2.6 The Design Process

The lead design consultant for a public realm project is usually a landscape architect, an engineer, or an architect. The lead designer typically assembles the full design team and manages the process overall, working closely with and for the owner or client. The lead design firm will subcontract with other consultants including the landscape architect, architect, and civil engineer, as well as the structural, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing engineers, and other specialty design consultants such as lighting, soils, horticulturalists, water feature specialists, brand and graphic design, and others, as required for the project and based on input and approval from the owner.

The design team will then embark upon an iterative process, beginning with bubble diagrams describing programmatic relationships and adjacencies before moving to rough sketches and then ever more refined scaled drawings. The amount of detail and information grows throughout this iterative process. The design team and the owner together will constantly review and refine the design, along with periodic construction cost estimates, leading in turn to more revisions and refinements.

The lead designer will coordinate with the other consultants and incorporate their drawings and specifications into a single package of information. This package is typically called the “construction documents.” These documents are used to solicit bids from contractors to build the project. Later on, I will discuss more the different phases of the design process but for now, we will focus on just three key phases: concept design, detailed design, and construction. Concept design is the part of the project that attracts the most attention from the public, the media, and funders as it starts with blank sheets of paper and stakeholder input and results in a plan and renderings. Detailed design is more work but during this phase the look of the project does not change very much, rather, many detailed decisions are made regarding size, location and dimension of features, materials, and systems. Finally, the construction phase also attracts less attention unless it creates a lot of disturbance for the public as in the case of a street reconstruction. The opening of the project and its activation and operation will be discussed later. The focus in this section is on the part of the project that draws the most interest and attention from the most people – concept design, which begins with the program.

Program Confirmation

The first thing the consultant will do once they have been hired is to interview all of the key users, beginning with the people who were on the selection committee at the interview. The goal is to gather more detailed information than was included in the RFQ/RFP and to get a better understand of the motivations behind the project, and the objectives of the project’s sponsors. This is an opportunity to find out what someone meant when they asked a question in the interview, to identify potential conflicts between goals and users, and to get a better understanding of the underlying interests, politics, and funding constraints. The program itself is the document that describes the objectives for the project, the intent and function of the place, the allocation of space, the general features, the needs of the users, and any infrastructure requirements such as water, irrigation, lighting, roadway access, or public toilets. The program is subject to adjustment based on stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholder Engagement

The concept design phase will include public meetings and will start with an analysis of the existing site and bubble diagrams showing how different features and elements might be located and how they could relate to one another. As these ideas become fixed, the design will be refined until there is enough information to produce realistic digital renderings of what the place will look like when it is done. Planners on the design team and in government will assist with the design and implementation of the engagement process as well as with the management of the administrative processes. The concept design will be a communications and consensus-building tool that will help many people reach a point where they can support the project. There is a saying that “a good deal is one where all parties are equally dissatisfied.” The case is the same with designing for the public realm. The outcome will be a compromise and no one will get everything they want. But if the job is done properly, the project will satisfy most stakeholders and attract support, or at least not cause significant opposition.

