9 Reproductive Tracts and Genitalia

Revised Spring 2024 by T. Clark

Additional Resources for this Chapter:

- Related Supplemental Large Animal Surgery links: LAS Ruminant urolithiasis; LAS Penile injury; LAS Penile injury; LAS Vaginal prolapse; LAS Pexy structures; LAS Caslick’s suture; LAS Perineal anatomy; Urine pooling; Colpotomy

- Veterinary Gross Anatomy Ungulate Dissection (Pelvis Labs 15-17)

- Associated Video Links:

- Isolated Boar, Ram, Goat Genitalia (11:45)

- Isolated Mare, Cow Genitalia (7:22)

- Isolated Male Repro Specimens (4:43)

- Mammary Gland (2:20)

Be aware of terminology differences:

-

- The uterine tube of anatomy = oviduct of theriogenology and animal science (eponym Fallopian tubes).

- Theriogenology

- therio- (Gk.) refers to animals

- genology (L.) refers to the science of genesis (reproduction)

- The ductus deferens of anatomy = vas deferens of surgery.

Objective

A9.1 Identify and describe the various parts of the male reproductive tract; identify associated structures of the ungulate testis.

Testis and Associated Structures (Figs. 9-12, 9-14, 5.41)

- The inguinal canal is a potential space between the abdominal oblique mm., through which the spermatic cord and testis (in the male) and external pudendal a. and v. (male and female) pass. It extends from the deep inguinal ring to the superficial inguinal ring.

- Clinical Note: incomplete descent of one or both testes (i.e., cryptorchidism) is common in the HORSE. Due to the close relationship of the external pudendal v. and the inguinal region, it can be traumatized during cryptorchid castration.

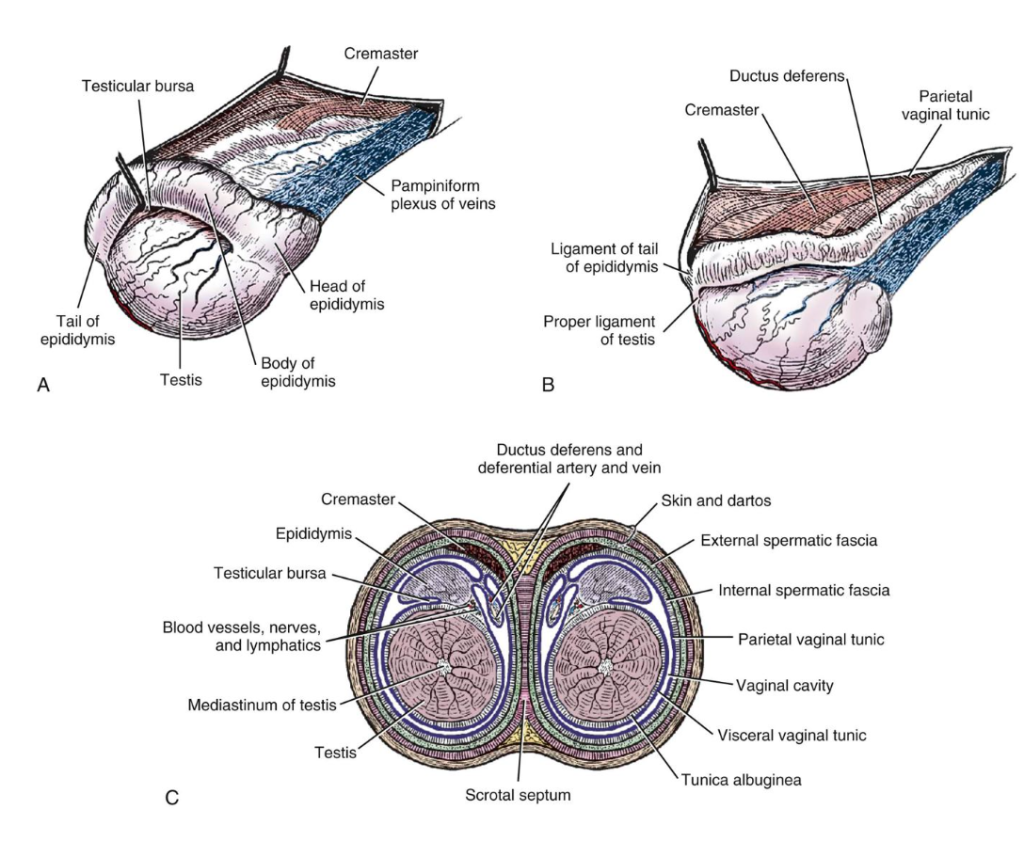

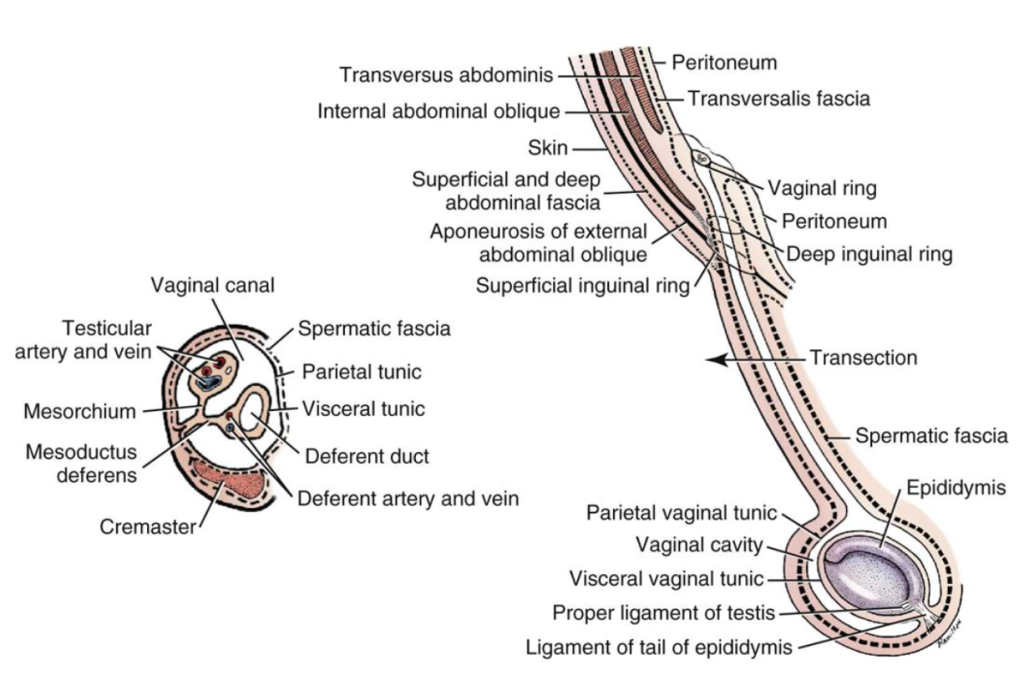

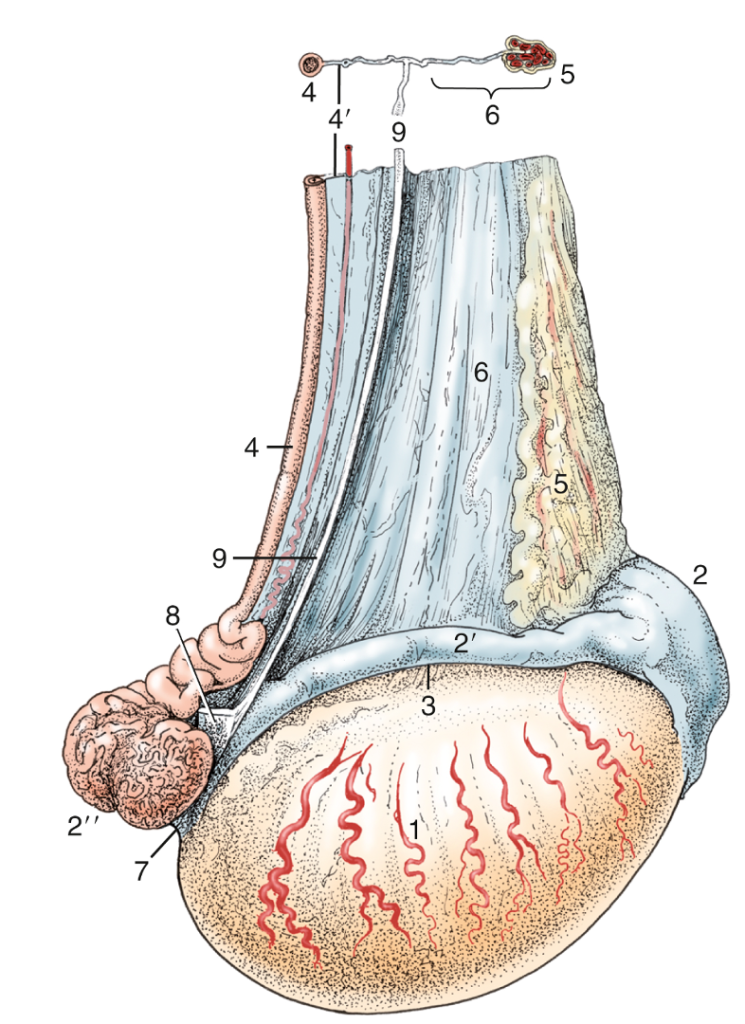

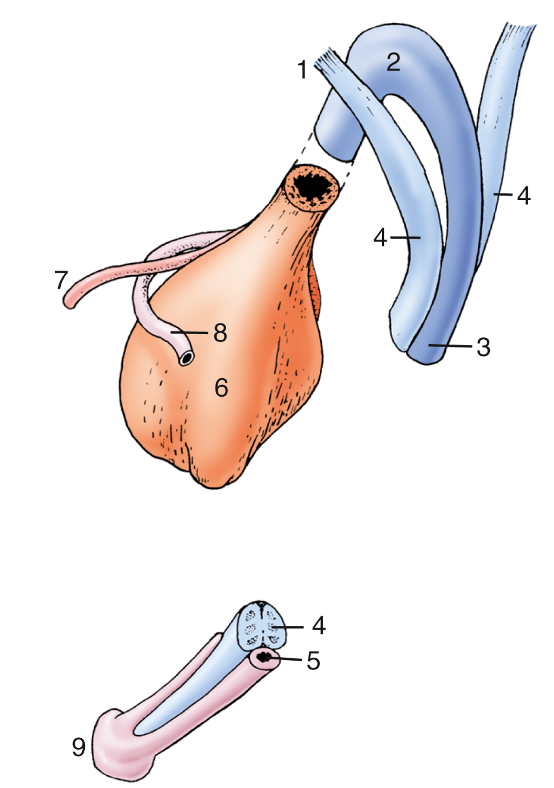

- The spermatic cord is comprised of the ductus deferens, testicular a., testicular v./pampiniform plexus, testicular nerve, and lymphatics. (Fig. 9-12, 5.41)

- The testis, epididymis, and components of the spermatic cord are encapsulated by the parietal and visceral vaginal tunics. (Fig. 9-12, 5.41)

- Visceral vaginal tunic encircles the ductus deferens and forms a supporting mesentery called the mesoductus deferens. Visceral vaginal tunic encircles the testicular vessels, nerve and lymphatics and forms a supporting mesentery called the mesorchium.

