7 Abdomen 2: Bovine and Camelid

Revised Spring 2024 by T. Clark

Additional Resources for this Chapter:

- Related Supplemental Large Animal Surgery links: LAS Choosing a surgical approach; LAS Local anesthesia; LAS Rumenotomy; LAS Bovine Abdominal Exploratory on Right; LAS Small ruminant and Camelid GI disorders; LAS Abdominal contour; Bovine GI Surgical disorders; LAS Abomasal displacement; LAS Hardware disease

- Veterinary Gross Anatomy Ungulate Dissection (Abdomen Labs 11-14)

- Helpful Dissection Videos:

- Dried Ruminant Stomach (6:29)

- Dried Camelid Stomach (4:12)

- Embalmed Bovine Abdominal Viscera (17:03) – note misspeaks: in this video, the caudate lobe of the liver was misidentified; at 7:10, it should say “abomasum”, not “omasum”

- Fresh Bovine Abdominal Viscera (19:26)

Objective

A7.1 Identify and describe the structures and organs of the abdomen in bovine; describe the normal topography of the abdomen and localize the related internal and external structures and organs.

A6.1 describes similar structures in the equine abdomen that would be found in the bovine abdomen.

Abdominal Wall Muscles and Structures

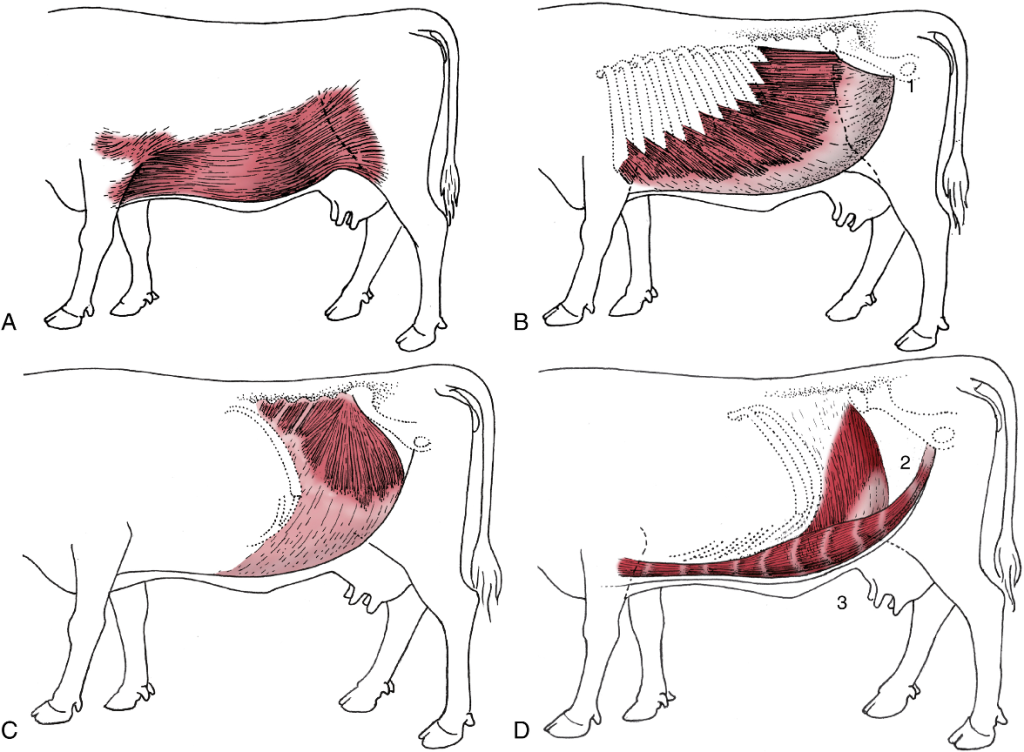

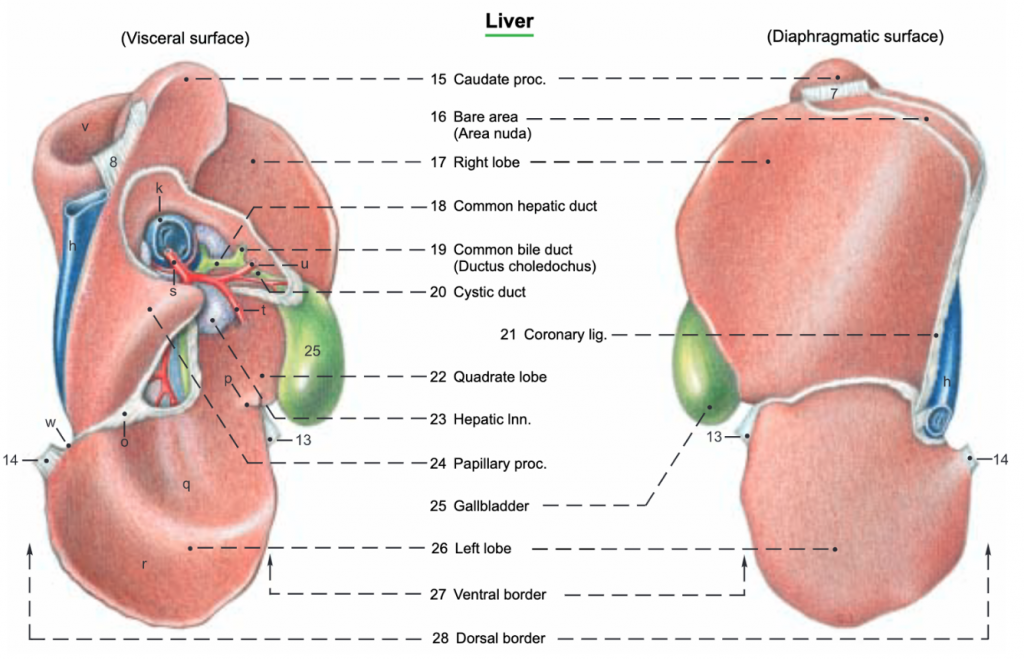

FIG. 28.1 Cutaneous trunci and abdominal muscles. (A) Cutaneous trunci, especially well developed ventrally. (B) External abdominal oblique with superficial inguinal ring (1) in its aponeurosis. (C) Internal abdominal oblique. (D) Transversus abdominis (2) and rectus abdominis (3). Note the reduction in the thickness of the wall along the caudal part of the rectus margin. TVA

- The subiliac lymph nodes (bov) are found at the cranial edge of the thigh muscles, about midway between the tuber coxae and the fold of the flank. (Fig. 31.10)

- The paralumbar fossa (ID in bov, but also in eq) is the most common surgical site for entry into the ruminant abdomen. It is a triangular depression bounded by lumbar transverse processes and the epaxial muscles dorsal to the processes, the last rib, and an oblique muscular thickening of the internal abdominal oblique m. extending from the tuber coxae to the costal arch. (see image below)

- Clinical Notes: paravertebral nerve blocks (proximal and distal) can be performed to numb the paralumbar region (i.e., flank) in BOVINE for exploratory procedures or left displaced abomasum (LDA) procedures. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Choosing a surgical approach; LAS Local anesthesia)

FIG. 31.10 The lymph nodes of the bovine pelvis and hindlimb. 1, Lateral iliac lymph node; 2, coxal lymph node; 3, medial iliac and sacral lymph nodes; 4, deep inguinal lymph node; 5, gluteal lymph node; 6, ischial lymph node; 7, tuberal lymph node; 8, superficial inguinal (mammary) lymph node; 9, popliteal lymph node; 10, subiliac lymph node; 11, linea alba. TVA

Figure above – stethoscope placed in the left paralumbar fossa of a bovine.

Abdominal Membranes and Other Structures

- Connecting peritoneum connects the parietal and visceral layers, or the visceral layers of adjacent organs and can form peritoneal folds called ‘mesenteries’, ‘omenta’, or ‘ligaments.’