Big Ideas, Diagrammatic Plans, and Renderings

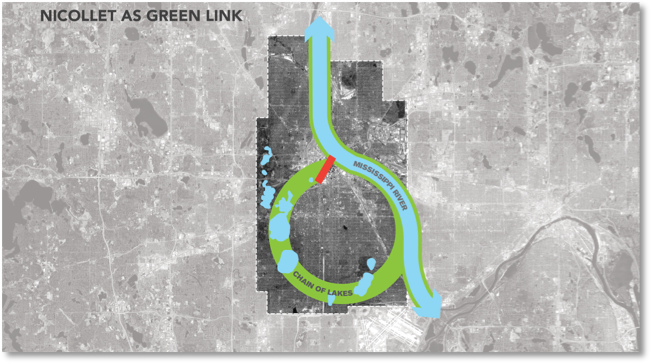

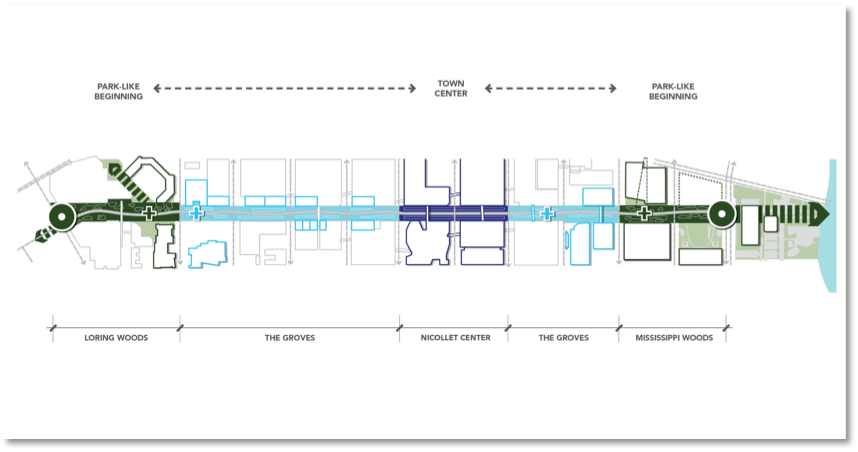

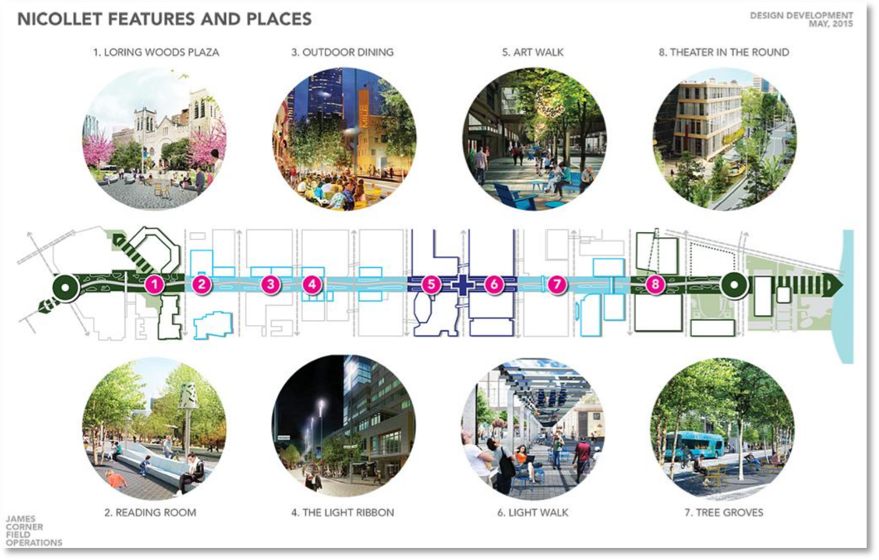

Good designers start with big, over-arching ideas and concepts that are easy to explain – and easy for the public to grasp. They then create diagrams that illustrate these ideas and last but not least, realistic renderings that people can understand. Below are three images from Nicollet Mall that illustrate the big idea, a diagrammatic plan, and what it might actually look like in person.

The Big Idea: “The Stitch” (shown in red) represents the designer’s idea that there is a big continuous loop of nature around Minneapolis but that it is interrupted in downtown. Their proposal was that Nicollet Mall would serve as a green stitch connecting nature from Loring Park to the River.

Diagrammatic Plan:

The second and third images are early and later versions of the concept plan – the designer’s idea of how to vary the design of the twelve-block, mile long street, from the north and south ends in nature to the most urban part of the downtown core, through three zones called the “woods,” the “groves” and the “center.” The woods are more informal and natural and have landforms, the groves are still informal but with more sidewalks, and the Center is very urban with straight rows of trees and other more urban architectural elements.

Renderings:

Finally, the last image is an early rendering of how the center area would look and feel if you were to be walking through it.

The Purpose of the Concept Design

The Concept Design for a public space must serve a number of functions. First, it must begin by offering a narrative and a vision that is clear, comprehensible, attractive, and that satisfies the wants and needs of most of the key constituents – it must generally address the functional needs of potential users as well as those of the future operators of the place. Second the concept design must attract political support. Third, the concept design must help raise funds.

Fundraising Brief or “Pitch Pack”

The design images created during the concept design phase will become the basis of a fundraising brief or “pitch pack.” The fundraising materials will include a simple “one-sheet” that can be handed out at presentations and at meetings with individual potential donors. There will also be a slide show that shows the big ideas, plan, renderings, schedule, and an overview of the design process as well as a conceptual budget.

