8 Pelvis and Perineum

Revised Spring 2024 by T. Clark

Additional Resources for this Chapter:

- Related Supplemental Large Animal Surgery links: LAS Nerve damage; LAS Rectovaginal lacerations; LAS Perineal anatomy; LAS Perineal analgesia

- Veterinary Gross Anatomy Ungulate Dissection (Pelvis Labs 15-17)

- Associated Video Links:

- Equine & Bovine Pelvis (many repeated terms from Pelvic Limb) (2 videos, 7:50, 4:53)

Associated Clinician topics: dystocia, pelvic dimensions – (The most relevant objectives: A8.1, A8.2, A9.4)

Objective

A8.1 Identify and describe the structures forming the pelvis, pelvic inlet, and pelvic outlet; describe the clinical significance of these regions with normal parturition and dystocia.

Pelvis (Figures 4-3, 4-6, and 4-7) (Most of these terms were also covered in Application 3 Pelvic Limb)

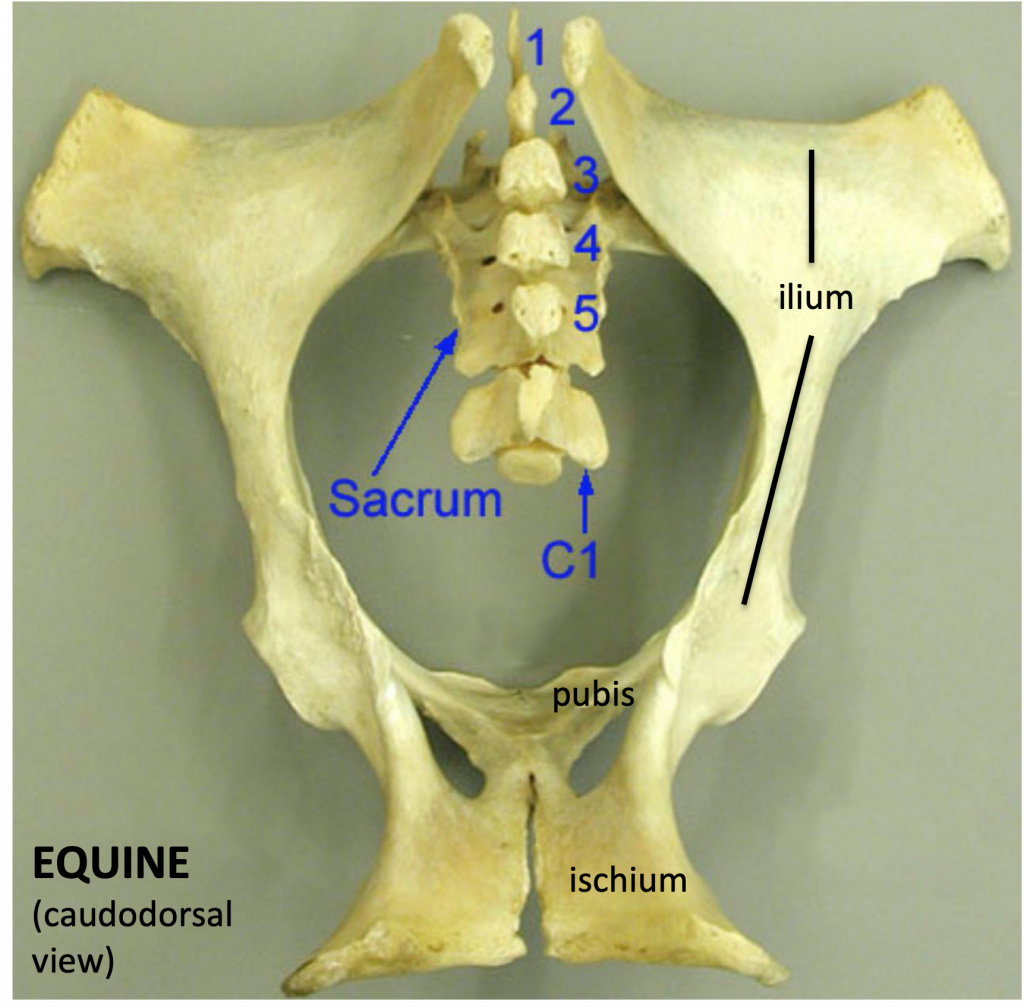

Figure above – caudodorsal view of an equine bony pelvis. Labeled structures: 5 sacral vertebrae (sacrum), C1 (first caudal/coccygeal vertebra), body and wing of ilium, pubis, ischium.

- The pelvis is composed of the sacrum and two hip bones (called the os coxae) that unite ventrally at the pelvic symphysis.

- Sacrum: the sacrum consists of 5 fused sacral vertebrae.

- The sacroiliac joint(s) are formed by the overlapping of the wing of the sacrum and the wing of the ilium.

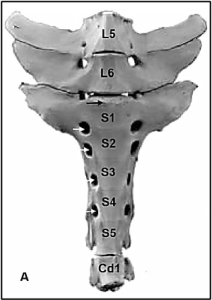

- The sacrum also has (dorsal and ventral) sacral foramina. Separate dorsal and ventral sacral foramina exist for respective branches of the sacral spinal nerves. (Fig. below)

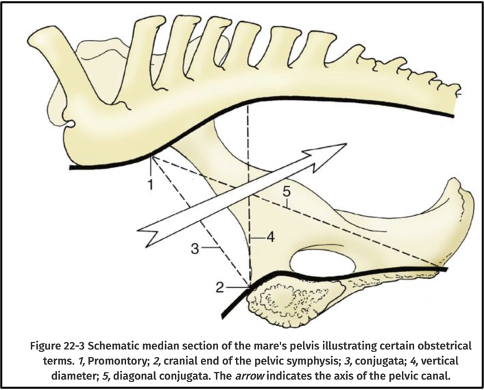

- Ventrally, the body of the first sacral vertebra forms the sacral promontory, the cranial edge of this vertebra. It forms part of the dorsal boundary of the bony pelvic inlet. (Fig. 22.3 and below)

- The 1st caudal/coccygeal vertebra attaches to the caudal aspect of the sacrum and is also included in the bony pelvis.

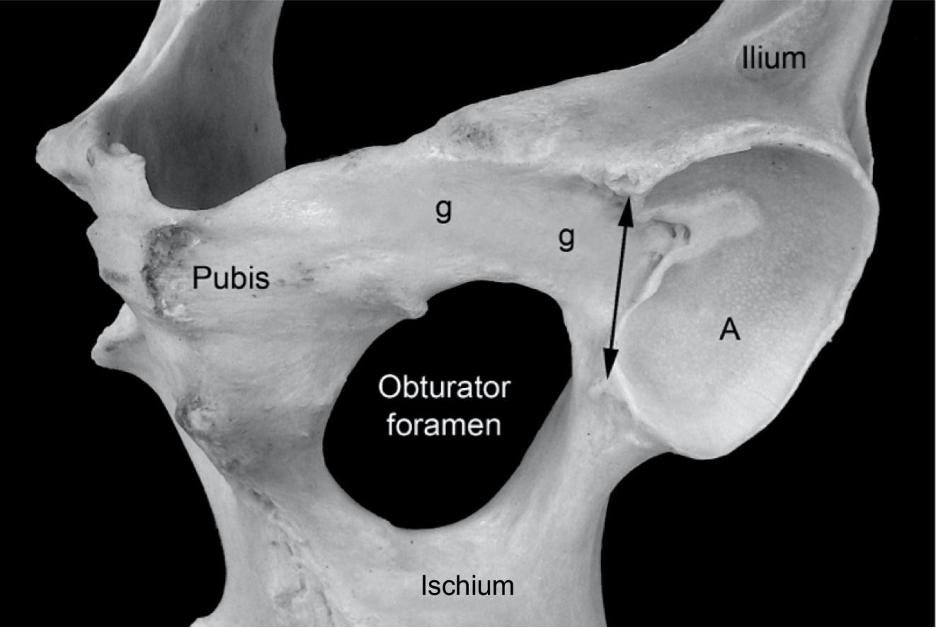

- Each os coxae is formed by the ilium, ischium, pubis, and a small acetabular bone. The acetabulum creates the socket of the hip and is formed by the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis. There is an acetabular notch ventrally. (Fig. 4-6)

- Sacrum: the sacrum consists of 5 fused sacral vertebrae.

Figure 4-6 (Above) Equine left acetabulum, ventral lateral view. A, Articular surface of the acetabulum; g, shallow groove for the accessory ligament of the femoral head; double headed arrow, acetabular notch and the location of the transverse acetabular ligament.

Figure above – bovine sacrum, ventral view. White arrows, ventral sacral foramina; black arrow, sacral promontory.

-

- The pubis is the cranioventral portion of the pelvis. The cranial edge of the pubis forms the pelvic brim, and is the attachment site of the prepubic tendon (i.e., tendinous insertion of the rectus abdominis mm.).

- The obturator foramen (one on each side), formed by the ischium and pubis, is a large foramen that is covered by obturator mm. (including the internal and external obturator mm.). The obturator n. (and artery in equine) runs through the cranial portion of this foramen. (Fig. 4-6)

- The pubis is the cranioventral portion of the pelvis. The cranial edge of the pubis forms the pelvic brim, and is the attachment site of the prepubic tendon (i.e., tendinous insertion of the rectus abdominis mm.).

-

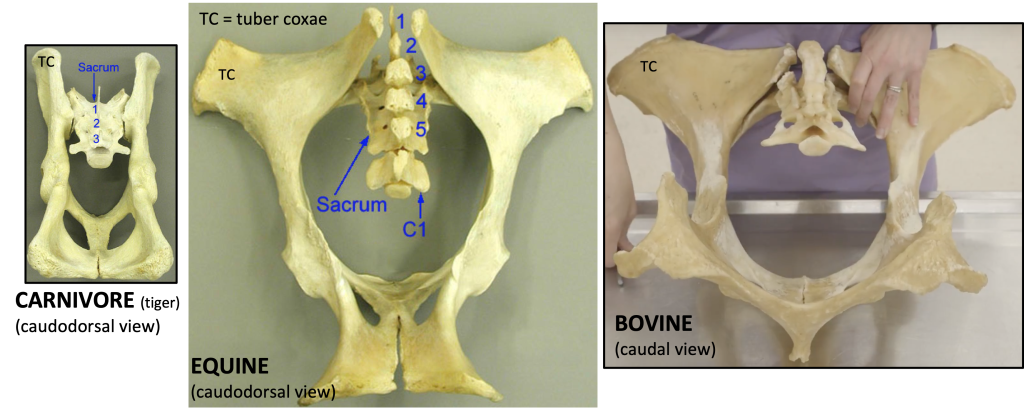

- The ilium forms the lateral portion of the pelvis and has an iliac body and wing. The medial projection of the wing (towards the sacrum) is the tuber sacrale, and the lateral projection is the tuber coxae (Fig. 4-3).

- In the CALF, the wing of the ilium is oriented vertically, similar to the DOG/CARNIVORES (i.e., tuber sacrale dorsal to tuber coxae). However, in the adult RUMINANT and EQUINE the tubera coxae are displaced laterally. The wide spread of the tubera coxae (plural of tuber coxae) parallels the development of voluminous abdominal organs and an expansive abdominal cavity in herbivores. In particular, the outward movement of the internal abdominal oblique mm. results in the lateral displacement of this bony attachment site.

- The ilium forms the lateral portion of the pelvis and has an iliac body and wing. The medial projection of the wing (towards the sacrum) is the tuber sacrale, and the lateral projection is the tuber coxae (Fig. 4-3).

Figure above – caudodorsal or caudal views of (from left to right): adult carnivore (tiger), adult equine, and adult bovine bony pelvis. Labeled structures: TC = tuber coxae, sacrum, C1 (1st caudal vertebra), sacral vertebrae (1-5).

-

-

- Clinical Note: The tubera coxae of CATTLE are called “hook bones” and a clamp-like device called a hook hoist is often attached here to lift recumbent cattle that are unable to stand. The wide spread of the tubera coxae make them high risk areas for fracture, especially in the case of older animals.

- The tubera coxae of the HORSE are difficult to palpate in the live animal because the pelvis and rump is more muscular than that of RUMINANTS.

-

-

- The ischium is the most caudoventral portion of the pelvis and has a projection called the tuber ischii. Between the ilium and the ischium is the ischiatic spine.

- The right and left ischia unite to form an ischial arch along their caudal border. This arch can be especially deep in CATTLE.

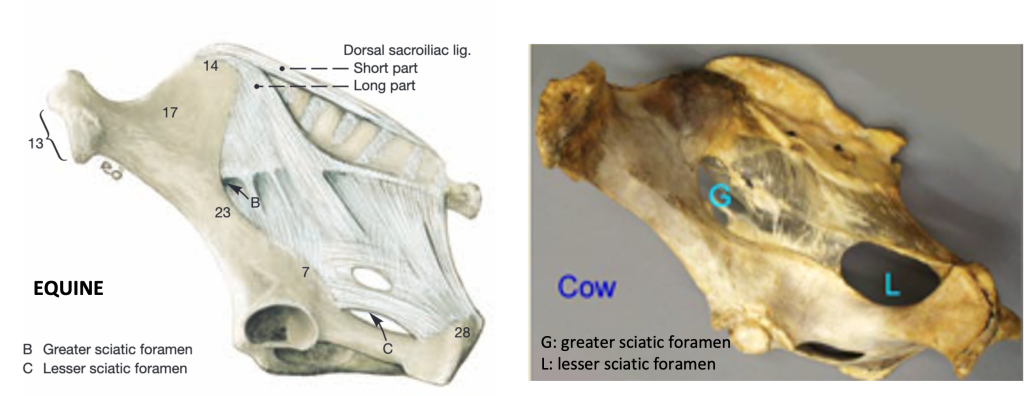

- The lateral union of ischium and ilium form a dorsal elevation called the ischiatic spine; greater and lesser sciatic notches (that form foramina) occur cranial and caudal to this spine, respectively (Fig. 4-3).

