An Introduction to Producing the Urban Public Realm

Purpose

This book was written for use by University of Minnesota students of PA 5290, Planning and Design for the Urban Public Realm. This book is a companion to the class readings, which will expose you to a broad range of ideas and concepts – from the theoretical to the applied – around the experience and production of the urban public realm. As a complimentary and alternative view to the readings, this book will reveal to you the nuts-and-bolts reality of how places get built – from the original idea through planning, design, funding, construction, turnover, and day-to-day operations. The specific purpose of this book is to provide a simple framework for understanding project implementation – how to conceive of, produce, and operate new urban public realm projects in the 21st century American city. This manual does not reference many other sources, rather, it is a summary of “field notes” – my own experiences and observations about how recent public realm projects have been implemented in Minneapolis.

Perspectives

The Perspective of this book

This book takes the perspective of the practitioner – the planner or designer – responsible for implementing a new urban public realm project. The purpose is to help that practitioner understand, plan for, and respond to all of the many forces that influence a public realm project. The objective is to help the practitioner increase their own chances of creating a project that is successful in the eyes of the many different project participants and stakeholders. Finally, rather than focusing on worthy aspirations of how things ought to be, this book takes the perspective that the practitioner must understand how things work in the real world today if they are to succeed. And to be clear, success in this context means a completed project.

Your Perspective – the Ethnographer

In the social science field of “ethnography” (the study of a group of people based on immersive field work) it is a common practice to begin a book with an introductory chapter that details the researcher’s own experiences as a way to illuminate their personal history, perspectives, biases, and blind spots. The idea is that one cannot study a social situation or a group of people (a study called an “ethnography”) without first cataloging and acknowledging one’s own “baggage” and laying it out for the reader. For the purposes of this course, think of yourself as an ethnographer. Attempt to be objective in your work but at the same time integrate your own experiences and perspectives and view the public realm through your own personal lenses.

My Perspective

I was trained as an architect and worked in architecture for 12 years. I worked in several different firms from very small (eight people) to very large (550 architects, engineers, interior designers and other professionals and support staff). I worked on a broad range of project types from a 400 square foot house addition to an all new, 1.5 million square foot, 10-building, $325M pharmaceutical R&D campus for a major drug company. During my time practicing architecture, I worked on single family homes, hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, commercial office buildings, corporate interiors, and pharmaceutical R&D laboratories. My projects included master plans, programs, additions, alterations, and all new facilities. By the time I left architecture I had worked on a number of very large projects, an experience that would influence my future work.

I then spent four years working in Philadelphia City government managing city capital projects – hiring and managing architects, engineers, and contractors to renovate and build new city facilities. These projects included window replacements in historic fire stations, a new police station, a new police forensic science lab (in a renovated, formerly abandoned elementary school), the exterior renovation of Philadelphia’s historic, 1.2 million square foot City Hall, and the complete gut and renovation of a 450,000, 18-story office tower into new space for 2,500 city employees. The clients and departments I served included police, fire, fleet management, and administration. While at the city, I studied government administration and then I left to study planning full time. Upon moving to Minneapolis, I worked in real estate development for four years, during the housing boom of the late 2000s, before working on the Orchestra Hall expansion project. For the past ten years I have worked as an independent project management consultant and much of my work has been on public realm projects for the City of Minneapolis.

So, my perspective is that of an architect who switched over to the other side of the table and learned how to be the owner – both for government and then for developers and other private and non-profit clients. I have helped hire and manage not only my own fellow professionals – architects – but also engineers, landscape architects, interior designers, brand and creative agencies, and communications and media consultants. I have also learned how the cultures, values, and methods vary amongst the different professions and disciplines. I believe that this broad experience has exposed me to the strengths and weaknesses of my own profession and made me a more objective and open to understanding how each of the other professions sees things – and sees one another.

Running a project can be like managing a zoo – you need to have both the tigers and the monkeys (and the snakes, sharks, and pandas, too) but you also need to keep them from eating one another. I have worked on large and small projects; new projects, renovations, adaptive reuse and historic preservation; and I have worked for private clients, government clients, non-profit clients, and real estate developers. Over the past ten years I have worked primarily on large, complex, public-private partnership-driven, urban public realm projects in downtown Minneapolis. Because I have worked in government and studied it, I have a good idea of what government people are trying to accomplish and how to work with and communicate with them. At the same time, because of my private sector experience, I have a pretty good idea of what the business community and private individuals are trying to accomplish.