- The parietal and visceral vaginal tunics create a vaginal cavity between them that freely communicates with the peritoneal cavity through the vaginal ring.

- The vaginal tunics are serous membranes which produce a small amount of serous fluid to allow the testis and spermatic cord to move friction-less within the vaginal cavity.

- Clinical Notes: The vaginal cavity provides a possible route for the herniation of intestines that may even reach the scrotum. Indirect inguinal hernias, where the contacts pass through the vaginal ring into the vaginal cavity, are the most common type of inguinal hernias in HORSES. These are a comparatively common sequela to castration. Direct inguinal hernia, in which a loop of intestine forces an entry into the canal beside the vaginal tunic, is rare in HORSES.

- The cremaster m. (skeletal m.) arises from the caudal edge of the internal abdominal oblique m. and courses alongside the spermatic cord. The cremaster m. is in a layer of fascia just outside of the parietal vaginal tunic (cross sectional image below, C) and helps in pulling up the testis (and contracts sporadically). (Fig. 9-14)

- The tunica dartos (smooth m.), found just deep to the skin of the scrotum, can have sustained contraction and helps hold the testis close to the body for warmth, since a specific temperature is needed for spermatogenesis. (Fig. 9-14)

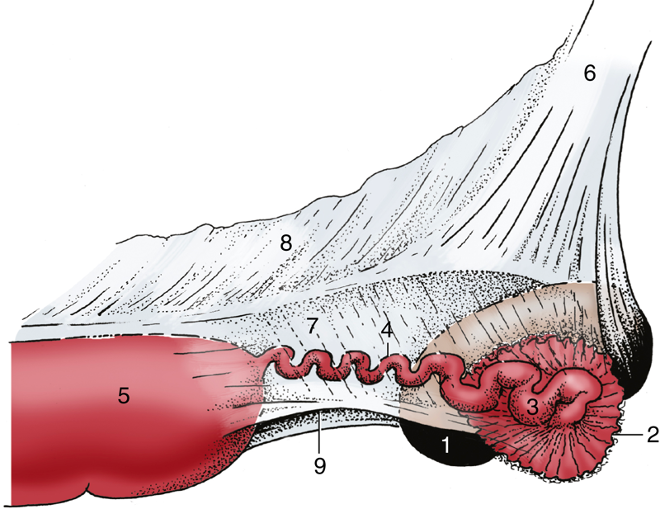

- Determining a right from a left testis: (Fig. 9-14, 5.41)

- This may be important when castrating animals or if they have cryptorchidism.

- From a lateral view, the testicular vessels enter/exit the cranial pole of a testis near the head of the epididymis (the head of the testis is toward the head of the animal). Tubes within the testis produce sperm that enter into the epididymis. The epididymis also has a body, while the tail is near the caudal pole of the testis (toward the tail of the animal).

- Along the lateral side of the epididymis there is a testicular bursa (a space between the epididymis and testis).

- Using the testicular bursa and the position of the head or tail of the epididymis, you should be able to differentiate right and left testes.

- From a medial view, the ductus deferens leads away from the tail of the epididymis.

- Note, while BOAR testes are similar to other species, the tail of the epididymis is very large.

Fig. 9-14 Structures of testes and scrotum in canine. A, Right testis, lateral aspect. B, Left testis, medial aspect. C, Schematic cross section through scrotum and testes. Labeled structures: cremaster m., pampiniform plexus/testicular v., epididymis (head, tail, body), testicular bursa, testis, ligament of the tail of the epididymis, proper ligament of the testis, ductus deferens; skin and tunica dartos, spermatic fascia (external, internal), vaginal tunics (parietal, visceral), vaginal cavity, tunica albuginea, scrotal septum, mediastinum of testis. (Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog)

Fig. 9-12 Schema of the vaginal tunic in the male canine with an inset of a transection. Labeled structures: transversus abdominis, internal abdominal oblique, transversalis fascia, peritoneum, skin, aponeurosis of external abdominal oblique, superficial inguinal ring, deep inguinal ring, vaginal ring, spermatic fascia, vaginal tunics (parietal, visceral), vaginal cavity, ligament of the tail of the epididymis, proper ligament of the testis, epididymis, testicular a. and v., mesorchium, mesoductus deferens, cremaster, spermatic fascia, ductus deferens. (Evans HE, de Lahunta A: Miller’s guide to the dissection of the dog, 3rd ed.)

FIG. 5.41 Lateral view of the right testis of a stallion. 1, Testis; 2, head of epididymis; 2′, body of epididymis; 2′′, tail of epididymis; 3, testicular bursa; 4, ductus deferens; 4′, mesoductus deferens; 5, pampiniform plexus/testicular v.; 6, mesorchium; 7, proper ligament of testis; 8, ligament of tail of epididymis; 9, cut edge of fold connecting visceral and parietal layers of the vaginal tunic. TVA

Objective

A9.2 Identify and describe the gross morphology and basic functional role of the accessory sex glands in the stallion, bull, and boar; summarize differences seen amongst these species.

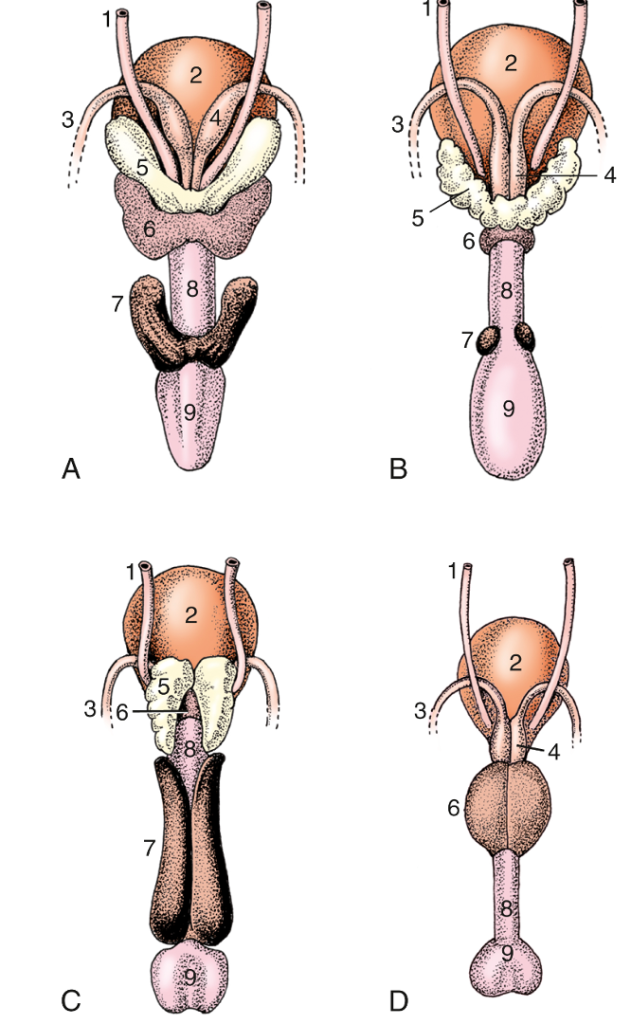

- The functions of the accessory sex glands are to contribute to ejaculate or seminal fluid (the fluid component of semen for sperm to travel with during ejaculation). Each contributes to varying degrees, and can be particular to a species. All glands are paired (i.e., bilateral) except the prostate.

- One developmental structure to note is the genital fold, a membrane connecting the ductus deferens. Within this fold there may be a remnant of the paramesonephric ducts, called the uterus masculinus. If present, it will appear as a midline thickening.

- The types of glands include (each species is described further below):

- Ampullae/ampullary glands – present in ruminants, horses, dogs, but absent in cats and poorly developed in the boar. It is typically a widening or enlargement of the wall of the distal portion of the ducts deferens.

- Vesicular glands – present in some form in horses, ruminants, swine but absent in the dog and cat. Vesicular glands in the horse are often referred to as seminal vesicles because they are sac-like with a lumen.

- Prostate – present in all domestic mammal species.

- Bulbourethral glands – present in all domestic mammal species except the dog. Located at the ischial arch, caudal to the other glands.

- The table below helps to clarify the presence of each gland in species and if there are size or shape differences in the various species. See Fig. 5.51 below as well (dorsal view of the glands in each species).