- Clinical Note: the tubera ischii (known as ‘pin bones’ in CATTLE) form the widest point of the pelvic outlet. Dairy cows are judged on, and selected for, wide spread pin bones. (In the HORSE, the tubera ischii are covered by hamstring muscles.)

- The head of the femur, which articulates with the acetabulum, is found medially, while on the lateral side there is the greater trochanter with cranial and caudal parts. (Figs. 4-3 and below)

- The ischium is the most caudoventral portion of the pelvis and has a projection called the tuber ischii. Between the ilium and the ischium is the ischiatic spine.

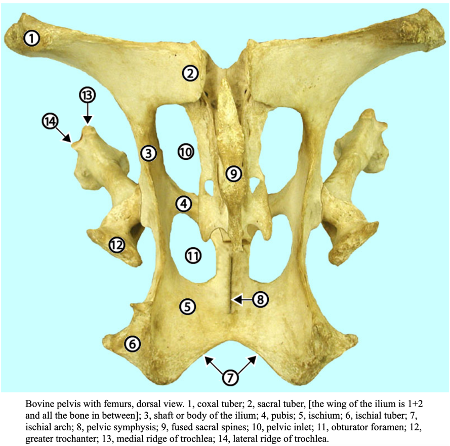

Fig. (above) Bovine pelvis with femurs, dorsal view. 1, tuber coxae; 2, tuber sacrale, [the wing of the ilium is 1+2 and all the bone in between]; 3, shaft or body of the ilium; 4, pubis; 5, ischium; 6, tuber ischii; 7, ischial arch; 8, pelvic symphysis; 9, fused sacral spines; 10, pelvic inlet; 11, obturator foramen; 12, greater trochanter; 13, medial ridge of trochlea; 14, lateral ridge of trochlea. (http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab05/Img5-16.html)

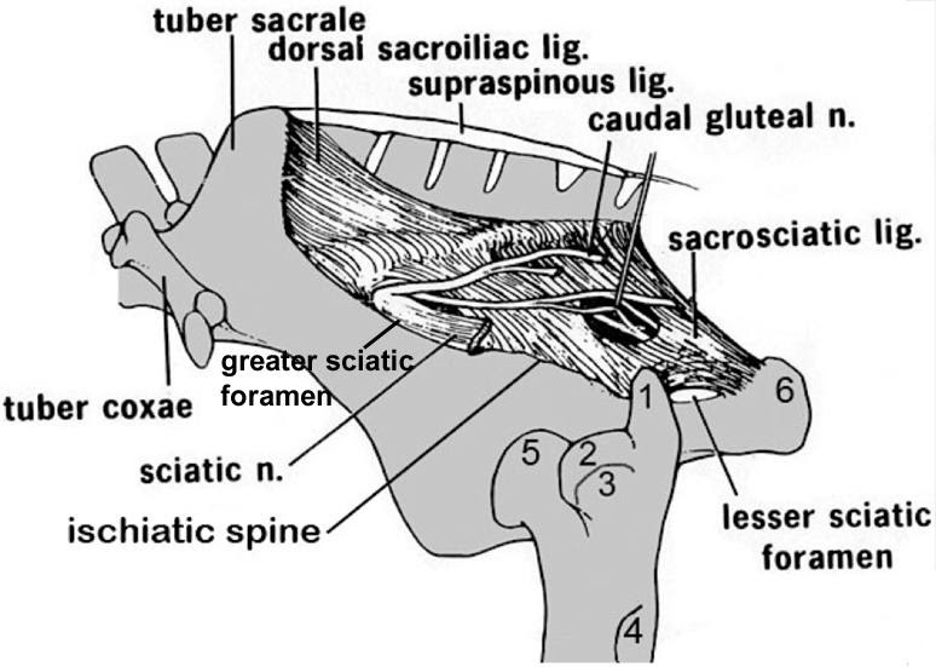

Figure 4-3 Equine pelvis and proximal femur, lateral view. 1, Caudal (middle gluteal) cusp of the greater trochanter; 2, cranial (deep gluteal) cusp of the greater trochanter; 3, facet for insertion of accessory gluteal; 4, third trochanter (superficial gluteal); 5, head of femur (in the acetabulum); 6, tuber ischii. Labeled structures: tuber sacrale, tuber coxae, ischiatic spine, greater and lesser sciatic foramen, sacrosciatic ligament, sciatic n.

Pelvic Inlet and Outlet

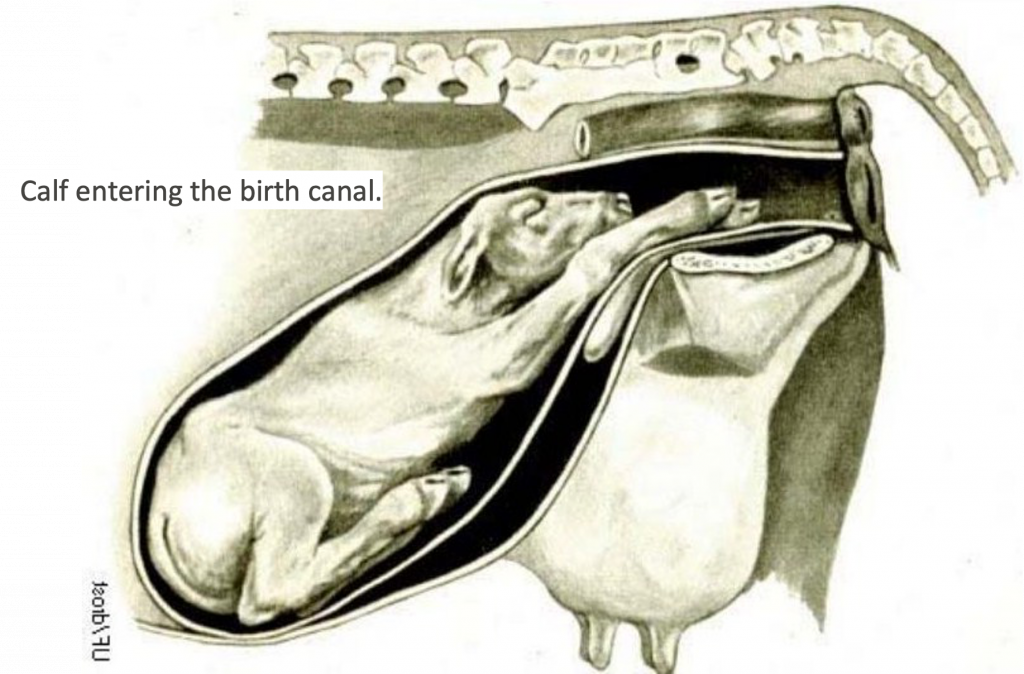

- The pelvic canal, or birth canal, is where the fetus passes to exit the female reproductive tract. The pelvic inlet and outlet form the beginning and end of the birth canal, respectively. (Figs. 22.3, 29.3, 29.1)

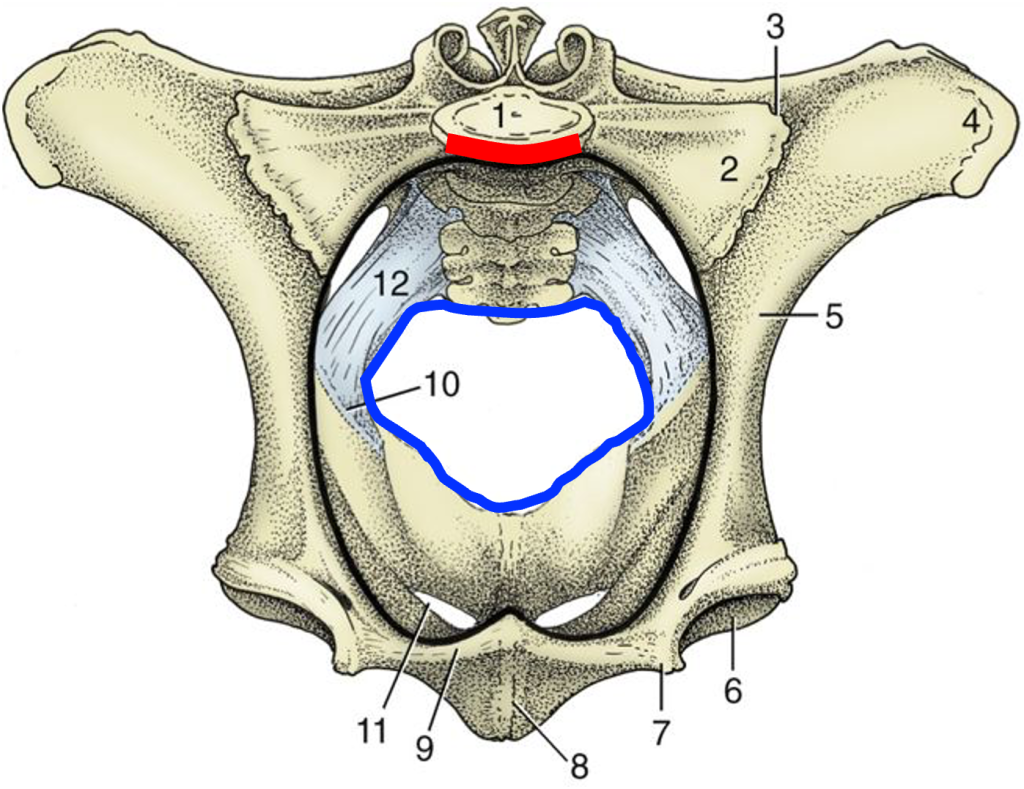

- The pelvic inlet is the ‘opening’ at the cranial aspect of the pelvis, formed by pelvic bones and the sacrum. This includes the wings of the sacrum, the craniomedial border of the ilium, and the pelvic brim of the pubis.

- The pelvic inlet is the size limiting feature of the birth canal as it is bounded by bones and is not expandable. Therefore, the widest part of a fetus would need to be smaller than the pelvic inlet to pass through the birth canal successfully. Females of different species (e.g., mare, cow) tend to have larger diameter pelvic inlets than males.

- The pelvic outlet is the ‘opening’ at the caudal aspect of the pelvis formed by the caudal vertebrae, sacrosciatic ligament (sacrotuberous part) and the ischial arch (the arch between the tuber ischii). Note that the ischial arch is especially deep in cattle. This means that the pelvic outlet has a ligamentous border and has some ability to stretch.

- The pelvic inlet is the ‘opening’ at the cranial aspect of the pelvis, formed by pelvic bones and the sacrum. This includes the wings of the sacrum, the craniomedial border of the ilium, and the pelvic brim of the pubis.

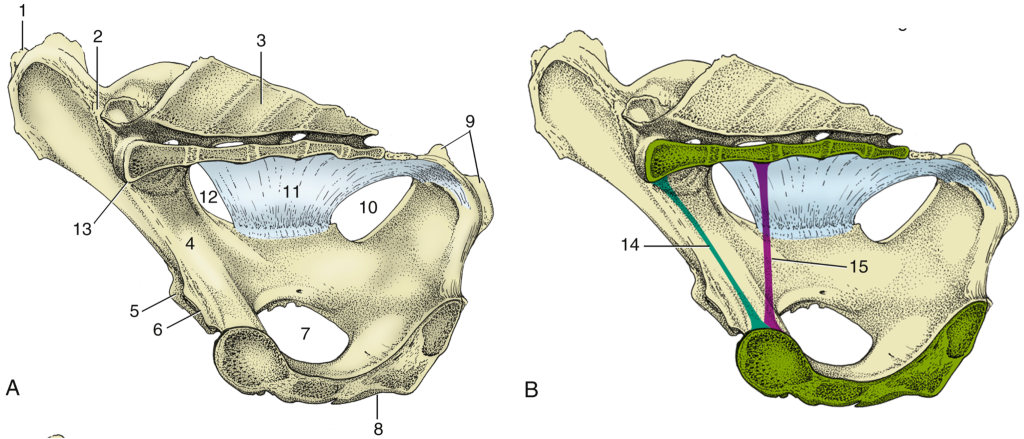

Fig. 29.3 Cranial view of the bony pelvis of a cow. The rim of the pelvic inlet (black line) and edge of the pelvic outlet (blue line) is indicated. 1, Body of first sacral vertebra, sacral promontory (red line); 2, wing of sacrum; 3, sacroiliac joint; 4, tuber coxae; 5, shaft of ilium; 6, acetabulum; 7, iliopubic eminence; 8, symphysis; 9, pecten pubis; 10, ischiatic spine; 11, obturator foramen; 12, sacrosciatic ligament. TVA

FIG. 22.3 Schematic median section of the mare’s pelvis illustrating certain obstetric terms. 1, sacral promontory; 2, cranial end of the pelvic symphysis; 3, conjugata; 4, vertical diameter; 5, diagonal conjugata. The arrow indicates the axis of the pelvic canal. TVA

Figure above – calf entering the birth canal.