My blind spots are that most of my projects have been large, costly, signature, downtown projects. While I understand operating budgets and work with operators, my perspective is skewed towards the capital project and planning, design, and construction. Because I live and work downtown, I get to experience the city and the places I have worked on, for better and for worse: When you walk by it every day, you are constantly reminded of things you wish you had done a little differently. Also because of where I live and work and the things I have worked on, I have a very downtown/urban perspective but I have little experience with small, local neighborhood parks, for example, other than visiting them and using them with my family (which we do all the time). I also have government experience but it is all with large central cities and mostly with Philadelphia and Minneapolis. I have worked with the county, met council, and state, but only in relation to the local projects I am working on.

An old and very successful real estate developer once told me that, “a successful project is a completed project,” and I agree. Some projects are wrong-headed and I try not to work on those, but if the basic idea at the start is right and you can support it personally and professionally, then it is worth finishing. There is nothing more disappointing than working on something for years that is never completed. On the other hand, if a project doesn’t seem right, you should think twice about working on it in the first place.

Roadmap

This book is comprised of this introduction, four core chapters, and a conclusion. Each of the core chapters will focus on a different nuts-and-bolts subject, from planning and design through finance and politics. The chapters build on one another although the subjects of these chapters do not necessarily occur in this neat chronological order, as all of these issues must be considered in parallel throughout the duration of a project, from inception through design, community engagement, fund-raising, construction, grand opening, and ongoing, day-to-day operations.

A Proposition

The flight to the city is on, and to enhance both productivity and quality of life in our cities, we must invest in our urban public realm. Many of the 75 million members of the millennial generation are abandoning their suburban upbringings and demanding a new urban lifestyle, complete with new real estate product types for living, working, and playing, all with an emphasis on shared social spaces – inside and out. Many of their parents – the 74 million baby boomers – are demanding similar things. Together, these two cohorts represent nearly half of our population and they will reshape our cities in powerful ways.

Cities will need to reinvest in older parks, plazas, and streets, but they will also need to provide new public spaces in developing areas that never had them – waterfronts, industrial sites, rail yards, and acres of surface parking. As important will be the re-envisioning of the public right-of-way – the street – as a place that accommodates not just cars but multiple transportation modes including cars, buses, rail, and bicycles, all integrated into a pedestrian-friendly and green environment. The greening of city streets will become critical for the creation of lush and livable places while also producing social, economic, and environmental benefits. At the same time, the production of the public realm must address resource use and climate change by minimizing the use of water, power, and other non-renewable resources while managing stormwater runoff, reducing light and noise pollution, and providing opportunities for landscape and habitats.

Perhaps most important, the work of improving our public realm will require commitment to multi-disciplinary collaboration and broad and genuine stakeholder engagement processes at an entirely new level. Complicated public realm projects will require a form of project team leadership that relies more on a form of representative democracy than on the grand vision of a single designer. Facilitating this process – and successfully building this new public realm – will require uniquely skilled and open-minded planners and designers who can help us envision a better way to live together in our cities.

The purpose of this course will be to help planners, designers, and other city builders come to understand the opportunities and challenges of project implementation – taking a plan from inception through planning, design, construction, and grand opening to public use and ongoing improvement – through the lens of a specific project type: The urban public realm project.

