3.4 How do Capital Project Budgets Get Established?

One of the most interesting aspects of capital project work is establishing the budget. Often, people think a great amount of research and study goes into “benefit/cost analyses,” design studies, and construction cost estimates, all as a way to predict what a project will cost. Typically, it is not that complicated.

There are two basic ways to estimate costs. The first way is to hire a design firm and other consultants to complete a study or pre-design or conceptual design that includes a conceptual budget. Then you use that study and those estimates to secure support for the project. The second way is to identify a similar recent project, scale its cost to the new project, and adjust that cost upward to account for inflation. The Consumer Price Index or “CPI,” which tracks annual inflation in the US, was 2.2% in 2019 and it has averaged between 1% and 3% per year since 2000. [1]

For example, if you are doing a project that is similar to one completed five years ago for $12.0M but your project is only 80% the size of the previous project, you would take 80% of $12.0M to get $10.0M. Then you would add on an inflation factor, for example, 3% per year through the completion of your new project. So, if that $10M project were to take five years to complete (plus five years of inflation since the last project was completed) then, assuming ten years of inflation at 3%, the new project would cost a total of about $13.5 in today’s dollars. When possible, it is best to do both a design study with a cost estimate and have some comparable data from a similar, recent project. Then you can compare and reconcile both of those conceptual numbers to arrive at a more refined estimate.

But “how much will it cost?” is not the only question. A second, equally important question is, “how much can we raise?” You have to be able to identify in a rough way all of the realistic potential sources of funds and estimate the amounts you may be able to secure from those funders. This is part cold-eyed analysis, and part gut instinct. For example, “how much did the state give to that other park two years ago and can we get a similar share for this project?” Or “how much will City Council be willing to spend on this project in this ward considering how much we spent on that other project there last year?” Or “is there a private company or individual with a specific interest in this project who may be able to write a big check?” If you cannot figure out where the funds will come from at least generally, then the costs are not really important because you probably don’t have a live project.

For right or for wrong, project budgets often get established before a lot of detailed analysis has happened. This is because you have to take a swing at something before you have even had a chance to hire consultants. More important, when establishing a project budget, it is good to keep in mind the behavioral economics concept of “anchoring” – which is when you fix on something and then have a hard time moving off of it later when there is more information. This means that, whether or not the number had any basis in reality, if you convinced everyone to start a project by telling them it would cost $15 million, then everyone is going to remember that number and it is going to be very difficult to change it later without getting a lot of angry reactions and media responses, unless there is a reason for the change that is good or justifiable, such as the addition of a desired feature.

Which is why it is good to pad your number a bit, if you can, because it is going to take longer than you think and there will be some costs you probably haven’t accounted for. A related way to think of it is that if the cost estimate is $12,455,009, you may want to round up to a higher, easier to remember number. If you don’t, others will anyhow, so you may as well decide that number early. And one benefit of a big, round number is that, as things change, if you have to revise your estimate, that number looks preliminary and conceptual. So $15M sounds pretty good to start, and if you add a feature you may be able to justify later why the number has risen to $16.2M. On the other hand, if the initial budget number is too high, the project will not gain any traction – in this case $20M may just not fly with the project leaders and potential donors – because it does not pass the “how much can we raise?” question.

That is the balance: Your best estimate of a real number (with a little contingency in it) that civic and government leaders can remember and accept – and can imagine raising. The answer to the question “how much will it cost?,” is the best estimate of how much it will cost balanced with gut feeling of the highest possible amount the project leaders can imagine raising, or “how much can we raise?”.

If you cannot answer both of these questions – and the numbers should be close to one another – then you do not have a viable project.

Sources and Uses of Funds

For any major capital project, the first step in creating a budget is to make what is called a “sources and uses of funds” table. This table is simple: First, it lists and summarizes the uses of funds – the costs, or what you will spend the money on. Second, it lists and summarizes the sources of funds – the money you will use to pay those costs. Third, it identifies a “gap” if any, between the sources and the uses. Sources must exceed or equal uses, or you do not have enough money to do your project. Let’s begin with project costs or “uses of funds.”