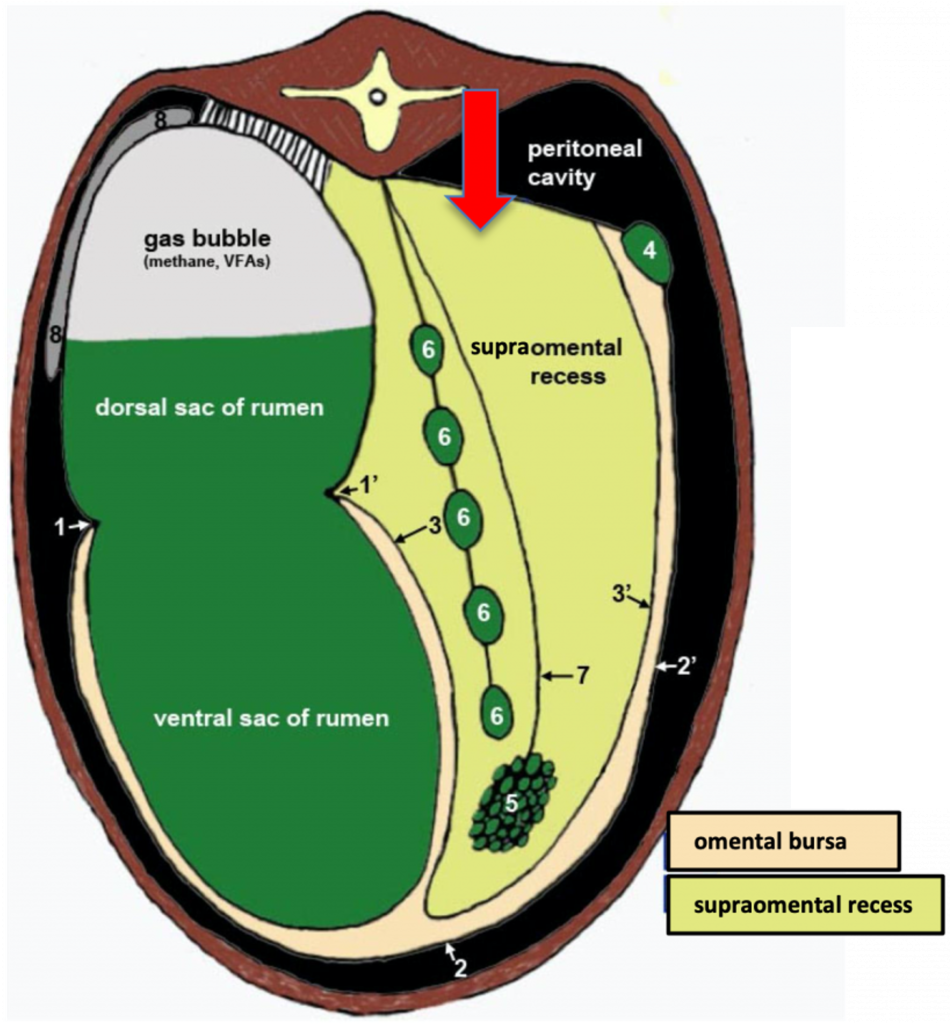

- The greater omentum and lesser omentum are connective tissues associated with the greater and lesser curvatures of the stomach. In bovine, a sling is created by the greater omentum allowing for the GI tract to sit within a space called the supraomental recess (see further discussion and image under Connecting Mesenteries of the Bovine Stomach in Objective A7.3).

- The mesoduodenum, mesojejunum, mesoileum, and mesocolon are mesenteries wrapping the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon, respectively. The root of the mesentery is at the center of these mesenteries (and has the cranial mesenteric a. running within) and is a point of firm attachment to the dorsal body wall, however the small intestines are still relatively mobile.

- Typically in bovine, the mesenteric lymph nodes are found within the mesojejunum, and there is usually a distinct line of them near the edge of the jejunum.

Figure (above) showing examples of mesenteries (e.g., mesocolon); the “root of the mesentery” is at the center of each figure of the GI tract.

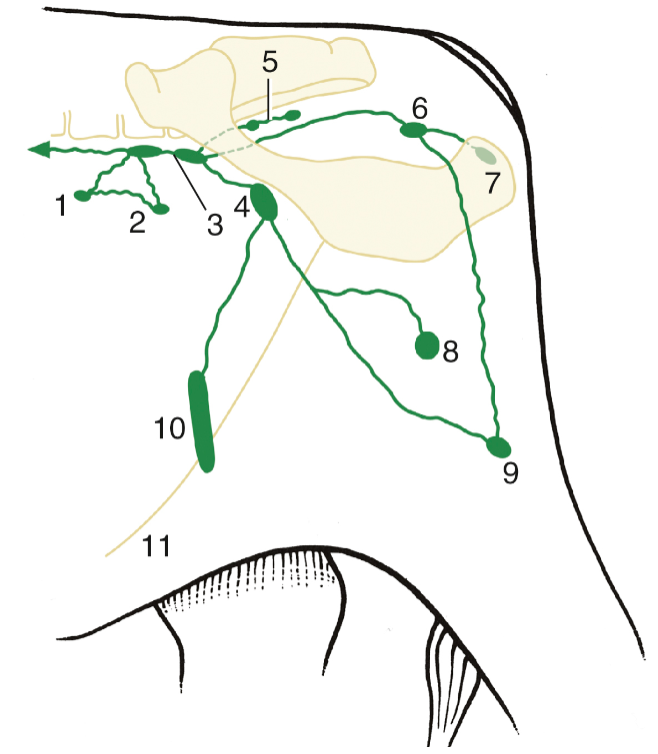

- Liver: bovine have a gall bladder and bile exits the gall bladder through the cystic duct, combines with the hepatic ducts, and all join to form the bile duct. There are three main liver lobes: right, left, and caudate lobes. An indistinct quadrate lobe is located between the right and left lobes.

- The portal v. delivers nutrient and metabolite dense blood to the liver for filtering. The hepatic vv. exit the liver and empty into the caudal vena cava.

Figure (above) Visceral and diaphragmatic surfaces of the bovine liver. Labeled structures: caudate lobe (24, papillary and 15, caudate processes); 17, right lobe; 18, hepatic duct; 19, bile duct; 20, cystic duct; 22, quadrate lobe; 25, gall bladder; 26, left lobe. (Budras & Habel Bovine Anatomy)

- Within the wall of the duodenum, there is a major duodenal papilla, which allows the bile duct and main pancreatic duct to enter into the duodenum.

- The pancreas is situated relatively dorsal making it hard to find if the GI tract is still attached to the dorsal abdominal wall. The pancreas has two lobes that join centrally at a body. The left lobe is along the liver, while the right lobe is within the mesoduodenum along the descending duodenum.

- BOVINE kidneys are lobulated, which is due to the retainment of the developmental lobes, as most kidneys start as lobes and then fuse. The left and right kidneys are tucked in fat and hidden along the dorsal body wall (i.e., retroperitoneal).

- The right kidney is located ventral to the last rib and first few lumbar transverse and is retroperitoneal. The left kidney of ruminants is pushed to the right side by the expansive rumen and is located ventral to the third-fifth lumbar vertebrae. It hangs down medial to the dorsal sac of the rumen. Therefore, the left kidney is not retroperitoneal as kidneys usually are. Both kidneys are embedded in fat.

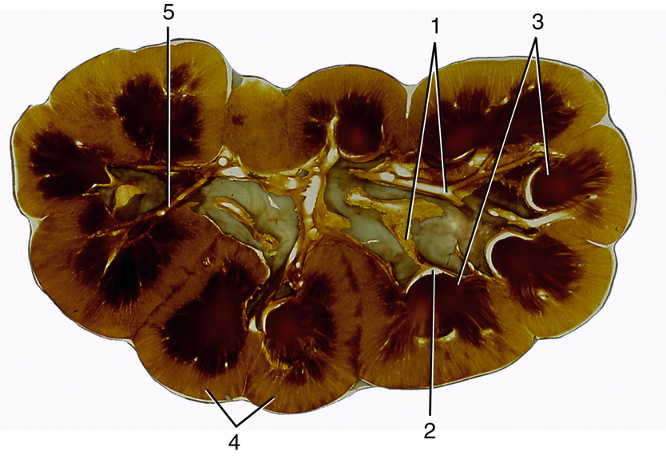

- Inside the kidney for each lobe, the outer layer is the cortex and the inner portion is the medulla (with renal papillae at the point of renal pyramids). (Fig. 28.27)

- Each lobe has a calyx (i.e., cup-like) that catches urine. All the calyces come together to form the renal pelvis that empties into a ureter. The ureters extend from each kidney to the caudal portion of the urinary bladder.

FIG. 28.27 Bovine kidney dissected to show its interior. 1, Principal branches of ureter; 2, calyx; 3, renal papillae; 4, renal cortex; 5, interlobular artery. TVA

- From the abdomen, structures of the pelvis may be found. The pelvic brim is the cranial edge of the pelvis/pubic region at the pelvic inlet.

- In females, the uterus (uterine horns, uterine body) and ovaries may be found in the caudal and lateral abdominal area.

- In males, the paired ductus deferens exit near the vaginal ring and deep inguinal ring in the caudal and ventral abdominal wall.

- The urinary bladder is the ventral-most organ in both males and females in the caudal abdomen near the pelvic inlet.