- The sacrosciatic ligament is a broad ligament spanning from the sacrum to the ilium and ischium and is slightly different in BOVINE and EQUINE. The caudal thickened edge of this ligament is homologous to the sacrotuberous ligament of the DOG. The sacrosciatic ligament forms part of the boundary of the pelvic outlet. (Fig. 4-3 and below)

- The greater sciatic foramen is formed by the bony greater sciatic notch (of the ilium) and the sacrosciatic ligament. The sciatic n. and the cranial gluteal a. exit the pelvis from this foramen in BOVINE and EQUINE.

- The lesser sciatic foramen is formed by the bony lesser sciatic notch (of the ischium) and the sacrosciatic ligament. The caudal gluteal a. exits the pelvis from this foramen in BOVINE. The tendon of the internal obturator m. exits from this foramen in EQUINE.

- In EQUINE, the caudal gluteal a. pierces the sacrosciatic ligament dorsal to the lesser sciatic foramen.

-

- Clinical Note: when a cow is in heat or close to parturition, the tail head raises up, and components of the sacrosciatic ligament relax.

Figure above – caudal view of bovine rump and tail head. Indications of impending parturition in the cow include relaxation of the sacrosciatic ligament (yellow arrow). Also note, the ischiorectal fossae (depressions between tuber ischii and rectum) on either side of the tail. TVA

Figure above – equine (left) and bovine (right) lateral view of pelvic bone and sacrosciatic ligament. Labeled structures: B or G, greater sciatic foramen; C or L, lesser sciatic foramen.

Inguinal Structures

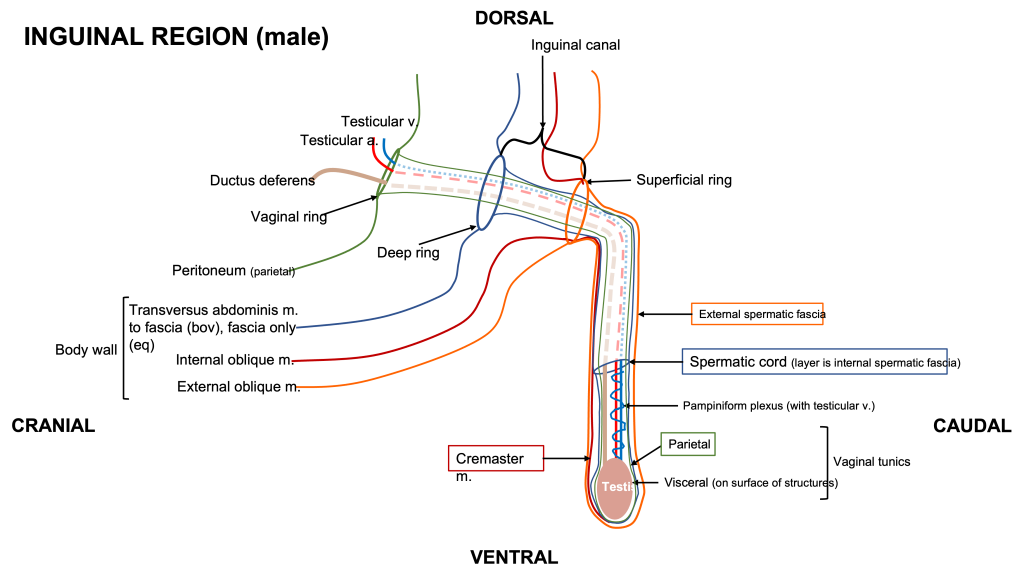

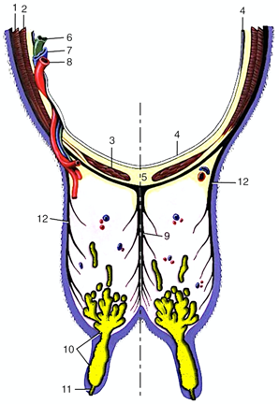

- The inguinal canal is an opening in the caudal part of the abdominal wall, through which the testis travels in its descent into the scrotum. There is a left and a right inguinal canal. (Figs. 21.3,4 and below)

- The entrance to the inguinal canal is the deep inguinal ring which is between the free caudal edge of the internal abdominal oblique m. and the caudal edge of the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m. (the inguinal ligament) on the deep surface of the abdominal wall.

- The exit of the inguinal canal is the superficial inguinal ring which is a slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique m. on the outer surface of the abdominal wall.

- The transversus abdominis m. is the deepest abdominal muscle layer and the rectus abdominis mm. are paired and found running cranial to caudal near the ventral midline (all having some form of attachment near the pelvic brim).

- The inguinal canal of CATTLE resembles that of the HORSE. Inguinal hernias are infrequent in CATTLE but common in male SHEEP. (TVA)

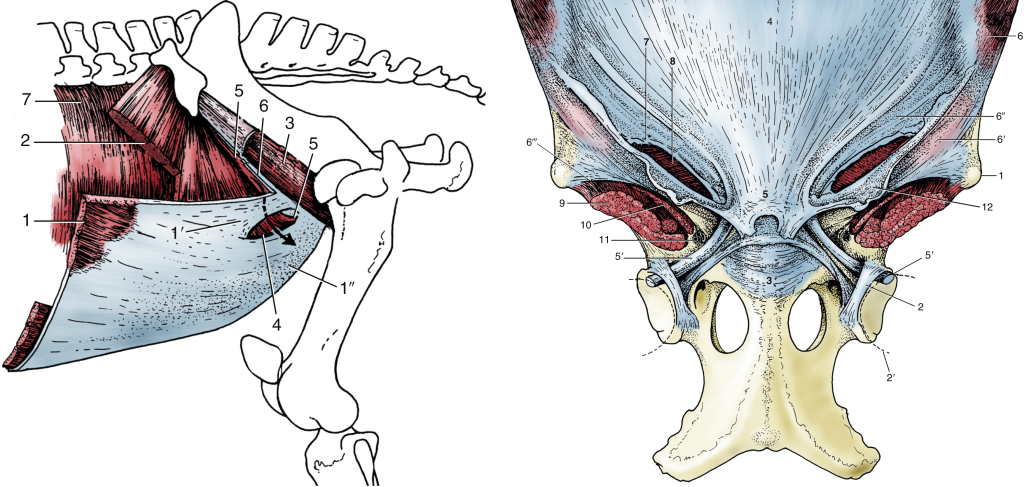

FIG. 21.4 The muscles of the equine inguinal region. The arrow passes through the inguinal canal. 1, External abdominal oblique; 1′ and 1″, pelvic and abdominal tendons of external oblique aponeurosis, respectively; 2, internal abdominal oblique; 3, iliopsoas partly enclosed by iliac fascia; 4, superficial inguinal ring; 5, cranial border of deep inguinal ring; 6, attachment of pelvic tendon of external oblique aponeurosis on iliopsoas and sartorius (“inguinal ligament”); 7, transversus abdominis. TVA

FIG. 21.3 The attachment of the equine abdominal muscles on the pelvis and the prepubic tendon. 1, tuber coxae; 2, transverse acetabular ligament; 2′, femoral head; 3, pubis; 4, tunica flava over linea alba; 5, prepubic tendon; 5′, accessory ligament; 6, external abdominal oblique; 6′ and 6″, pelvic and abdominal tendons of external oblique aponeurosis, respectively; 6′″, attachment of pelvic tendon of external oblique aponeurosis on sartorius and iliopsoas (“inguinal ligament”); 7, superficial inguinal ring; 8, internal abdominal oblique; 9, iliopsoas; 10, sartorius; 11, vascular lacuna containing femoral vessels; 12, femoral fascia (lamina). TVA

Schematic above – inguinal region in male (equine or bovine). Labeled structures: body wall – transversus abdominis m. and fascia, internal abdominal oblique m., external abdominal oblique m.; peritoneum, vaginal ring, deep ring, inguinal canal, superficial ring, external spermatic fascia, spermatic cord, parietal and viscera vaginal tunics, cremaster m.; pampiniform plexus (testicular v.), testicular a., ductus deferens, testis. (RLarsen)

Parturition and Dystocia

- Clinical Notes: It will be important to be aware of the dimensions of the bony pelvis when thinking about dystocia (when birthing is difficult). These include dorsal to ventral lengths, as well as the lateral boundaries (see image below). (Fig. 29.1) Sometimes it is necessary to rotate the calf in the abdomen and pelvis to allow for better positioning and delivery.

- For example, in calves the greatest width is across the greater trochanters (while in adult bovine the greatest width is across the tuber coxae). Therefore the pelvic inlet of the cow must be wider than the distance across the greater trochanters of the calf. If the inlet is not wide enough, hip lock (a type of dystocia) can occur if the head and chest of the calf pass into and through the birth canal, but the greater trochanters get stuck.

FIG. 29.1 (A) and (B), Median section of the bony pelvis of a cow. Certain obstetrical terms are illustrated in (B). 1, tuber coxae; 2, sacroiliac joint; 3, sacrum; 4, shaft of ilium; 5, cranial border of acetabulum; 6, pecten pubis; 7, obturator foramen; 8, symphysis; 9, tuber ischii; 10, lesser sciatic foramen; 11, sacrosciatic ligament; 12, greater sciatic foramen; 13, sacral promontory; 14, conjugate (the line connecting the promontory with the pecten); 15, vertical diameter (the vertical line between the pectin and the pelvic roof). TVA

- In instances of dystocia, not only can the calf get stuck in the birth canal, but this can put pressure on structures along the birth canal. Several nerves from the lumbosacral plexus (which exit via ventral sacral foramina) run along the inner walls of the pelvic canal. Unfortunately, these nerves can be compressed and damaged during parturition, leading to dysfunction in the muscles they innervate. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Nerve damage)

- The obturator n. (and artery in equine) runs along the medial aspect of each ilium and exits the pelvis through the obturator foramen to innervate the adductor mm.

- The sciatic n. is a large nerve bundle that exits the greater sciatic foramen to innervate muscles of the caudal thigh and distal limb.

- The femoral n. innervates the quadriceps mm.

- The pudendal n. innervates the rectum and internal and external genital organs (ending in the dorsal n. of the penis/clitoris). The pudendal n. accompanies the internal pudendal a. and v. caudally along the pelvic floor and over the ischial arch.

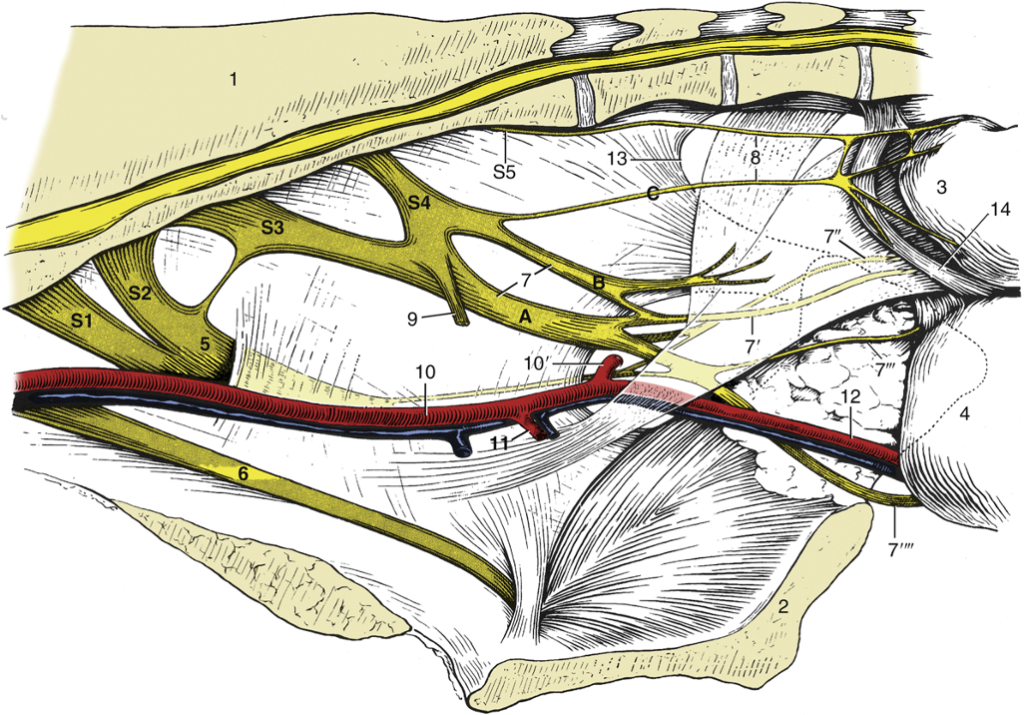

FIG. 29.5 Nerves and vessels on the medial surface of the bovine pelvic wall. Local anesthesia of the pudendal nerve (n.) can be obtained by injections at points A and B; anesthesia of the caudal rectal nerves is possible by an injection at point C. 1, Sacrum; 2, pelvic symphysis; 3, rectum (reflected); 4, vagina (reflected); 5, sciatic n.; 6, obturator n.; 7, pudendal n.; 7′, distal cutaneous branch of pudendal n.; 7″, proximal cutaneous branch of pudendal n.; 7′″, deep perineal n.; 7″″, continuation of pudendal n. to clitoris; 8, caudal rectal nerves; 9, pelvic n.; 10, internal iliac artery (a.); 10′, caudal gluteal a.; 11, vaginal a.; 12, internal pudendal a.; 13, caudal border of sacrosciatic ligament; 14, retractor clitoridis; S1 to S5, sacral nerves 1 through 5. TVA

Objective

A8.2 Identify the boundaries and structures of the perineum; describe the clinical significance of this region.