Uses of Funds

The costs of a capital project include three broad categories: Land, construction, and fees and soft costs. Land might include the cost of purchasing the land, costs associated with survey and platting, geotechnical investigations, environmental testing, environmental cleanup, and soil correction. Construction includes all of the materials and labor required to build the project as well as related costs such as temporary power and water, sewer connection charges, permitting fees, or even the costs of temporarily closing traffic lanes and hooding and buying out parking meters during the construction period (fees paid to the city). Fees and Soft Costs includes fees for professional services such as architectural, landscape architectural, and engineering design, as well as project management, construction management, legal, brand and creative (logo, website), communications, and a host of other professional services. Together, these costs are the Total Project Costs, also known as the “Uses of Funds.” The following is a list of typical project costs:

Land

- Acquisition price

- Soils/geotechnical study

- Survey

- Platting/recording

- Environmental studies (for example, Phase I/Phase II Environmental Site

- Assessments, Environmental Assessment Worksheet or “EAW,” Environmental

- Impact Statement or “EIS,” and Alternative Urban Areawide Review or “AUAR”)

- Environmental cleanup

- Soil corrections

Construction

- Construction contract amount (The cost of labor, materials, bonds, and “general conditions” of the work such as temporary heat, water, sewer, permits, and fees)

- Construction contingency (An additional percentage of the construction contract, 5%-15% for example, to cover the costs of unknowns)

- Independent Testing and Inspections (a third-party laboratory that tests the quality and strength of concrete, steel and other project materials)

- Fixed furnishings and equipment

- Loose furnishings, signage, miscellaneous

Fees and Soft Costs

- Design fees (Architecture, Engineering, Landscape Architecture, etc.)

- Owner’s Representative and/or Construction Management (CM) fees

- Legal fees

- Financing costs including interest on principal of the construction loan, bridge loan, or mortgage

- Staff time dedicated to the project (salaries, benefits, etc.)

- Costs of leasing temporary space (in the case of a temporary relocation)

- Brokerage/RE fees (in the case of property acquisition/disposal related to the project)

- Marketing and promotions costs, including set up and branding of operations

- Capital campaign costs (costs of fundraising, for example, donor events including tent rental, food and beverage, and security)

- Design Contingency (an additional percentage of the construction contract to cover the costs of unknowns early in the design process)

- Owner’s Contingency (an additional percentage of the construction contract to cover the costs of unknowns and unexpected conditions)

Sources of Funds

Once you have determined project costs, you have to determine how you will pay those costs. Many more routine projects are fully funded with public funds but for other, more complicated projects the sources of funds can be more complicated. As previously mentioned, since the 1970s, cities and the business community have turned increasingly to the Public Private Partnership (PPP or P3) model for the funding and development of projects that both sectors want but which the city no longer can solely fund with tax revenues.

Public realm projects can be large, small, simple, or complex. Funding varies too, between different types of projects. For example, funding for a park may come from one set of sources (such as state and local grants and private donations), while funding for a public street reconstruction project might come from another (federal, state, and local funds including assessments on property owners along the street). The following two lists identify types of FUNDS and types of FUNDERS:

Types of FUNDS

- Grants (Cash or proceeds from sale of bonds)

- Grants of land (Free or reduced price/discounted value)

- Clean-up grants (For environmental remediation/cleanup)

- Grants from bond proceeds (more to follow on bonds)

- General Obligation or “GO” (Gee-oh) Bonds (backed by taxing authority)

- Revenue Bonds (backed by project revenues)

- Assessment Bonds (Right Of Way Assessment for standard roadway Street and sidewalks, trees, lights, etc., paid by property owners)

- Special Assessment Bonds (Right Of Way Assessment for enhancements above standard roadway, such as lighting, street furniture, art, etc.)

