1.7 Project Management Example

Mark Twain once began a letter to a friend with these words: “Forgive me, if I had had more time, I would have written a shorter letter.” It is not difficult to explain a big project, but it takes a lot of time and effort to be clear and concise. Below is an example of a “one-sheet” created to explain the first Peavey Plaza redesign to key stakeholders and potential funders and donors. There was also a longer (ten slides) slide show but this captures the whole project on one page.

Time

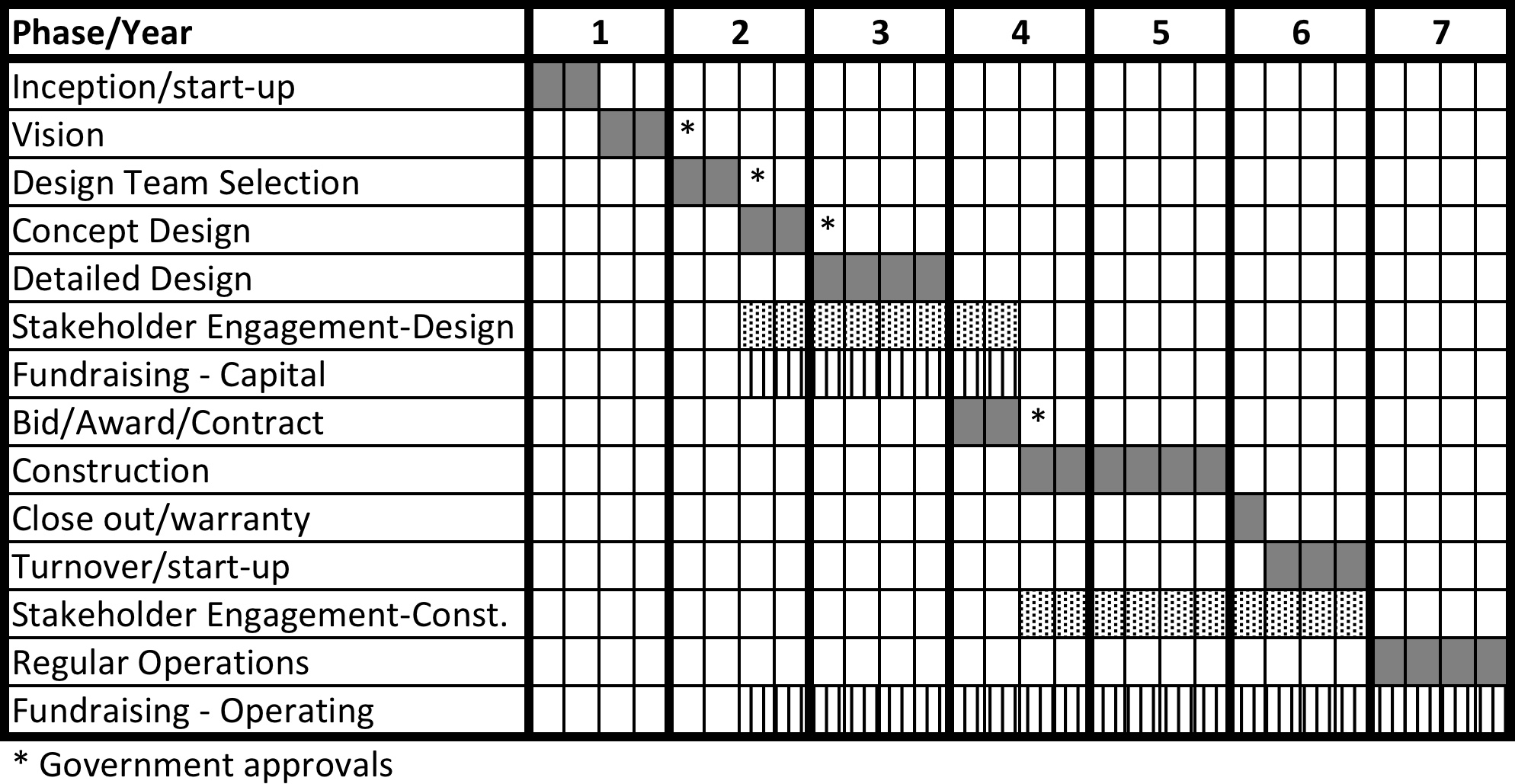

Once you have considered the WWWWWH of a project and figured out the purpose, scope, schedule, and budget, the next thing you must do is to apply your answers and plans to a timeline and start thinking about how the project might unfold. In many ways this is like writing a play, and for the typical project, I propose there are eight acts to this play: Inception/start-up, Design Team Selection, Stakeholder Engagement, Concept Design, Detailed Design, Fundraising, Construction, and Normal Operations. This is what these acts or phases look like when applied to a conceptual bar-chart type of schedule:

