4.5 Stakeholder Engagement Process

I covered the stakeholder engagement process in Chapter 2 – Design, but since it is such an inherently political process, I want to repeat here that planning and implementation for stakeholder engagement is one of the most important things to get right when it comes to planning and design for the urban public realm. People are more sophisticated than ever and can smell a non-genuine or “box-ticking” engagement approach from a mile away. More important, a good stakeholder engagement process can do a number of great things for a project – and a place – from improving the design (with genuine user and stakeholder feedback) to cementing political support (“P”, “p”, and “bureaucratic”) and attracting funding. Most important, the stakeholder engagement process cannot be rushed.

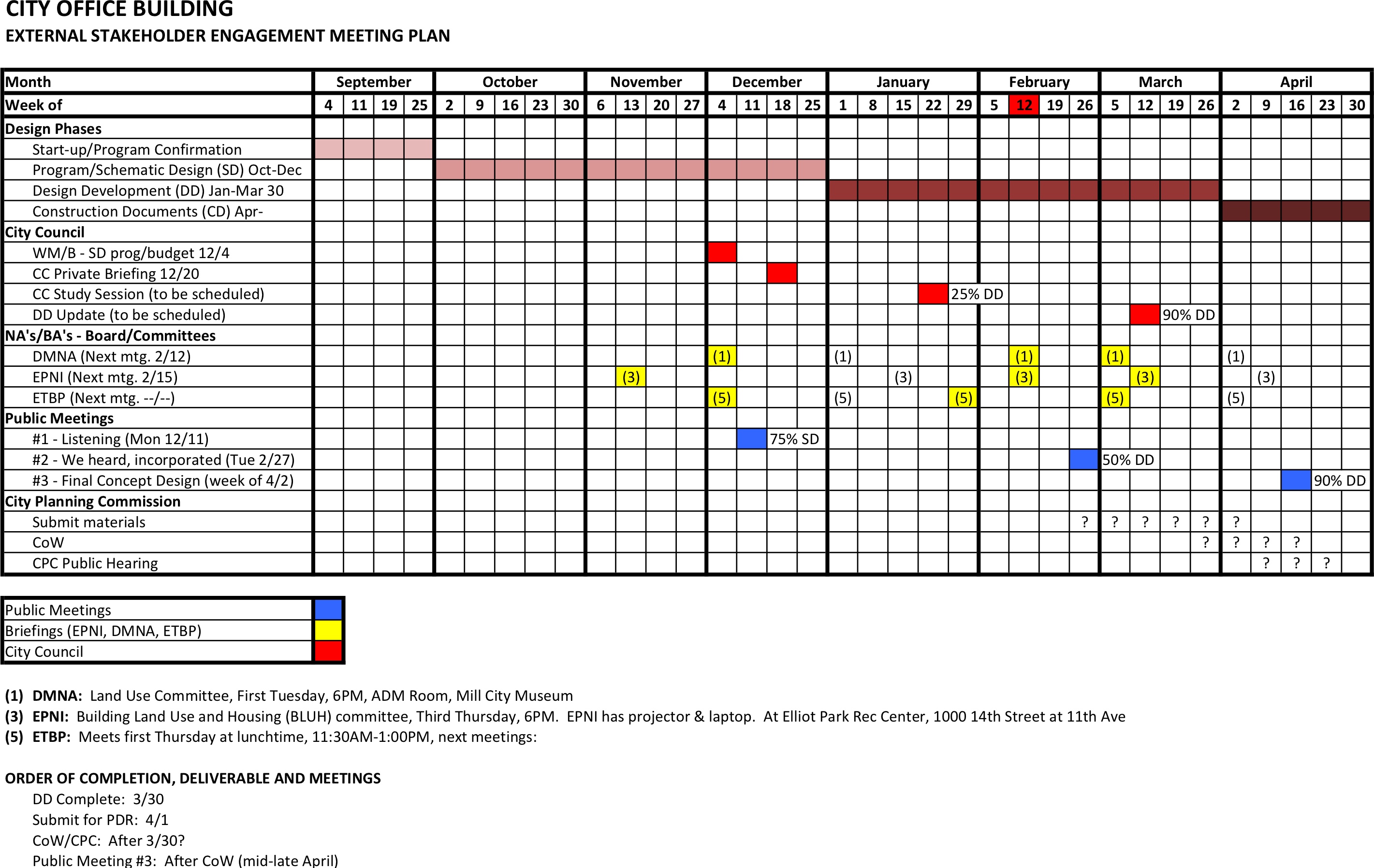

For the Minneapolis Public Service Building or PSB, a new City office building located across from City Hall that will be completed in 2020, the project team was not sure who, if anyone, would be interested in the project. Members of the public often are interested in design and aesthetics as well as massing and height but in truth, there were no real nearby neighbors or property owners who seemed concerned about this major project. Still, when complete, the PSB will be a facility that is open to the public and that will consolidate all public-facing city business into one building with a grand lobby. Further, there will be a conference center that may be used by the public and a public art program as well. The City’s project team created a plan and schedule for stakeholder engagement that ran roughly in parallel with the major milestones of the design for the project, spread over six months and three major public meetings.Below is the stakeholder engagement schedule for the new PSB. In addition to using social media and other outlets to reach the broader public, the team focused on communicating with the two neighborhood associations and the one business association that operated in the area (the project is on the border between neighborhoods) as well as on the general public.

The program was based around three big public meetings, two months apart each, with briefings of the neighborhoods and business association in advance of each public meeting. All of the meetings were open to the public. The three major public meetings were held in the same location, the in lobby of the Mill City Museum, in one of the neighborhoods and a few blocks from the project site. Approximately 35 people attended each of the three big public meetings and about half of them were members of the project team, so about 18 members of the public – and mostly the same people for all three meetings. Compare this to around 200 for the public meetings for the Commons, which were held in the same room two years before. Prior to the meetings, the project team had no idea how many people would come, who would come, and if there was any natural constituency interested in the planning and design of the project. The City ordered nine tables and 90 chairs for the first public meeting and by the third meeting the numbers had been reduced to 50 chairs and coffee and cookies for 35.