4.6 Summary: How Do Things Really Work?

Graham Allison and the Essence of Decision

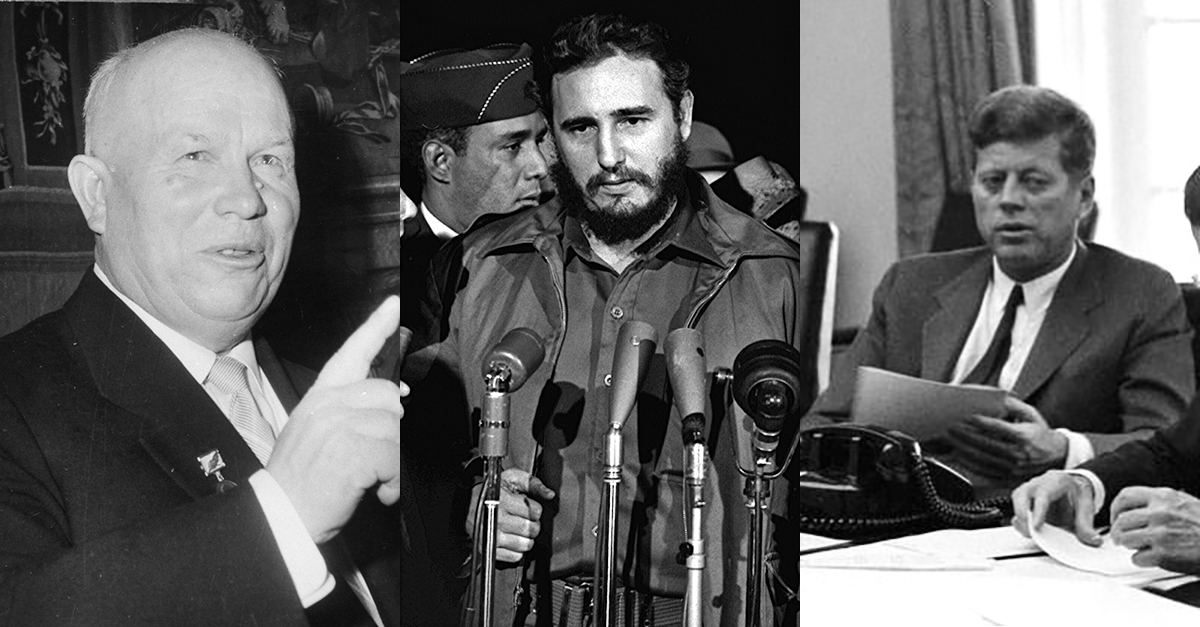

At the height of the cold war, in the fall of 1962, an American U-2 spy plane flying over the Island of Cuba took photos that, when analyzed, showed that Russian missile bases had been constructed there, just 90 miles off the coast of the continental United States. During a tense two weeks, Russian and American leaders – President John F. Kennedy and Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev – and their governments found themselves in a tense standoff and had to find a way to work together to extricate themselves from a difficult situation and avoid nuclear disaster.

Graham Allison was a PhD candidate at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in the 1960s when he wrote a dissertation on the events that became known as “the Cuban Missile Crisis.” He rewrote his dissertation as book called Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, which was published in 1971 and became a bestseller and a critical success. (Allison published a revised, second edition in 1999.) [1]

Allison was interested in how governments function and how decisions get made but he found existing theories to be lacking in explanatory power so he devised a brilliant study. He created three detailed case studies of what happened during those two weeks in October 1962, each looking through one of the three different existing theoretical lenses. Reading the book is like reading the same story three times – yet each version of the story is different from the others but still completely true and relevant. Only when considering all three stories together do you get a sense of what actually happened – a kind of 3D picture over time.

Allison’s book was important because it offered a critique of the weaknesses of the three competing theories of foreign relations and exposed the flaws and blind spots in each theory, By using the events of October of 1962, he was able to illustrate how the three theories, when combined, had more explanatory power. Allison’s study considered the three predominant theories at the time, which he characterized as: the “rational actor” theory, the “organizational process” theory, and the “governmental politics” theory. These theories apply as easily to local governmental processes and decision making today as they did to foreign policy in the 1960s. Here they are.

Rational Actor

The “Rational Actor” theory is based on the idea that states behave like individual human beings and that they are rational actors. This theory personifies large organizations, states, and countries but it oversimplifies and misrepresents decision-making and action by dismissing how fragmented large organizations are and how they are made up of bureaucratic groups and key individuals with different and often competing or conflicting interests. For example: “Cuba allowed Russia to build missile bases on the island, Russia shipped missiles and supplies to the bases, and the US responded by imposing a naval blockade surrounding Cuba .”