This schedule could apply to any reasonably sized project and while seven years seems like a very long time, when you think of everything involved, time passes quickly. In this case, the public would begin to notice the project in year three and begin using it in year six, so it is really a three-year project, but the start-up could take a year or two and the switch over to regular operations and fine-tuning of the facility and the operations could take another couple of years after construction has been completed. Below is a more detailed description of each phase:

Phases

Inception and start-up:

This is when a project promoter assembles a group of key actors to propose a project. It may be a single meeting or it could be the creation of a working group that meets regularly for a few months or a year or two to convene the key stakeholders, come to agreement on the need and principles, and draft the framework for how the project might be implemented. This could be led by city elected officials and staff or a combination of city, private, non-profit, or other interested parties getting together and agreeing that a project is worth trying to implement. The original vision can come from a small group of businesspeople or community members or it can be a single person like the mayor, a business leader, a philanthropist, a property owner, or a developer.

Vision:

The next step is to create a governing group that will shape the vision and help lead the project forward. This might be a small group of city staff and elected officials or it may include representatives of the business community, potential donors, nearby property owners, and other key stakeholders. This group may form a “steering committee,” an “advisory committee” (advising city staff but not deciding), or an “implementation committee” (with a greater role in decision making). There may also be a fundraising committee made up of private individuals and representatives of businesses who will help fund the project and therefore will also have a say in design and implementation. This group will develop a vision and principles for the potential project. This group may also approve and promote a very conceptual schedule and budget developed by staff. The same group may also take steps to secure support of the city government for the project, either unofficially or more officially if, for example, some funding must be appropriated or if it is necessary to acquire property.

Design Team Selection:

Assuming a funding source of some kind (the city, state, or maybe a donor), the leadership group and staff will structure a designer selection process. This may be a design competition or, more typically, a process that begins with a “Request for Qualifications” (“RFQ”) followed by a “Request for Proposals” (“RFP”) (sometimes there is no RFQ). Since most public realm projects have some kind of public participation and public funding, the design team and contractor selection process is likely to be run as public procurement process through the city’s purchasing department and the process must be transparent and competitive. Usually, you cannot just decide to hire someone you like.

The group leading the project will use their vision and principles as the basis for the RFQ/RFP. The RFQ/RFP should give the potential designers enough background and direction so that they understand the project, including history, objectives, conceptual budget, and schedule constraints. They will submit a proposal that describes their understanding of the project, their approach to the work, and their key team members. They will also include examples of similar relevant projects, resumes, and a fee proposal. The leadership group will play a role, along with city staff and perhaps other stakeholders, in reviewing the proposals, creating a shortlist of finalists, participating in interviews with the finalists, and recommending a winning design firm or team. (More on this process in Chapter 2.)

Concept Design/Stakeholder Engagement:

Once the Design team has been hired, they will analyze the site, meet with and interview a variety of key stakeholders, host public meetings, open houses, and other events, and use online surveys and social media to seek input, all with the purpose of validating the vision and creating a “program” for the place. The program describes both the quantitative needs of the place describes not just the physical size and characteristics of the place (for example, two soccer fields of regulation size and a 200 square foot, one-story public restroom building that includes storage for maintenance equipment) but also the anticipated use and experience of the place (for example, a public plaza with specific power and lighting infrastructure in support of intensive use for organized programs and activation use vs. a park with grass, shade trees, and benches for relaxation). More important than the physical and quantitative needs of the place is a clear understanding of the intended use and experience of the place.

They will then create a series of preliminary design drawings – site analyses and bubble diagrams to begin with – for review and discussion with these groups and stakeholders. Using an iterative process, the designers will add detail to their drawings and integrate the feedback they receive from all of the stakeholders into a single “concept design” that is based on the vision and principles, input from their initial meetings with the group steering the project, and community engagement process including public meetings, surveys, and other information gathering processes. The objective is to combine site analyses, user needs, and stakeholder perspectives together into a concept that satisfies the original objectives and the key stakeholders and that fits a budget. The concept design will include a cost estimate that the team will use to establish a more detailed budget – and to determine the amount of funds that must be raised.

Is Designing for Active Programming Good?

