred” leaves us. In Hughes’ opening stanza of “Harlem, ”

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?"Harlem" by Langston Hughes

Sobering, a teacher who has lost her dream, day after day in front of a class full of students...

Let your dream (or vision) for your students inform your learning goal for the assignment, then proceed to what you count as signs, or evidence, that the students have achieved the goal (this will shape assessment), and what you want them to be able to do once they’ve created, shared, and reflected upon the making of the digital story project.

Do you dream about:

- Your students harnessing their academic skills and passion to help make the world a better place?

- Your students being able to reflect on their own path to understanding?

- The lights going on in your students' minds about the meaning of a passage they are struggling to translate from another language?

These dreams inform the three different categories of digital story assignments I gathered for The Changing Story. There are more variations of these versions, and hybrids too, and you may also have good examples of these or a different kind entirely from your own classes.

Three categories of digital stories

The rest of this chapter examines three categories of digital stories: digital stories as a social education tool, digital stories as a reflective assignment, and digital stories that communicate a concept. Each type of story includes a description, an application of the Backward Design model, a reflection on the learning objectives that may be fulfilled, and examples of student digital stories from my own as well as colleagues’ classes.

Digital Stories as a Social Education Tool

Description

In the water seminar, my capstone digital story assignment asks each student to create a 5–7 minute digital story that educates the public about a water resource topic. In essence, it is a problem/solution assignment. The students choose a specific topic to research, then develop a story that integrates their research and features a first person interview with a relevant person (conducted by the student). I chose this capstone digital story assignment to replace a research paper because students could employ images and music to better share their findings, shape their academic work around their distinct personalities, and use their social media networks to disseminate the stories. The digital story assignment allows students a dynamic forum to communicate their keen sense of justice, educate others, name what is unfair in their region, and suggest solutions.

Dream (Backward Design)

The digital story process provides a crucial element in the transformative learning that occurs throughout the seminar, so that students not only learn about water resource issues, but they are baptized, initiated, and bonded (as in the chemical process) to their learning. They experience the deep, enduring kind of learning that alters their lens of perception about the connection between water and most everything they come in contact with in their daily lives, as well as their understanding of global issues. I want them to harness their creativity, passion, and unique personalities to inform their digital stories, and because they are comfortable enough with the technology and the concepts, they create an engaging, academically

strong story they are proud to share with friends, colleagues, families, and the public.

Learning Objectives: What should students know, understand, and be able to do?

Know: Accurate knowledge about the topic which includes understanding the topic from multiple perspectives; how to think through their choices in narrating the story, as well as their vantage point on the topic;

Understand: Proficiency in accurately integrating, and citing research; fair, nuanced understanding of problems and possible solutions; rhetorical situations – the stories are housed in a public website the college supports (example: So what does general public know about pharmaceuticals in their water supply? Rainwater harvesting techniques in India?); the learning that occurred in the process of developing, editing, and sharing their digital stories.

Be able to do: To research one topic in depth, experience interviewing a relevant expert, and to communicate their knowledge effectively by using the elements in this multimedia genre; engage in a dialogue about their water resource topic as well as their process of creating the digital story.

Student Examples:

In an upper division course, “Solving Complex Problems: Mississippi Local, Global Community—: Based Approaches to Living with Rivers, Sustainably”, students conducted research and fieldwork in the community and met guest speakers from the arts, sciences, and local organizations. They watched the digital story my colleague and I created, “Mekong Mosaic” and identified resources about other troubled world rivers, such as the Jordan and Nile. Then each student created a digital story about one aspect of the Mississippi River. The digital story assignment incorporates research, an interview with a relevant person from the community, university, or business, and some combination of video clips, music, voiceovers, and photographs. Along with choosing the topic, the student creates a storyboard, writes the story text, selects the music and the specialist they want to interview, as well as chooses the media elements

they want to use. It is harder than it may appear to research, edit, and produce what is essentially a short film in one semester.

Student Megan Trehey's digital story illustrates life along the upper Mississippi River through the artistic expression of Peter L. Johnson. Johnson uses found material, “waste”, from the Mississippi River to create his body of work. Megan’s reflection video shows how a digital storytelling assignment can help your students to reach beyond what they would normally do for a “traditional” assignment such as a research paper.

Student Megan Trehey behind the scenes of “River Journey”

A digital story by Megan Trehey,“River Journey”

The digital story “Climate Change and the Mississippi River” by Phoebe Ward is an example of what people are doing to address the water–related challenges that are at the heart of many local, regional, and global conflicts.