Applied locally, “The City proposed this, the designer drew that plan, and the neighborhood group reacted by opposing a part of the plan.” It presumes that groups are unified and speak and act as if each group is a, single, integrated, individual rational human being. It is an elegant model and easily used for shorthand, in the news for example, when you hear reports that, “China and America are engaging in a trade war.” But Allison’s point is that this is a dangerously simplistic model that leaves out much of what happens within and amongst bureaucratic agencies and with key individuals.

Consider the example of the Commons, from earlier in this chapter. The “rational actors” were the Minneapolis Sports Facilities Authority (MSFA), Ryan Companies, the City of Minneapolis, The Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board (MPRB), and the state of Minnesota Legislature. Yet within each organization there were both staff and elected leadership (commissioners, council members, mayor, legislators) and many other stakeholders. The outcomes were not driven just by these five individual agencies each acting like a rational individual, but by many other actions and interactions between and among agencies and individuals.

Organizational Process

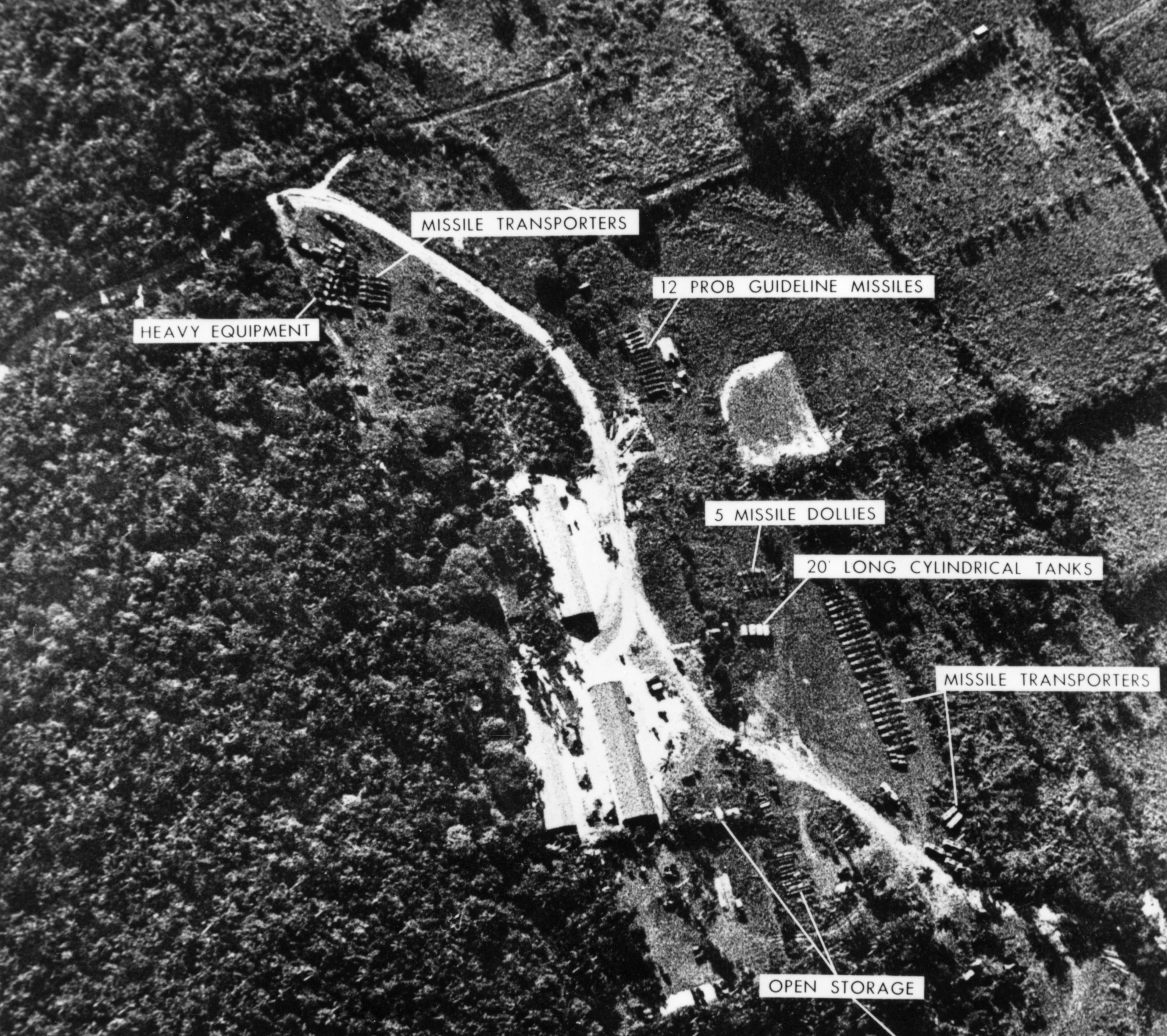

The “Organizational Process” theory argues that decision-making and action revolve around bureaucratic organizations – agencies within government – that rely upon “standard operating procedures” (known well in bureaucratic organizations such as the military as “SOPs”) for much of their work. An SOP-based answer to the question “why?” is, “because we always do it this way.” SOPs are fine for typical and often repeated conditions but ill-fitted to more unique situations and contexts. Failing to adapt SOPs to different and sometimes inappropriate contexts without too much questioning can lead to real problems. Here is a “we always do it this way” example from the Cuban Missile Crises: The USSR’s bureaucratic missile base planning department relied on SOPs and designed and built a standard-issue Russian Missile base on Cuba – missiles here, transports here, launchers here, storage sheds there, barracks over there. It is literally a cookie-cutter pattern.

The problem is that from 70,000 feet up in a U2 spy plane, all Russian Missile bases the world over look the same and the US intelligence analysts who review the photos taken from the plane’s cameras know that pattern when they see it. A creative thinker in Russia might have said “hey, let’s make this missile base look different and maybe try to hide it since it will be so much closer to the US and they will know what it is when they fly a U2 spy plane over it.” But when organizational processes and SOP’s dictate, there is no room for creativity, so despite Nikita Khrushchev’s bold idea (missiles 90 miles from the continental US – that should change the balance of power!), it was effectively defeated by a bureaucratic apparatus over which even Premier Khrushchev had little power.

