2.2 Project Leadership

The first question is who will be providing the project leadership and guidance at a policy level. This is likely to be the person or people who have initiated the project and it may be a single individual – an elected official, a business leader, or a leader in the community – or it may be a group of people who come together to promote a project. For some projects it may start as a working group or a committee and then become formalized as the group that will establish the vision, provide high-level guidance throughout the duration of the project, and help raise the funds for the project. For other projects the leadership may come from the Mayor’s office or the district councilmember. Yet other projects may originate with senior staff in the City – for example in the public works or planning and economic development departments.

In practical terms, the project leadership group meets periodically (monthly, quarterly, or as needed) and the day-to-day work of the project is planned and executed by the project team. The project team will work together with the chair of the committee and other key team and committee members to plan the leadership group’s work, draft the agendas, and help facilitate the meetings. The following are recent examples of project leadership groups in Minneapolis:

Peavey Plaza:

The Peavey Plaza project is a “public-private partnership” led by a seven-member “Steering Committee” comprised of elected officials and business leaders. The city staff running the project and their hired design team report to and update the Steering Committee on a periodic basis or as needed and involve them in all major decisions including design issues that bear on public’s perception of the project, the interests of nearby neighbors, fundraising efforts, and donor interests.

Nicollet Mall:

The Nicollet Mall project is also a public-private partnership led by the “Nicollet Mall Implementation Committee” or “NMIC.” This group originally started meeting in 2012 as the “Nicollet Mall Working Group,” when business leaders began lobbying elected officials to get the project started. The original idea was that the $50M project would be funded 50/50 with $25M in public funds (state and local) and $25M in private funds (property owner assessments).

The NMIC began with nine members: Five elected officials (a majority) and four business leaders, and was chaired by a City official because, despite the 50/50 funding agreement, Nicollet mall would remain a City-owned street. After several years the “NMIC” committee grew to ten (five and five) and leadership shifted to a representative of the business community as chair for the last several years.

The committee met monthly for the first several years and then less frequently (typically quarterly) as the project was in construction. Members of this committee worked together on everything from lobbying the state legislature for grant funding at the beginning of the project to reviewing design options throughout and then helping to assuage the concerns of the many property and business owners who were affected during construction. Often the public and private representatives played roles that their counterparts could not play.

Together, this group helped select the final design team and review and approve the concept design, detailed design, and many details such as street light fixtures and brand design. Later, this group collaborated through a long and sometimes stressful construction period when all members of the committee received pressure from people who they knew personally and who were affected by the project, from the businesses to the media to people who were inconvenienced during their morning and evening commutes.

US Bank Stadium:

In 2012, The Minnesota State Legislature passed what was called the “Minnesota Vikings Stadium Act,” commonly known as the “stadium legislation,” which created a new Minnesota Sports Facilities Authority and defined the capital and operating funding sources and amounts for the project. The act also prescribed a unique design and review process, which included a requirement that the City of Minneapolis create a “Stadium Implementation Committee” through the appointment of a combination of public officials and private citizens. The purpose of what became a 27-member committee was to review and approve the final schematic design in lieu of the City’s typical development review processes.

The committee met monthly for a year and in order to remain on schedule, their review and approval of the schematic design was required by the end of the summer of 2013. However, in a unique twist of legislative drafting, the stadium legislation left no time for schedule hiccups or redesign – it had to be approved by the end of August, 2013. For example, if the committee were to reject the schematic design and ask for a redesign that would take four months, the overall schedule and funding did not allow for it and the project would collapse. So, the City staff, the Committee, and the design team had to do everything possible to use those monthly meetings to build support for the design along the way to avoid a “no” vote at the end of schematic design. City planning and regulatory affairs staff, too, were closely involved in reviewing the project throughout the entire process to minimize the chances of missing a code issue that would cause a schedule impact. Once the implementation committee approved the schematic design, their work was done and the committee was disbanded, although some members were then appointed to the implementation committee for the “Downtown East Commons” park, which was adjacent to and physically and financially connected to the stadium.