| Glands: | ampullary | vesicular | prostate | bulbourethral |

| stallion | present | U-shape, with lumen | large butterfly | U-shape |

| bull | present, slight | U-shape | ring | small |

| boar | not present | present | small | long, well developed |

| dog | may be present | not present | rounded | not present |

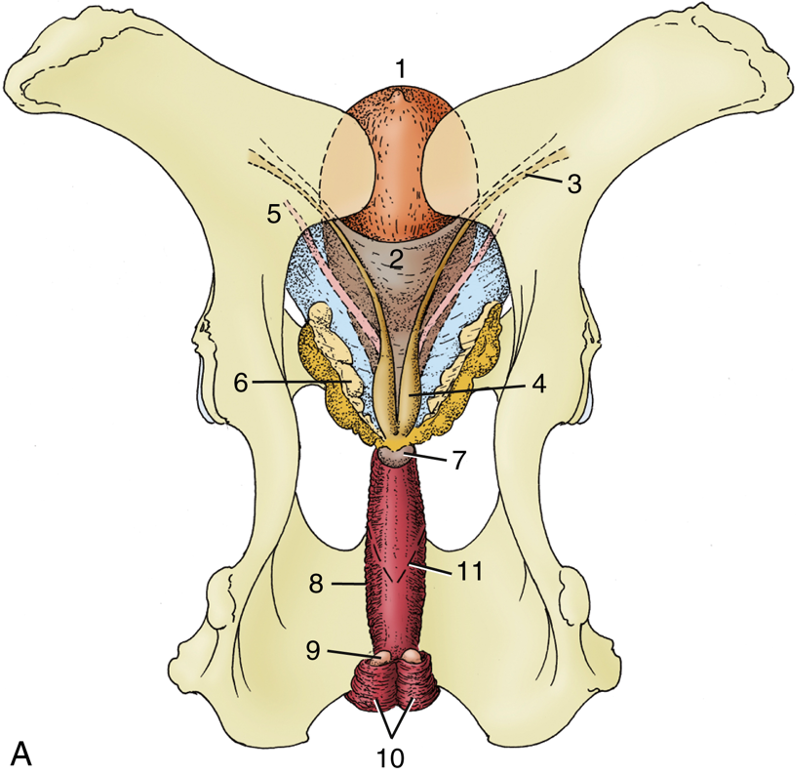

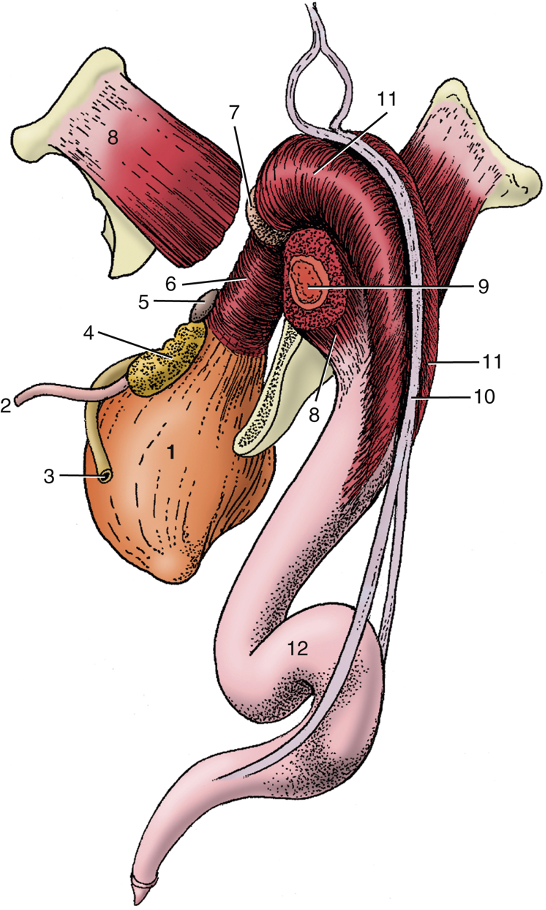

FIG. 5.51 Accessory reproductive glands of the (A) stallion, (B) bull, (C) boar, and (D) dog, dorsal view. 1, Ureter; 2, bladder; 3, ductus deferens; 4, ampullary gland; 5, vesicular gland; 6, body of prostate; 7, bulbourethral gland; 8, urethra, 9, bulb of penis. TVA

Stallion Accessory Sex Glands (Figs. 13-4, 5.51)

- The ampullae (aka ampullary glands) are enlargements of the wall of the distal portion of the ductus deferens (paired).

- The vesicular glands or seminal vesicles (paired) are smooth, sack-like structures lateral to the ampullae.

- The (body of the) prostate gland is unpaired and surrounds the urethra in the region caudal to the ampullae and vesicular glands.

- The bulbourethral glands (paired) are found near the ischial arch and partially covered with skeletal mm. (urethralis/bulbospongiosus mm.).

- The urethralis muscle is a tough sphincter surrounding the urethra caudal to the prostate and is responsible for urinary continence (i.e., prevention of urine flow).

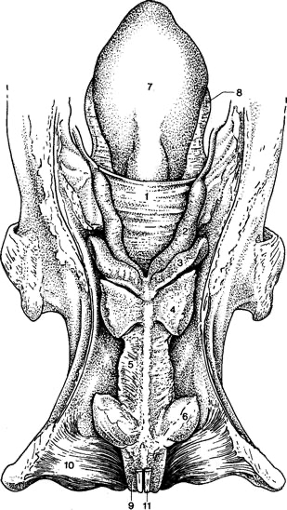

Figure 13-4 Dorsal view of the pelvic urethra and accessory reproductive glands in a stallion (in situ). 1, genital fold (blue arrow, right image); 2, ampullae of the ductus deferens; 3, vesicular glands; 4, body of the prostate gland; 5, urethralis muscle; 6, bulbourethral glands; 7, bladder; 8, lateral ligament of the bladder; 9, bulbospongiosus m.; 10, ischiocavernosus m. (covering the crus of the penis); 11, retractor penis m. TVA Ed3 22-21

Bull (Fig. 29.29, 29.33), buck/billy, ram Accessory Sex Glands

- The ampullae (aka ampullary glands) are enlargements of the wall of the distal portion of the ductus deferens (paired).

- The paired vesicular glands are lobular and adjacent to the insertion of the ampullae. They produce the majority of the seminal fluid in the BULL. These glands are more than twice as large in the BULL as they are in a STEER (castrated male ox/cattle).

- The unpaired prostate gland is ring-shaped and small in the BULL, and is not grossly visible in small RUMINANTS (i.e., it consists of only internal glandular tissue).

- The paired bulbourethral glands are small in RUMINANTS. They are found near the ischial arch and partially covered with urethralis/bulbospongiosus mm.

FIG. 29.29 Dorsal view of the bull’s pelvis and related urogenital organs. 1, Bladder; 2, genital fold; 3, right ductus deferens; 4, ampulla of deferent duct; 5, left ureter; 6, vesicular gland; 7, body of prostate; 8, urethralis (surrounding urethra); 9, bulbourethral gland; 10, bulbospongiosus; 11, caudal extent of the rectogenital pouch (broken line). TVA

Boar Accessory Sex Glands (Fig. 35.8) (a barrow is a castrated male pig)

- The paired vesicular glands are very large.

- The unpaired prostate may be hidden from view by the large vesicular glands.

- The paired bulbourethral glands are also very large. They extend cranially from the the ischial arch.

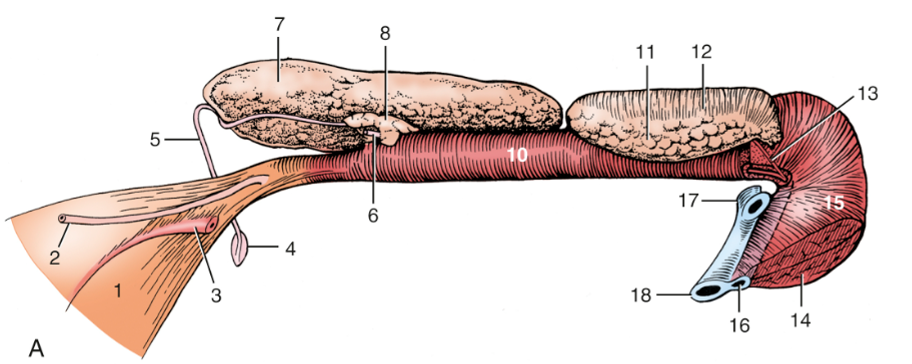

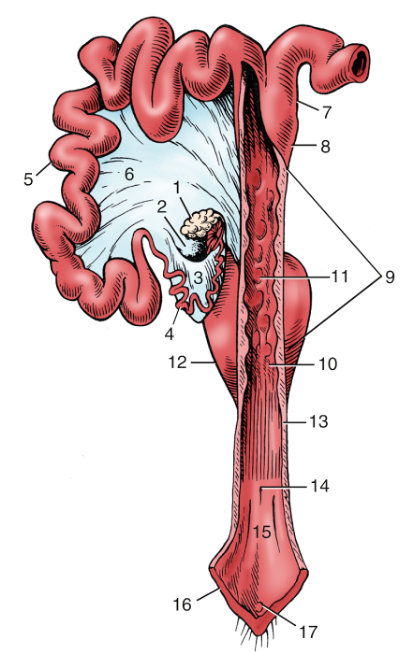

FIG. 35.8 Pelvic urethra and associated organs of (A) an 8-month-old boar, left lateral view. The left vesicular gland has been removed to expose the prostate. 1, Bladder; 2, left ureter; 3, left umbilical artery; 4, right vaginal ring; 5, right ductus deferens; 6, left ductus deferens, cut at prostate; 7, right vesicular gland; 8, body of prostate; 9, retractor penis; 10, pelvic urethra, surrounded by urethralis; 11, left bulbourethral gland; 12, bulboglandularis covering dorsal half of bulbourethral gland; 13, excretory duct of left bulbourethral gland; 14, bulbospongiosus; 15, bulb of penis; 16, penile urethra and corpus spongiosum; 17, right and left crura, cut; 18, corpus cavernosum. TVA

Objective

A9.3 Describe the general topography of prepuce, penis, extrinsic muscles of the penis, erectile tissues (with associated connective tissue), and penile urethra in ungulate species.

Basic Structures of the Penis

- The penis in the male equine, ruminant, and porcine species has internal erectile tissues (usually with the name corpus and ending in -um) and external skeletal muscles (usually ending in -sus). The extrinsic muscles of the penis (ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus mm.; skeletal mm.) surround the erectile tissues and aid in erection, generating higher pressure within the penis for ejaculation.

- In all species there is a root, body, and free part of the penis. (Figs. 5.53, ) (The distinctive features of the penis in each species will be discussed further on.)

- Root of the penis

- The most proximal part of the penis is called the root. Within the root are the right and left crura which are attached to the ischial tuberosities. Each crus is composed of corpus cavernosum penis erectile tissue surround by a dense connective tissue tunica albuginea. Each crus is covered by an ischiocavernosus m.

- The bulb of the penis is between the crura and is made up of the proximal portion of the corpus spongiosum penis erectile tissue. The bulb is covered caudally by bulbospongiosus m.

- In the horse, the bulbospongiosus m. extends most of the length of the penis.

- Body of the penis

- Once the crura join they form a common body. The body is comprised dorsally of corpus cavernosum penis erectile tissue and ventrally of corpus spongiosum penis erectile tissue and the penile urethra. The corpus spongiosum penis partially surrounds the penile urethra along the length of the penis.

- The body of the penis is surrounded by tunica albuginea.

- Free part of the penis

- The free part of the penis is the portion within the prepuce, and the glans penis is the most distal portion.

- Distally, the corpus spongiosum glandis forms the erectile tissue of the glans penis.