The perineum is the deep fascia and muscle that seals the pelvic outlet and encircles the terminal parts of the urogenital and digestive tracts. Perineal structures have important ‘anchors’ or attachments to help prevent displacement caused by the straining of defecation, parturition, urination, and to counteract the forward pull of a gravid uterus.

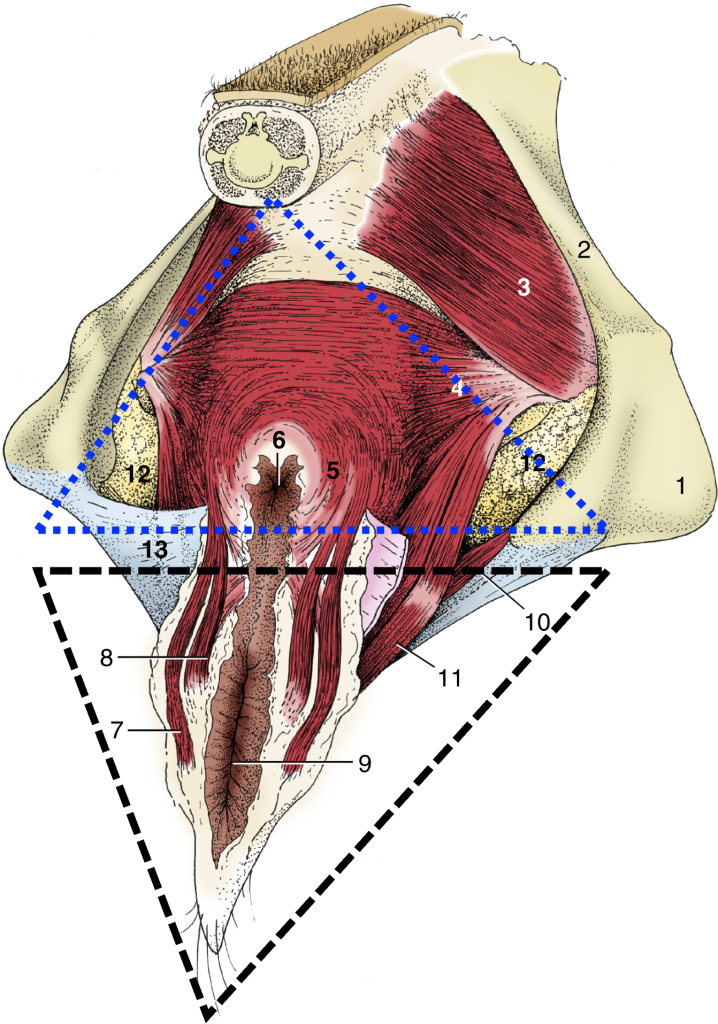

- The boundaries of the perineum include: the base of tail to the scrotum (or udder), and laterally as far as the tuber ischii. Many of the structures of the perineum in UNGULATES are similar to those discussed in CARNIVORE anatomy however, the perineal body is a new structure. The perineum can be described as two triangles. An anal triangle from the base of the tail out to the tuber ischii, and a urogenital triangle from the tuber ischii and down to the scrotum (or udder).

- Perineal structures: (Figs. 29.10, 22.14, and below)

- Pelvic diaphragm (in the anal triangle, blue dotted line below): the levator ani and coccygeus mm., which are skeletal mm., form part of a muscular sling that acts as a seal around the anorectal junction dorsally in the perineum. The levator ani has a close attachment to the external anal sphincter m., while the coccygeus mm. attach to the caudal vertebrae.

- Urogenital diaphragm (in the urogenital triangle, black dotted line below): the fibromuscular tissue (including some skeletal mm.) that anchors the reproductive and urinary tracts to the ischial arch, forming the ventral portion of the perineum that surrounds the vestibule. The muscles of this diaphragm are more slender and blend with the ventral edge of the pelvic diaphragm. These relationships of structures will be important for suturing lacerations of the perineum.

Fig. 29.10 The perineal muscles of a cow. 1, tuber ischii; 2, sacrosciatic ligament; 3, coccygeus; 4, levator ani; 5, external anal sphincter; 6, anus; 7, retractor clitoridis; 8, constrictor vulvae; 9, vulva; 10, urogenital diaphragm; 11, constrictor vestibuli; 12, fat in ischiorectal fossa; 13, perineal fascia (partly removed on the right side); blue dotted line, anal triangle around pelvic diaphragm; black dotted line, urogenital triangle around urogenital diaphragm. TVA

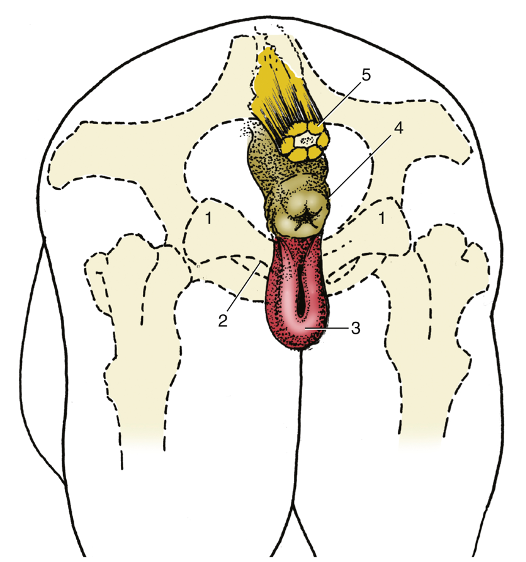

Fig. 22.14 The anus and vulva (mare) superimposed on the outline of the bony pelvis. 1, tuber ischii; 2, ischial arch; 3, vulva; 4, anus; 5, tail (section). TVA

-

- Anal sphincters: the circular muscles around the anus that tie into the fibromuscular region of the urogenital diaphragm and levator ani m. of the pelvic diaphragm.

- The external anal sphincter is skeletal m. and encircles the anus caudal to the levator ani m.

- The internal anal sphincter is smooth m. and is the deepest muscular layer in the wall of the anus.

- Perineal body: a fibromuscular structure at the midline of the perineum, between the anus and vulva (or base/root of penis). It forms multiple muscular connections (between the external anal sphincter, constrictor vestibuli, internal anal sphincter, and the retractor clitoris mm.) and forms a fibrous plate (perineal septum) between the vestibule and rectum.

- Smooth muscles: these smooth mm. attach to bone, which is rare.

- The rectococcygeus mm. runs from the dorsal aspect of rectum to the ventral aspect of vertebral column.

- The retractor penis/clitoris mm. (bilateral mm.) run from the respective reproductive organs to the vertebral column.

- Constrictor vestibulae mm.: skeletal mm. attaching to each side of the vestibule that help seal the reproductive and urinary tracts.

- Constrictor vulvi mm.: muscles along each of the vulvar labia.

- Ischiorectal fossa: a depression between the ischium and rectum, found bilaterally; it is prominent in BOVINE.

- Anal sphincters: the circular muscles around the anus that tie into the fibromuscular region of the urogenital diaphragm and levator ani m. of the pelvic diaphragm.

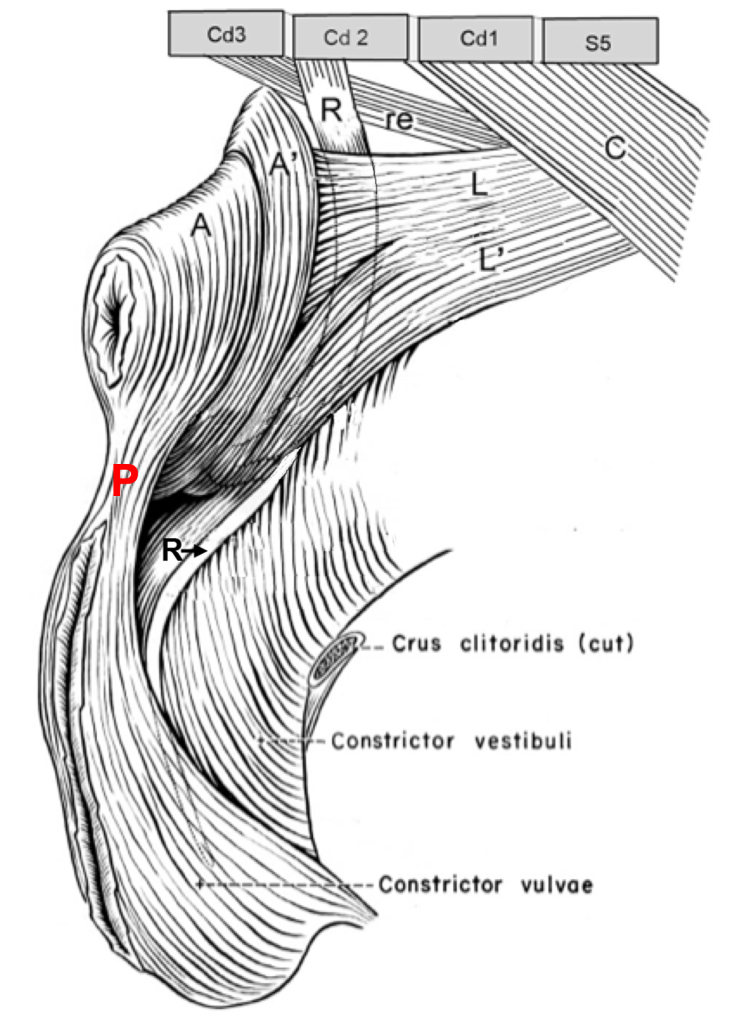

Figure above – Lateral view, isolated perineum of a MARE. A, A’, external anal sphincter m., caudal and cranial parts; C, coccygeus m.; Cd, caudal vertebrae; L, L’, levator ani m., anal and subanal parts; R, retractor clitoris m.; P, perineal body; re, rectococcygeus m.; S5, last sacral vertebral segment.

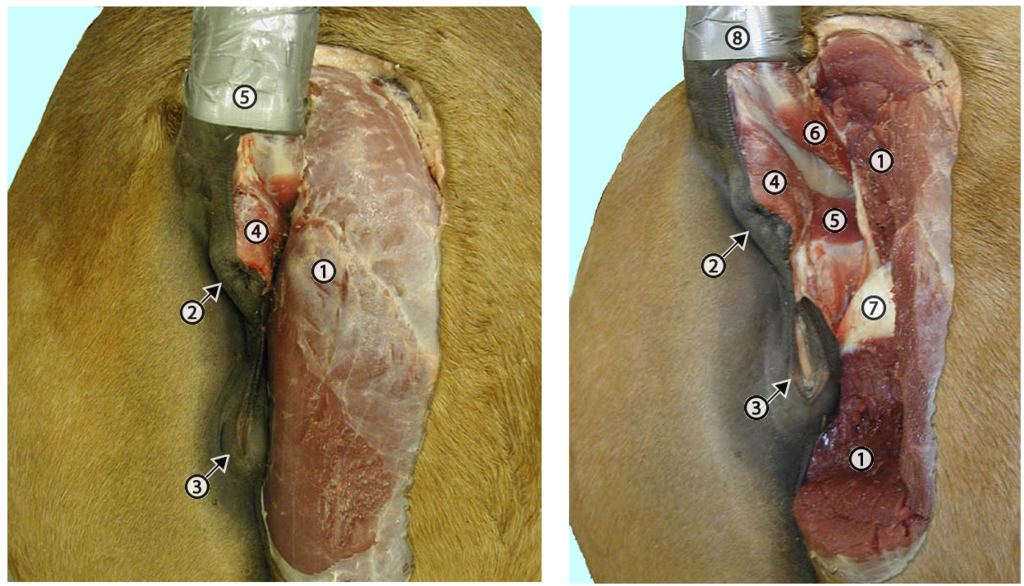

- In the MARE, the perineum is very compact due to the semimembranosus mm. that run along and over the tuber ischii, which can obscure other structures of the perineum.

- The pelvic diaphragm (formed by the levator ani and coccygeus mm.) can appear different in the MARE versus the COW, as their pelvic bones have slightly different morphology (e.g., angle of ischial arch, width) and the increased musculature in equine.

Figures above – Mare perineum. LEFT: In the horse the semimembranosus m. (1) is closely adjacent to the anus (2) and the vulva (3). Also: 4, external anal sphincter m. and 5, the tail is elevated. RIGHT: The semimembranosus m. (1) has been cut and partially removed to expose deep structures associated with the perineum. 2, anus; 3, vulva; 4, external anal sphincter muscle; 5, levator ani muscle; 6, coccygeus muscle; 7, partial exposure of the ischial arch and tuberosity; 8 tail. http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab15/Img15-7.html; http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab15/Img15-8.html

Clinical Significance of Perineum

- There are extensions of the peritoneal cavity into the pelvic region similar to those discussed in small animal anatomy: pararectal fossa, rectogenital pouch, vesicogenital pouch, pubovesical pouch. The depth of these pouches is important to consider if lacerations occur to the rectum or vagina, but usually these reflections are usually relatively far from the perineum (e.g., 10 or more inches), hence a tear and tract contents don’t often enter the peritoneal cavity.

