3.5 Debt Financing and Bonds

The quote at the beginning of the chapter says, “Finance allows us to move economic value forward and backward through time. That enables humans to plan their lives, both individually and collectively.” That’s the idea behind borrowing. Excessive credit card debt is a bad idea but borrowing to buy a car, home, or college education are examples of the idea of moving money back and forth through time and using finance to help plan your life. Imagine how much more challenging life would be if you had to pay cash every time you wanted to buy a car?

Although some owners or clients can completely finance a project’s total capital costs with cash, most cannot and many others choose not to. One reason to borrow is that you cannot afford to fund the project all at once, but for cities and governments another, more important reason to borrow is because it effectively spreads a very large one-time cost into a series of much smaller monthly or annual costs (payments) that reflect the use of the asset over time. In other words, if you will enjoy the use of a home for 30 years, why not pay for it a little bit every year over those thirty years – similar to paying rent (although you also benefit from the appreciation in value over time) – since this breaks down the total cost of the home and connects your use of it over time with your regular income over time.

Another way to think of it is that few people have the ability to plunk down $266,000 for a home (the median home price in Minneapolis) but some people can afford to come up with a single down payment of 10% ($26,600) and then pay $1,400 per month for 30 years. The relative value of that payment drops over time as inflation and your income both rise, but the payment amount stays the same, so the last payment feels pretty small when compared to the first one. (The added benefit of homeownership is that the value of your home rises over the term of the mortgage, too, so when you sell you profit from appreciation.)

Borrowing for capital projects usually involves the selling of investment instruments called bonds. Bond financing is used in both the public and the private sectors. For example, in the private sector, a company may sell corporate bonds to finance the construction of a new factory with the idea that the increased production capacity from the new factory will allow the company to sell more product at a lower cost per unit, increasing income and profits over many years to come. The company therefore agrees to repay those bondholders a little bit of their principle plus a percentage of income each year with the expectation that the factory is generating increased income and profits for the company. If things going according to plan, the company will be able to pay down the bonds and still earn greater profits than if they had never built the factory in the first place.

On a more personal level, debt financing of a major capital project is no different than taking out a loan to buy a car, home, or student tuition. Rather than paying cash when you buy something costly, you borrow the full amount and repay it over time. For education, your increased income over many years to come because of your education makes the investment worthwhile. Similarly, why pay for a car all at once if you can pay over time so that you have more reasonable annual costs that reflect the use of the vehicle over time?

The case is the same in the public sector, except that the income is tax dollars. Cities sell bonds backed by future tax revenues and they repay those bonds, a little bit every year, over the term of the bonds (20 or 30 years) with tax revenues from future residents/taxpayers. The city’s annual operating and capital budgets take into account annual “debt service” (repayment of debt, similar to a car payment, student loan payment, or mortgage payment) along with payroll and other annual operating costs.

The effect is that everyone who lives in the city and pays taxes at some point or another is paying for the share of the project that they may use during the time they live in the city. In this case if you live in the city and pay taxes for years 23-26, you are paying for a share of the project but the costs are spread out over time. The alternative would be to pay for a major capital project in one year, which would be unfair to the taxpayers who lived in the city in year one and who paid a whopping tax bill that year and who would be unfairly privileging all of the other people who don’t have to pay it but get to enjoy the “asset” or “improvement” or “facility” for the next twenty-nine years.

The big idea is that investors purchase bonds that are backed by some future revenue stream that will repay the bonds plus a little income. The investors take a risk but for city bonds, and particularly General Obligation bonds, the risk is slight because the bonds are backed by the taxing authority of the city, which means that the city can always raise taxes, if it must, to service its debt.

Types of Bonds

A bond is an investment instrument sold by a government or corporation to investors who will receive a guaranteed payment over a period of time. Over the course of a 20-year bond, for example, the bondholder receives a regular fixed payment (monthly or annually, for example) that includes repayment of the original principal plus interest income. For public bonds, this income is not taxable, which lowers the cost of money for the city (the interest rate) while appealing to investors with wealth who are seeking to lower their tax burden. Tax-exempt municipal bonds may earn 4% against 8%-10% in the stock market, but there is little volatility, the likelihood of repayment is very high, and you do not have to pay taxes on that 4%. Corporate bonds are sold by private companies, usually for the purpose of financing major, long-term investments such as a new factory but the interest income is taxable so corporate bonds must offer investors a higher interest rate, for example 6%. Both corporate and government bonds are used to finance long-term permanent capital investments. The repayment of the bonds is known as “servicing the debt,” and the monthly or annual payment is called the “debt service.” Refinancing or paying off bonds completely before they come due or their term is up (for example, paying off the balance of 20-year bonds after 15 years) is called “defeasing the bonds.”