Lots of the public realm is streets and sidewalks and public works departments all over the world have SOPs. That said, public works people are sometimes willing to try new things (really!). But on the other hand, just because the mayor (or Khrushchev) says “I want it this way” doesn’t mean it will happen that way.

I previously mentioned how on the Nicollet Mall project, the Director of Public works gave the team permission to design signal poles that were not painted green and yellow. Two years later, the shop drawings for the poles were passed through for review prior to actual fabrication. This is a routine bureaucratic step where the architect, lighting consultant, engineer, and client (the city lighting department) review and make any red marks to the fabricator’s detailed drawings to make sure that they are providing what was ordered before the material gets produced. One team member who had been around during design, two years before, happened to be in the room when some staff had off-handedly been discussing the fact that the lighting department guys had marked up the drawings to require yellow and green paint. They were not trying to be purposeful or insubordinate, they just did not know or remember – and it was their SOP to do it that way. They probably thought someone had forgotten to specify the green and yellow paint and they were correcting that mistake. No one else there had been there two years before and so that team member said, “wait, they are not supposed to be painted that way” and the drawings were corrected. If that one person had not been in the room that day, the poles would not have been what the city leadership and all of the stakeholders who had worked on the project for four years had wanted to see on the project. If you believe that details matter, you can begin to imagine how this kind of thing can happen – all the time.

Governmental Politics

Finally, the “Governmental Politics” model focuses on the politics and negotiations that occur between individual political leaders within governments and it assumes that much of the action is driven by a handful of key individuals with their own unique perspectives and objectives as well as personalities, egos, and interests – for example staying in power. Khrushchev put missiles in Cuba, Castro encouraged him to do so, and Kennedy responded to the Soviet Union’s aggression with a naval blockade.

In fact, Kennedy and Khrushchev used a back channel – a Russian operative speaking through a close aid of the Kennedys – to carry communications between the two of them because as the days passed, they both became increasingly at risk of losing control to their own governments. Khrushchev wanted to find a way to get out of the mess he had created but he did not have support from the politburo, which was became increasingly hawkish as the days passed, so he needed Kennedy to help him find a face-saving solution to offer to his colleagues.

In the end, Kennedy agreed to remove some obsolete missiles from Turkey – on the edge of Russia – which gave Khrushchev the appearance of a win and the political cover he needed with his own government to remove the missiles from Cuba. In this model, individual political actors with lives, careers, and their own perspectives and interests drive all of the action and the decision-making.