Fig. 22.5 Median section of the pelvis of the mare. 1 and 1′, Peritoneal and retroperitoneal parts of the rectum, respectively; 2, anal canal; 3, uterus; 4, cervix; 5, vagina; 6, vestibule; 7, bladder; 8, urethra; 9, caudal extent of peritoneum. TVA

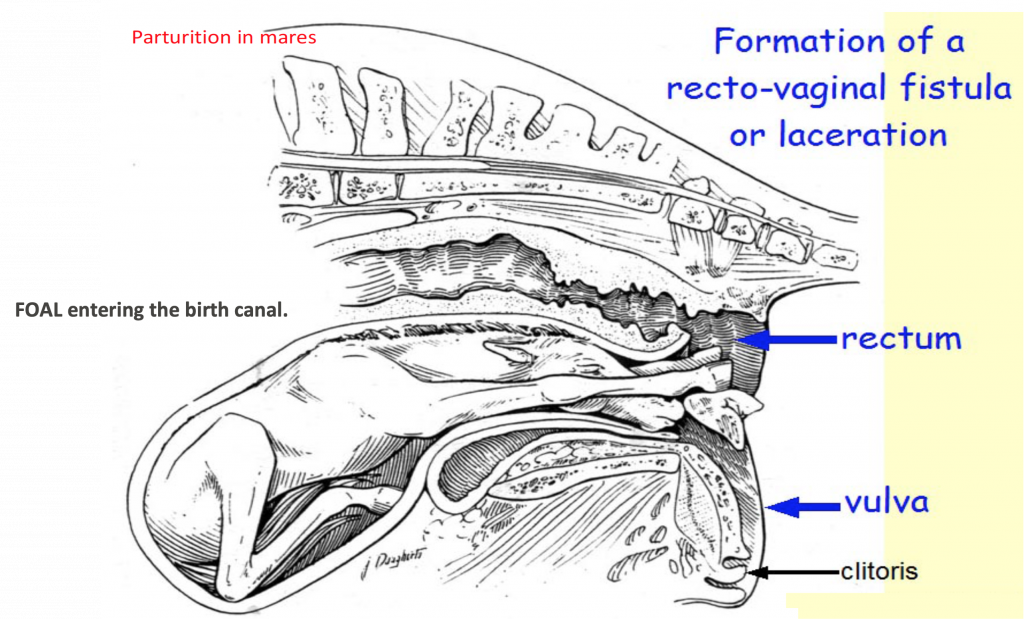

- Clinical Note: lacerations can occur in MAREs especially (but can also occur in other species), as the birthing process can happen quickly and the hooves of the foal can tear tissue in the perineal region, including near and around the perineal body. Specifically, a laceration to the tissue dorsal to the vagina, causing an opening between the rectum and vagina called a recto-vaginal fistula (see image below). It is important in these scenarios to understand the location of the perineal body as it can be used when suturing lacerations in this region. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Rectovaginal lacerations; LAS Perineal anatomy)

Figure above – parasagittal view of mare uterus and urogenital structures during delivery/parturition. The foal is entering the birth canal, forelimbs first showing the hooves lacerating the dorsal wall of the vagina and entering the rectum. Labeled structures: rectum, vulva, clitoris.

- Clinical Notes: some surgical repairs (e.g., pexy procedures – a surgical fixation of tissues to try to restore the anatomy and function of the organ) in the perineal region anchor sutures into the tough fibrous connective tissue of the sacrosciatic ligament. Therefore it is important to know (and be able to palpate) where vessels and nerves are in relation to the sacrosciatic ligament. (Fig. 29.5 and below)

- Several nerves of the lumbosacral plexus run along the inner surface of the sacrosciatic ligament, as well as the internal iliac a. and some of its branches. Remember (see above, A8.1), there are different structures exiting the greater and lesser sciatic foramina in the sacrosciatic ligament.

- In the MARE, the internal pudendal vessels and the pudendal n. are near the caudal and ventral aspect of sacrosciatic ligament.

- In the COW, these vessels and nerves exit more caudally.

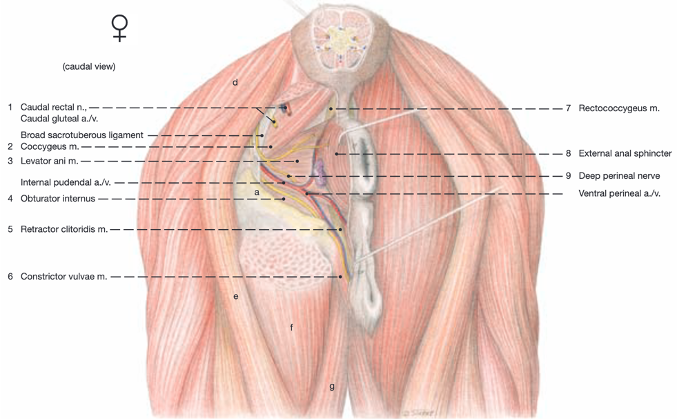

Caudal view, mare: a Tuber ischii; b Greater trochanter; c Third trochanter; d Biceps femoris m.; e Semitendinosus m.; f Semimembranosus m.; g Gracilis m.; h Gemellus mm.; i Internal obturator m.; j External obturator m.; k Quadratus femoris m.; l Adductor magnus m.; m Anorectal ln. Labeled structures: caudal rectal n.; caudal gluteal a. and v.; sacrosciatic ligament; coccygeus; levator ani; internal pudendal a. and v.; internal obturator; retractor clitoris; constrictor vulvae; rectococcygeus; external anal sphincter; deep perineal n.; ventral perineal a. and v. (Budras, Sack, Rock Anatomy of the Horse)

FIG. 29.5 Nerves and vessels on the medial surface of the bovine pelvic wall. Local anesthesia of the pudendal nerve (n.) can be obtained by injections at points A and B; anesthesia of the caudal rectal nerves is possible by an injection at point C. 1, Sacrum; 2, pelvic symphysis; 3, rectum (reflected); 4, vagina (reflected); 5, sciatic n.; 6, obturator n.; 7, pudendal n.; 7′, distal cutaneous branch of pudendal n.; 7″, proximal cutaneous branch of pudendal n.; 7′″, deep perineal n.; 7″″, continuation of pudendal n. to clitoris; 8, caudal rectal nerves; 9, pelvic n.; 10, internal iliac artery (a.); 10′, caudal gluteal a.; 11, vaginal a.; 12, internal pudendal a.; 13, caudal border of sacrosciatic ligament; 14, retractor clitoridis; S1 to S5, sacral nerves 1 through 5. TVA

- Clinical Notes: Pudendal nerve block – the pudendal n. innervates the rectum and internal and external genital organs (and ends as the dorsal n. of the penis/clitoris). The pudendal n. accompanies the internal pudendal a. and v. caudally along the pelvic floor and over the ischial arch. It provides motor innervation to the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani, coccygeus), the urogenital diaphragm (constrictor vestibuli and vulvae), the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus, and the external anal and urethral sphincters/urethralis (all skeletal mm.). The pudendal n. receives sensory input from the genitalia and perineal region. Parasympathetic autonomic branches accompany the ventral roots of the pudendal n. to form the pelvic nn. that enter the pelvic plexus. Sympathetic autonomic branches join the pelvic plexus from the hypogastric nerves. Autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nerve fibers from the pelvic plexus course with the pudendal n. to innervate smooth muscle in the internal anal sphincter, rectococcygeus, and retractor penis/clitoris mm. The pudendal n. can be blocked to perform various procedures on genital and perineal structures in the male and female. (Fig. 29.5)

- (FYI only) On the medial side of the sacrosciatic ligament via rectal palpation:

- Find the internal iliac a. (you can feel the pulsating vessel in the live animal) on the medial side of the sacrosciatic ligament, just dorsal to the ischiatic arch. Follow the artery to the lesser sciatic foramen. Alongside the internal iliac a. there may be palpable iliac lymph nodes.

- The pudendal n. is about 1cm dorsal to the point where the internal iliac a. intersects with the cranial aspect of lesser sciatic foramen.

- A needle with local anesthetic is introduced through the skin (surgical prep of ischiorectal fossa) and guided to the pudendal n. location on the medial side of the sacrosciatic ligament. For more details, see Supplemental Clinical LAS Perineal analgesia and/or Farm Animal Surgery by Fubini and Ducharme.

- (FYI only) On the medial side of the sacrosciatic ligament via rectal palpation:

Objective

A8.3 Describe the normal parts and placement of the lower urinary tract and their relationship with the pelvis and perineum.

- Ungulates have similar lower urinary tract (LUT) anatomy to small animals (carnivore anatomy):

- The ureters have a smooth muscle wall and enter into the caudo-dorsal aspect of the urinary bladder.

- The urinary bladder also has a smooth muscle wall (called the detrusor m.).

- The urethra has an internal urethral sphincter (smooth m.) near the bladder, and an external urethral sphincter/urethralis (skeletal m.) more distal. The pelvic urethra in males and females is covered by the urethralis muscle.

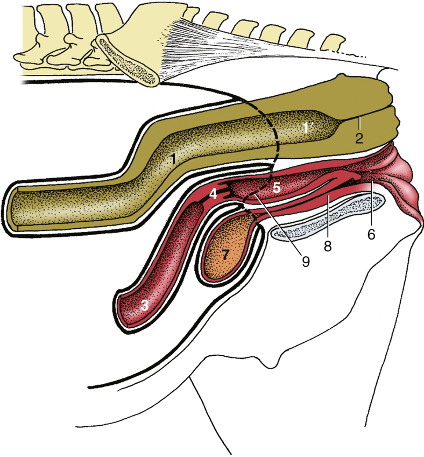

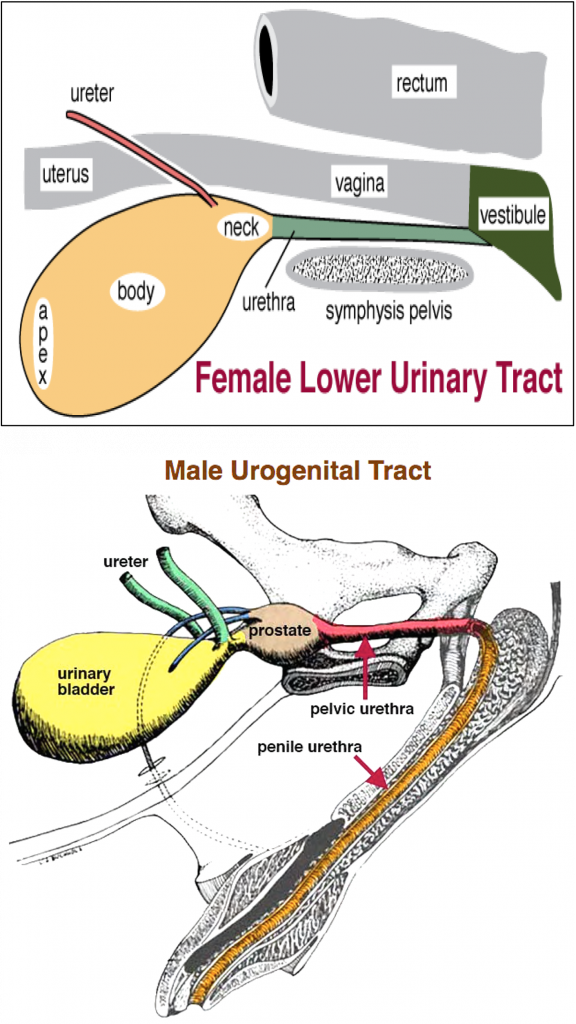

Figures above – Top: female lower urinary tract structures. Labeled structures: rectum, vagina, vestibule, urethra, urinary bladder (neck, body, apex), ureter, uterus. Bottom: male lower urinary tract. Labeled structures: ureter, urinary bladder, prostate, pelvic urethra, penile urethra.

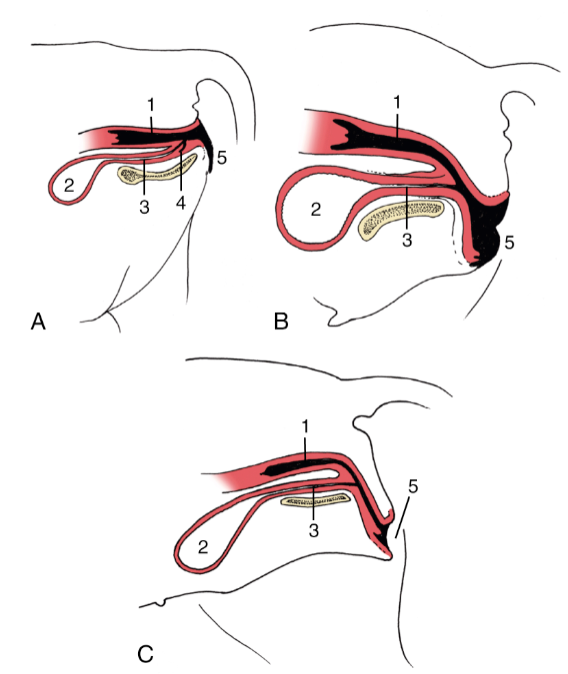

- Species similarities and differences of the lower urinary tract of females (Fig. 5.61):

- In the pelvis, the bladder is most ventral, the vagina/cervix/uterus is in the middle, and the rectum is most dorsal. In the perineum, the exits of these tracts are from ventral to dorsal: vestibule with the urethral orifice ventrally and vagina dorsally, and anus being the most dorsal structure near the base of the tail.

- In all species we discuss (MARE, COW, SOW), urine exits the bladder via the urethra and empties into the vestibule (a common urogenital region in the female) via the urethral orifice.