Debt service is a part of a city’s annual operating budget, along with payroll, fringe benefits, leases, supplies and so forth. Cities sell bonds every year and so the city always has debt service on multiple bond issues, some new, some half-way paid off, and some that are about to be paid off or defeased. Cities usually take on new debt as they defease old debt so that debt service is always a part of the budget. For example, the City of Minneapolis is about to complete repayment of debt on the central library – and take on approximately the same amount of new debt for the purposes of funding a new city office building and renovations to City Hall. Around election time you may hear a lot about ballot questions in suburban cities for large bond issues for new schools. Taxpayers may worry that their taxes are about to go up but often the new debt is just replacing old debt, and won’t change your tax bill much.

Municipal or “Muni” Bonds

People invest in bonds because they expect to be repaid the principle and earn an additional tax-exempt income (say 4%) for taking the risk of investing. Government bonds are usually considered to be low risk because governments rarely default on their bond repayments. This is because government can use its taxing authority to generate the income required to repay the bonds or, in other words, it can raise taxes if necessary to repay its debt. If the city has trouble repaying its debt or if it defaults on its payment, the rating agencies (Moody’s, Fitch, and Standard and Poors) will downgrade the city’s credit rating from, for example, a Fitch rating of “AAA” (the best), to a rating of “AA+,” which signals to investors that the risk is higher. [1]

When the risk is higher, investors will require a higher rate of return to justify the higher level of risk of the investment. Anything rated BB+ or lower is investment grade or “junk bonds,” that offer a much higher return but a much higher risk, including the risk of the total loss of the investment. Cities do not want their credit rating lowered because lower ratings mean higher required returns from investors and increased costs of borrowing in the future – basically paying more to get the same thing. For example, if a AAA bond rating means it costs $1.04B to borrow $1B in bonds, and a AA+ rating means it costs $1.05B to borrow the same amount – a difference of $10M – the City is highly incented to maintain that AAA rating because $10M is a lot of money.

People invest in assets that are backed by a future stream of revenues that ensure the likelihood of repayment. For example, you might invest in corporate bonds because you are assuming that the company you are investing in will grow in value and income and be able to repay you and the other bondholders. For your own mortgage, the bank is assuming that your employment history and income is a good indicator of your ability to repay a thirty-year loan from your ongoing income. However, in the case of a home mortgage, the loan is also secured by the value of the asset, the home, so if you default, the bank can foreclose and then sell the home to recoup the loaned funds (the bank’s depositors’ funds) from the proceeds from the sale. So, people invest or make a loan when they know there is something other than wishful thinking giving you the idea that you will be repaid. The big idea is that bonds are backed by an estimated or projected future stream of revenues – profits, taxes, rents, fees or charges. There are many different types of bonds, so here are the basic types:

General Obligation or “G.O.” (“Gee-oh”) Bonds

There are two basic types of bonds that are often used for public projects: General Obligation (“GO”) Bonds and Revenue Bonds. Every year cities sell GO bonds backed by a future stream of projected tax revenues. The city’s bond rating is important because it establishes the cost of money (the income on the principal) so most cities will do anything – including raise taxes if necessary – to cover debt service payments. That is a really powerful guarantee of repayment and because they are so safe, GO bonds earn a lower interest or income rate – say 4%. Income from G.O. bonds, however, is tax exempt, so for people with wealth who are trying to minimize their tax burden, they can trade a lower income for the tax-exempt status of the investment. For example, a 6% bond that is taxable may be yield a similar net return as that if a 4% bond that is not taxable.

Revenue Bonds

Revenue bonds are typically also issued by a government but they are project-based and are backed by a projected future stream of revenues from specific user charges, fees, rents, or tolls. Revenue bonds are used to build toll bridges and tunnels, public aquariums, ballparks, parking facilities, convention centers, and other things for which users can be charged directly. (Compare to tax-based G.O. debt-financed facilities that anyone can use without paying a charge, like a park, street, or library.) Revenue bonds are considered the second safest type of bonds after G.O. bonds and the reason they are not as safe is because repayment is backed by specific project revenues and not by taxing authority. Further, the revenues are not guaranteed and projections are often overly optimistic, so risk varies based on the project. For example, a toll bridge is very safe investment if there are only so many routes across a river. However, a highly speculative tourist attraction such as an aquarium, can be much riskier. Because there is more risk involved, investors in revenue bonds may expect to earn more like 6% as opposed to 4% for GO bonds (the income is still tax exempt). In a local example, the Saint Paul Port Authority developed parking ramps using revenue bonds. Another variation is Industrial Development Revenue Bonds (IDRBs), which may be used for projects such as converting old polluted industrial land into new light manufacturing and warehouse uses to create new jobs and generate new taxes from underutilized property.