Media Briefing and Information Package

Similar to the Pitch Pack and at around the same time, the City or owner may choose to send out a “press release” sharing the project goals and objectives, renderings, budget, and schedule. For big projects there may be a press briefing where members of the press are invited to a presentation by the project team and the designer to explain the project. In the case where there is sensitivity to timing of, for example, City Council meetings where the project will be presented for review and approval, representatives of the media may be given the renderings and information in advance with a strict embargo on their use – in other words – they are given the information in advance of an important meeting so that they can write their article in advance and then as soon as the meeting is over they can publish it, but they must promise not to publish the images in advance. The media creates stories and for a big project, one of the most important things you can do is make sure the media’s story is accurate and that it does not get ahead of your story or your process with incomplete or wrong information.

The Entitlement Process

One important aspect of any urban project – pubic or private – is what is called “the entitlement process.” Entitlements are all of the approvals you need to obtain from City government to be allowed to proceed with the project. And even if the City will be designing, funding, building, owning, and operating an urban public realm project, it will still have to seek approvals.

For example, a new park in an area zoned for commercial buildings may require re-zoning for park use. The new park may also be required to provide certain stormwater management systems if it is greater than a certain minimum size. There will also be minimum requirements for lighting that the city’s public works department will have to approve. The fire department may have opinions on how their vehicles may access the park and if any additional curb cuts are required. The design may also be reviewed by the planning commission to ensure that it conforms with design standards, and if there is a land use change, then the zoning and planning committee may have to weigh in and approve the request. The police department may want to review the project from a public safety perspective to determine if it adequately reflects the principles of “Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design” (CPTED). There may also be a need for a new drive entrance to the park that will require an easement as the vehicles will be crossing the public right-of way. Even signage is regulated by the the city and the number, size, type, materials and lighting of signs are all subject to approvals. There may also be advisory committees that will have opinions on the design. For example, in Minneapolis, the Pedestrian Advisory Committee (PAC), Bicycle Advisory Committee (BAC), and the Minneapolis Advisory Committee on People with Disabilities (MACOPD) are all typically invited to review designs as they develop and participate in early planning an design meetings regarding public realm projects.

For any project in the city of Minneapolis the owner must apply for site plan review through the Preliminary Development Review (PDR) process, where all of these issues will be discussed. Once you have satisfied all of the various requirements and received the final package of approvals, variances, easements, zoning changes, and related funding agreements, you have received all of your “entitlements” or your project has been fully “entitled,” which means you can complete design and then seek a construction permit and other related permits. This may include approval from the Planning Commission, Heritage Preservation Commission, zoning and planning committee, Transportation and Public Works Committee of City Council, City Council, watershed district, county commission, Metro Council, MNDOT, or the state. Obtaining these approvals may be very political and you may be required to solicit and earn the support of surrounding neighbors or local neighborhood groups, environmentalists, historic preservationists, and any number of formal or informal special interest groups whose representatives may appear in a public hearing to testify on your project, either in support of it or against it.

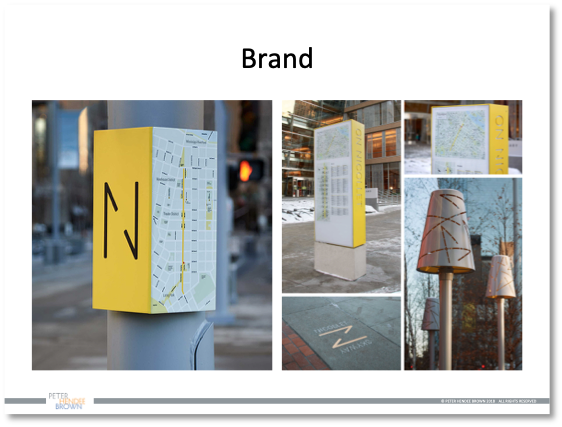

Narrative, Graphics, Brand

For larger projects, the creation of a narrative, an identity, and a “brand” for the project will become important as a way to highlight the project, generate support, and begin to create an identity for the project. The identity and brand will be used first to promote the project on materials from public meeting invitations to the design of the project’s website. As the design develops the brand will be refined and integrated into features that will be completed in construction. These may include anything from a chair with the project name on it to a logo on a physical feature like a sign or a light fixture.