In recent years, there has been a move in park production to design and build to maximize organized programming, events, and activation. For example, a park may be designed to support 80 revenue generating programs a year, small, medium, and large, including music events, arts fairs and so on. A part of this movement is based on the idea that programming revenue will significantly offset operating costs and perhaps even make the park revenue self-sustaining but in practice this rarely works out and more often the revenue does not meet initial projections. At the same time, the operating costs go up with the event usage, as events require more security personnel, power, the trash pick-up, as well as the costs of wear and tear and maintenance, for example the replacement of damage grass after a concert.

But more important, when the emphasis is on programming, the idea of a just relaxing in an un-programmed park may get lost. Landscape Architect Mary Margaret Jones has become concerned with the growing emphasis on active programming, concluding that, “too often, people ask ‘what do you want to do in the park’ when the real question should be ‘how do you want to feel in the park?’” The first question pre-disposes people towards thinking about “activities” when the second gets at just enjoying being in a park.[1]

Fundraising:

At the very beginning, the project leadership must develop a strategy for raising the public and private funds required to pay for the project and the concept design will become the primary tool used for that fundraising effort. The concept design will include renderings that help people understand what the project will look like. Potential funders – both government officials and potential donors – will have opinions and feedback on the design and these will be incorporated into the design and renderings, if feasible and reasonable, to cement their support.

Fundraising has two components: “Capital Funds” and the “Operating Reserve.” The first priority will be to raise enough funds to design and build the project. Some funders will only promise funds with the stipulation that other funds are raised and promised before they will write the check. For example, the state of Minnesota often makes grants to these types of projects however it requires a complete and detailed capital and operating budgets (and a lot of other information), as well as proof that all other funds have been secured, before it will distribute any funds to the project. The state’s funding is the “last-in” dollars. More generally, with a public project, you cannot start with half the funds – you have to have all of the funds secured before you sign a construction contract.

Therefore, cash flow is important because in addition to last-in grants, like those form the state, some donors may elect to give timed gifts. For example, a donor may give $500,000, in annual installments of $100,000 per year, every year, for five years. But if you need all of the money in year one to get started and plan to complete construction in year two, this isn’t really a helpful gift – not that you don’t want the money. In this case, a different party (for example the city) may make a “bridge loan” by loaning the project the full amount of the grant (or 4/5ths of it) in the first year and then collecting the proceeds to repay itself over five years. The loan is secured by the pledge or promise of the donor to make the future donations. The reasons a donor – whether it be a private individual, a corporation, or a foundation – would choose to make a timed gift with a specified payment schedule may include estate planning purposes, taxes, future income or cash flows, or other business or personal reasons.

Detailed Design:

Once the concept design has been completed and has secured general support from city elected officials, stakeholders, and funders, the design team must continue with detailed design. Concept design may take six months and go from blank sheets of paper to renderings of a place. Detailed design can take much longer – another six our twelve months, but this phase is more about refining the ideas and the details. This might include deciding what type of plants, benches, and light poles to use and where or how to detail the paving – concrete, pavers, or other. Detailed design bring the project from soft focus into clear focus – from big ideas to detailed refinement. The detailed design won’t look very different from the concept design but it will result in more information – enough to solicit bids from contractors. The product of the completed detailed design phase is a big set of drawings and a specification book – a thick book filled with detailed information describing every product and system from how to compact the dirt and the exact ingredients of the concrete mix to exactly how many outlets of which type will be purchased and at what height they will be mounted on the light poles. The drawings and specifications (“specs”) together are called the “construction documents.”

The design team will also prepare a more detailed cost estimate based on these documents to determine if the project is still within budget and help prepare for analysis of the bids. The estimate may be over or under the previous estimate (usually over) and when that happens, the project team may choose to change or delete certain features through a process known as “value engineering” to reduce costs; or to bid certain features as discrete “alternates” – kind of like making something an extra or upgrade for a specific price, in the same way the fancy wheels, rust-proofing, or navigation system in a car is sold as an extra above the base price. In the case of public realm, “add alternates” (increases to the price for specific changes) may include larger trees, paving stones rather than poured-in-place concrete for sidewalks, and a water feature that can be deferred if not enough funds can be raised.

Bid/Award/Contract/Construction:

The city will issue an invitation to bidders. The bid documents will include the construction documents (drawings and specs) as well as the invitation to bid, instructions to bidders, schedule requirements if any, and requirements for SUBP (small underutilized business participation) targets. This is the expected minimum percentage of the contract value that will go to minority-owned and women-owned businesses and the expected minimum amount of labor that will go to women and minority laborers.