“Moral Hazard” and “Moral Obligation” Bonds

An important concept surrounding revenue bonds is the idea of “moral hazard” or “moral obligation.” Revenue bonds are often issued by special purpose governments like public authorities (such as the Saint Paul Port Authority), rather than by general-purpose governments (the city or state). However, despite being back by a future stream of revenues from a project and not by taxes like GO bonds, investors and Wall Street perceive revenue bonds as being nearly as safe because in the case of poor performance or default, the unwritten expectation is that in the end the city will cover the debt – with taxpayer dollars. The reason for the city to cover the debt is that, in the end, in the case of default, the bond rating agencies may move to downgrade a city’s credit rating if one of its agency’s or affiliated government’s bonds default.

This is why Revenue Bonds are sometimes called “moral hazard bonds:” Revenue bonds can shift the risk to cities and taxpayers if the project fails. If, for example, a city’s economic development authority uses revenue bonds to finance an aquarium and the bonds are backed by ticket sales that never materialize, the city may end up bailing out the aquarium to avoid having its own credit rating damaged. This is more of an issue in cities that have numerous special purpose governments such as parking authorities, industrial development authorities, and so forth. The Saint Paul Port Authority (SPPA) and the Saint Paul Housing and Redevelopment Authority (HRA) are both examples of independent local authorities that issue bonds but are also both entwined with the city (several city council members also sit on the port authority board and the HRA board is the complete council with a different council member serving as chair).