Bovine Abdominal Topography – note a large amount of abdominal organs are covered by the ribs, indicating these organs project into the thoracic space. In ruminants, the ruminoreticulum is so large that almost all other viscera are “pushed” to the right side. Day 1 bovine practitioners will need a good understanding of abdominal anatomy. You will use the location of “pings” or resonant areas to identify lesions or disorders in particular regions of the GI tract.

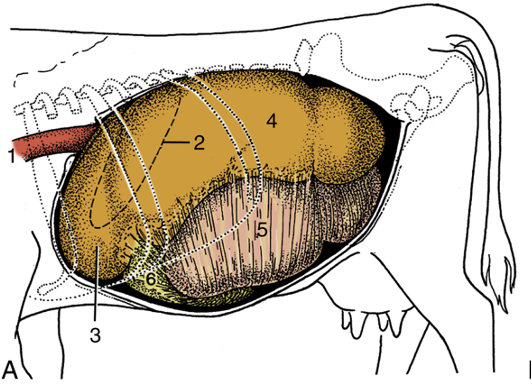

- Left side structures/organs in BOVINE (Fig. 28.4)

- The spleen is fused to the left side of the rumen and has a base (more dorsal) and apex (more ventral).

- The left kidney can not be palpated from the left side of the body as it is very dorsal and is pushed toward the midline due to the large rumen. The left kidney is connected to the spleen via the nephrosplenic ligament.

- The rumen takes up most of the left side of the abdominal cavity. The esophagus enters cranially into the rumen and reticulum region.

-

- The reticulum is the most cranial portion of the ruminant stomach. Ultrasound can be used to visualize reticular abscesses or lesions. The left flank (paralumbar fossa) can be used to access and explore the reticulum and rumen. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Rumenotomy)

- A small portion of the abomasum may be found on the left side, ventral to the cranial sac of the rumen.

FIG. 28.4 Topography of the bovine abdominal viscera. (A) Relationship of abdominal viscera to the left abdominal wall. 1, Esophagus; 2, outline of spleen; 3, reticulum; 4, dorsal sac of rumen; 5, ventral sac of rumen, covered by superficial layer of greater omentum; 6, fundus of abomasum, covered by superficial wall of greater omentum. TVA

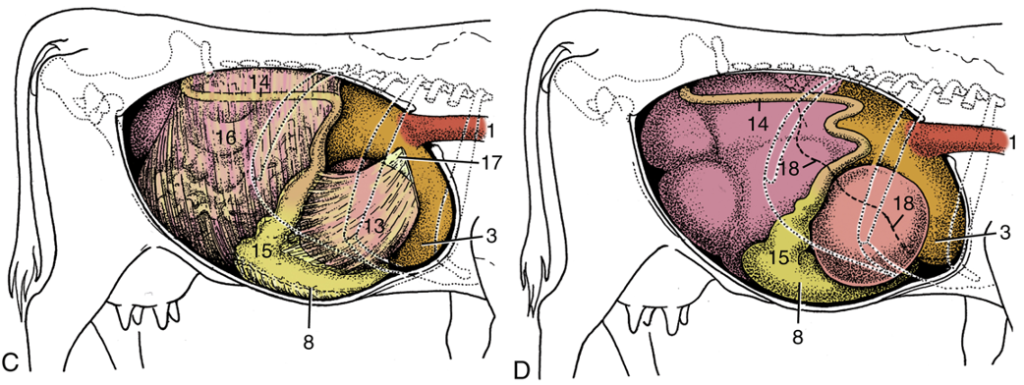

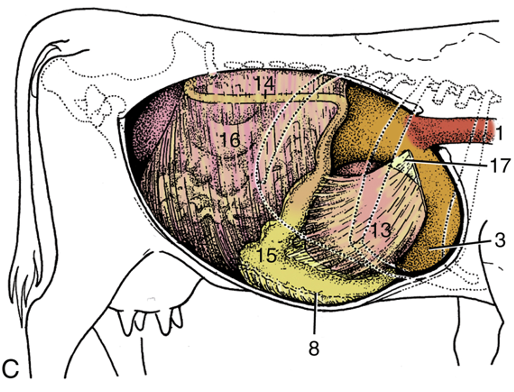

- Right side structures/organs in BOVINE (Fig. 28.4) (Supplemental Clinical LAS Bovine Abdominal Exploratory on Right)

- The liver is pushed almost entirely to the right side in BOVINE, with the right lobe and caudate lobe more dorsal and the left lobe more ventral in the abdomen.

-

- The omasum and abomasum are normally on the right side.

- Intestines (small – duodenum, ileum, jejunum and large – cecum, ascending colon and spiral colon) are found mainly within or tucked into the supraomental recess, and are deep to the mesentery on the right side. The descending duodenum is often in the middle of the right paralumbar fossa.

- The right and left kidneys may both be palpable from the right side of the body and are very dorsal, often near the caudal flexure of the duodenum.

FIG. 28.4 Topography of the bovine abdominal viscera. (C) Relationship of abdominal viscera to the right abdominal wall; the liver has been removed. (D) Position of the parts of the stomach seen from the right. 1, Esophagus; 3, reticulum; 8, body of abomasum; 13, omasum, covered by lesser omentum; 14, descending duodenum; 15, pyloric part of abomasum; 16, greater omentum covering the intestinal mass; 17, lesser omentum cut away from the liver; 18, position of caudoventral border of liver. TVA

Figure above – cross sectional view of the bovine abdomen. Labeled structures: 1-6, spleen; 9-12, pancreas; e, aorta; f, cranial mesenteric a.; g, celiac a.; h, caudal vena cava; i, splenic a. and v.; k, portal v.; l, duodenum; n, esophagus; o, lesser omentum; s, hepatic a. (Budras & Habel Bovine Anatomy)

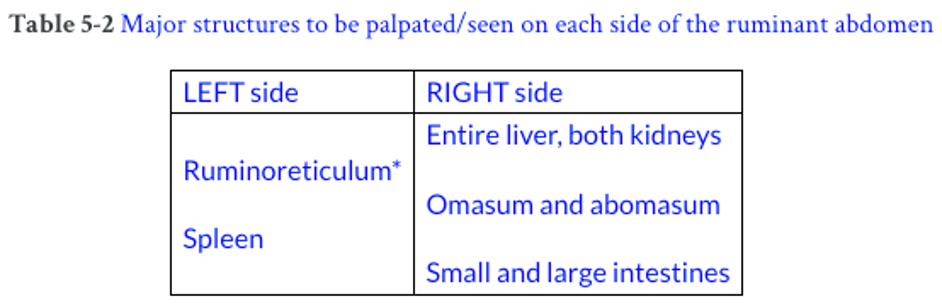

Table 5-2 (from LAA Dissection eBook) Major structures to be palpated/seen on each side of the ruminant abdomen.

*Note: The ruminoreticulum is so large that almost all other viscera are “pushed” to the right side. Even the left kidney is “pushed” to the right so that it hangs to the right of the dorsal sac near the midline.

Objective

A7.2 Summarize the regions of the gastrointestinal tract that are supplied by the celiac and cranial mesenteric arteries in bovine.

- The arterial pattern in large animals is similar to carnivores, where the main branches of the abdominal aorta include the: celiac, cranial mesenteric, and caudal mesenteric arteries.

- The celiac a. is unpaired and provides blood to viscera in the cranial abdominal cavity (i.e., foregut) via the:

- Splenic a. to the spleen and ruminant stomach.

- Hepatic a. to the liver, ruminant stomach, and part of the pancreas and duodenum.

- Left gastric a. to the ruminant stomach.

- The cranial mesenteric a. is unpaired (runs within the root of the mesentery) and provides blood to viscera in the middle abdominal cavity (i.e., midgut) via the:

- Jejunal aa. to the intestinal mass (found in much of the root of the mesentery and mesojejunum).

- Right colic aa. and colic brs. (branches of the ileocolic a.) to the ascending colon (spiral colon).

- Caudal mesenteric a. is unpaired and provides blood to viscera in the caudal abdominal cavity (i.e., hindgut) via the:

- Left colic a. to the descending/small colon.

- Cranial rectal a. to the upper rectum.