- The bilateral mostly smooth muscle running along the caudal and ventral aspects of the penis is the retractor penis m. (Fig. 29.33)

FIG. 5.53 Schematic drawing of the components that constitute the equine penis at its root (top) and at its apex (bottom). 1, Crus penis; 2, bulb; 3, corpus spongiosum; 4, corpus cavernosum; 5, penile urethra; 6, bladder; 7, ureter; 8, ductus deferens; 9, glans penis. TVA

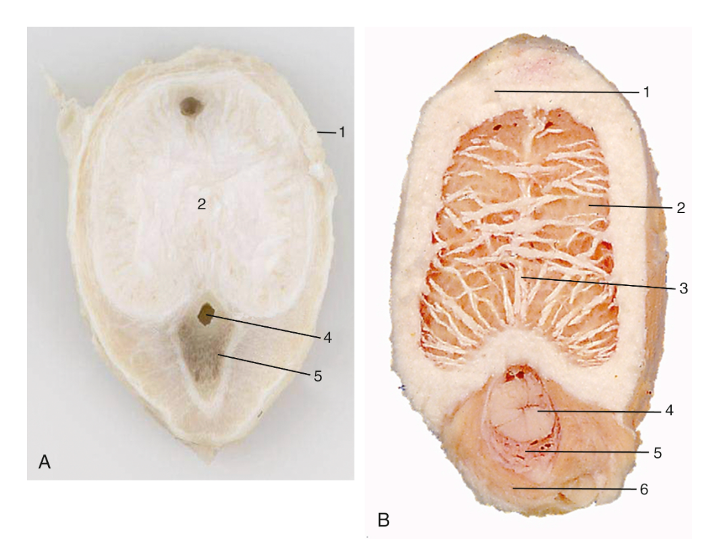

FIG. 5.54 Transverse sections of the fibroelastic penis of a bull (A) and the musculocavernous penis of a stallion (B). 1, Tunica albuginea; 2, corpus cavernosum; 3, septum; 4, penile urethra; 5, corpus spongiosum; 6, bulbospongiosus. TVA

Penile Urethra

- In all species, the penile urethra extends from the bulb of the penis to the external urethral orifice. The pelvic urethra is the portion of the urethra within the pelvic cavity.

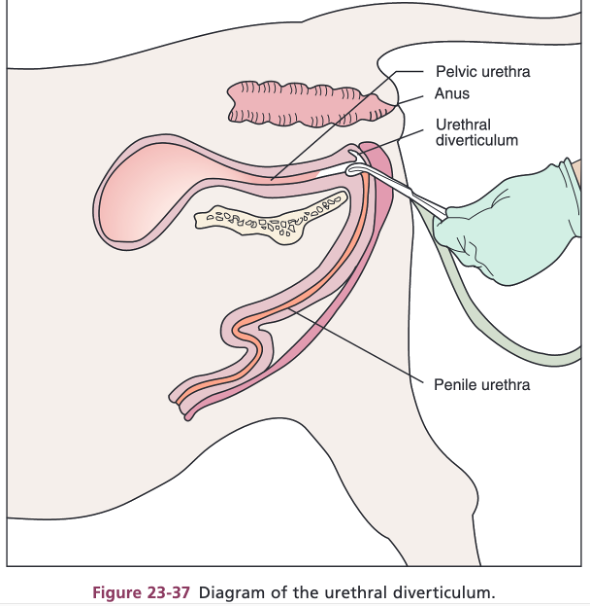

- Clinical Note: the male urethra in RUMINANTS and SWINE has a urethral diverticulum/recess (see image below, from Farm Animal Surgery) that extends from the dorsum of the urethra (intersection of the pelvic and penile urethra) at the level of the ischium. This recess can make the passage of a urinary catheter into the bladder difficult. During retrograde urethral catheterization, it almost invariably enters the recess and cannot be redirected into the bladder. To confirm that the catheter has reached the urethral recess, the surgeon can introduce a hand or finger into the animal’s rectum and palpate the catheter tip at the caudal aspect of the pelvic urethra while the catheter is gently moved back and forth. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Ruminant urolithiasis)

Figure 23-37 Diagram of the urethral diverticulum in a male bovine. Farm Animal Surgery, 2nd Ed. Fubini and Ducharme

Prepuce

- The prepuce is an external layer of skin that covers the penis. (Fig. 13-5)

- The preputial orifice is the external opening of the prepuce where the external layer (hairy skin) meets the internal layer (preputial lining).

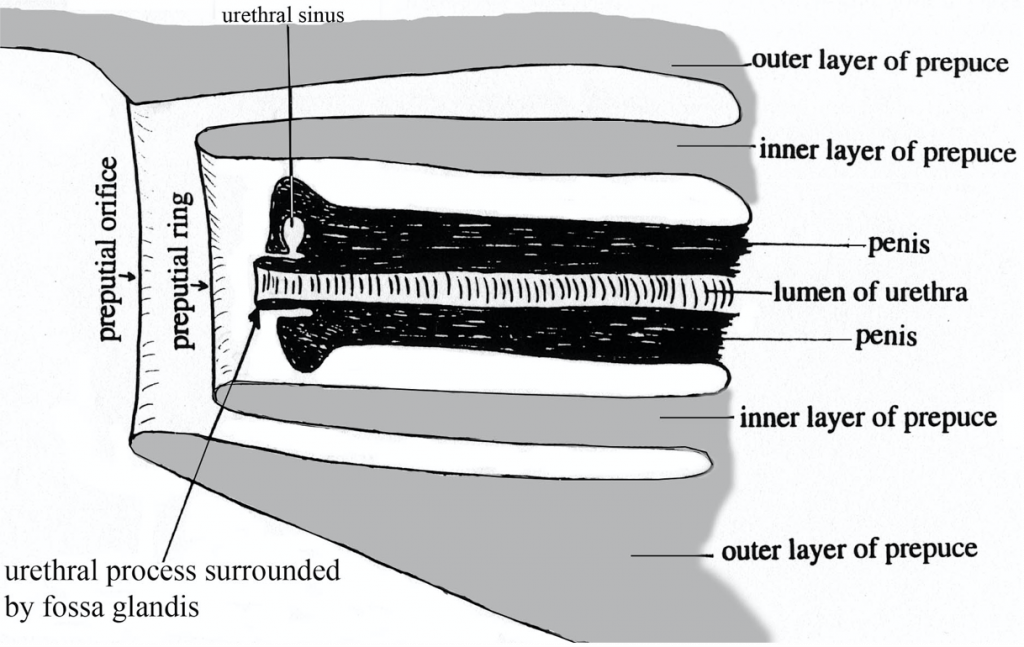

- In EQUINE, when the penis is retracted within the prepuce, the internal layer of the prepuce creates an extra fold (the preputial fold). The cranial extent of the preputial fold is the preputial ring. When the penis is erect, the preputial fold lies flat against the penis and the preputial ring appears as a raised ridge going around the penis.

Figure 13-5 Schematic median section of equine penis and prepuce. Labeled structures: outer and inner layer of prepuce, penis, lumen of urethra, urethral sinus, urethral process, fossa glandis, preputial ring, preputial orifice.

-

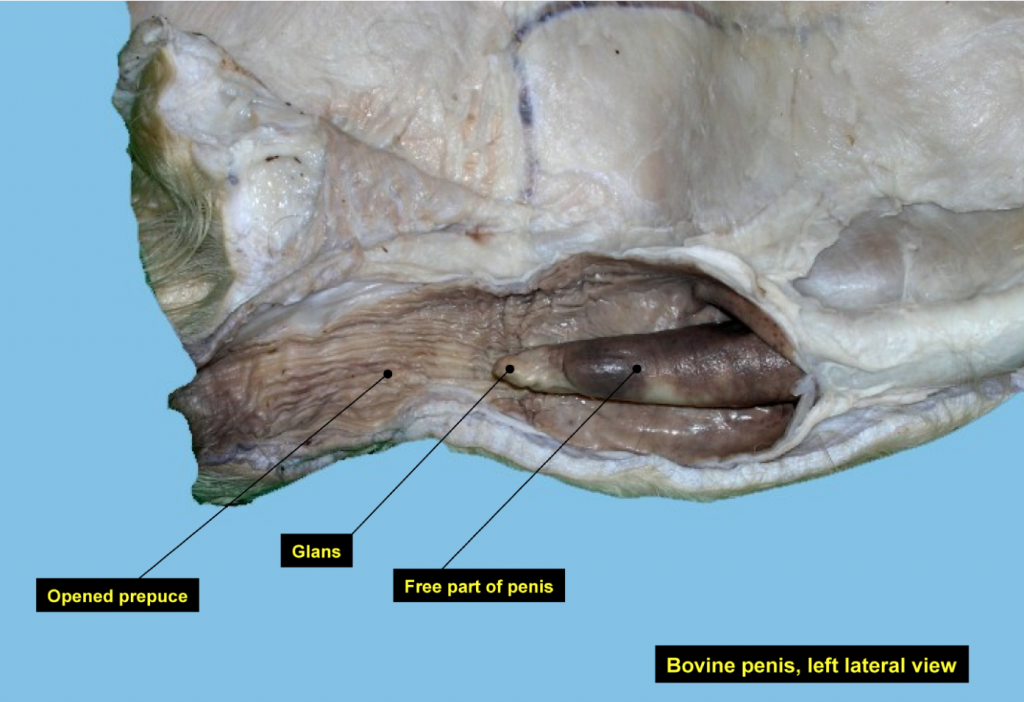

- In BOVINE and PORCINE, the prepuce is not as extensive as in the HORSE. (image of bovine below)

Figure (above) – Dissected view of opened prepuce, left lateral view in a bovine. Labeled structures: opened prepuce, glans, free part of penis. Image from slides prepared by Ray Wilhite.

Penis Structures by Species

- The male HORSE has a vascular (musculocavernous) type of penis in which erectile tissue expands the length and diameter of the penis. (see images below)

- The distal end, or glans penis, greatly expands (shaped like a ‘bell’ when engorged) and contains corpus spongiosum glandis erectile tissue.

- The urethral process (a protrusion on the tip of the penis) is surrounded by a moat called the fossa glandis.

- The urethral sinus is a dorsal diverticulum of the fossa glandis, where debris can collect and is sometimes called a ‘bean.’ This debris is hardened accumulation of smegma (secretions produced by glands in the preputial lining), and sedation is often used to remove it.

- The distal end, or glans penis, greatly expands (shaped like a ‘bell’ when engorged) and contains corpus spongiosum glandis erectile tissue.