Interested contractors will acquire the bid documents and will take the set apart and bid out pieces of it to a number of subcontractors such as demolition, earthwork, concrete, steel, plumbing, electrical, lighting, and so forth. These subcontractors will each review their parts of the documents, determine the cost of doing the work (labor and materials) and submit a bid for that scope of work. The General Contractor (“GC”) will select the lowest qualified bid from each set of bidding subcontractors and assemble them all into one bid (adding up all of the subcontractors’ bids) for the entire project.

The City will receive bids at a certain location by a certain date and time and will open them in the “bid room” at a published time. A bid opening is open public so anyone can attend and listen as the envelopes are opened and each bid is read out loud – contractor name, total bid/price, and the prices of any alternates. In public bidding the lowest qualified bidder wins. The lowest qualified bid will include a price as well as participation numbers that the contractor must honor. The procurement department will review the detailed information submitted with each bid to make sure it is qualified. For example, the GC must include with their bid proof of insurance, a series of bonds, and anticipated percent and dollar amounts of contracts or subcontracts that will go to minority and woman-owned firms and jobs that will go to women and minority workers. Once the bid has been approved by procurement, the City Council will vote to authorize staff to negotiate with and execute a contract with the lowest qualified bidder.

Once all parties have executed the contract, the contractor will “mobilize” and begin construction. Construction may begin with the setting up of a temporary construction fence surrounding the site, a project trailer and a truck or shipping container full of tools and material. The first work will include demolition, tree and shrub removal, and excavation/earthwork, depending upon the type of project. Subsurface systems will be installed (electrical, plumbing, water, sanitary sewer, storm sewer or stormwater management system, and irrigation) and then construction will proceed vertically.

The contract typically stipulates a completion date – called “substantial completion.” At this point the project is 95% complete or so and ready to be turned back over to the owner/operator and opened to users. The understanding is that contractor still has work to complete but to the average person it should look complete. At this stage the contractor is also required to turn over to the owner an “owner’s manual” – typically a large book of information and instructions on how to take care of, use, repair, replace, and clean all the systems and materials in the new project. This may include information about how to maintain pumps and how often to change their filters, for example.

The contractor must also turnover a set of “as-built” or “record” drawings. During the course of construction many things change, small and large, and the contractor constantly marks up these changes on a set of drawings (paper or digital). So, if an underground pipe is relocated during construction because it can’t go where it is shown on the drawing (maybe there is a boulder in the way that would be costly to move), then the final location of the relocated pipe is shown on the as-built drawings. In the end all of these changes are integrated into one “conformed” set of drawings so that the owner has a record of exactly what was actually built and where.

Close-out/Warranty Work/Turnover:

Between “substantial completion” and 100% completion the contractor completes what is called the “punch list” – a list of items agreed upon between the owner, the designer, and the contractor that are remaining to be corrected or completed prior to the 100% completion of the project and the final payment to the contractor. A one-year warranty begins at substantial completion so during the closeout period and up to the one-year anniversary of substantial completion, the contractor will also be completing warranty work – fixing things that have not held up such as cracked concrete and dead plants and trees. During the closeout period the contractor will largely disappear from the site, and the operator of the new project will take over operations. This can be city or park staff or a non-profit operator.

Normal Operations:

Once the contractor’s work is complete and they are gone from the site, the operator will take over responsibilities for day-to-day operations, maintenance, and programming. Duties including cleanup, maintenance, repair, augmented security, programming, and so on. The operator may be the City in the case of a street; it may be a special improvement district such as the Minneapolis Downtown Improvement District, which provides augmented clean, green, and safe programs in a specific areas downtown that pays a special assessment (a special assessment district); or it may be a non-profit or for-profit operator that subcontracts with a variety of vendors to provide the services. Services include things such as trash pick-up, snow removal, sprinkler maintenance, care and watering of trees and plants, enhanced safety and cleanup through the use of “ambassadors,” and programming such as musical events, block parties, farmers markets, and other forms of activation. The operator will spend the first year or two fine-tuning operations – figuring out how everything works, how to take care of the place, and how to maximize use, activation, and in some cases event revenue required to offset costs of programming. During this period the operator will also be fine-tuning their operating, maintenance, and programming budget to reflect real conditions and costs.

Repeat:

And in twenty or thirty or forty years, when the place is physically worn out, stylistically dated, and no longer capable of meeting changed user needs, the whole process will start all over again.

Conclusion

In future chapters we will learn more about Design, Finance, and Politics. We will end this chapter with examples of different types of schedules and timelines, and a little more information on how projects happen over time, from the moment when they are a just a glimmer in someone’s eye to the day when they are completed and people begin to experience a new public place.

- Mary Margaret Jones, interview with the author, 3 November 2016. ↵