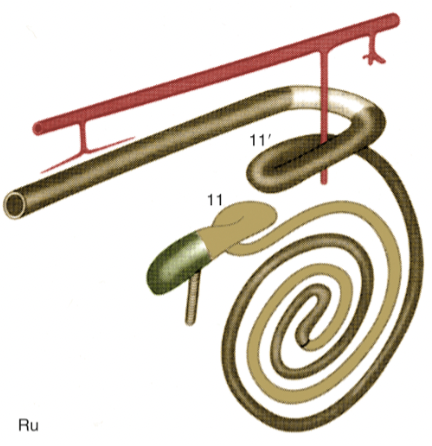

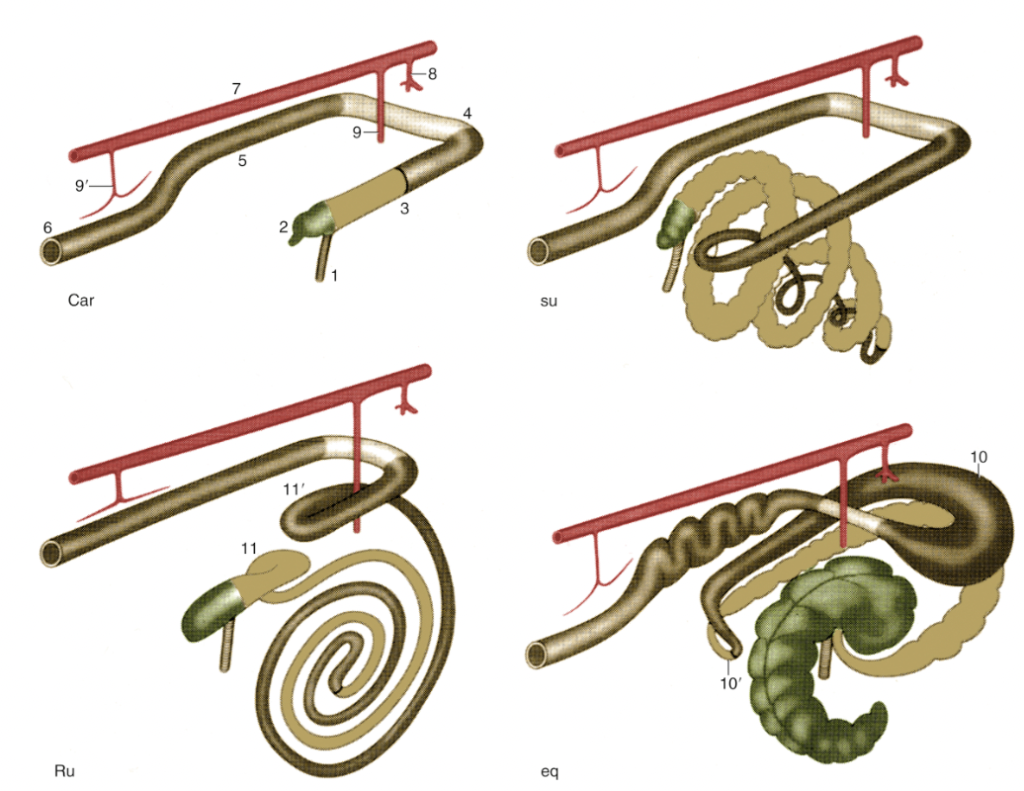

FIG. 3.45 Schematic drawing of the large intestine of ruminants (ru). Cranial is to the upper right, flow (each segment is a different color): ileum; cecum; ascending colon; transverse colon; descending colon; rectum and anus; The aorta is along the top with the celiac artery and cranial and caudal mesenteric arteries; 11 and 11′, proximal and distal loops of ascending colon. TVA

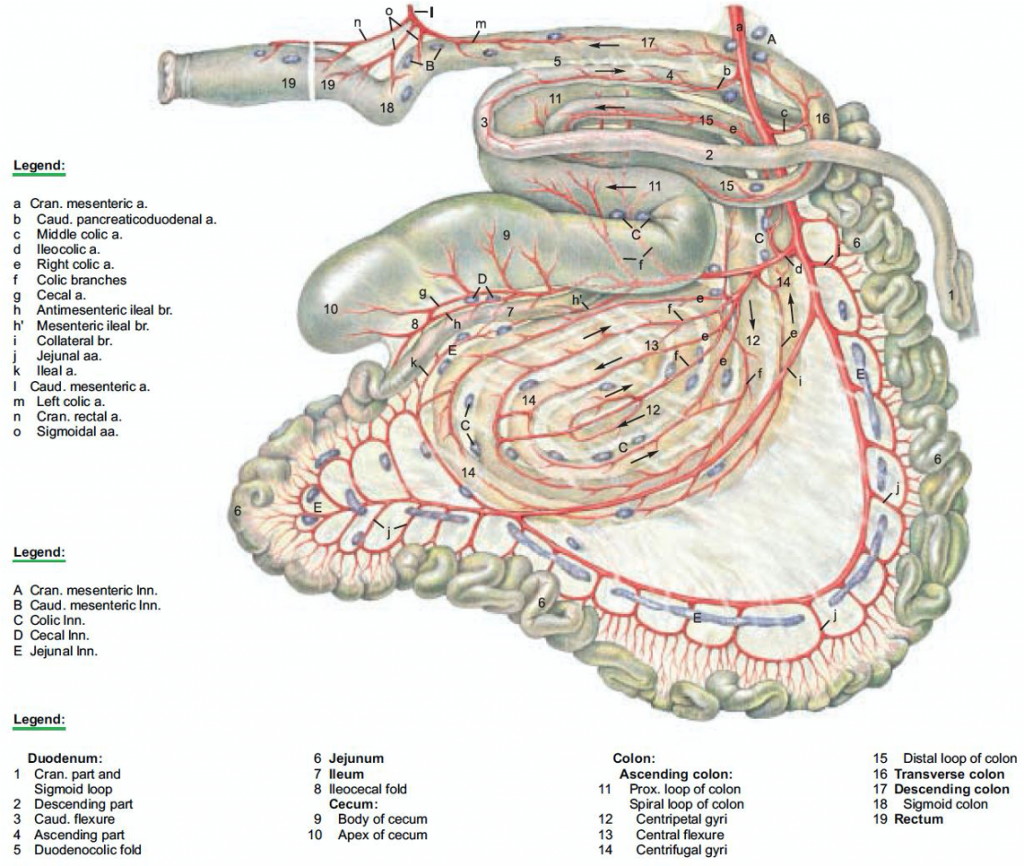

Figure above – bovine small and large intestines, arteries, and mesenteric lymph nodes (A-E). Labeled structures: a, cranial mesenteric a.; 1-5, duodenum; 6, jejunum; 7, ileum; 8, ileocecal fold; 9,10, cecum; 11-15, ascending colon; 12-14, spiral colon; 16, transverse colon; 17, descending colon. (Budras & Habel Bovine Anatomy)

Objective

A7.3 Identify and describe the anatomical features of the bovine/ruminant and camelid stomach (all chambers); summarize notable species differences.

Bovine Stomach (Figs. 11B-1,2,3) – There are dried, fresh, and preserved bovine stomach specimens available in the gross anatomy lab. Dried Ruminant Stomach (6:29)

- The rumen takes up most of the left side of the abdominal cavity, with the esophagus entering cranially into the rumen and reticulum region. Many structures of the ruminant stomach can be palpated by access via the flanks (paralumbar fossa).