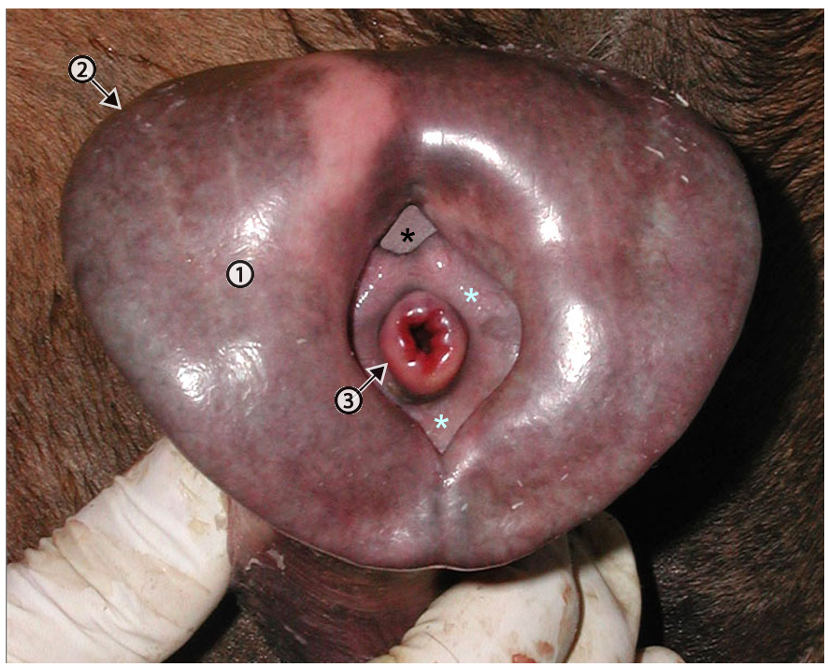

Figure above – Cranial view of fully erect equine penis. 1, glans penis; 2, corona glandis; 3, urethral process; light blue asterisks, fossa glandis; black asterisk, urethral sinus (where a “bean” is found). http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab17/Img17-10.html

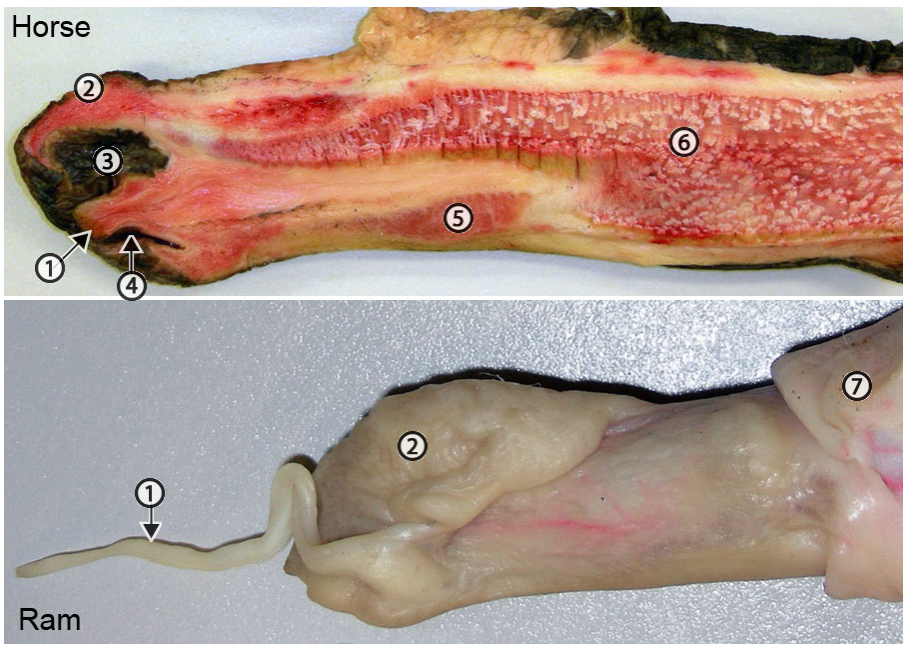

Figure above – Longitudinal section of horse penis (above). The ram penis is not sectioned (below). 1, urethral process (elongated in sheep and goat); 2, glans penis; 3, urethral sinus (where a bean is formed); 4, fossa glandis; 5, corpus spongiosum penis (continued as corpus spongiosum glandis, the erectile tissue of the glans); 6, corpus cavernosum penis (main erectile tissue of the penis); 7, preputial lining. http://vanat.cvm.umn.edu/ungDissect/Lab17/Img17-12.html

- Male RUMINANTS and the BOAR have a fibrous type of penis in which erectile tissue is within a fibrous tube and cannot expand in diameter. The erectile tissue mostly straightens out the penis, specifically at the sigmoid flexure. (e.g., bovine, porcine, small ruminant) (see image above, Fig. 29.33 below).

- In RUMINANTS and PORCINE, the body of the penis is curved into the sigmoid flexure which is composed of a proximal loop and a distal loop; the proximal loop has a smooth curvature, while the distal loop has an acute bend. The acute angle increases the likelihood that urinary calculi (i.e., urolithiasis) will get stuck.

- Note that the retractor penis m. inserts beyond the distal loop, but is free from the proximal loop.

- Clinical Notes: a common injury in breeding bulls is penile hematoma, where the tunica albuginea ruptures (and potentially vessels of the penis) near the base of the sigmoid flexure. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Penile injury)

- Clinical Notes: teaser animals are bulls that have been surgically altered to prevent pregnancy and intromission can be used to improve herd reproduction. (different procedures and related anatomy detailed in Supplemental Clinical LAS Teaser animals)

- Clinical Notes: Urolithiasis is common in goats and feedlot cattle. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Ruminant urolithiasis)

- Small ruminants (RAM, GOAT)

- The urethral process is long and narrow and can be a point where urinary calculi (i.e., urolithiasis) can get stuck.

- BULL

- The urethral process is not as long as in other ruminants and does not extend beyond the glans penis.

- In a cross sectional view of a crus, the surrounding white tunica albuginea and darker erectile tissue is sometimes called ‘pizzle eye‘ (most often seen in specimens at processing plants).

- BOAR

- The penis has a curvature which becomes corkscrew shaped when erect.

- Near the preputial orifice is the opening of the preputial diverticulum (aka ‘stink bag‘). As its name implies, it collects smelly debris. (Fig. 35.6)

- In RUMINANTS and PORCINE, the body of the penis is curved into the sigmoid flexure which is composed of a proximal loop and a distal loop; the proximal loop has a smooth curvature, while the distal loop has an acute bend. The acute angle increases the likelihood that urinary calculi (i.e., urolithiasis) will get stuck.

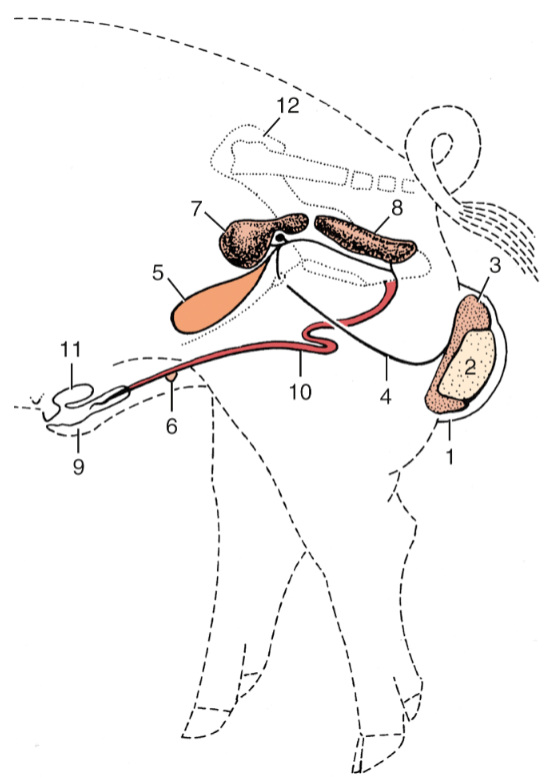

FIG. 29.33 The bovine penis and its muscles: caudolateral view. 1, Bladder; 2, ureter; 3, ductus deferens; 4, vesicular gland; 5, body of prostate; 6, urethralis; 7, bulbourethral gland; 8, ischiocavernosus; 9, crus of penis (in transverse section); 10, retractor penis; 11, bulbospongiosus; 12, sigmoid flexure, proximal and distal loops. TVA

FIG. 35.6 Reproductive organs of the boar (schematic). 1, Scrotum; 2, left testis; 3, tail of epididymis; 4, ductus deferens; 5, bladder; 6, rudimentary teat; 7, vesicular gland covering the small body of the prostate; 8, bulbourethral gland; 9, prepuce; 10, penis, proximal and distal loops; 11, preputial diverticulum; 12, right hip bone. TVA