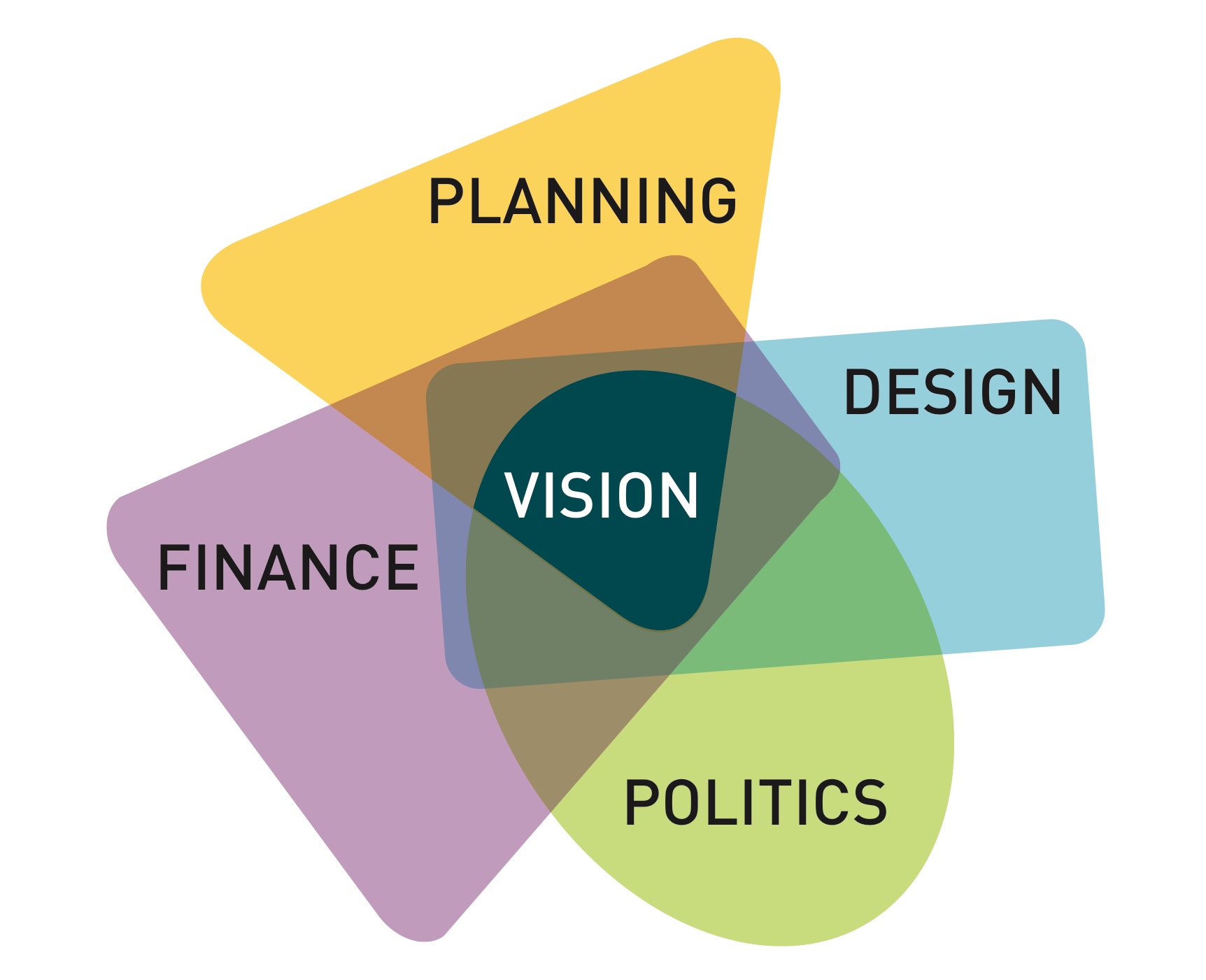

A Framework

Since the purpose of this chapter is to introduce the implementation half of the course, let us begin with a framework for your consideration. This framework argues that, for the successful completion of an urban public realm project, we must create a vision that clearly and consciously considers planning, design, finance, and politics. I propose that a vision that neglects any of these dimensions is a one that will not be realized. For example, a great design that lacks political support simply will not get built. Similarly, a design that does not attract political support will not attract necessary funds. Let us consider each element of this framework.

© Peter Hendee Brown 2019. All Rights Reserved.

Planning (Can you envision a clear path through to completion?):

Planning in this model means project planning. We are not yet concerned with formal “planning” in terms of comprehensive plans, zoning codes, or regulatory processes – we assume that if we can manage the design, finance, and politics of the project, that we will be able to find a way through those traditional planning processes. Nor are we concerned yet with the “community engagement” aspect of planning – that is critically important but we will address it later under the subject of politics. Project planning here means figuring out all of the little steps, processes, and decisions required to move the project from a glimmer in someone’s eye through the assembly of the project team, hiring of a designer, the management of a genuine engagement process, the creation of a compelling concept design, the funding of the project, the completion of design and construction, and the turnover and start-up of normal day-to-day operations in the new space. A public realm project can take many years to complete and there will be many twists and turns, so while you cannot plan the entire process from beginning to end, you must be able to identify a path through to completion and, if you cannot, then you should reconsider starting. As with all of the elements of this framework, planning is constant and ongoing from the beginning of the project to the end and overlaps and runs parallel with design, financing, and politics.