A digital story by Phoebe Ward,“Climate Change and the Mississippi River”

Several of my colleagues are using digital stories to enrich student's learning. A collection of digital narratives by First Year Students with iPads can be seen at the Student Gallery grouped into topics such as: Community, Hard Work: Immigrant Perception of the American Dream, and Bullying in Schools.

Mitra Emad, associate professor of cultural studies & coordinator of Cultural Studies program, University of Minnesota–Duluth, incorporates digital stories that disrupt our preconceived understanding of knowledge. She teaches and writes about cultural constructions of the human body, especially in terms of how the body functions as a site for cultural translation.

Her student, Garrett Soper's Capstone Project “Eyes”, is a personal story about his relationship with food, specifically living animals that he has caught and killed.

A digital story by Garrett Soper, “Eyes”

Ariana Koras, who also took Emad's Cultural Studies Senior Seminar, uses digital storytelling to discuss the Social Charter being developed for the Great Lakes region to establish the waters as common property that belongs to the people and protect them for generations to come.

A digital story by Ariana Koras, “A Superior Ambition: The Great Lakes Social Charter”

Digital Stories as a Reflective Assignment

Description

In this assignment, the emphasis is on students reflecting on their process of learning. The Center for Digital Storytelling. [4]

(CDS) is the resource I most identify with this type of digital story, one that is informed by first person narration. The digital story as a reflective assignment seems to lend itself to this metacognitive process, especially with the increasing access to mobile devices: because students have the tools in their hands.

Dream (Backward Design)

Students make the critical shift from unconscious to conscious learning. Through the digital storytelling process, I provide a space for them to reflect on their own journey toward knowledge. To use their voice to reflect on their learning, and choose examples from their knowledge to help viewers connect with how they learned what they learned. In this way, the act of creating the digital story participates in the students’ self awareness of their learning.

Learning Objective: What should students know, understand, and be able to do?

- Know: Students should know their own learning process; know how to utilize the media elements to communicate their path toward knowing.

- Understand: How their learning process fits in the larger construct of the subject matter they are reflecting on.

- Be able to do: articulate their learning effectively, both in their digital story as well as in person, to peers in the class, and to the general public.

Student Examples

The following is an example from my course, Creating Identities through Art and Performance, in which students create and explore art in different mediums. Students examine concepts such as place, self, and identity. Caitlin Dillon's video “My Shoes Tell a Story” is about her life with running shoes and the journey they've taken her on.

A digital story by Caitlin Dillon, “My Shoes Tell a Story”

A final example of a reflective digital story assignment rises out of the University of Minnesota President's Emerging Scholars Program (UMNPrezScholars) which is a four–year opportunity for undergraduate students. Students receive professional advising, peer mentoring, and opportunities for engagement to ensure a positive and successful University of Minnesota experience. Steve Cisneros, director of the program, has worked with students to create a digital story that combines effective writing with digital media technology . He uses the digital story as a tool for students to identify personal, academic, and career goals and how the University will help them meet those goals.

Digital Stories that Communicate a Concept

Description

In this type of digital story, students create digital stories that communicate their understanding of a relevant concept. Whether it is demonstrating a biological principle, translating a passage in French, or educating the viewer about the benefits of a particular turf grass for a good lawn, the creative possibilities for doing so are endless.

Dream (Backward Design)

Each student (or group of students) will read, absorb, and integrate the subject matter in such a way that they will be inspired to produce a multimedia story that communicates their understanding of the topic in a creative, engaging way shaped by their distinct personalities. This type of digital story will reveal that students understand the topic in context to the larger, dynamic field of knowledge, as well the significance of the topic to the general public.

Learning Objective: What should students know, understand, and be able to do?

- Know: the research analysis of the relevant field; integrating scholarly info effectively as part of the digital story; the connection between specific concept and larger field

- Understand: the specific concept, and how it relates in the dynamic nature of the topic; media literacy; rhetorical situations.

- Be able to do: give and receive feedback on digital story draft and edit story to strengthen and refine; communicate with peers and general public, both in the multimedia genre and in person; video production; engage viewers creatively; be able to respond thoughtfully to the question of why this matters.