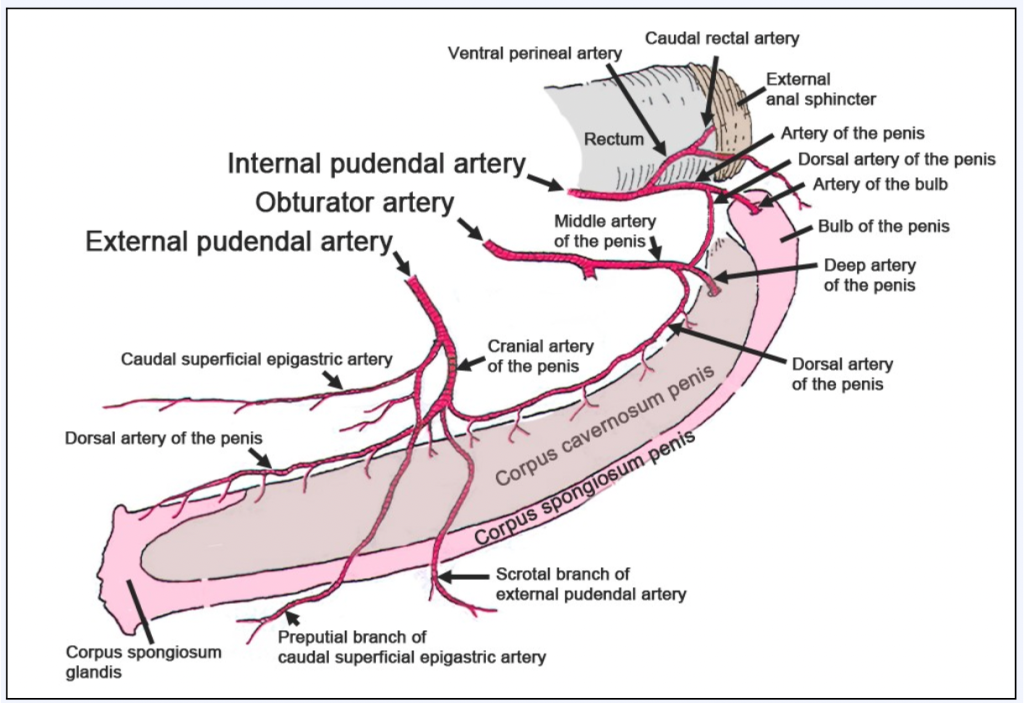

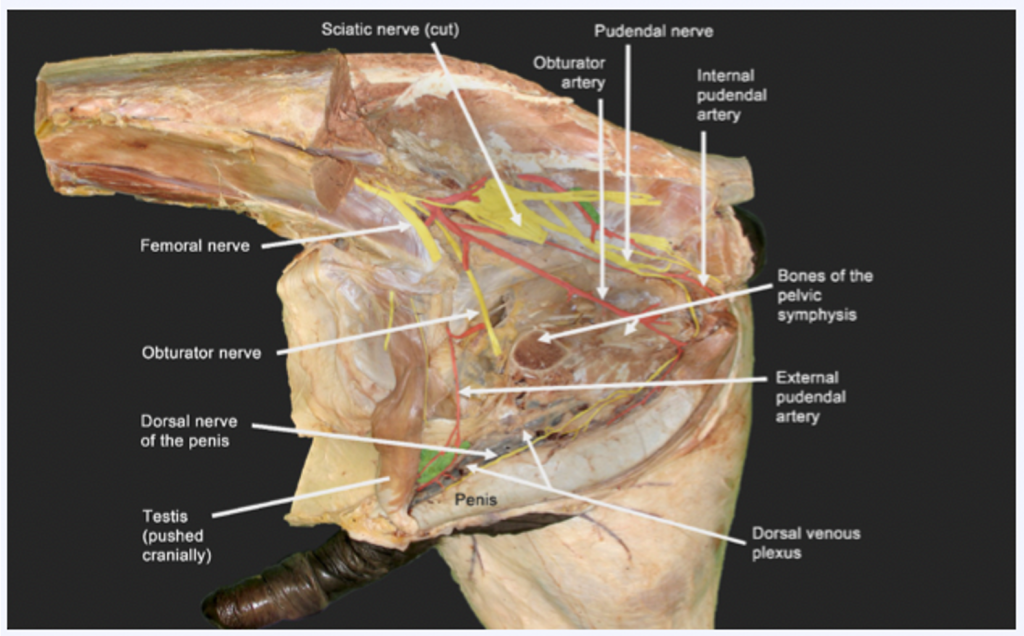

Arteries and Nerves of the Penis (Figs. 3-18a,b – figures are of equine, but other species are similar except for obturator a.)

- The internal pudendal a. eventually gives rise to the dorsal a. of the penis, which is the main blood supply for the penis, especially the corpus cavernosum and spongiosum erectile tissues. The external pudendal a. also sends branches to the penis. In the HORSE, the obturator a. also serves as a blood supply to the penis. (Fig. 3-18b) If there are issues with the patency of these vessels that supply blood to the erectile tissues, there may be erectile dysfunction.

- The pudendal n. branches into the dorsal n. of the penis, which is found along the dorsal midline of the penis. If there are lesions of these nerves, there may be erectile dysfunction.

- Clinical Notes: Pudendal nerve block – the pudendal n. innervates the rectum and internal and external genital organs (and ends as the dorsal n. of the penis/clitoris). The pudendal n. accompanies the internal pudendal a. and v. caudally along the pelvic floor and over the ischial arch. It provides motor innervation to the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani, coccygeus), the urogenital diaphragm (constrictor vestibuli and vulvae), the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus, and the external anal and urethral sphincters/urethralis (all skeletal mm.). The pudendal n. receives sensory input from the genitalia and perineal region. Parasympathetic autonomic branches accompany the ventral roots of the pudendal n. to form the pelvic nn. that enter the pelvic plexus. Sympathetic autonomic branches join the pelvic plexus from the hypogastric nerves. Autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nerve fibers from the pelvic plexus course with the pudendal n. to innervate smooth muscle in the internal anal sphincter, rectococcygeus, and retractor penis/clitoris mm. The pudendal n. can be blocked to perform various procedures on genital and perineal structures in the male and female.

Fig 3-18b: Left lateral view. Schematic showing the arterial blood supply to the equine penis. From the artery of the penis arises the artery of the bulb, deep artery of the penis, and dorsal artery of the penis. The latter 2 are small or may be absent. In their place, the deep artery receives a large anastomosis from the middle artery of the penis (obturator artery). The dorsal artery of the penis receives its major blood supply from both the middle artery and cranial artery of the penis. (from Equine Anatomy Guide: The Forelimb; Mansour, Steiss, Wilhite)

Fig 3-18a: Left lateral view showing the equine blood supply (and nerves) to the penis from the terminal branches of the external pudendal, obturator, and internal pudendal arteries from cranial to caudal, respectively. The obturator nerve runs with the obturator artery. However, in this figure, the nerve was transected and pushed cranially for better exposure. Labeled nerves: sciatic, femoral, obturator, and pudendal nerve to dorsal nerve of the penis. (from Equine Anatomy Guide: The Forelimb; Mansour, Steiss, Wilhite)

Objective

A9.4 Identify and describe the various parts of the female reproductive tract; compare/contrast the reproductive tracts of the mare, cow, and sow and identify features of clinical significance.

Ovary and Uterine Tube (Figs. 5.58, 5.55, 29.15)

- The ovaries are bilateral, round to oval in shape, and firm. They are typically positioned near the lateral body wall in the caudal region of the abdomen. There are no nerves that enter the ovary except those associated with blood vessels.

- The ovarian bursa is formed by the mesovarium (mesentery from the ovary to the body wall) and the mesosalpinx (mesentery around the uterine tube) lateral and cranial to the ovary. This bursa communicates with the peritoneal cavity.

- The mesovarium, mesosalpinx and mesometrium (mesentery along the uterine horns and body) make up the broad ligament of the uterus. (Fig. 29.15)

- The uterine tube (aka oviduct) is enveloped by the mesosalpinx from the infundibulum (the ‘funnel’ with fimbrae that catches oocytes), and courses around the cranial aspect of the ovary, to the lateral surface and then to the tip of the uterine horn. The uterine tube is thrown into a tight wave-like path by its muscular walls.

- The ovarian proper ligament is a strong fibrous band attaching the caudal pole of the ovary to the cranial end of the uterus.

- The suspensory ligament of the ovary is a thickening in the mesentery (mesovarium) attaching at the cranial pole of the ovary and leading to the body wall.

FIG. 5.58 Lateral view of the suspension of the right ovary, uterine tube, and uterine horn of a mare. 1, Ovary; 2, infundibulum of uterine tube; 3, ampulla of uterine tube; 4, isthmus of uterine tube; 5, uterine horn; 6, mesovarium; 7, mesosalpinx; 8, mesometrium; 9, arrow indicates entrance to ovarian bursa. TVA

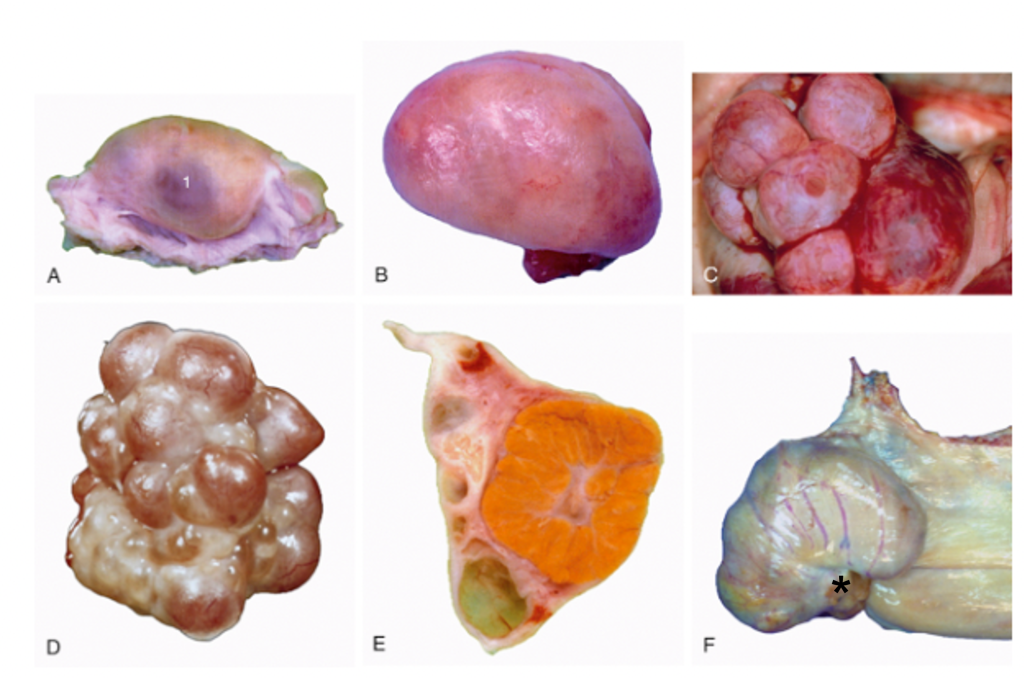

FIG. 5.55 Specific and functional variations in ovarian morphology. (A) Ovary of a cow (monotocous). 1, Mature follicle. (B) Ovary of a bitch in a quiet stage. (C) Ovary of a bitch exhibiting several mature follicles. (D) Ovary of sow (polytocous) exhibiting mature follicles. (E) Sectioned ovary of a cow containing a large corpus luteum. (F) Ovary of a mare, with ovulation fossa (asterisk). TVA, modified

- The MARE ovary is quite large and has an indentation called the ovulation fossa. This is the only site of ovulation in the mare. (Fig. 5.55 F)

- The ovary of the COW is almond shaped. The ovaries are suspended by long mesenteric ligaments from the dorsolateral wall of the abdomen, just cranial to the pelvic inlet (Fig. 29.15). The ovaries can be palpated rectally to determine cyclic activity and/or pregnancy. A pregnant uterus will be associated with a functional corpus luteum (Fig. 5.55 E); if found, the uterus should be palpated to detect a fetus.

- The ovary of the SOW has an irregular surface due to its numerous follicles. (Fig. 5.55 D)

Uterus, Cervix, Vagina (Figs. 22.8, 29.15, 29.19, 29.14, and below)

- There are variations in the uterus among ungulate species. Specifically, pay attention to the length of the uterine horns and body (a reflection of the degree of fusion of the paramesonephric ducts) and the internal irregularities associated with the cervical lumen.

- The uterus is composed of two uterine horns, a singular body and a cervix. The uterus drapes over the pelvic brim (ventral and cranial edge of the pelvis) and this can be used as a landmark to follow the uterus to the ovaries. The cervix (which is markedly firmer to the touch then the uterine body) has an external os that opens into the vagina, which joins the exit of the urinary system at the vestibule.