- In the COW and SOW, ventral and caudal to the urethral orifice is a suburethral diverticulum. This diverticulum can make catheterization of the urethra difficult.

FIG. 5.61 Variation in the position of the vestibule in relation to the ischial arch in the (A) cow, (B) mare, and (C) bitch. 1, Vagina; 2, bladder; 3, urethra; 4, suburethral diverticulum; 5, vulva. TVA

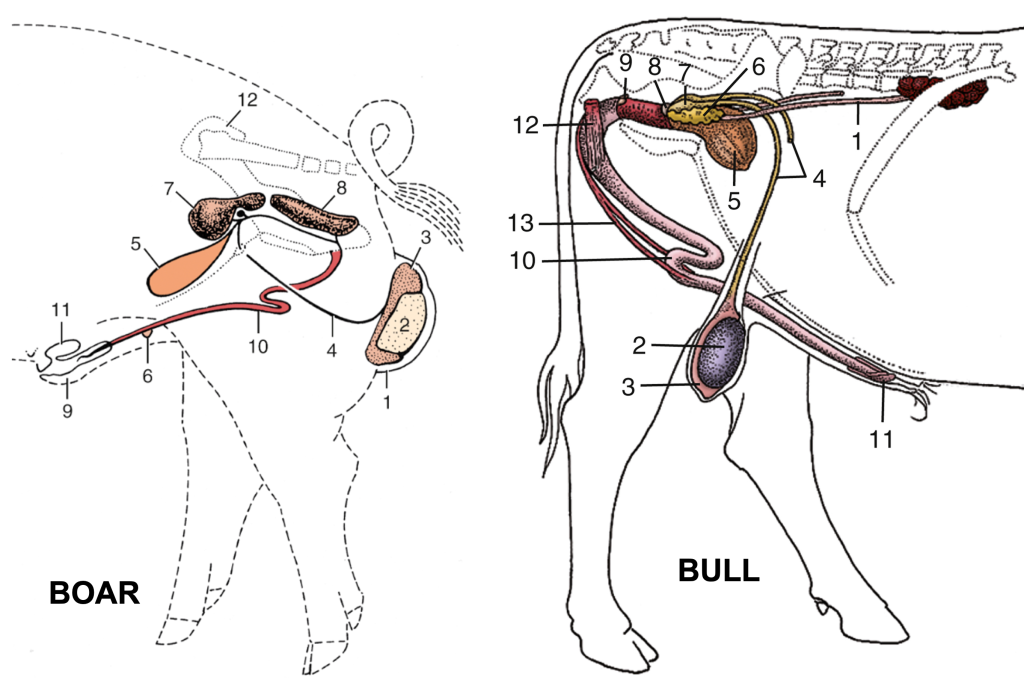

- Species similarities and differences of the lower urinary tract of males (Figs. 22.19, 29.28, 35.6):

- In the pelvis, the bladder is most ventral and the rectum is most dorsal. In the perineum, the exit of the urinary tract is the penile urethra in the free part of the penis (which is most often surrounded by the prepuce) near the ventral/abdominal wall; the exit of the rectum is the anus and is near the base of the tail.

- In all species we discuss (STALLION, BULL, BOAR), the ureters are relatively close to the ductus deferens at the caudo-dorsal aspect of the bladder and prostate. Urine exits the bladder via the pelvic urethra (surrounded by urethralis m.), then passes through the penile urethra to exit the body.

- In the BULL and BOAR there is a sigmoid flexure of the penis (causing proximal and distal loops in the urethra), as well as a urethral process (narrowing the exit of the urethra at the distal portion of the penis). Both of these features can be potential regions where the exit of urine can blocked.

- In addition to urinary structures, there are also several accessory sex glands (e.g., bulbourethral, vesicular, prostate, ampullae; the presence of particular glands varies by species, more in the next application) that add to the seminal fluid (in conjunction with sperm from the testes via the ductus deferens) at the prostatic urethra.

FIG. 35.6 (Left) Reproductive organs of the boar (schematic). 1, Scrotum; 2, left testis; 3, tail of epididymis; 4, deferent duct; 5, bladder; 6, rudimentary teat; 7, vesicular gland covering the small body of the prostate; 8, bulbourethral gland; 9, prepuce; 10, penis; 11, preputial diverticulum; 12, right hip bone.

Fig. 29.28 (Right) Disposition of the urogenital organs of a bull. 1, Ureter; 2, right testis; 3, epididymis; 4, deferent duct; 5, bladder; 6, vesicular gland; 7, ampulla of deferent duct; 8, body of prostate; 9, bulbourethral gland; 10, sigmoid flexure of penis; 11,glans penis; 12, ischiocavernosus; 13, retractor penis. TVA

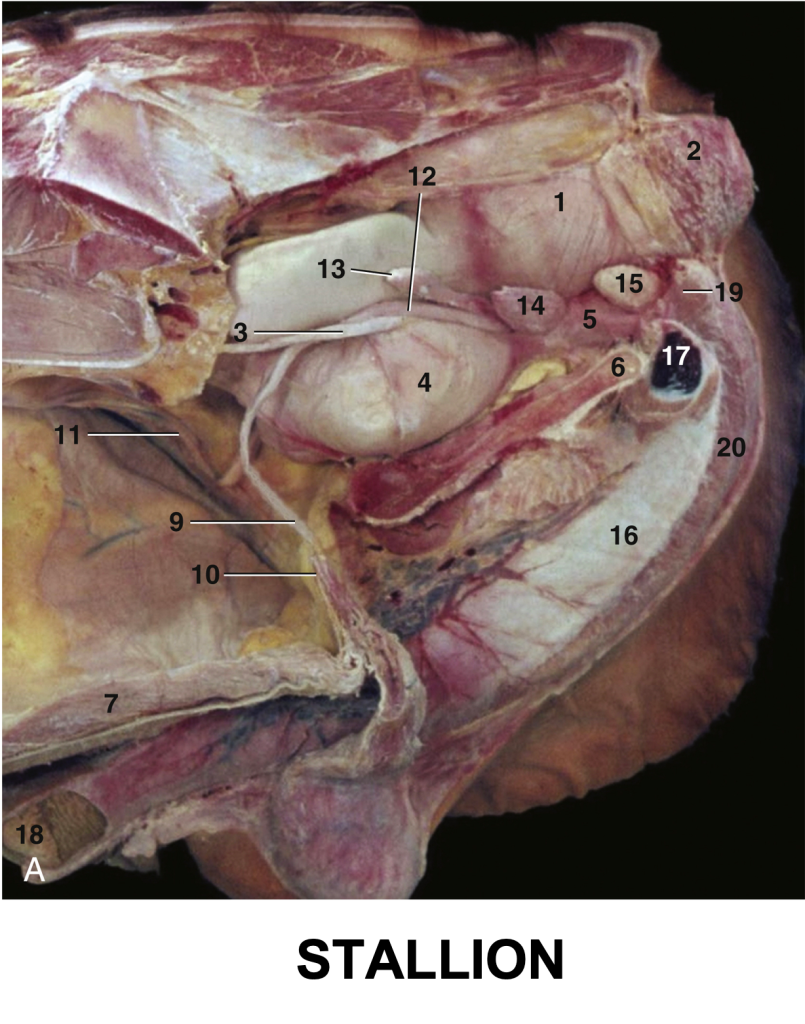

Fig. 22.19 (A) The reproductive organs of the stallion in situ. 1, Rectum; 2, external anal sphincter; 3, ureter; 4, bladder; 5, urethra; 6, floor of pelvis; 7, floor of abdomen; 9, left deferent duct; 10, vaginal ring; 11, right testicular artery and vein; 12, ampulla of deferent duct; 13, vesicular gland; 14, prostate; 15, bulbourethral gland; 16, penis; 17, left crus (in section); 18, glans penis; 19, ischiocavernosus; 20, bulbospongiosus. TVA

Objective

A8.4 Identify and describe the structures and connective tissue support of the bovine mammary glands (udder); describe the progressive changes in venous drainage of the udder with lactation.

- The COW udder consists of four mammary glands (usually referred to as ‘quarters’). Each quarter normally has one teat. Sometimes there may be supernumerary teats (any teats in excess of the normal number). (Fig. 13-12)

- There is a thick medial suspensory ligament of the udder which is yellow and elastic, and is derived from the tunica flava abdominis and attaches to the prepubic tendon. This paired midline suspensory structure completely separates the right and left portions of the mammary gland and makes surgical amputation of half of the udder possible. The suspensory ligament can lose its elasticity and cause changes in udder conformation and reduce overall support.

- The lateral laminae are relatively strong and collagenous and extend from the subpelvic tendon and medial femoral fascia, and penetrate the udder at various levels.

- In MAREs, the udder consists of a pair of mammary glands, each with one teat.

Figure 13-12 Transverse section of the abdominal floor and cranial quarters of the bovine udder. 1, external abdominal oblique; 2, internal abdominal oblique; 3, rectus abdominis; 4, peritoneum; 5, linea alba; 6, lymph vessel; 7, external pudendal vein; 8, external pudendal (mammary) artery; 9, medial suspensory ligament; 10, lactiferous sinus; 11, papillary duct; 12, lateral laminae of suspensory apparatus. (Modified from TVA Figure 29-39).

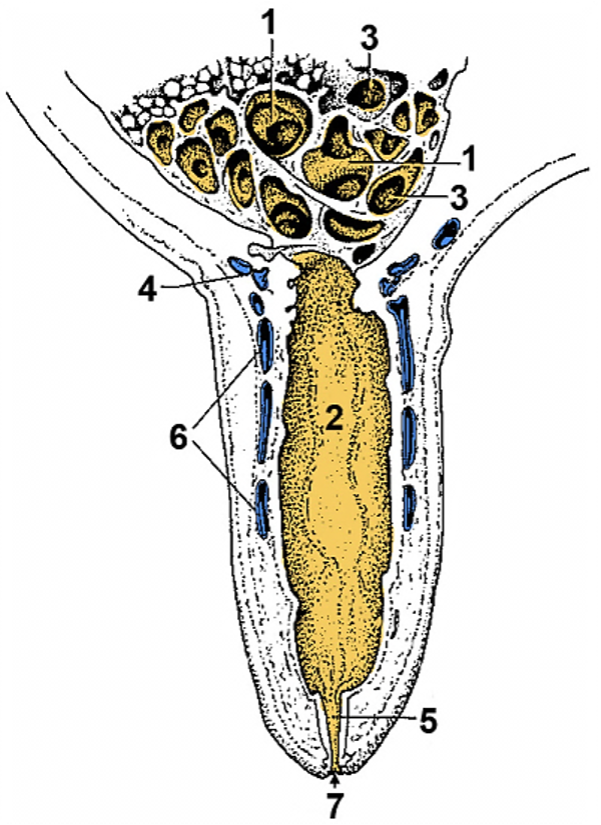

Glands, Sinuses, and Teats (Fig. 13-13)

- The fore and hind quarters of the udder cannot be distinctly separated. The gland systems are, however, completely separate. Note that the hind quarters are considerably larger than the fore quarters.

- Lactiferous ducts: the ducts (from the mammary glands) which empty into the lactiferous sinus.

- Lactiferous sinus: the collective term for the gland sinus and the teat sinus combined. The lactiferous sinus is only divided in RUMINANTS due to the large size of their teats.

- Gland sinus: proximal portion of the lactiferous sinus, separated from the teat sinus by an inconstant internal annular fold at the base of the teat.

- Teat sinus: the distal portion of the lactiferous sinus and lumen of the teat. Ultrasound can be used to attempt to visualize obstructions in the gland and teat sinuses.

- Papillary duct (aka ‘teat canal’ or ‘streak canal’): the passage connecting the teat sinus with the teat orifice. The papillary duct has a tough lining and is thrown into folds by a sphincter muscle. Tight closure of the teat canal is essential to prevent entry of ascending organisms that could lead to the development of mastitis. The lining of the teat canal is said to have antibacterial properties.

- Teat orifice: the external opening of the teat.

- MAREs have two papillary ducts on each teat that drain separate lactiferous sinuses (i.e., there are two separate duct systems that drain into each teat). Hence, each teat also has two teat orifices.