- Special Assessment Bonds (For a larger area or district)

- TIF Bonds (For a specific TIF project or district)

- Private donations and gifts

- One-time donations

- Timed gifts (e.g., a fixed amount each year for five years – for donor’s tax purposes)

- Sponsorships and naming rights (e.g., US Bank Stadium, Target Field) (Naming can be for a whole facility but in many cases a number of smaller features within the larger facility are named after individual donors, for example, the Bob Smith fountain at the Jane Jones park)

Types of FUNDERS

- Government

- Local (General Purpose/City, Independent Park Board in MPLS)

- County

- Regional (In the Twin Cities, Metro Council, Metro Transit)

- State

- Federal

- Private Sector – Private Donations/Philanthropy

- Corporations, e.g., Target Corp.

- Corporate Foundations, e.g., Target Foundation, McKnight Foundation, Phillips Family Foundation, etc.

- Private Individuals (Gifts)

- Non-Profit

- Non-Profit Organizations (e.g., Trust for Public Lands – TPL)

- Foundations (e.g., McKnight Foundation)

The “Gap”

Sources of funds must equal or exceed uses of funds. If there are not enough funds the project cannot be completed and probably should not be started. For example, for a private sector development, if you do not have enough money to begin your project, then you will be unable to obtain a commercial construction loan or mortgage from a bank. In the public sector, if you do not have enough money to begin your project, then the government sponsor of the project (for example, the City) will not authorize you to enter into a construction contract to begin construction. Similarly, a superior government (for example the state of Minnesota) may not be willing to execute a contract for a grant or to distribute the funds until the sponsoring government (the City) can prove that they have raised the balance of the required funds. In this case the state’s funds are the “last in” funds. You don’t get those funds until you can prove that you have the balance of the cash first.

The equation is simple: Sources >/= Uses. If uses are greater than sources, then you do not have a viable project unless you can raise more funds or eliminate costs on the project. Here is a very simple sources and uses (S+U) table:

| SOURCES AND USES OF FUNDS | Viable Project | Dead Project |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of Funds: | $12,000,000 | $12,000,000 |

| Uses of Funds: | $11,500,000 | $14,000,000 |

| Gap: Sources Over/(Under) Uses | $500,000 | ($2,000,000) |

SUMMARY: Sources and Uses of Funds (S+U) and “the Gap”