The Commons:

The project originally dubbed “The Yard,” then the “Downtown East Commons,” and now just the “Commons” was led by The Commons Steering Committee, which was made up of some of the former members of the Stadium Implementation Committee (but fewer members – around a dozen) and included city officials, members of the design community, and members of the business community. The steering committee’s role was to develop a vision for the Commons, select the design team, and raise funds for the project. Once the vision had been established, some members of the committee carried forward as the “Fundraising Committee.” The Commons project was part of the redevelopment of a larger, multi-block district that was funded with a combination of city and state funding for the stadium and private funding for surrounding private sector development projects including the Wells Fargo towers, Radisson Red hotel, Millwright Office Building, Edition apartments, and Mills Fleet Farms Ramp. The Commons was initially funded as a part of this overall project but only at a ~$2M “base” level – black dirt and grass seed – a scheme called “the green carpet” that all agreed was inadequate.

So, a big role for this committee, once the project was designed, was raising the additional funds required to implement the full vision. The total project was to cost $22M but only $14M was raised, requiring the deferral of several key features including the concession pavilion, the water feature, and a building designed to house public toilets and park offices and storage. These features may be built in the future when additional funds have been raised.

Hennepin Avenue:

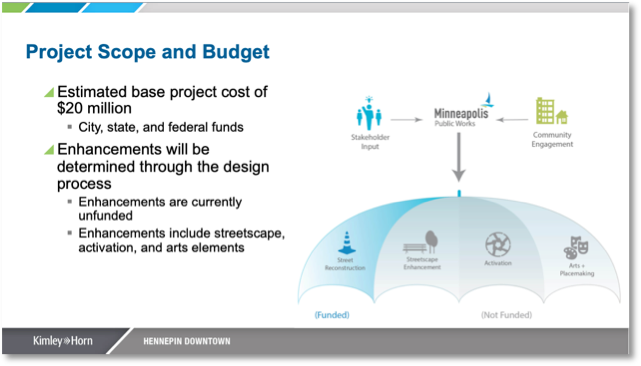

A Minneapolis Public Works department project team led the Hennepin Avenue Downtown Project, with input from a “Stakeholder Advisory Committee” of five members, each representing five major stakeholder groups: The transit company and its transit users; arts and culture, with an emphasis on the performing arts; the downtown business community; the real estate community and, specifically, the property owners on Hennepin; and the downtown neighborhood association.

This project began as standard City Capital Project (see chapter 3) for a “base” street reconstruction project to be a fully funded with local, state, and federal dollars (so this was not intended to be a public-private partnership, like Nicollet Mall). One typical share of the local funds for a street reconstruction project comes from a standard roadway assessment added to the tax bills of the owners of the properties that front on the street. The idea is that the properties benefit from the reinvestment and therefore they should pay to receive that that benefit. The assessment amount can be paid at once or over time in installments that correspond with the term of the bonds for the project (see chapter 3) However, because Hennepin Avenue is also the home of the City’s historic theater district, including three theaters owned by the non-profit Hennepin Theater Trust, there was early interest from some stakeholders in the option of an additional special assessment (above the standard roadway assessment) to pay for enhancements above the base design, such as custom and programmable lighting, more and bigger trees, planter beds, custom concrete sidewalks, and more benches and street furniture.

While these stakeholders were originally meant to play an advisory role rather than directly decide on planning, design, and spending matters, in practice, the stakeholders played just as important a role as the other groups described above. As of the summer of 2019, the project budget was approximately $35M, which included a $31 base project (standard roadway) and an additional $4M in enhancements. The 55 property owners along the street were asked to reply to an advisory petition with a non-binding “yes” or “no” answer to the question of whether they were willing to pay the additional assessment required to fund the enhancements. The results of the petition and a public hearing will influence City Council’s decision fall 2019 as to whether or not they support the enhancements package. Over time, the combination of stakeholder interest in creating more of an arts and culture district through enhanced public realm design caused the project to shift from a city-led, base street reconstruction project to more of a public-private model, but more along the lines of 85/15 public/private split as compared to the 50/50 Nicollet Mall project.