One of the first and most important steps at the beginning of any project is for the leadership team – the elected officials, key staff, and the public and private stakeholders promoting the project – to come to agreement on a set of key principles and a vision for the project that can be expressed clearly and succinctly with words. If you cannot explain the project with on one or two slides and a twenty-second “elevator speech” then you may not be ready to start.

Design (Can you create a design that generates broad support?):

The purpose of the design phase is to translate the vision created by the project leaders into a physical, three-dimensional design that everyone can visualize, understand, and support. The first step in this process, however, is to use the principles and vision as the basis of a selection process for a qualified project design team. Once the designer is on board, they will complete a site analysis and interview users and key stakeholders to develop a program for the new place. For example, it may be a grassy park, a bike facility, a water feature, a plaza, or some combination of those things. The design team and project team together must come to an understanding of how the place will be used and by whom. These studies will lead to a series of designs, beginning with very conceptual diagrams and ending with highly rendered images, with community and stakeholder engagement at each step of the way. The final design must be a legible, coherent idea that people can understand and explain and that is beautiful. It must offer features and amenities that make sense for its users, such as play structures, protected bike lanes, water features, and food and toilet facilities. The design must also reflect its place in the community, be legible, and create a sense of place. In the end, people need to be able to first understand and then accept, own, and promote the design. The design must satisfy potential users, nearby neighbors, the larger community, elected officials, and other key stakeholders and funders. The design is one of the most important elements in generating funding and political support for the project. A good design may be realized but a poor one can result in disagreement and division and no one wants to support or fund something that some of their neighbors and friends hate.

The design must make sense and be attractive to a lot of different people and, if it does, you may just be able to raise enough funds to build it. It is important here to note that different people have different ideas of what “good design” looks like and the designer’s idea of good design may not always reflect what the community members and other stakeholders want.

Financing (Can you attract the funds required to build and operate it?):

It takes a lot of money to build a new public place and it also takes a lot of money to run it once it has been completed. It is easy to think of a park as being relatively cheap compared to a building, for example. All you really need to do is sprinkle some grass seed around and buy a goat, right? Wrong: Public realm projects – even grassy parks – are expensive to build and expensive to operate and maintain. So, who’s going to pay for it? First of all, sources of funds for a capital project (the design and construction of the public space) are different from those used for ongoing operations. Public realm projects are often “public-private partnerships” (“PPP” or “P3”), as they are funded with a combination of government funds (federal, state and local tax revenues and proceeds from sales of bonds) and private dollars – corporate, foundation, and personal donations. In a later chapter we will learn about the difference between a capital and operating funds, “sources and uses of funds,” bond finance, the timing of cash flows, and the role of public-private partnerships. Regardless of the details of finance

Big public projects cost a lot of money to build, own, operate, and maintain, and if you cannot create a realistic budget and then envision how you will raise the substantial funds required to cover those costs, you should think twice about beginning. There is no amount of good design or good will that will result in a completed public realm project if there is not a realistic plan for paying for it.

Politics (Is there enough political will and public support to complete it?):

Politics in this context means everything from “Capital P” politics (elected officials) to “small p” politics – stakeholder engagement and a lot of one-on-one relations. Small-p politics may include working with nearby property owners, the neighborhood association, and other special interests such as the cycling community, pedestrians, the disabled, and environmentalists. Last but not least, politics includes bureaucratic politics – the relationships between government officials and between and among agencies and departments. Key people in bureaucracies play very large roles in the success or failure of projects and some are important power brokers in their own right. In the end, there must be enough political support for the project if it is to succeed. This includes everything from the elected officials who must vote to allocate public funding for the project to the nearby neighbors who must support it.

Big public realm projects often require the support of the mayor, the district council member, and the whole city council, but they must all have the support of the community, too, and the project team and designers must do everything they can to generate that support.

Vision = Planning + Design + Finance + Politics

The vision always considers and balances these four elements. Projects take a long time to complete and go through many twists and turns. Elections happen, key people come and go, funding changes, designs evolve, construction costs increase, and so on. Over the course of a project you must become accustomed to and comfortable with the constant fluidity, ambiguity, and uncertainty of the process and recognize how a million little changes will influence each of the elements of this framework over time. You must adapt constantly to these little and big changes, shifting two degrees left then three degrees right, but throughout you must always “keep your eyes on the prize.”