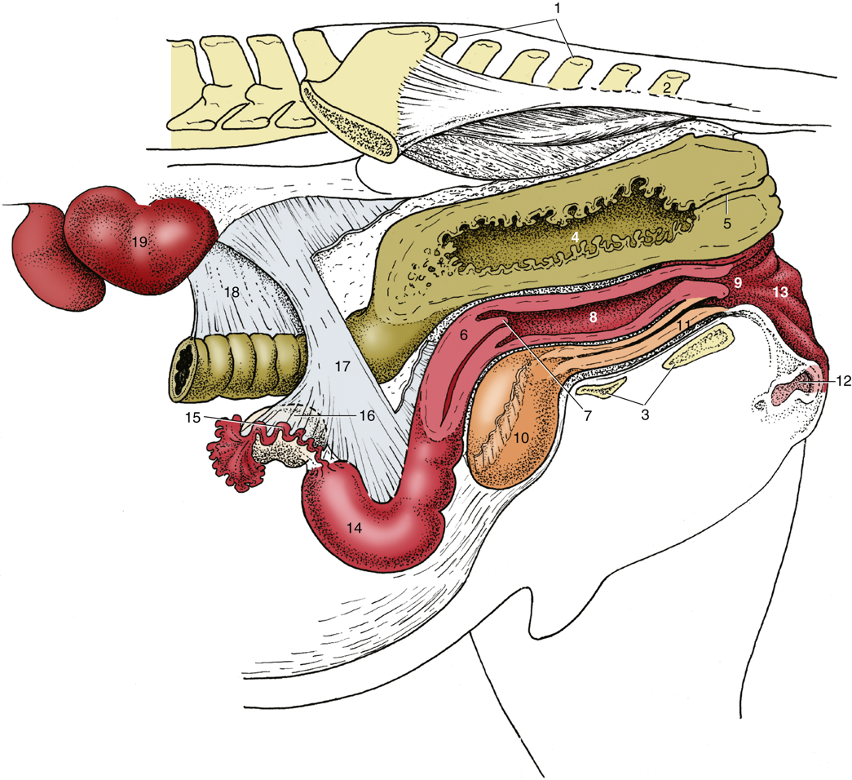

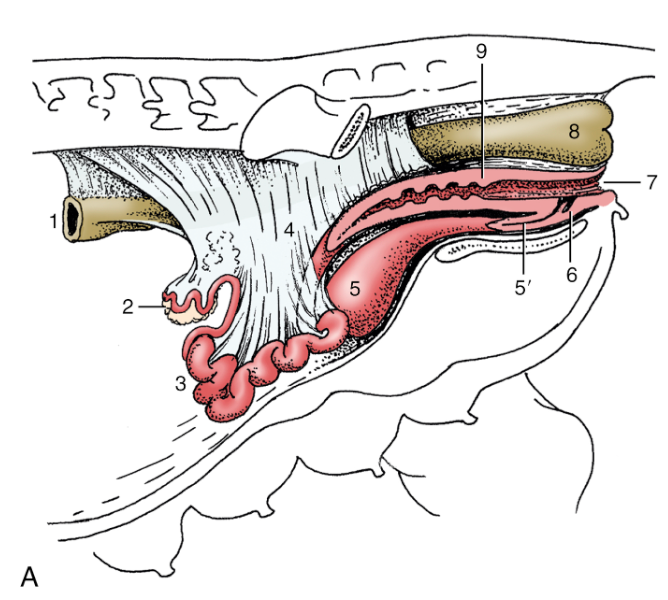

FIG. 22.8 Caudal abdominal and pelvic organs of the mare in situ; the organs have been sectioned in a paramedian plane with the pelvis. Because of the absence of the intestines, the ovaries hang much lower than they would in the intact animal. 1, Sacrum; 2, caudal vertebra 2; 3, floor of pelvis; 4, rectum; 5, anal canal; 6, cervix; 7, vaginal part of cervix; 8, vagina; 9, vestibule; 10, bladder; 11, urethra; 12, clitoris; 13, vulva; 14, left uterine horn; 15, uterine tube; 16, ovary; 17, broad ligament (largely cut away); 18, descending mesocolon; 19, left kidney. TVA

- The broad ligament of the uterus connects the uterus and ovary to the dorsal body wall, is made up of the mesometrium (supporting the uterus), mesovarium (supporting the ovary), and mesosalpinx (supporting the uterine tube). (Figs. 22.8, 29.15)

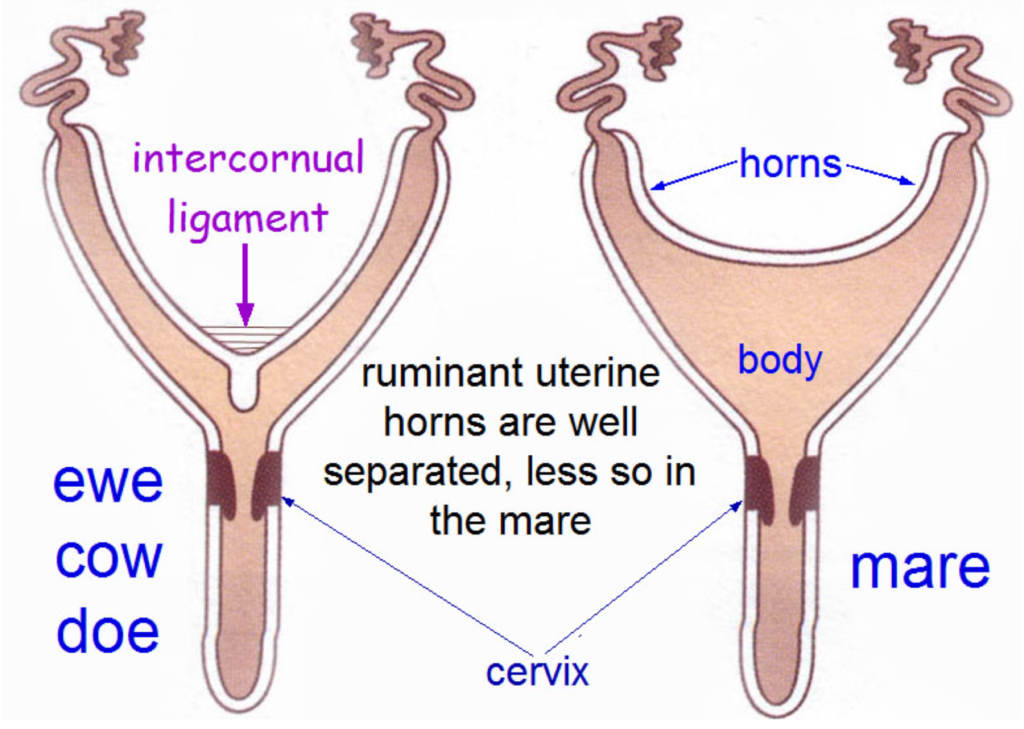

- The MARE has the greatest degree of fusion of uterine horns to form a uterine body.

- The uterus is T-shaped with no distinct intercornual ligament.

- The cervix lacks transverse folds, therefore passage of an artificial insemination (AI) pipet is relatively easy.

Figure above – Uterine body and horn differences in ruminants versus the mare. In ruminants (e.g., ewe, cow, doe), the uterine horns are well separated and have a prominent intercornual ligament between the uterine horns, and have a short uterine body. In the mare, the uterine horns are shorter, allowing for a larger/longer uterine body.

- In RUMINANTS, the uterine horns are long and coiled in a loose spiral. Fusion of the medial walls of the uterine horns causes the body of the uterus to be relatively short. (Figs. 29.14, 29.15)

- There are two intercornual ligaments connecting the uterine horns (aka cornua) of the COW. In small RUMINANTS, only one intercornual ligament is present.

- The dorsal intercornual ligament is an easily identifiable landmark in rectal palpation of the uterus in the COW. One can grab the intercornual ligaments to retract the uterus to palpate the ovaries and feel for different sized or shaped follicles on the surface. (Fig. 29.15)

- RUMINANTs have caruncles on the uterine lining (i.e., the maternal side of the placenta). The fetal component of the placenta (i.e., cotyledons) adhere to the caruncles. Each caruncle/cotyledon interface is called a placentome. There are differences in some species related to the shape of the interface (e.g., sheep have concave shape).

- Within the cervix, there are transverse folds of the cervix that make passage of an artificial insemination (AI) pipet difficult in COWs (versus MAREs).

- Clinical Note: Vaginal and uterine prolapses occur most often in dairy and beef cattle, as well as ewes. Prolapse of the uterus occurs immediately after or within several hours of parturition, when the cervix is open and the uterus lacks tone (the caruncles can be seen). (see article from Merck Veterinary Manual) Vaginal prolapses do not lead to uterine prolapses, and can be seen pre or postpartum (caruncles would not be seen). (Supplemental Clinical LAS Vaginal prolapse; LAS Pexy structures)

- There are two intercornual ligaments connecting the uterine horns (aka cornua) of the COW. In small RUMINANTS, only one intercornual ligament is present.

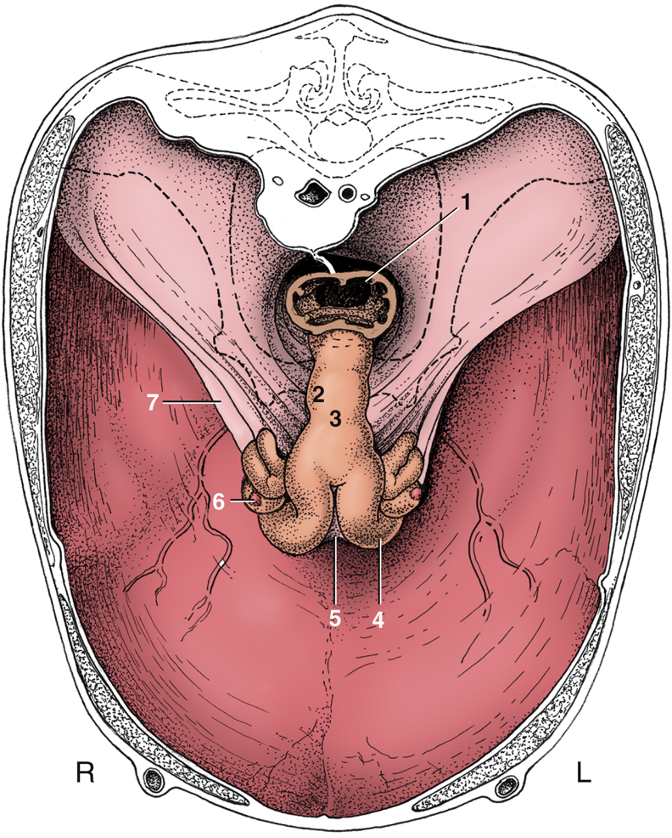

FIG. 29.15 The reproductive organs of a cow in situ, cranial view. The bony pelvis is indicated by broken lines. The uterus sags within this largely eviscerated abdomen. 1, Rectum; 2, cervix; 3, body of uterus; 4, left uterine horn; 5, (dorsal) intercornual ligament; 6, right ovary; 7, broad ligament. TVA