Student Examples

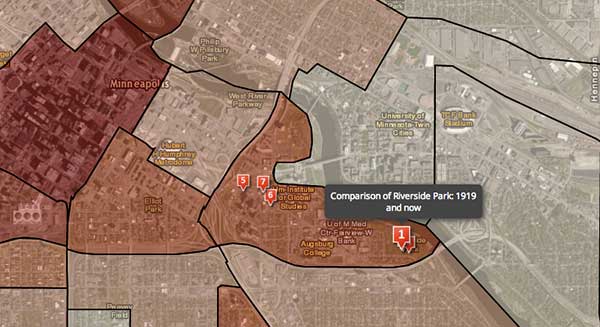

Spatial mapping and digital stories came together in a project co–designed by Assistant Professor Eric Castle (U of M Crookston) and Associate Professor Akosua Addo (U of M School of Music). Addo’s “Mapping Arts Play” class and Castle’s “GIS Applications” class worked together to design interactive maps that told a digital story about the diverse, immigrant Cedar–Riverside neighborhood near the U of M Twin Cities campus. The dynamic maps facilitated student collaboration while creating an enhanced digital story using the knowledge and expertise of each class.

A digital story by Maria and Bailey, “Comparison of Riverside Park: 1919 then and now”

A digital story by Morgan and Joshua, “Cultural Play in Curry Park”

Digital Stories for Teaching

Digital storytelling as a teaching tool is an emerging genre in academic learning. Recently my colleague Catherine Solheim, associate professor of family social science at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, and I created a digital story about our travels to northern Thailand to interview villagers along the Mekong River about the impact of climate change and globalization on their culture and ways of living. We are using it in our respective classes (in different departments) and in our learning abroad course in northern Thailand. I shot most of the interviews and photographs while in Thailand, as Cathy was busy translating and conducting the interviews. We were fortunate to receive support from the college through the help of a videographer to edit and produce the story.

A digital story by Linda Buturian and Catherine Solheim “Mekong Mosaic”

The benefits of the digital story as a teaching tool: we are practicing what we ask of our students and discovering the challenges and benefits they most likely encounter. Students like learning from brief engaging videos,and respect the fact that the teacher is doing what is asked of them. We have a teaching resource we can return to.

The challenge: its hard to make a good digital story, and takes a lot of time to shoot, write a storyboard and script, and either find technical support or time to edit and produce a quality story. Mitra Emad, associate professor of cultural studies & coordinator of Cultural Studies program at the University of Minnesota Duluth created the story “Going Digital”

[5] and uses it to teach a unit on debunking digital natives. She has also used it to teach storyboarding in the process of making digital stories. Emad created a story alongside her students in Critical Animal Studies: “Cages”[6]which didn't end up being much about animals, and serves as a relevant lesson for helping students.

Faculty members have produced video abstracts for their research that are similar to student produced digital stories, which can be used in teaching as well. For example, Marla Spivak produced a video abstract[7] for a co–authored article in Environment Science and Technology.[8]

“Don’t ask your students to do anything you haven’t done yourself” – one of the teaching credos—has been troubled by the presence of rapidly changing technology in the classroom. Back in 2008, the first few semesters I assigned digital stories, I had not gone through the process of making one myself, and that was troubling for me on pedagogical grounds as well as pragmatic matters of really understanding what students were navigating. When the time is right and the opportunity arises, consider creating your own digital story. It may or may not serve as a teaching tool in your classroom, but it will teach you.

In the Backward Design model, once you have determined which digital story assignment would best meet your learning objectives, you move to determining an assessment that reflects your learning objectives, and then focus on low–stake assignments (scaffolding exercises) that isolate the techniques and elements necessary to create a digital story assignment.

Teacher Reflection

The teacher reflection video for Chapter 2 focuses on the types of digital stories teachers have used in their classes as well as why they chose those types of assignments. Notice the variety in type and style of story and how it influenced their students.

Digital Storytelling Assignments

- source: Coulter, D. L., Weins, J. R., & Fenstermacher, G. D. (2009). Why Do We Educate: Renewing the Conversation (pp. 148). New York, NY: Wiley & Sons. ↵

- source: Ohler, J. B. (2013). Digital Storytelling in the Classroom (ch. 3). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. ↵

- source: The Backward Design Model is helpful in determining the particular tenets and scope of a digital story assignment. Wiggins and McTigh state that, “One starts with the end – the desired results (goals or standards) – and then derives the curriculum from the evidence of learning (performances) called for by the standard and the teaching needed to equip students to perform.”[footnote]source: Understanding by Design Method, Wiggins and McTigh, 2000, page 8 ↵

- source: Storycenter.org ↵

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8DefqM6Jhc ↵

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1_uwvKch6o ↵

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=31XsEAGveFA ↵

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/es101468w ↵

Feedback/Errata