Communications, Public Relations, Media

Another related process that requires attention and design thinking is that of planning for and consistently communicating with the many stakeholders over the duration of a project. Communications may include everything from public meetings, one-on one meetings, and block-by block meetings with property and business owners to solicit feedback and just keep people informed. There should also be a website with an FAQ and all previous design presentations available for public viewing. And there should be a plan for working with the media.

One of the most challenging aspects of a public project is the role played by the media – and social media – in covering, explaining, and offering critique of the project. Some stories are good, others are critical, and often they pop up suddenly and can become a big distraction for the project team, as everyone scrambles to provide an explanation for why, for example, so many new trees seem to be dying or dead. You can’t always plan for those surprise stories, but you can have a plan in place for who will talk to the media. You can also keep a current version of an FAQ document that can be used in explaining the project when responding to a particular issue.

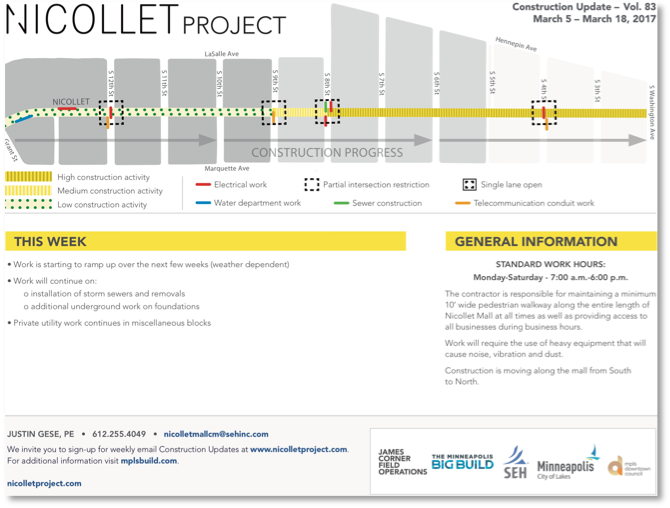

Another key part of the communications plan has to do with how, during the construction phase, you communicate with the property and business owners who are being directly affected by construction activity. For recent major street projects in Minneapolis, the city has used weekly stakeholder meetings to explain what work was completed during the previous week, what work would be completed in the coming two weeks, and how that work would individual stakeholders. The following map was revised every week for the Nicollet Mall stakeholder meeting to show generally how the work would impact traffic and access to buildings and businesses.

Detailed Design

In the previous sections I have discussed design in a variety of contexts and the idea and use of “design thinking” in project management. The purpose of this section is to describe the design phases as they are typically understood by consultants and described in consulting contracts. This is a narrower definition of “design” but it reflects how consulting contracts, scopes of services, fees, and payment are understood in the design and construction industry. The American Institute of Architects characterizes the phases of the design process as follows (Engineering design phases are similar but are expressed as simple % complete):

Programming:

The designer and owner discuss the goals, needs and function of the project, design expectations, budget, and relevant building code and zoning regulations. The architect prepares a written statement setting forth design objectives, constraints, and criteria for a project, including special requirements and systems, and site requirements. For a building a space program includes a list of all rooms and their sizes and functions as well as net square footages per room and overall gross square footage for the building. This information is used to establish a conceptual budget. The owner reviews and comments on the program and budget and then the designer revises and finalizes both. Once the owner has officially approved the program based on the feedback and revisions, the designer will begin Schematic Design.

Schematic Design (30% Design):

The designer consults with the owner to ascertain the requirements of the project and prepares schematic studies consisting of drawings and other documents illustrating the scale and relationships of the project components for approval by the owner. The designer also submits to the owner a preliminary estimate of construction cost based on current area, volume, or other unit costs. The owner reviews and comments on the schematic design and preliminary cost estimate and the designer revises and finalizes both. Once the owner has officially approved the schematic design and preliminary cost estimate, the designer will begin Design Development.

Design Development (60% Design):

The designer prepares more detailed drawings and finalizes the design plans, showing correct sizes and shapes for rooms. Also included is an outline of the construction specifications, listing the major materials to be used. An updated estimate of construction costs is also included. Once the owner has officially approved the Design Development and revised cost estimate, the designer will begin Construction Documents.