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Bonds

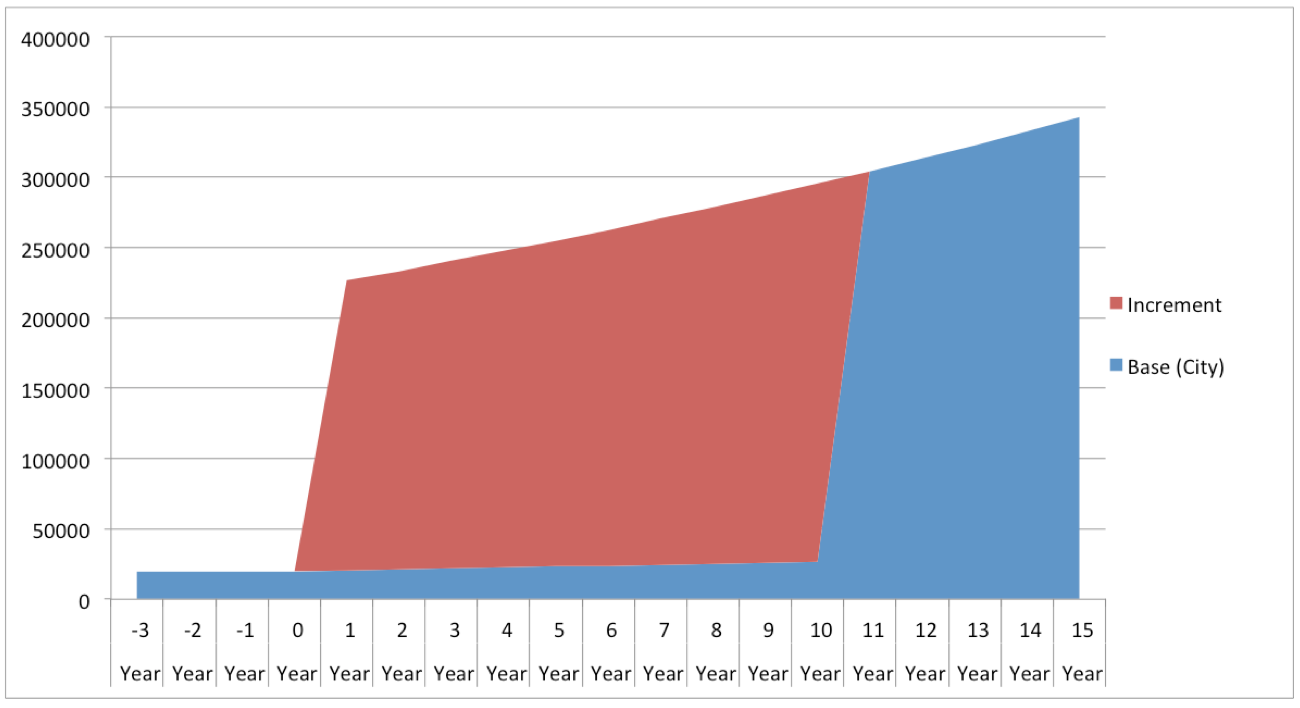

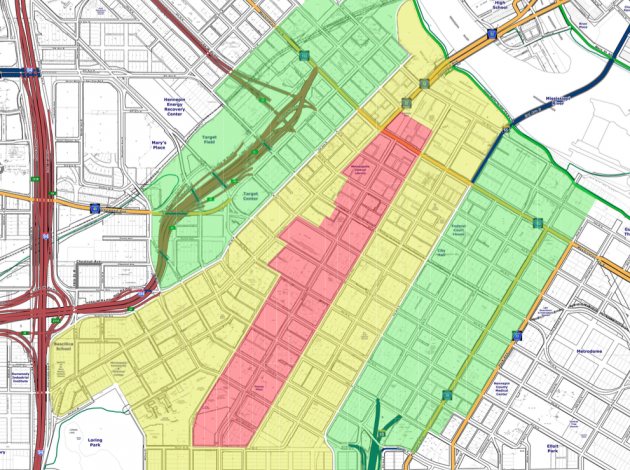

TIF Bonds are backed by the future tax revenues that will be generated by the new project or projects within a TIF District. The district can be a single parcel/project or it can be a large section of a city where all projects contribute to the district. The difference between tax revenues from a current parking lot and a future high-rise office tower on that lot (for example) is called “the increment.” The city agrees to forgo receipt of that increment for some period (ten or twenty years, for example) and instead uses those future real estate taxes to repay the TIF bonds. TIF bonds are usually used to subsidize a private sector development project or a PPP but they are meant to be spent on public amenities, such as parking, street furniture, and the public realm surrounding the project. “Public purpose,” however, can be interpreted broadly. In Philadelphia during the 1990s, a number of early 20th century historic office buildings were TIF’d and re-purposed as hotels. The amount of subsidy required was so great that the public portion of several new hotels included not just the streetscape and public parking, but also extended into the main lobby, the elevator lobby, the elevator lobbies on all floors, and the corridors on all floors – all the way up to the doors of the private rooms.

Assessment Bonds

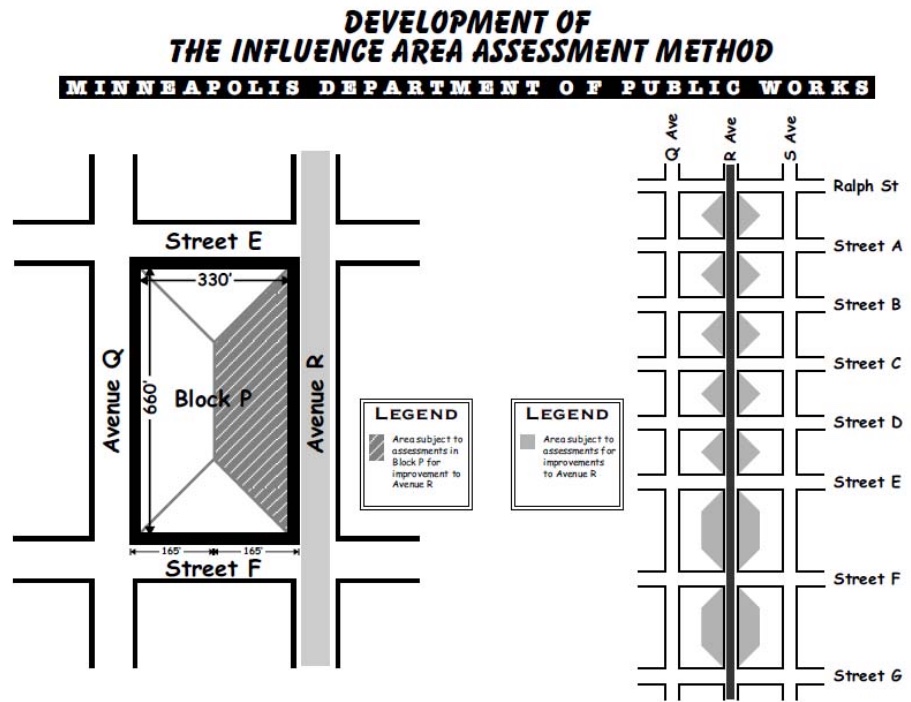

A city may sell assessment bonds to finance a road or a water system or some other improvement or facility that serves a specific group of property owners who are then assessed. The assessment appears on the property owner’s tax bill. The bonds are backed by the collected assessments. The diagram below shows how assessments are calculated based on a share of the footprint (in square feet) of the property facing the street.

- For more, see “Bond credit ratings,” on wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bond_credit_rating accessed August 2, 2019. ↵