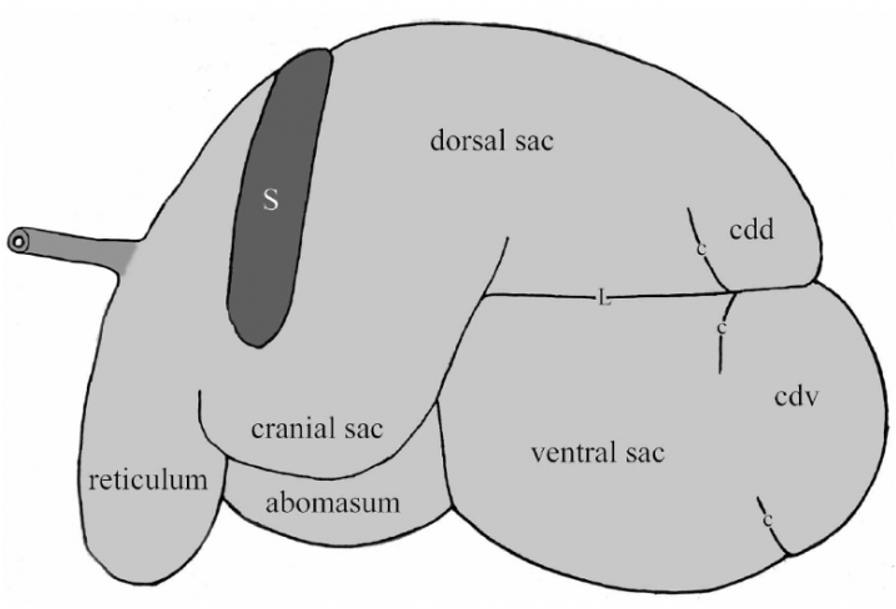

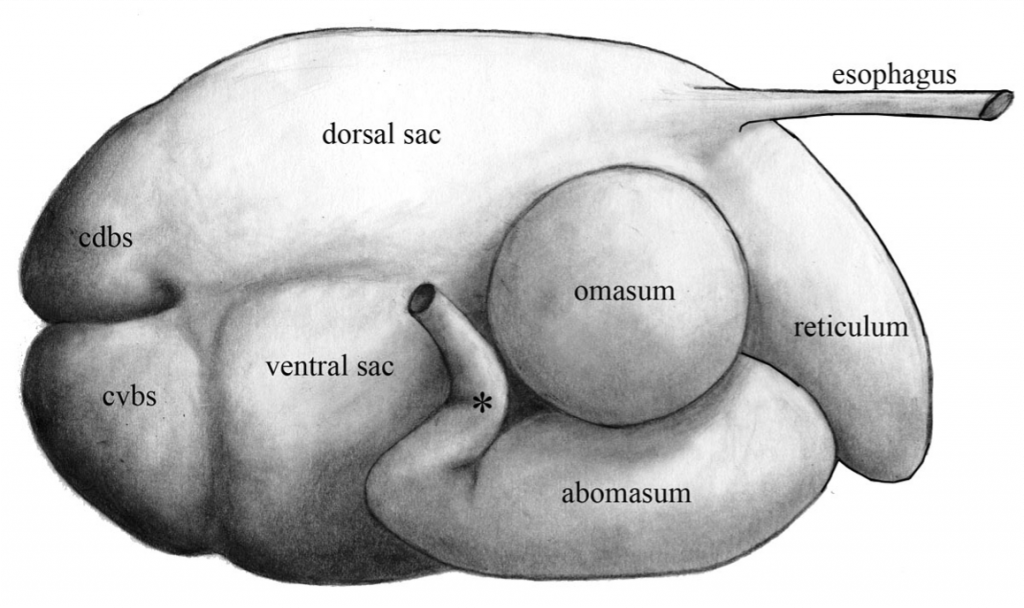

- The rumen has three sacs: dorsal, ventral, and cranial sacs.

- The grooves on the outside of the rumen delineate interior structures called pillars.

- The dorsal sac has a caudal dorsal blind sac, and there is a groove delineating it from the dorsal sac.

- The longitudinal grooves (on right and left sides) delineate the dorsal and ventral sacs. Internally, these grooves will be called right and left longitudinal pillars.

- The ventral sac has a caudal ventral blind sac, and there are grooves delineating it from the ventral sac. The ventral sac does extend to the right side of the ventral abdomen.

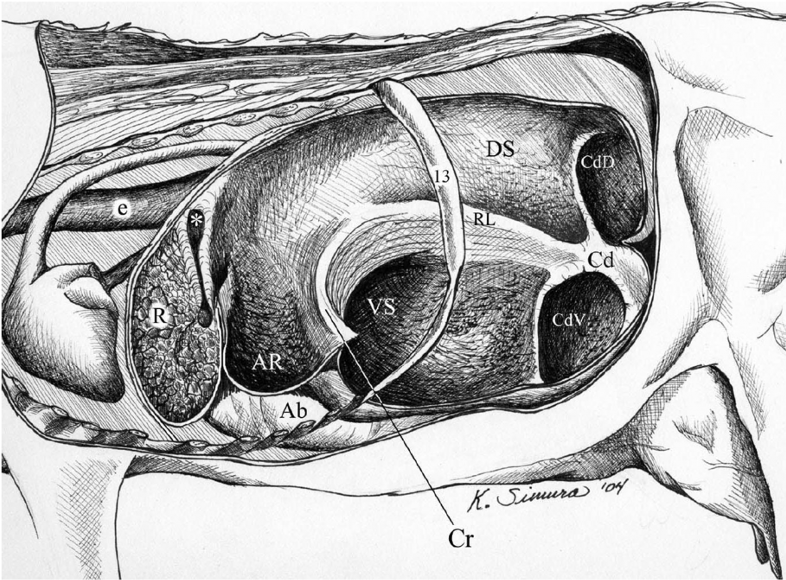

Fig. 11B-2 Bovine stomach, viewed from the left side. c, coronary groove (external, pillar internally) (dorsal and ventral); cdd, caudal dorsal blind sac; cdv, caudal ventral blind sac; L, left longitudinal groove; S, spleen. The esophagus (not labeled) is shown darker due to its striated muscle coat. (Also shown is the superficial layer of the omentum which attaches along the left longitudinal groove and covers the ventral sac, including the caudal ventral blind sac.) Labeled structures: dorsal sac, cranial sac, abomasum, reticulum.

Figure 11B-1 (Above) Bovine stomach, viewed from the right side. Cdbs, caudal dorsal blind sac; cvbs, caudal ventral blind sac; *, location of the pylorus. Labeled structures: esophagus, reticulum, dorsal and ventral sacs, omasum, abomasum.

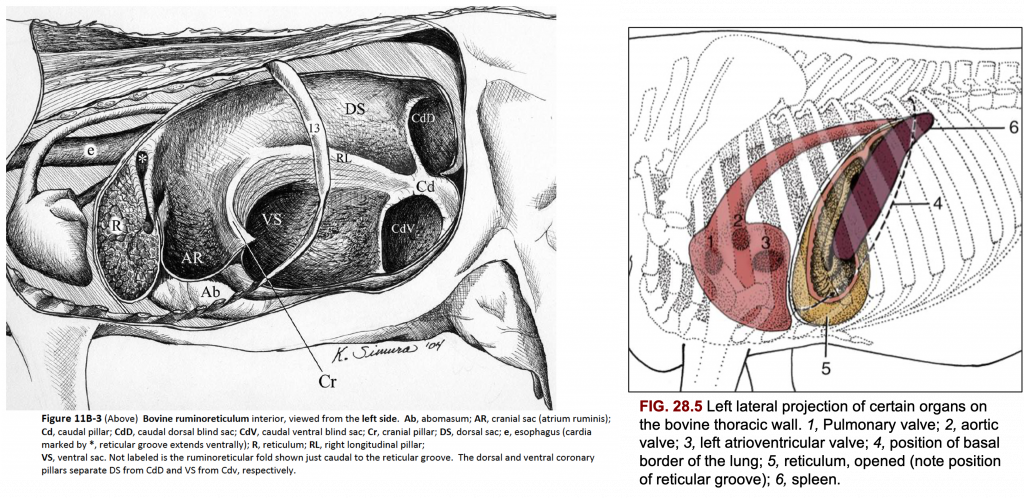

- Inside the rumen there are muscular pillars that function to partition and churn. The pillar names reflect the similarly named external structures. The ruminal wall has papillae of different sizes in different areas and allow for absorption. The pillars do not have papillae on them. (Fig. 11B-3)

- The right longitudinal pillar (called groove on the outside) partitions the right dorsal from the ventral sac. The left longitudinal pillar (called groove on the outside) partitions the left dorsal from the ventral sac.

- A large caudal pillar separates the caudal blind sacs, and a cranial pillar separates the dorsal and ventral sacs. These two pillars run horizontally. (Fig. 11B-3)

- The coronary pillars divide each caudal blind sac from the dorsal and ventral sacs. The coronary pillars are named dorsal coronary and ventral coronary in reference to the blind sac they create. The coronary pillars arise vertically from the caudal pillar. The sacs created by these pillars are the caudal dorsal blind sac and the caudal ventral blind sac.

- The cranial pillar separates the cranial sac from the dorsal and ventral sacs. The cranial sac is partitioned off from the reticulum via the ruminoreticular fold. The ruminoreticular orifice is at the boundary of the rumen and reticulum.

- The esophagus enters into the rumen and reticulum region at the region called the cardia. The cardia is at the top (or beginning) of the reticular groove. Food can either enter the rumen or reticulum, but ingesta usually flows from the cranial sac to the reticulum, and then flows out of the reticulum and into the omasum. (Fig. 11B-3) Per Dr. Malone: “rumen is fermentation, reticulum is sorting, omasum removes water and abomasum does the regular stomach stuff.”

- The reticular groove (aka esophageal groove) is a groove with two lips/edges on either side. When suckling calves take in milk, these ridges come together to form a tube to shunt the milk, bypassing the rumen and reticulum, and deliver milk directly into the omasum and abomasum. The end of the groove is called the reticulo-omasal orifice and is the opening into the omasum.

- The reticulum is the cranial-most region of the stomach and has reticular cells in a honeycomb pattern.