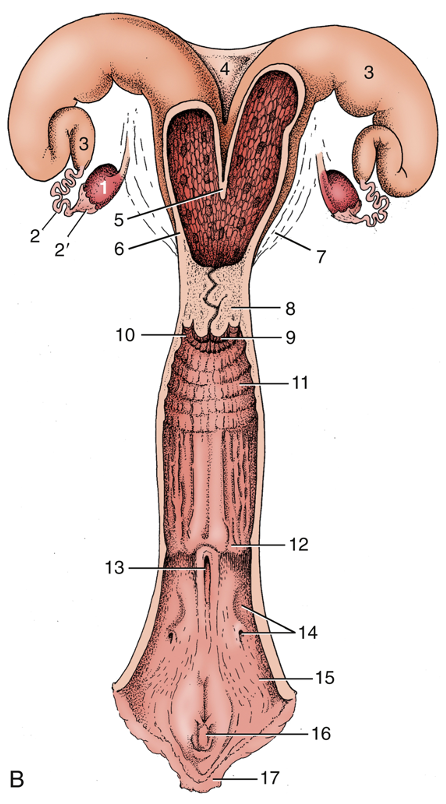

FIG. 29.14 The bovine reproductive organs, dorsal view. (B) The greater part of the tract is shown opened in the schema. 1, Ovary; 2, uterine tube; 2′, infundibulum; 3, uterine horn; 4, intercornual ligament; 5, wall of uterus dividing the two horns; 6, body of uterus with caruncles; 7, broad ligament; 8, cervix; 9, vaginal part of cervix; 10, fornix; 11, vagina; 12, position of former hymen; 13, external urethral orifice and suburethral diverticulum; 14, major vestibular gland and its excretory orifice; 15, vestibule; 16, glans of the clitoris; 17, right labium. TVA

- In the SOW, the uterine horns and cervix are relatively long. However, the uterine body is quite short. (Fig. 34.5)

- In the cervix of the SOW there are mucosal prominences, rather than transverse folds as seen in the cervix of the COW. (Fig. 35.2, 34.5)

- Uterine Blood Supply: the (middle) uterine a. is the main arterial supply to the uterus of the MARE, COW, and SOW. The satellite vein of the uterine a. is small, and instead the ovarian v. is the main drainage vessel of the uterus.

- In RUMINANTS, the ovarian a. is intimately associated with the ovarian v. so that hormones draining from their production site in the uterus can diffuse back to the ovary via the ovarian a. (e.g., to result in lysis of the corpus luteum).

-

- The genital tract receives arterial blood from three pairs of bilateral arteries (ovarian, uterine, vaginal aa.) that distribute longitudinally and connect into a single system. (Fig. 29.19)

- The ovarian a. normally arises from the abdominal aorta and courses to the ovary. The ovarian a. sends branches to the uterine tube and to the cranial end of the uterus. The ovarian a. is intimately associated with the ovarian v. The ovarian a. is small compared to the vein and has a tortuous path along the vein in RUMINANTS but not in the MARE.

- The major arterial supply to the uterus is from the uterine a. (in the COW the uterine a. arises from the umbilical a., which arises from the internal iliac a.; in the MARE the uterine a. arises from the external iliac a.). The uterine a. sends branches cranially to join the terminal distribution of the ovarian a. along the uterine horn, and caudally to join with branches of the vaginal a. In the COW, the uterine a. is palpable rectally. Changes in its size are diagnostic of the stage of pregnancy the animal is in. Uterine a. fremitus can be felt due to hypertrophy of the uterine a. and this artery travels within the broad ligament. There is a fluid turbulence that gives a ‘buzz’ feeling, or a kind of vibration to the artery.

- The genital tract receives arterial blood from three pairs of bilateral arteries (ovarian, uterine, vaginal aa.) that distribute longitudinally and connect into a single system. (Fig. 29.19)

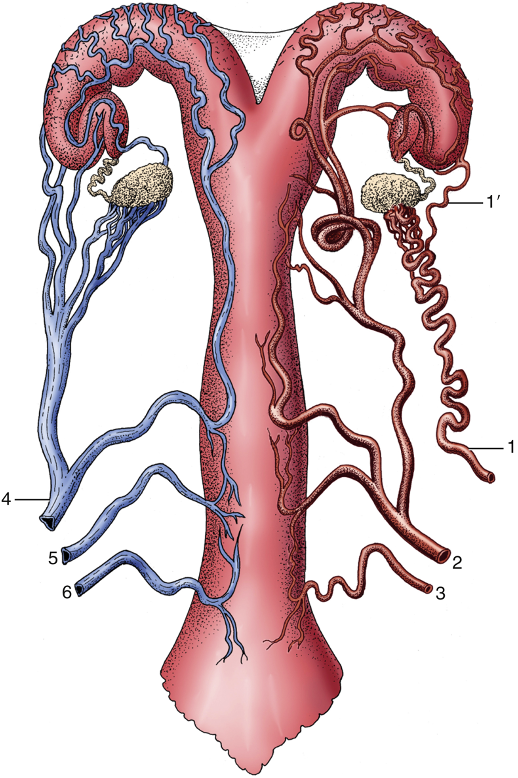

FIG. 29.19 Ventral view of the blood supply to the bovine reproductive tract (semischematic). The arteries are depicted on the right side, the veins on the left. 1, Ovarian artery; 1′, uterine branch; 2, uterine artery; 3, vaginal artery; 4, ovarian vein; 5, accessory vaginal vein; 6, vaginal vein. TVA

Vestibule (Figs. 13B-5, 29.14, 35.2)

- The vestibule is located caudal to the vagina. Urine exits the urinary bladder through the urethra via the urethral orifice into the vestibule.

- Some species (RUMINANTS, SOW) have a suburethral diverticulum ventral to the urethral orifice so there can be difficulty with insertion of urinary catheters

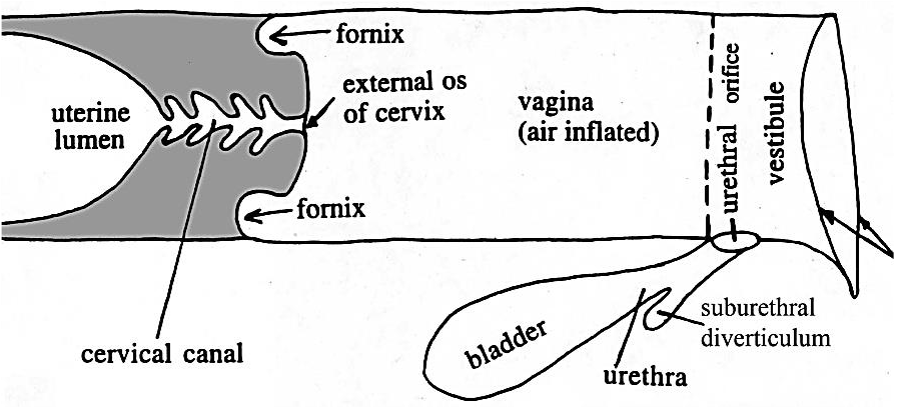

Figure 13B-5 Schematic illustration of caudal portion of a bovine female genital tract to show the location of the suburethral diverticulum. Arrows on the right = lips of vulva. Labeled structures: uterine lumen, cervical canal, fornix, external os of cervix, vagina, bladder, urethra, suburethral diverticulum, urethral orifice, vestibule.

Clitoris (FIG. 22.8, FIG. 29.14, FIG. 35.4, FIG. 22.13)

- The clitoris is in the ventral floor of the vestibule, just cranial to the vulva. The space surrounding the clitoris ventrally is the clitoral fossa.

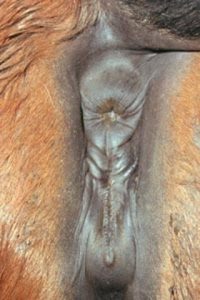

- In the MARE, at the ventral commissure of the vulva, there is a relatively large (glans) clitoris which sits in the clitoral fossa. The crura of the clitoris are deep to the mucosa of the vestibule. The clitoris is larger and more developed in the MARE than any other domestic animal. When the clitoris engorges and moves internal to external during estrus cycles, indicating sexual receptivity, this is sometimes called ‘winking.’

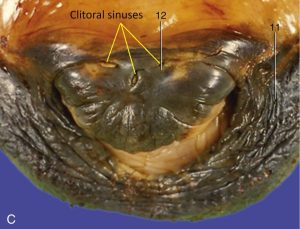

- Clitoral sinuses are depressions on the dorsal surface of the equine clitoris. There are usually at least three sinuses: one central, one towards the right, and one towards the left. (FIG. 22.13) During a breeding soundness examination, these sinuses can be swabbed for the bacteria that causes Contagious Equine Metritis.

FIG. 22.13 (C) An enlargement of the [equine] vulva, showing the glans of the clitoris within the ventral commissure. 11, Right labium; 12, glans of clitoris. TVA

Vulva (FIG. 22.8, FIG. 29.14, FIG. 35.4, FIG. 22.13)

- The vulva is made up of right and left lips or labia, which meet at the dorsal and ventral commissures (corners) of the vulva.

- The ventral commissure in the mare is rounded; whereas, it is pointed in the cow.

Photo showing the perineum in the mare. The anus is located dorsally. The vulva is shown with right and left labia/lips and dorsal and ventral commissures. http://www.equine-reproduction.com/articles/VulvalConformation.shtml

- Clinical Notes: The structural barriers or so called uterine defenses (in the MARE and COW) are the vulva, vestibular sphincter (i.e., constrictor vestibuli), and cervix. Trauma and conformational changes to these structures can cause issues with air and urine management.

- Clinical Notes: A Caslick’s suture is used in mares to treat vulvar trauma. The vulvar lips comprise the first barrier to the uterus. If the vulvar lips do not seal totally, a Caslick’s suture is placed to create the seal. A deep (thick) Caslick’s may be used as a permanent means of preventing vaginal prolapse. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Caslick’s suture)

- Clinical Notes: Other vulvar issues include splanchnoptosis (a tilt of the vulva due to drag of viscera) (Supplemental Clinical LAS Perineal anatomy) and ‘windsucking‘ (when the vulvar seal is disrupted, females develop pneumovagina and vaginitis) (Supplemental Clinical LAS Urine pooling)

- Clinical Notes: The surgical creation of a hole through the vagina to access the peritoneal cavity for ovariectomy, mummy removal and cervicopexy is called colpotomy. (Supplemental Clinical LAS Colpotomy)