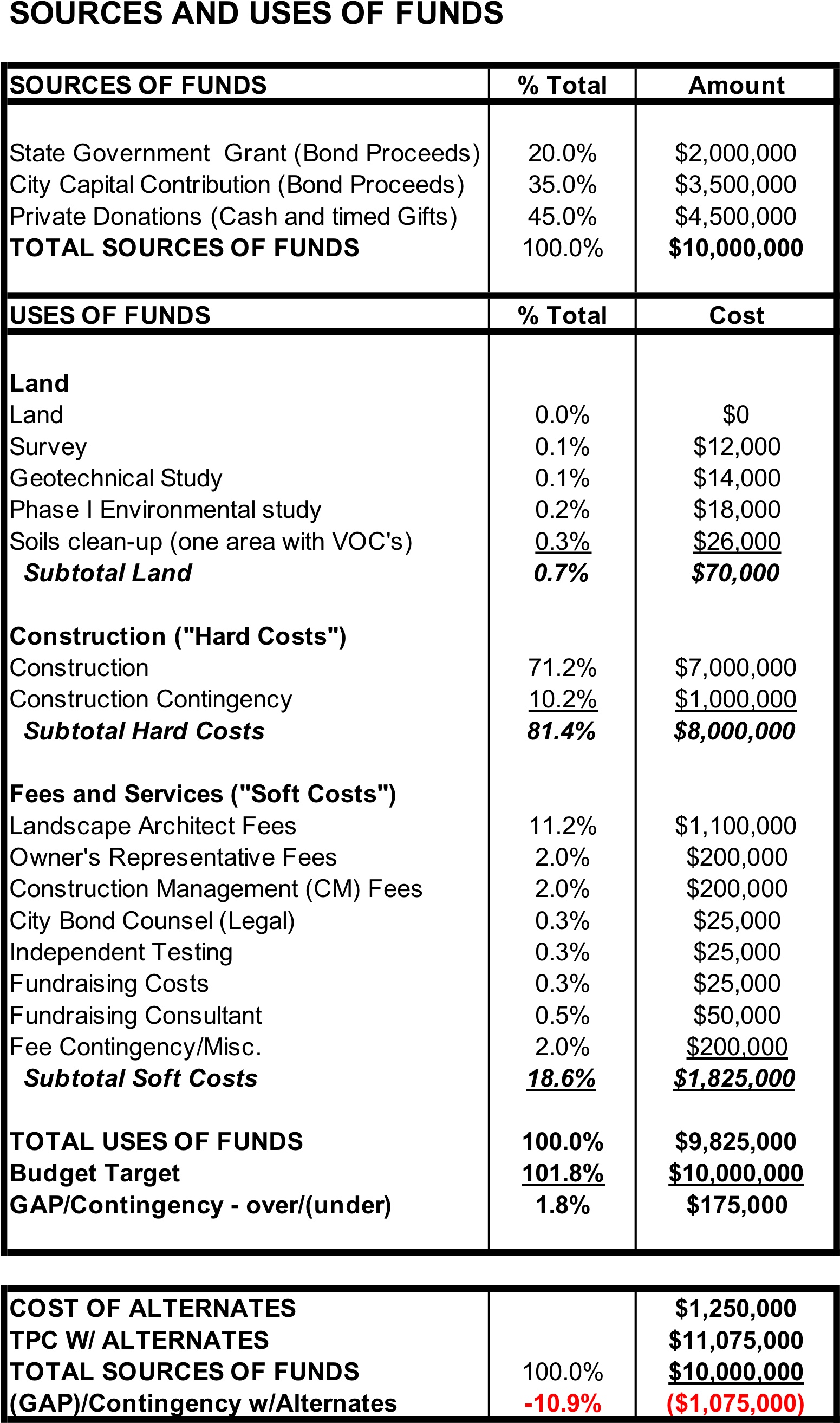

The following generic example is for a public realm project based on a public-private partnership model. There are two sources of public funds (state and local) and also private donations. The uses of funds include several potential “alternates” that could be designed and built if the funds could be raised. At the bottom, you can see that the Sources exceed Uses for the base project but that there would be a gap/or shortfall if the alternates were to be included.

This table represents the summary tab of a spreadsheet that would have additional detailed tables for each of the line items listed, with each table including much more detail. So, for example, there would be tables detailing each of the different consultant fees and one for all of the construction costs and contingencies. There would also be a table listing all of private donations and another listing all of the different coded sources of city funds that sum up to the total sources. A project may start with a simple table or worksheet but by the end there will be a full workbook that might have six to twelve detailed tables feeding the summary table. This project budget reflects a “base” project – the minimum required to complete the project – as well as several “alternates” or enhancements that would improve the project if the additional funds can be raised.