Figure 11B-3 Bovine ruminoreticulum interior, viewed from the left side. Ab, abomasum; AR, cranial sac (atrium ruminis); Cd, caudal pillar; CdD, caudal dorsal blind sac; CdV, caudal ventral blind sac; Cr, cranial pillar; DS, dorsal sac; e, esophagus (cardia marked by *, reticular groove extends ventrally); R, reticulum; RL, right longitudinal pillar; VS, ventral sac. Not labeled is the ruminoreticular fold shown just caudal to the reticular groove. The dorsal and ventral coronary pillars separate DS from CdD and VS from Cdv, respectively.

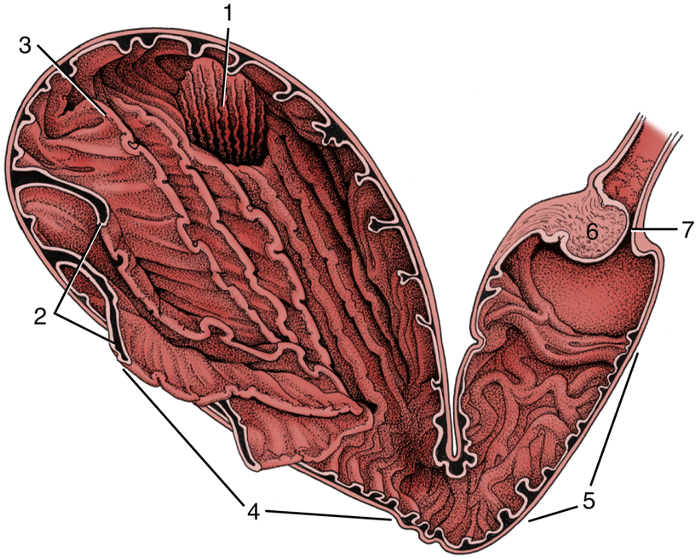

Figure above – Internal lining structures and patterns of the ruminant stomach, from left to right: two types of papillae (in rumen), reticular cells (honeycomb in reticulum), laminae (in omasum), folds (in abomasum). Modified from TVA

- The omasum is a softball shaped compartment on the right side of the ruminoreticulum and internally has compact laminae or flat sheets.

- The abomasum is similar to the traditional stomach we see in other animals and is also primarily on the right side of the ruminoreticulum. Similarly, it has a lesser and greater curvature, as well as a pylorus region. The lesser omentum and greater omentum attach to these lesser and greater curvatures, respectively.

- The abomasum is thrown into folds, similar to the rugae of the stomach and urinary bladder.

- BOVINE, like PORCINE, have a torus pyloricus near the pyloric sphincter (at entrance to the duodenum).

FIG. 28.22 Opened bovine abomasum as seen from behind, above, and slightly from the left. 1, Omasoabomasal opening through which the omasal laminae can be seen; 2, abomasal folds; 3, fundus; 4, body; 5, pyloric part; 6, torus pyloricus; 7, pyloric sphincter. TVA

- Connecting Mesenteries of the Bovine Stomach (Fig. 28.4, and below)

- The lesser omentum attaches along the lesser curvature of the abomasum and extends to the liver. The omasum is deep to the lesser omentum.

- The greater omentum attaches along the greater curvature of the abomasum and extends along the right boundary of the abdomen, up to the descending duodenum and its caudal flexure. The greater omentum encircles most of the GI tract creating a sling. (Fig. 28.4) However, the descending duodenum attaches to the dorsal body wall via the mesoduodenum and to the abomasum via lesser omentum allowing the duodenum to potentially twist if the abomasum is moved too far dorsally.

FIG. 28.4 Topography of the bovine abdominal viscera. (C) Relationship of abdominal viscera to the right abdominal wall; the liver has been removed. 1, Esophagus; 3, reticulum; 8, body of abomasum; 13, omasum, covered by lesser omentum; 14, descending duodenum; 15, pyloric part of abomasum; 16, greater omentum covering the intestinal mass; 17, lesser omentum cut away from the liver. TVA

-

- The greater omentum has superficial and deep leaves or layers that create a sling to house the GI tract. (Fig. 28.4, and below)

- The superficial layer attaches to the left longitudinal groove of the rumen, the greater curvature of the abomasum, and ventral edge of the descending duodenum.

- The deep layer attaches to the right longitudinal groove and the mesoduodenum.

- The sling is created by the deep layer of the greater omentum and allows the GI tract to sit within a space called the supraomental recess. The greater omentum encircles most of the GI tract creating a sling and making it difficult to see most GI structures. (Fig. 28.4) The sling can be pulled up caudodorsally to reveal and reposition the abomasum.

- The spiral colon and jejunum are suspended from the dorsal body wall by mesenteries, hence these intestines are suspended in the supraomental recess.

- The spiral colon is deep to the mesojejunum. The jejunum is at the ventral edge of the mesojejunum.

- The caudal fold is the caudal edge of the sling created by the greater omentum.

- The greater omentum has superficial and deep leaves or layers that create a sling to house the GI tract. (Fig. 28.4, and below)

-

-

- The omental bursa is formed between the superficial and deep layers of the greater omentum, which is a space outside of the supraomental recess (see image below).

-

Figure above – cross section of bovine abdomen showing the compartments formed by mesenteries. 1,1′, left and right longitudinal grooves; 2,2′, superficial layer of the greater omentum; 3,3′, deep layer of the greater omentum; 4, descending duodenum; 5, jejunum; 6, spiral colon; 7, mesojejunum; 8, spleen. Omental bursa – between superficial and deep layers of the greater omentum (light tan color); supraomental recess – within the two sides of the deep layer of the greater omentum, spiral colon and jejunum are in mesenteries hanging in this space (light green color).

Camelid Stomach (Fig. 11B-4 and images below) – There are camelid stomach specimens available in the gross anatomy lab. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Small ruminant and Camelid GI disorders)

Dried Camelid Stomach (4:12)

- Llamas and alpacas are commonly referred to collectively as South American Camelids (SAC) or new world CAMELIDS. Although they are often referred to as ruminants, they have large anatomic differences from true RUMINANTS (see Supplemental Table). The commonality with ruminants is gastric fermentation. They can thrive in environments where sheep would starve. Like ruminants, they are cud chewers, but they can spit.

- Camelid stomach has three compartments (first, second, third).

- C1: the largest; has cranial and caudal sacs, and regional sacculations (aka glandular saccules or cavities with glands) with internal and external indications of their presence; there are no papillae.

- Near the entrance of the esophagus into C1, there is a ventricular groove and one ventricular lip/fold (similar to the reticular groove of BOVINE). The groove leads from the esophagus towards C2.

- Inside C1, there is a transverse fold/pillar that separates the cranial and caudal sacs.

- Camelids do occasionally need C1-otomies for gastric indiscretion or impactions and can get gastric ulcers.

- C2: small, round; most of the wall has sacculations; small papillae are present.

- C3: long, tubular; distally, it has similar glandular features to the BOVINE abomasum, but no sacculations.

- C1: the largest; has cranial and caudal sacs, and regional sacculations (aka glandular saccules or cavities with glands) with internal and external indications of their presence; there are no papillae.

- The duodenum (D in images below) begins after the end of C3. The initial enlargement of the duodenum is known as the duodenal ampulla.

- CAMELIDS also have an ascending colon that is coiled into a spiral colon, similar to that of RUMINANTS, but it lacks proximal and distal loops.

- Camelids do form trichophytobezoars (hair + plant balls) and enteroliths (mineral concretion or calculus formed anywhere in the gastrointestinal system) that tend to lodge in the duodenum or spiral colon. The spiral colon in camelids is tightly wound and more prone to obstruction than in cattle.

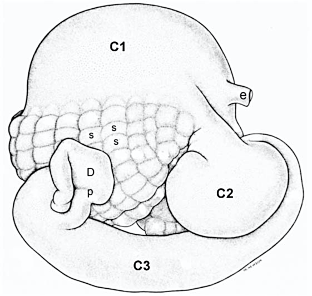

Figure 11B-4 (Above) Llama stomach, right side. e, esophagus; C1, C2, C3, stomach compartments; s, sacculations/glandular saccules of C1; p, pylorus; D, duodenum.