Construction Documents (90% Design):

Drawings and specifications (the construction documents) created by the designer that set forth in detail requirements for the construction of the project. Specifications are a part of the construction documents that are contained in the project manual and consisting of written requirements for materials, equipment, construction systems, standards and workmanship. An updated estimate of construction costs is also included. The Design team does a coordinated check of their own drawings at the same time that the owner reviews and comments on the drawings. Once the construction documents have been completed, the owner, with the assistance of the design team, will “bid” the work to qualified contractors (or negotiate with one or two). These contractors will analyze the documents in detail to determine amounts and quantities of material and equipment as well the amounts of labor by trade that will be required to build the project.

Bid/Negotiation/Award/Contract:

Contractors submit “bids” for the project to the owner and, under a traditional public bidding process, the bids are opened publicly in a bid room, at a specific time, and read out to those in the room. Usually, a project team member and all of the bidders attend the bid opening but anyone may come and, for a really large and important project, someone from the media may attend. The lowest qualified bid wins the project. The city procurement staff must evaluate the bids as well as civil rights staff (for minority business participation) and then, once qualified, the low bidder is awarded the contract. The city and the contractor negotiate and execute a contract for construction that includes the total price of the work and a scheduled completion date.

Construction:

Once the contract has been signed, the contractor begins to mobilize and takes over temporary control of the project site. Demolition comes first followed by excavation, utilities, and generally the work proceeds vertically from the bottom of the hole up. Last come structures, fixtures, buildings, light poles, and so on. There are actually two completion dates for construction. “Substantial completion” is when the work is about 95% complete. The contractor and owner agree that the project is substantially complete. At this point, the owner takes back control of and responsibility for the site (which has been under control of the contractor for the duration of construction project) and re-opens it to the public.

Following substantial completion, the contractor is required to provide a complete set of Operations and Maintenance (O&M) manuals to the owner, explaining how all systems are operated and maintained and including “as-build” drawings of the project. Many changes happen during construction to adapt to field conditions, unexpected changes, owner-directed changes, and other things unknown during design, and it is the responsibility of the contractor to keep track of these changes – and what was actually built and where. The owner will use the as-built drawings in the future for operations and maintenance. Following substantial completion, the contractor may be on site completing small fixes and repairs or installing items that took longer to arrive, but this will be relatively minor activity. Substantial completion also triggers the start of the warranty period, which is typically one year for most systems and materials. The contractor must replace any work that fails within the one-year warranty period (dead trees, cracked concrete) at no cost to the owner.

Closeout:

Throughout the warranty period, the owner withholds a very small portion of the contractor’s total contract amount – called “retainage” – as a way to ensure that the contractor has an incentive to complete any unfinished work and honor warranty repair work. At the end of the warranty period the final payment is made to the contractor(s) and the contract is closed out. If the contractor for some reason does not complete the work or honor warranty work, the owner can use the retainage to hire another contractor to complete this work.

“The Three-Legged Stool:” Quality, Cost, Schedule (you can have two out of three)

In the design and construction industry, there are three, inter-connected variables that an owner (or anyone else who plans to build) must pay attention to: cost, schedule, and quality. There is also a commonly held understanding that an owner may only ever have real control over two of these three variables. Thus, while you may be able to have a high-quality project delivered at a relatively low cost, it may take a long time to complete, because contractors, subcontractors, and laborers are not financially incented to perform and other, more profitable projects are attracting their attention. Or, you may be able to get your project delivered quickly and at a reasonable cost, but the quality may be less than you had hoped for, because the contractor must settle for less when it comes to available labor and materials. Finally, you may be able to have a project that is high-quality and delivered on a fast schedule, but you can be sure that it will be very costly, as the contractor will be required to pay top dollar for labor (including overtime) as well as for materials and equipment that may be costly to fabricate and deliver quickly. Based on these rules, consider the replacement for the collapsed 35W bridge vs. the new Guthrie Theater. Which variables do you think the owners of the two projects prioritized?

All three variables are important to any owner and one must work to determine the best mix of the three. While the reality is grayer than simply saying “if you want it fast and cheap then the quality is going to be poor,” it is helpful to think in these terms when making decisions about design and construction. Do you really need that fancy marble from Italy that is going to take sixteen weeks to quarry and ship and will cost three times as much, or would Kasota stone from Mankato work just as nicely and play better politically too, since it’s locally sourced and more sustainable?