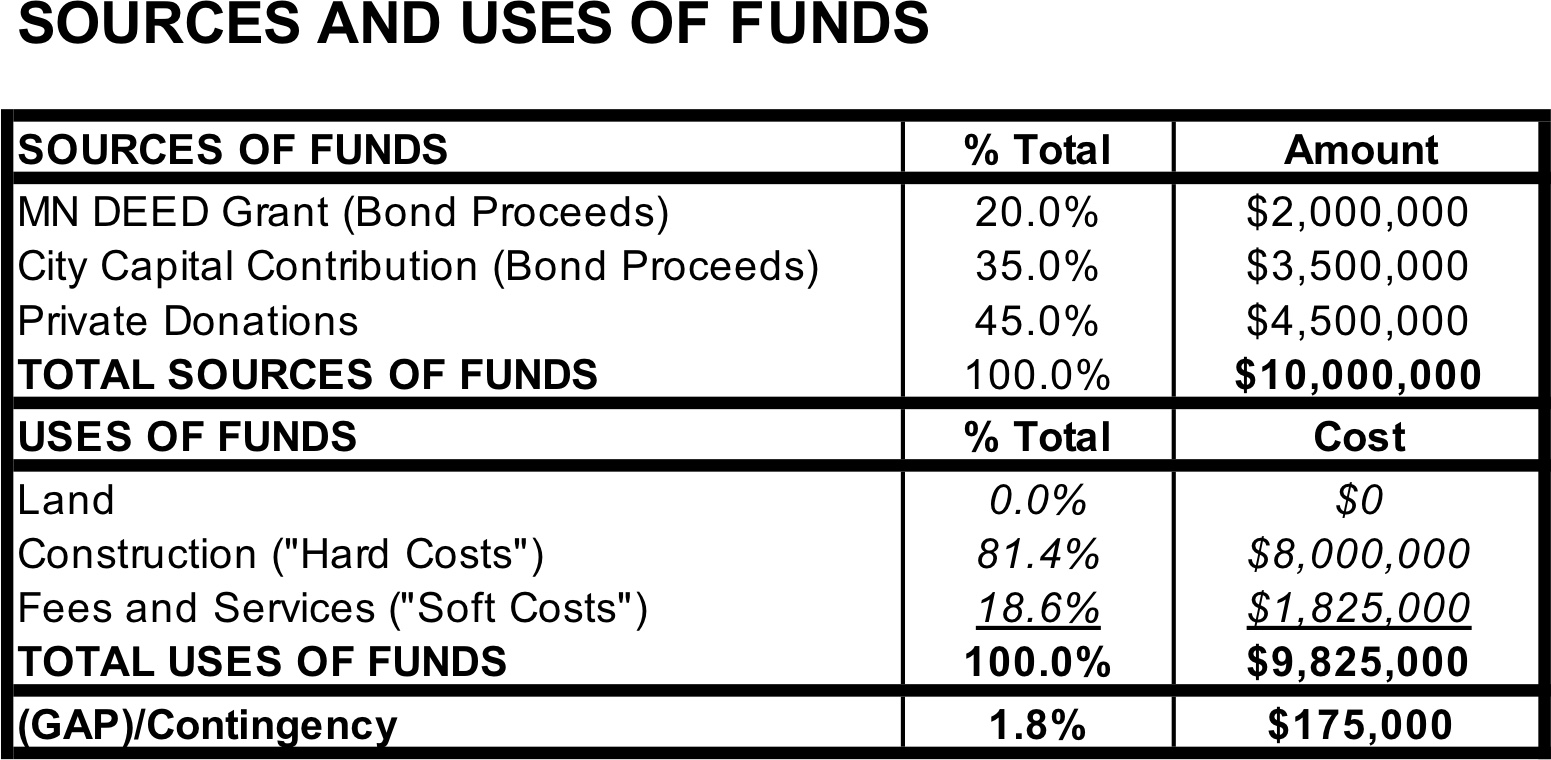

Below is a simplified version of the previous summary sources and uses table. What this table tells you is that if you can obtain all of the sources then you have more than enough money to complete the project although you do not have enough to compete the “alternates” from the previous table, which might include, for example, pavers instead of a poured concrete sidewalk or an extra feature such as a fountain. What it also tells you is that you better get to work raising $4.5M in private sources as well as doing the political work involved in ensuring that you receive the two public grants. And what are those $5.5M in bonds all about? What are bonds, anyhow?

- Consumer Price Index, 1913-, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/community/financial-and-economic-education/cpi-calculator-information/consumer-price-index-and-inflation-rates-1913. Accessed August 2, 2019. ↵