Figure 13-13 Section of a cow’s teat and lactiferous sinus. 1, 2, Lactiferous sinus = gland sinus (1) and teat sinus (2); 3, openings of lactiferous ducts into the lactiferous sinus; 4, submucosal venous ring; 5, papillary duct; 6, venous plexus in teat wall; 7, teat orifice. (Modified from TVA 3rd ed., Fig. 31-5

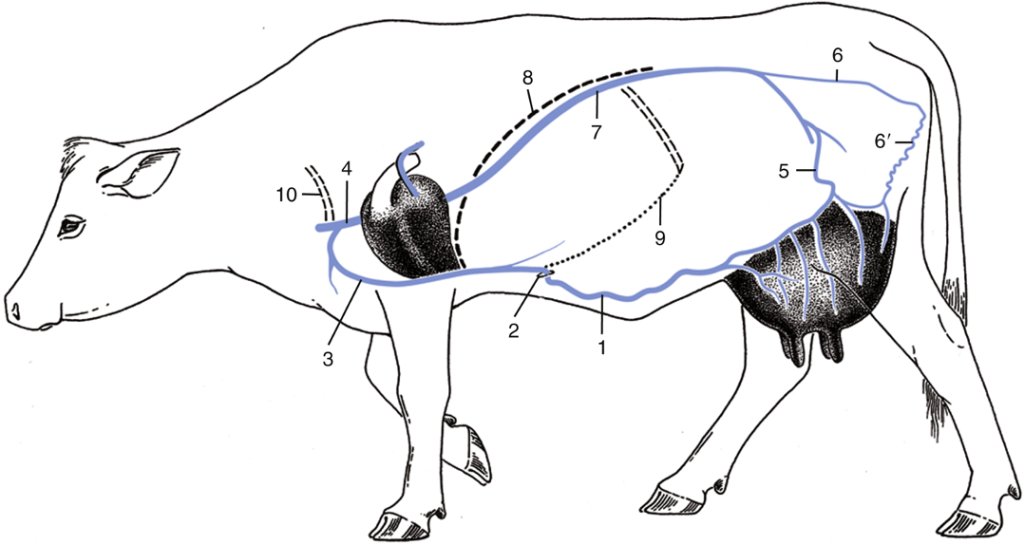

Blood Supply of the Udder (Figures 13B-8, 29.45, 29.44)

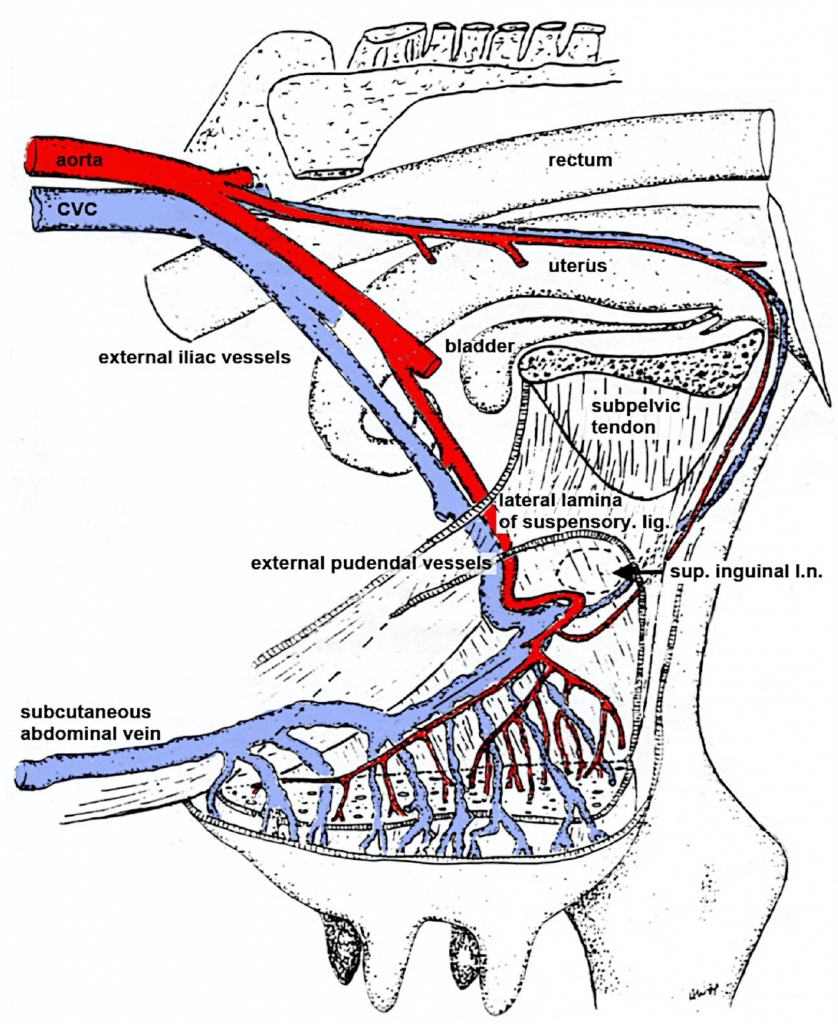

- The external pudendal a. and v. are on the caudo-lateral edge of the mammary gland. The external pudendal vv. course along the dorsal rim of the udder as they form a venous ring (i.e., around the base of the udder). Additionally, the base of each teat has a venous ring and is highly vascularized. (Fig. 13-13)

- In lactating cows, the paired subcutaneous abdominal vv. (aka ‘milk veins’) extend cranially from the venous ring to the so called “milk well.” At each well (right and left), the subcutaneous abdominal v. penetrates the body wall and joins the internal thoracic v. (Note, the internal thoracic vv. course with the internal thoracic aa. along the internal aspect of the sternum).

- The subcutaneous abdominal v. hypertrophies (i.e., enlarges) with each lactation so that it is readily visible in mature individuals. The subcutaneous abdominal v. is the result of the merging and enlargement of the cranial and caudal superficial epigastric vv.

- The PRIMARY (i.e., first to form) venous drainage of the udder is through the external pudendal v., to the external iliac v., and then the caudal vena cava.

- The SECONDARY venous drainage adds a route from the external pudendal v., to the subcutaneous abdominal v., and to the internal thoracic v. This route can be poorly developed in heifers and can result in udder edema (caked udder) in these individuals, due to insufficient venous drainage.

- The typical venous drainage of the abdominal wall in non-lactating or young animals:

- Cranial superficial epigastric vv. > internal thoracic vv. > cranial vena cava

- Caudal superficial epigastric vv. > external pudendal vv. > external iliac vv. > caudal vena cava

Fig. 29.44 The venous drainage of the bovine udder. 1, Subcutaneous abdominal (“milk”) vein (v.); 2, “milk well”; 3, internal thoracic v.; 4, cranial vena cava; 5, external pudendal v.; 6, internal pudendal v.; 6′, ventral labial v. (connecting ventral perineal v. with caudal mammary veins); 7, caudal vena cava; 8, diaphragm; 9, costal arch; 10, first rib. TVA

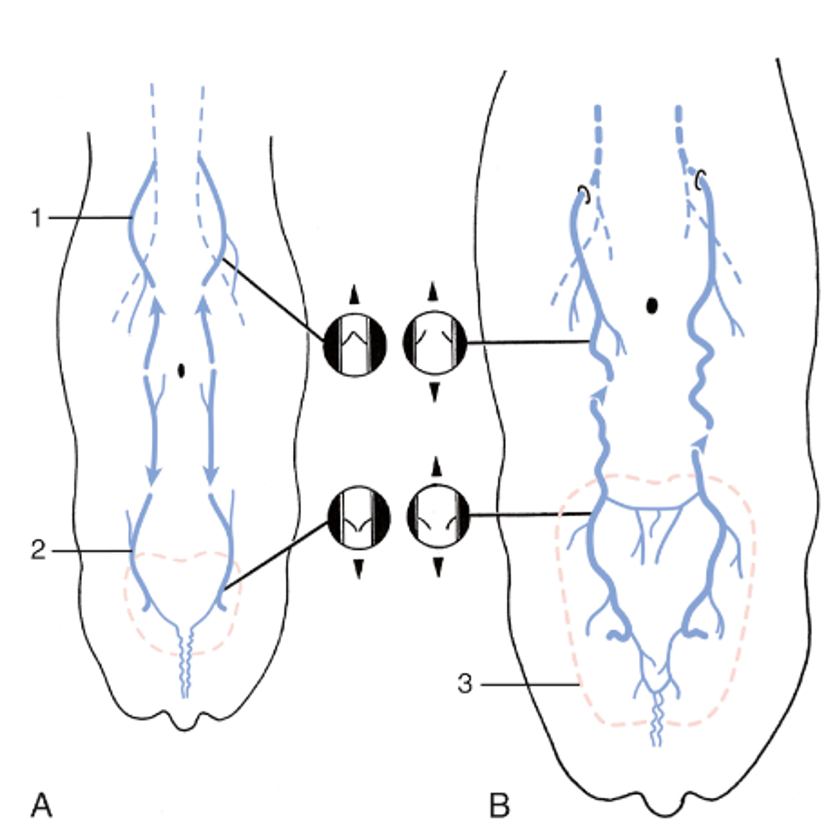

FIG. 29.45 Development of the subcutaneous abdominal veins (schematic dorsal view). (A) The region drained by the cranial superficial epigastric vein (1) is separated from that of the caudal superficial epigastric vein (2) in the calf and heifer. The valves in the cranial superficial epigastric vein direct blood cranially, while those in the caudal superficial epigastric vein direct blood caudally. (B) The subcutaneous abdominal vein is formed during pregnancy. The increased blood flow through the enlarging udder (3) causes the veins to distend, the valves to become inefficient, and the two drainage regions to unite, which allows blood to flow in both directions. TVA

Figure 13B-8 Bovine udder, left lateral view (left limb removed). The subcutaneous abdominal vein represents the well-developed superficial epigastric veins in a lactating cow. Labeled structures: aorta, CVC caudal vena cava, external iliac vessels, external pudendal vessels, subcutaneous abdominal v., rectum, uterus, bladder, subpelvic tendon, lateral lamina, superficial inguinal lymph node. (Modified from original drawing by Dr. Alvin Weber).

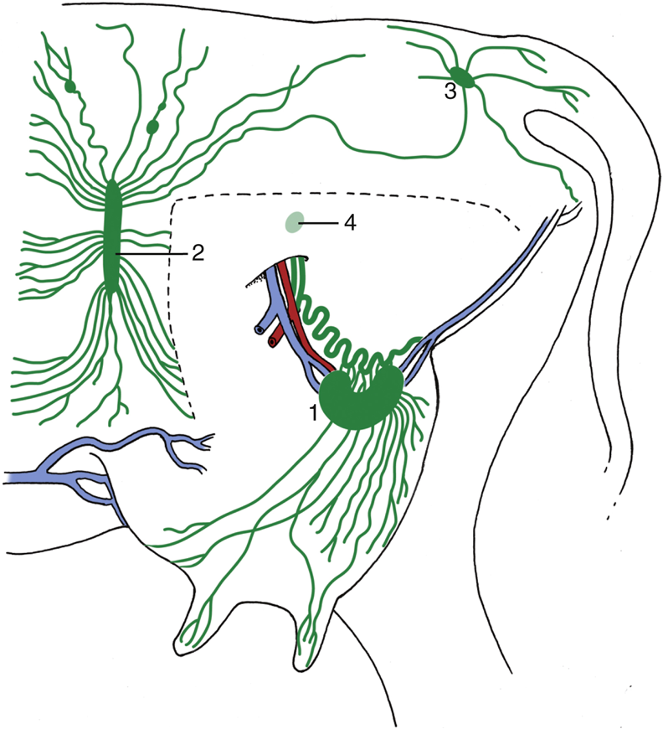

Lymph Nodes (Figure 29.46)

- Note that the BOVINE has large paired mammary lymph nodes which lie near the caudal edge of the base of the udder. These nodes may be greatly enlarged in cattle with mastitis. They are actually superficial inguinal lymph nodes, and drain via the inguinal canal to the deep inguinal lymph nodes.

Fig. 29.46 Lymph drainage of the udder. The broken line indicates where the left limb was removed to expose the udder. 1, Mammary (superficial inguinal) lymph node; 2, subiliac lymph node; 3, ischial lymph node; 4, position of deep inguinal (iliofemoral) node. TVA

Objective

A8.5 Summarize the arterial branches of the external and internal iliac aa. in terms of the region(s) supplied.

External Iliac Branches

- The abdominal aorta gives rise to the right and left testicular or ovarian aa. (aka gonadal aa., more on these and their veins in the next Application on the reproductive tracts), external iliac aa., as well as internal iliac aa. The testicular vv. and ovarian vv. return to the renal vv. or directly into the caudal vena cava. These gonadal vv. are typically running alongside the gonadal aa.

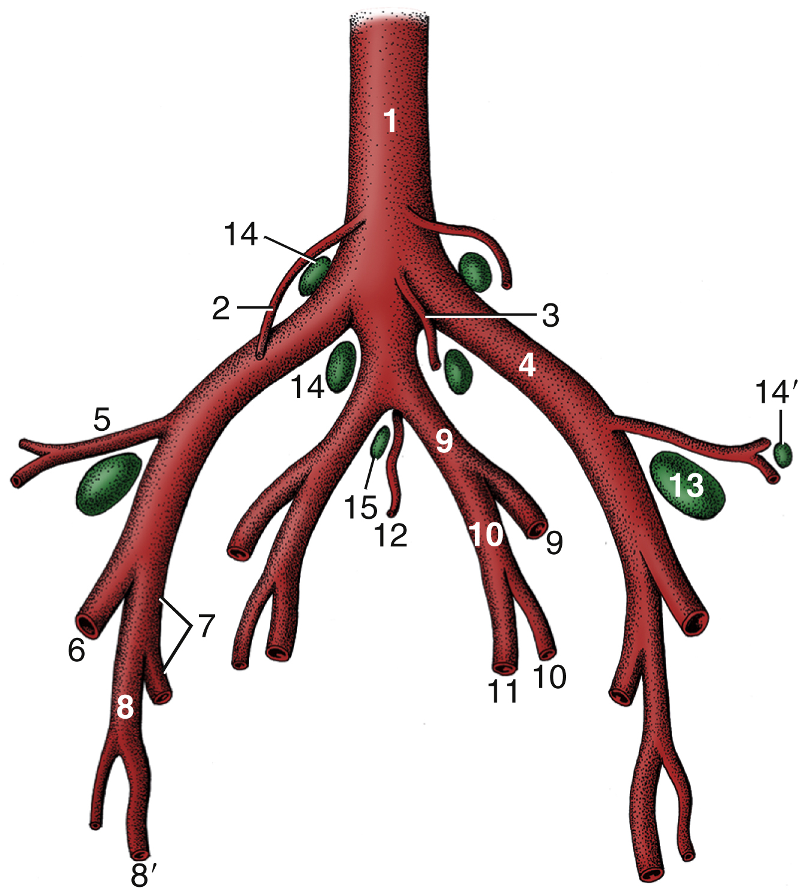

- Near the termination of the abdominal aorta and the iliac aa., there may be several lymph nodes (e.g., external iliac/deep inguinal, sacral). Fig. 29.4 shows the external iliac/deep inguinal lymph nodes (in bovine) near the external iliac and deep circumflex iliac aa.