On a recent local project, some members of the business community led by one business leader had promised to raise a certain amount of funding for a public-private project. They had not yet met their goal and it began to look like the city would have to make up the difference (the city already had committed a large share of money to the project based on the promise of private fundraising). The city staff person running the project briefed the Council Member who then had a lunch meeting with the business leader where it was made clear that the city’s share depended upon the private share being fully raised. Those two people had their reputations at stake and wanted to see the project successfully completed, so they brainstormed and thought of several more potential donors. They went together to ask those potential donors and one of them made a significant gift while several others gave as well, effectively completing the raise. In this case, the key individuals who had been publicly promoting the project had reputations to protect, egos, and a shared interest in seeing the project successfully completed and had to work together to find a solution – and they did.

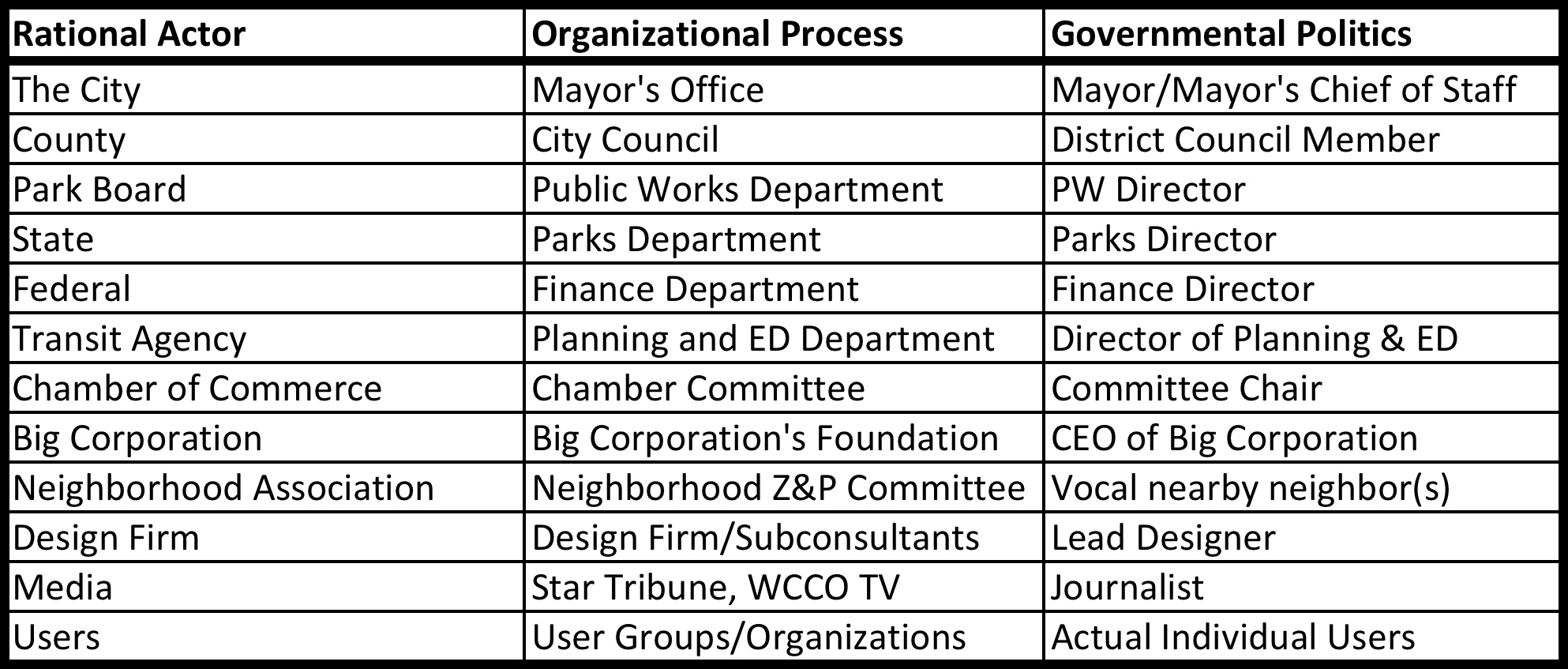

Allison’s three lenses are just as useful for viewing local political action – and projects – as they are for considering foreign affairs. So, for example, a typical project may have this combination of these three types of actors:

In the work of implementing any public project, you may find it helpful to think in terms of all three of Allison’s lenses. First, which government(s) and private organization(s) are involved and what are their roles and powers? Second, which agencies – the staff doing the work – are responsible for executing the project and what are their SOP’s and bureaucratic cultures? Third, who are they key people involved and what are their professional and personal interests in and beyond the project? And last, once you have answered those three questions, how do you overlay the answers to create a picture of who’s doing what and why? How can you use that three-dimensional political picture help you to plan for and implement your project?

- Allison, Graham T. and Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis, Second Edition, Pearson, 1999. See also Kennedy, Robert F., Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, New York: Norton, 1969. ↵