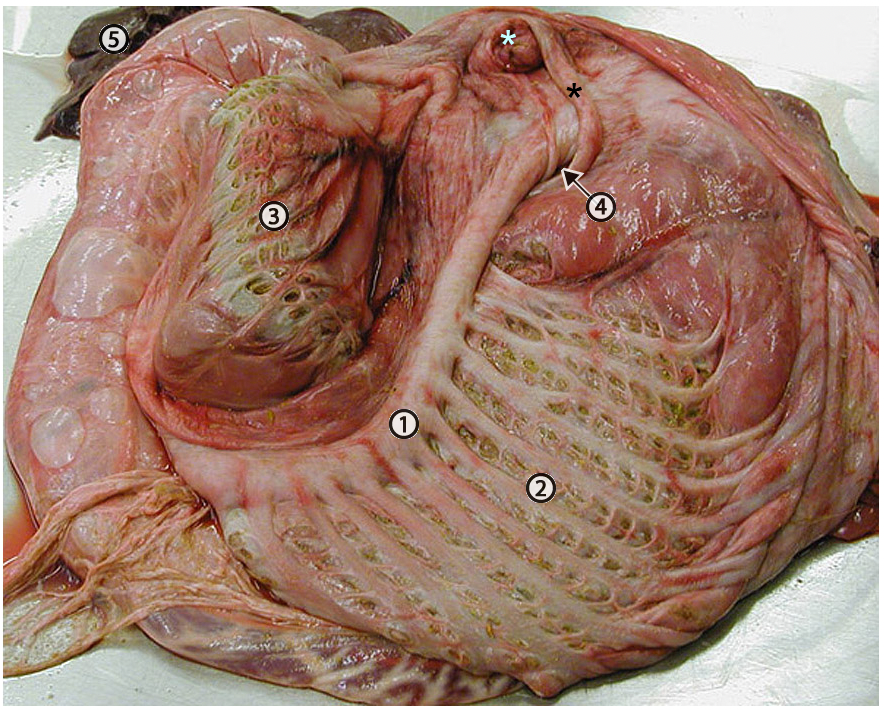

Figure above – Interior view of the first compartment of a llama stomach. A ventral transverse fold (1) separates the larger caudal part of (C1) from the smaller cranial part. The sacculations/glandular saccules are more numerous in the caudal part (2) than in the cranial part (3). The entry of the esophagus into C1 is marked by a light blue asterisk. A black asterisk marks the ventricular fold/lip which may guide some ingesta into the orifice of the second compartment (C2) (4). The liver (5) is visible. http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab14/Img14-25.html

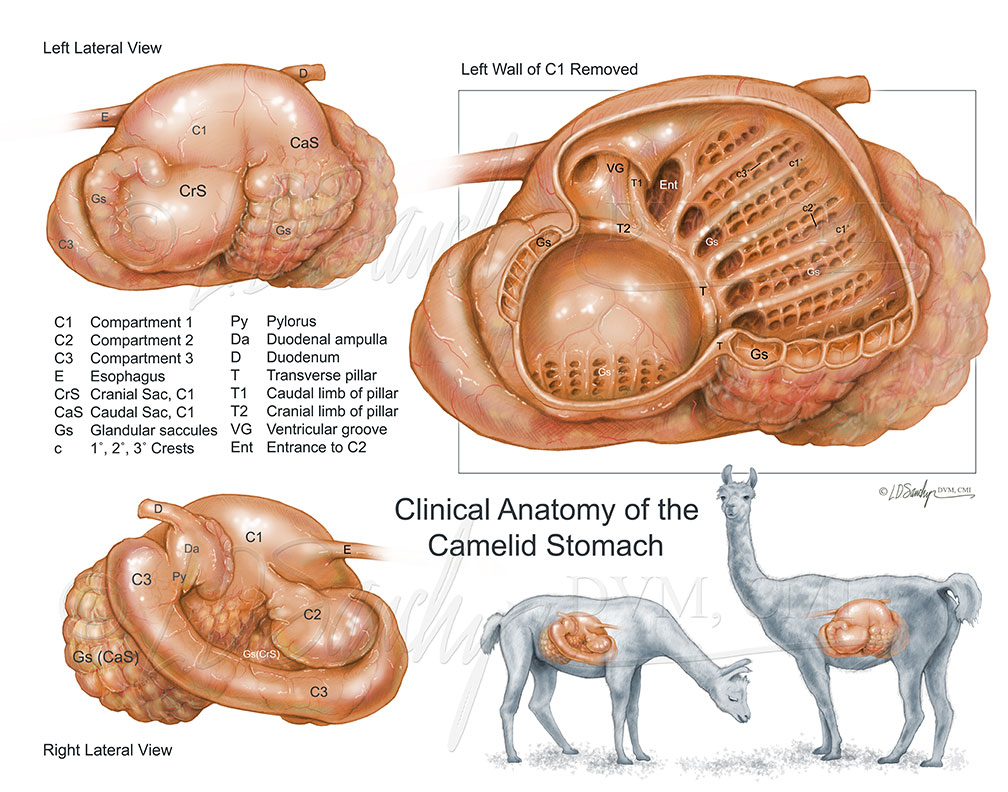

Figure above – Right and left lateral external views of the camelid stomach, and left lateral view with wall of C1 removed. C1; C2; C3; E, esophagus; CrS, cranial sac (C1); CaS, caudal sac (C1); Gs, glandular saccules/sacculations; c1-3′, crests; Py, pylorus; Da, duodenal ampulla; D, duodenum; T, transverse fold/pillar; T1, caudal limb of pillar; T2, cranial limb of pillar; VG, ventricular groove; Ent, entrance to C2.

Objective

A7.4 Identify and describe the anatomical features of the small and large intestines among ungulates (equine, bovine, porcine, camelid); describe the modifications of the ascending colon and summarize the normal flow of ingesta through the GI tract in the bovine.

PORCINE/SWINE/PIG (see previous application) = hindgut fermenter, omnivore (Fig. 3.45)

- The PIG GI tract has a relatively straight duodenum from the stomach to the more convoluted jejunum. The ileum straightens as it enters the ascending colon.

- The PIG has a prominent ileal papilla. The ileum enters into the cecum via this distinctive projection. The ileal papilla is well developed in the PIG but is not as prominent in other domestic animals.

- Pigs have a spiral colon with centripetal and centrifugal loops and a central flexure, but the centrifugal loops are narrower in diameter. There are no proximal and distal loops, and the spiral colon is in a cone configuration (bound together by mesentery) and is not flat.

EQUINE (see previous application) = hindgut fermenter, herbivore (Fig. 3.45)

- From the pylorus of the stomach, there are descending and ascending portions of the duodenum. There is a highly mobile jejunum, and the ileum enters the cecum at the ileocecal orifice/ileal orifice.

- Equine have a large cecum and extensive ascending colon. This allows for a large vat to break down grasses.

- The cecocolic orifice leads from the base of the cecum into a large diameter right ventral colon. The right ventral colon curves at the diaphragm via a ventral diaphragmatic flexure and continues as the left ventral colon.

- On the left side, the left ventral colon narrows and transitions to the left dorsal colon at the pelvic flexure. The left dorsal colon curves at the diaphragm via a dorsal diaphragmatic flexure and continues as the right dorsal colon. The colon narrows into the short transverse colon and then a longer and narrower descending (aka small) colon. The dorsal and ventral colon look like two horseshoes stacked on top of each other.

- The cecum and colon have bands and sacculations in equine.

- In equine, the cecum and ascending colon are the seat of the microbial fermentation that makes the cellulose constituents of the diet available, which is comparable to the chambers of the ruminant stomach. The large intestine is so voluminous that it is almost always encountered immediately when the abdomen is opened.

FIG. 3.45 Schematic drawing of the large intestine of the domestic mammals: carnivores (Car), the pig (su), ruminants (Ru), and the horse (eq). Cranial is to the upper right. 1, Ileum; 2, cecum; 3, ascending colon; 4, transverse colon; 5, descending colon; 6, rectum and anus; 7, aorta; 8, celiac artery; 9 and 9′, cranial and caudal mesenteric arteries; 10 and 10′, dorsal diaphragmatic and pelvic flexures of ascending colon; 11 and 11′, proximal and distal loops of ascending colon. TVA

BOVINE/RUMINANT = foregut fermenter, herbivore (Fig. 28.26) (additional real specimen labeled figures at vanat)

- An obvious modification in ruminants is the stomach, which has four compartments including a large rumen. From the rumen and reticulum, the tract continues with the omasum and abomasum. The abomasum leads to the duodenum, which continues into the jejunum and ileum.

- In the BOVINE there is a long straight cecum. The ileum enters at the ileal (ileocolic) orifice near the border of the cecum and ascending colon. Between the ileum and cecum there is a fold of mesentery called the ileocecal fold (it has a triangular shape).

- There is also a modification to the ascending colon called the spiral colon.

- The BOVINE spiral colon is held in a planar configuration (i.e., flattened spiral, keeping the ascending colon compact) and is fused to the mesocolon and the mesojejunum. This entire mass of intestines lies more dorsal in the supraomental recess.