- As always, there can be variation in the patterns described. Those described are provided as the most common arterial branching patterns.

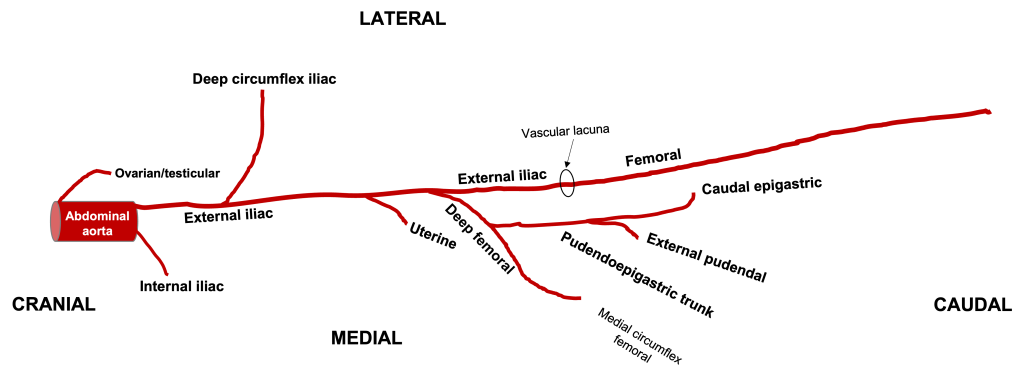

- Branches of the external iliac include:

- The deep circumflex iliac a., which branches near the edge of the pelvis/pelvic inlet.

- The deep femoral a., which branches medially, before the external iliac reaches the body wall.

- The deep femoral a. gives rise to a pudendoepigastric trunk, which has two terminal branches the external pudendal a. (provides blood to the udder/scrotum) and the caudal epigastric a. (caudal and ventral abdominal wall).

- The femoral a., which continues into the hindlimb once the external iliac passes through the body wall and vascular lacuna. In EQUINE, the deep inguinal lymph nodes are near the femoral triangle (femoral a. & v., saphenous n.).

- In EQUINE, the external iliac also gives rise to the uterine a. (branching toward the uterine body).

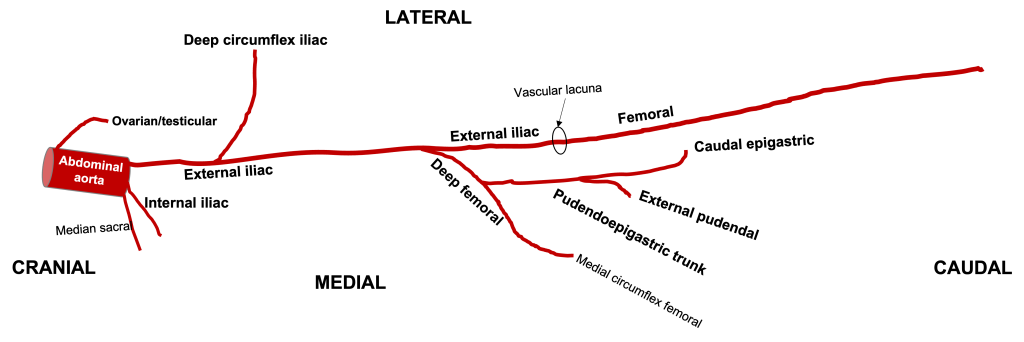

Figure above – ventral view onto the left external iliac artery and branches in the equine. Labeled branches: abdominal aorta, ovarian/testicular, internal iliac, external iliac, deep circumflex iliac, uterine (if female), deep femoral, pudendoepigastric trunk, external pudendal, caudal epigastric, femoral. All arteries are bilateral except for the aorta. (RLarsen)

Figure above – ventral view onto the left external iliac artery and branches in the bovine. Labeled branches: abdominal aorta, ovarian/testicular, internal iliac, external iliac, deep circumflex iliac, deep femoral, pudendoepigastric trunk, external pudendal, caudal epigastric, femoral. All arteries are bilateral, except for median sacral and the aorta. (RLarsen)

Fig. 29.4 Branching pattern of the caudal part of the bovine abdominal aorta. 1, Aorta; 2, ovarian artery; 3, caudal mesenteric artery; 4, external iliac artery; 5, deep circumflex iliac artery; 6, femoral artery; 7, deep femoral artery; 8, pudendoepigastric trunk; 8′, external pudendal artery; 9, internal iliac artery; 10, umbilical artery; 11, uterine artery; 12, median sacral artery; 13, deep inguinal (iliofemoral) lymph node; 14 and 14′, medial and lateral iliac lymph nodes, respectively; 15, sacral lymph nodes. TVA

Internal Iliac Branches

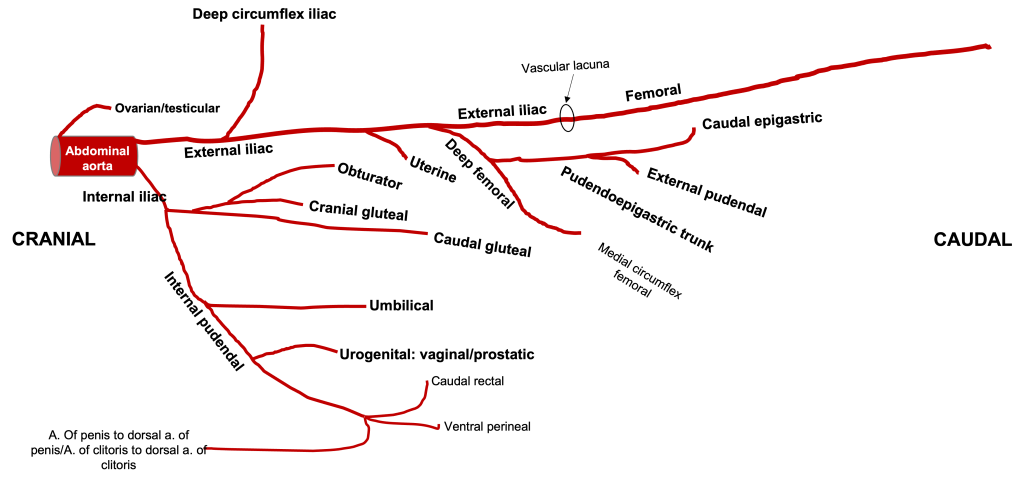

- In the HORSE, the internal iliac a. gives rise to two main branches the “wall branch” and the “visceral branch” (caudal gluteal and internal pudendal aa., respectively) at a relatively proximal point in the pelvic cavity.

- The caudal gluteal a. gives rise to the cranial gluteal a. The cranial gluteal usually gives rise to the obturator a., which is only in the HORSE. It follows the obturator n. through the obturator foramen and is an important vascular supply to the equine penis.

- The internal pudendal a. usually gives rise to the umbilical a. (going towards the bladder and ventral body wall) first, then the urogenital (prostatic/vaginal), and terminates as the dorsal a. of the penis/clitoris.

Figure above – ventral view onto the left external and internal iliac arteries and branches in the equine. Labeled branches: abdominal aorta, ovarian/testicular, external iliac, deep circumflex iliac, uterine (if female), deep femoral, pudendoepigastric trunk, external pudendal, caudal epigastric, femoral; internal iliac, caudal gluteal, cranial gluteal, obturator, internal pudendal, umbilical, urogenital (vaginal/prostatic), dorsal a. of the clitoris/penis. All arteries are bilateral except for the aorta. (RLarsen)

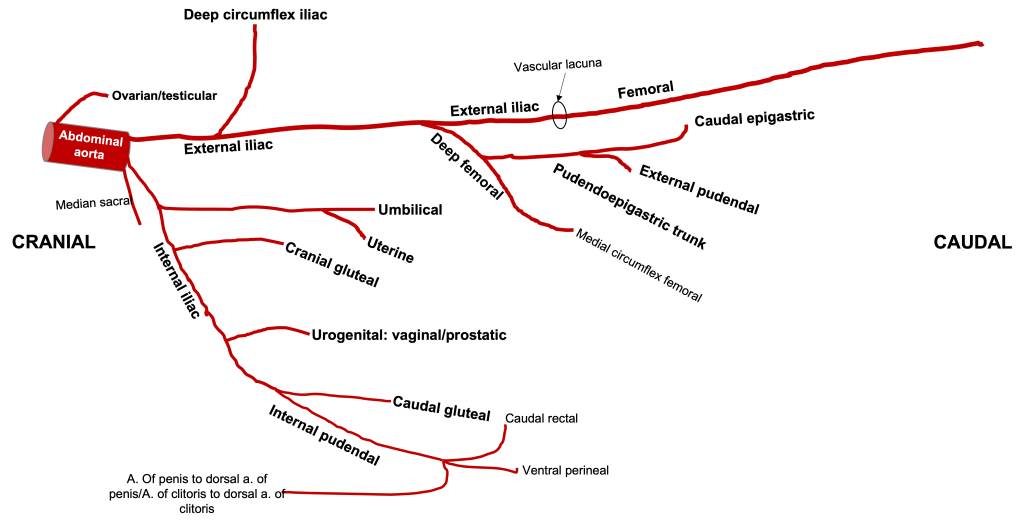

- In BOVINE, there is a relatively long internal iliac, which gives rise to the umbilical a. first (which may also give rise to the uterine a.), then the cranial gluteal a., the lastly the urogenital a. (prostatic/vaginal) before splitting into the caudal gluteal and internal pudendal aa. In BOVINE, the split of the caudal gluteal and internal pudendal aa. occurs more distally than in EQUINE, and is near the lesser sciatic foramen. The internal pudendal terminates as the dorsal a. of the penis/clitoris.

Figure above – ventral view onto the left external and iliac arteries and branches in the bovine. Labeled branches: abdominal aorta, ovarian/testicular, external iliac, deep circumflex iliac, deep femoral, pudendoepigastric trunk, external pudendal, caudal epigastric, femoral; internal iliac, umbilical, uterine, cranial gluteal, urogenital (vaginal/prostatic), internal pudendal, caudal gluteal, dorsal a. of the clitoris/penis. All arteries are bilateral, except for median sacral and the aorta. (RLarsen)

Notes on specific arteries:

- In the fetus, the umbilical a. carries deoxygenated blood to the placenta for oxygenation. In the adult, the remnant of the umbilical a. is the round ligament of the bladder (located in the lateral ligament of the bladder).

- The uterine a. is the primary blood supply to the uterus.

- In the HORSE, the uterine a. arises from the external iliac a.

- In COW, the uterine a. arises from the umbilical a.

- The uterine a. can be felt on rectal palpation in the pregnant cow. The turbulent flow of blood creates a buzzing called “fremitus.”

- The urogenital (prostatic/vaginal) a. supplies blood to many pelvic and reproductive organs.

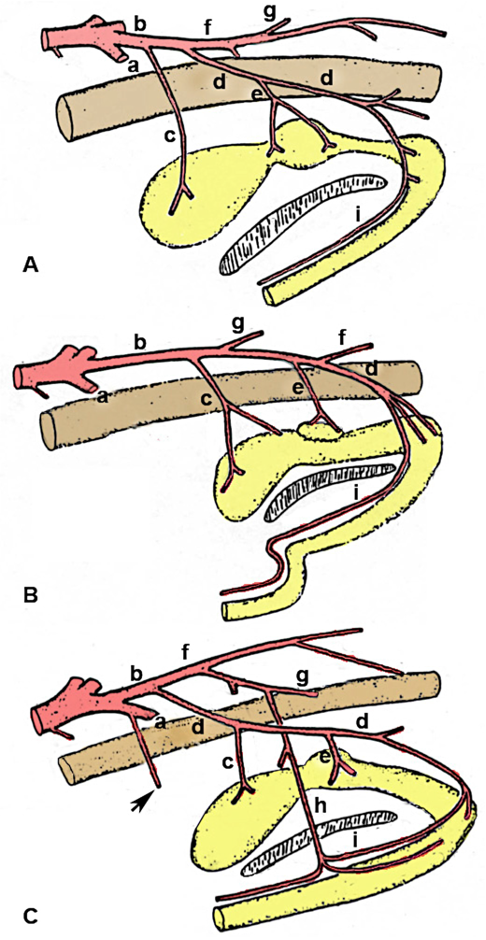

Figure 13-1 – Comparative anatomy of the pelvic arteries in the MALE, schematic lateral view. A, Canine; B, Bovine; C, Equine. a, External iliac a. b, internal iliac a. c, umbilical a. d, internal pudendal a. (to pelvic viscera) e, urogenital a. [prostatic (male), vaginal (female)] f, caudal gluteal a. (to pelvic wall) In the bovine, note the long common trunk which distally terminates into identifiable caudal gluteal/internal pudendal branches) g, cranial gluteal a. h, obturator a. (horse only) i, dorsal artery of the penis. Drawing is a modification of the original artwork by Dr. Alvin Weber.