- The spiral colon is fused to the deep surface of the mesojejunum and the mesenteric lymph nodes are found within the mesojejunum near the edge of the jejunum.

- CAMELIDS have a flat pattern like BOVINE, while PORCINE have a cone-shaped spiral colon. CAMELIDS and PORCINE do not have proximal or distal loops.

- There is a proximal loop before the spiral colon.

- The first half of the spiral has centripetal or “center seeking” coils/loops that continue to a central flexure. The central flexure is the midway point and corresponds to the central flexure of PIGS and CAMELIDS, and the pelvic flexure of the HORSE.

- The second half of the spiral has centrifugal or “center fleeing” coils/loops.

- The distal loop begins after the spiral and is the end of the ascending colon.

- The BOVINE spiral colon is held in a planar configuration (i.e., flattened spiral, keeping the ascending colon compact) and is fused to the mesocolon and the mesojejunum. This entire mass of intestines lies more dorsal in the supraomental recess.

- Distal to the ascending colon is the short transverse colon (which is cranial to the cranial mesenteric a.) and then the descending colon (aka small colon).

- Modifications of ascending colon in bovine: the ascending colon is the part of the large intestine that is elongated like other herbivores, while the spiral colon helps increase surface area and keeps the ascending colon compact in ruminants since most of their fermentation occurs in the ruminoreticulum. The first three chambers of the ruminant stomach are developed to cope with the complex carbohydrates that form such a large part of the normal diet of ruminants, and only the last chamber is comparable in structure and function to the simple stomach of most other species.

- Clinical Notes: bloat (free gas or frothy bloat due to obstructions or dietary changes) and distention of the abdomen are important to be aware of and to look for in ruminants. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Abdominal contour; Bovine GI Surgical disorders)

FIG. 28.26 Right lateral view of the bovine intestinal tract (schematic). 1, Pyloric part of abomasum; 2, duodenum; 3, jejunum; 4, ileum; 5, cecum; 6, ileocecal fold; 7–10, ascending colon: 7, proximal loop of ascending colon, 8, centripetal turns of spiral colon, 9, centrifugal turns of spiral colon, and 10, distal loop of ascending colon; 11, transverse colon; 12, descending colon; 13, rectum; 14, jejunal lymph nodes; 15, cranial mesenteric artery. TVA

Normal flow of ingesta through the bovine GI tract

esophagus > stomach (rumen > reticulum > omasum > abomasum) > duodenum (descending duodenum > caudal duodenal flexure/loop > ascending duodenum) > jejunum > ileum > ileocolic orifice > (cecum) > ascending colon (proximal loop > spiral colon [centripetal coils > central flexure > centrifugal coils] > distal loop) > transverse colon > descending/small colon > rectum > anus

Objective

A7.5 Define and describe the related anatomical structures associated with displaced abomasum and hardware disease.

Displaced Abomasum (Supplemental Clinical LAS Abomasal displacement)

- The cranial sac of the rumen does not rest on the floor of the abdominal cavity, hence there is room for the shifting of organs to occur. Specifically, the abomasum can shift from the right side of the abdomen to the left if there is free space. This is also common after calving, since GI structures and reproductive organs have shifted greatly.

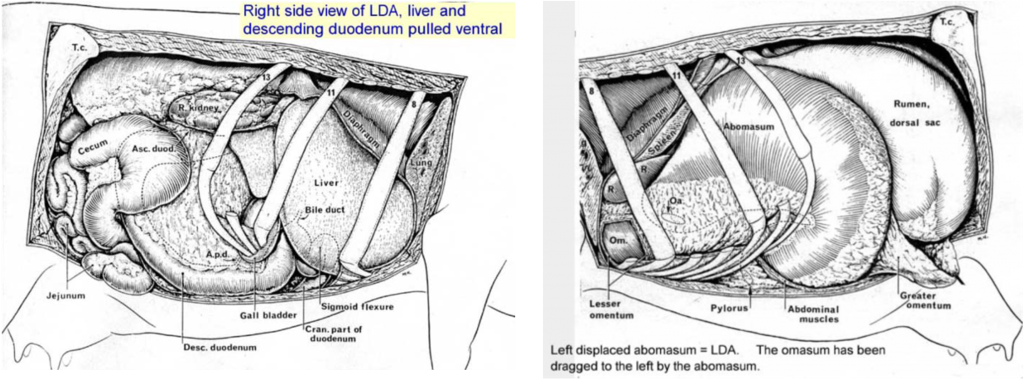

- Left displaced abomasum (LDA) occurs more often than right displaced abomasum. In LDA, the pyloric portion of the abomasum is most likely to shift from the right to the left side (see images below).

- Abomasal displacement puts tension on nearby organs and results in additional displacements. The abomasum can pull the omasum, liver, and descending duodenum with it ventrally and towards the left side of the abdomen. Remember, the omasum is connected to the abomasum, the liver is attached to the lesser omentum of the abomasum, and the descending duodenum is attached to the greater omentum and pylorus of the abomasum.

- In the new left shifted position the abomasum doesn’t drain well, microbes produce gases that can’t escape, and the abomasum becomes dilated.

- Surgeons will attempt to tack the abomasum in place (via the right flank) using the omentum adjacent to the pylorus and its antrum.

- Right displaced abomasum (RDA) occurs less often than LDA and may be associated with torsion or twisting of the abomasum.

Figure above – right (on left) and left (on right) sided view of bovine abdominal organs with a left displaced abomasum (LDA). Right view: note liver and descending duodenum are pulled ventrally. Left view: the omasum has been pulled with the abomasum to the left side, covering the cranial rumen.

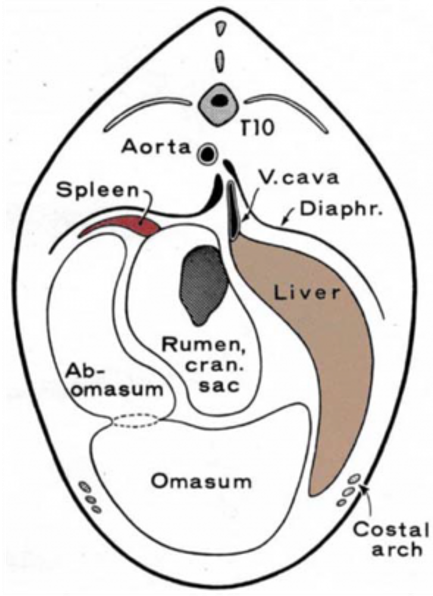

Figure above – cross section view of bovine abdomen withe left displaced abomasum (LDA). Note liver pulled dorsally on the right, omasum situated ventrally, and the abomasum on the left, with the rumen in the center.

Hardware Disease (Supplemental Clinical LAS Hardware disease)

- The reticulum has hexagonal reticular cells (giving it a honeycomb appearance) covered with small papillae. These structures help delay the transit of ingesta and thereby increase time for absorption of volatile fatty acids.

- The reticulum is the most cranial portion of the ruminant stomach and is pushed up against the diaphragm, placing it relatively close to the heart.

- Hardware disease or traumatic reticuloperitonitis can be with or without pericarditis.

- Cows eat all sorts of stuff. Any foreign bodies usually end up in the reticulum. This includes nails, wire, ropes, etc.

- Sharp objects can be pushed through the reticular wall, due to the churning in the rumen and reticulum. A hole in the reticulum can leak ingesta and cause peritonitis and abscesses. Further migration can occur, penetrating through the diaphragm, and then the pericardial sac of heart. This can lead to pericarditis and pleuritis.

- To protect cows a magnet is passed into the reticulum prophylactically, or after known ingestion to bind up sharp metallic objects and prevent migration through the reticular wall.

Figure 11B-3 Bovine ruminoreticulum interior, viewed from the left side. Ab, abomasum; AR, cranial sac (atrium ruminis); Cd, caudal pillar; CdD, caudal dorsal blind sac; CdV, caudal ventral blind sac; Cr, cranial pillar; DS, dorsal sac; e, esophagus (cardia marked by *, reticular groove extends ventrally); R, reticulum; RL, right longitudinal pillar; VS, ventral sac. Not labeled is the ruminoreticular fold shown just caudal to the reticular groove. The dorsal and ventral coronary pillars separate DS from CdD and VS from Cdv, respectively.

FIG. 28.5 Left lateral projection of certain organs on the bovine thoracic wall. 1, Pulmonary valve; 2, aortic valve; 3, left atrioventricular valve; 4, position of basal border of the lung; 5, reticulum, opened (note position of reticular groove); 6, spleen. TVA