10 Reimbursement Basics

Michael Finch

Introduction to Reimbursement

Reimbursement by third-party payers is a separate process from regulatory approval, although without approval there will be no reimbursement. Reimbursement is a higher bar than approval because along with proving that your device is safe and effective, you must prove that your device is cost-effective. For example, approval for reimbursement almost always requires publication of research studies in peer reviewed journals as the evidence supporting your claims about your device.

Reimbursement is essential because no patient pays for a medical device out-of-pocket but rather the cost is payed by a insurance company. Without reimbursement, the business model for your new device is not likely to be viable. Understanding the reimbursement process is complex and specialists are often hired to take the company through the reimbursement maze.

To start at the very beginning, third party payers are entities or organizations that pay for some or all of a person’s medical expenses. Government reimbursement programs include Medicare, Medicaid, TRICARE/CHAMPUS, and the Veterans Health Administration and Workers’ Compensation. Commercial or private insurance plans include Blue Cross/ Blue Shield, Prudential, Aetna, Cigna, United. WellPoint) and managed care organizations such as Kaiser, GroupHealth Cooperative and HealthPartners.

When it comes to developing a reimbursement strategy for your device, focus your time and attention on the two most powerful and influential types of third party payers in the US: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), who oversee Medicare and Medicaid, and private (commercial) payers.

Providers are those persons, institutions, facilities and firms who are eligible to provide services and supplies. Examples of providers include:

- hospitals of all types (i.e., acute care, rehab, psych, long term, specialty)

- skilled nursing facilities

- intermediate care facilities

- home health agencies

- physicians

- independent diagnostic laboratories

- independent facilities providing x-ray services

- outpatient physical, occupational, and speech pathology services

- ambulance companies

- chiropractors

- facilities providing kidney dialysis or transplant services

The reimbursement catechism says that reimbursement is a three legged stool consisting of coverage, coding and payment as shown in the following figure.

Definitions

- Coverage

- The processes and criteria used to determine whether a product, service, or procedure will be reimbursed.

- Coding

- Numeric and alpha-numeric symbols that describe the procedure performed and reason why it was performed. Used by hospitals and physicians to submit bills to insurers. Used by payers to research healthcare utilization.

- Payment

- Dollar amount reimbursed based on a specific methodology. The specific methodology varies based on type of payer and policy decisions.

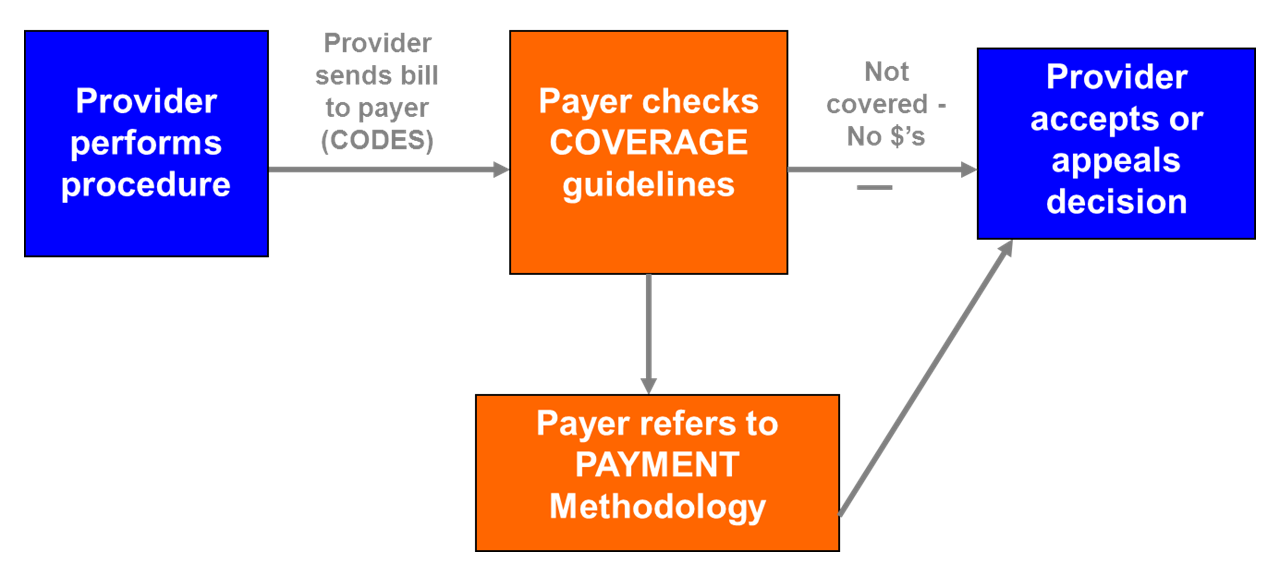

A provider, which can be an institution (such as a hospital) or a person (for instance a physician), provides some service to a patient. It may be as simple as seeing the patient in the clinic or as complex as a surgery. It may be prescribing a drug or providing diabetic education. The provider determines what services they provided, attach an appropriate code to each service and transmit these, in the form of a bill, to the third party payer.

The third party payer first checks to see if each of the services provided is a “covered service”. This is not as simple as it may sound because which services are covered and which are not varies by payer and by the specific insurance plan. Typically, payers cover services they consider “medically necessary” and deny services and technologies that are deemed “experimental and investigational”. But the definition of “medically necessary” and “experimental or investigational” varies by payer.

If the payer determines the service is not covered, the provider receives no payment for the service. If it is covered, the third party payer next determines how much it will pay for the service and passes the amount on to the provider. This is not a straight forward process as different payers use different methodologies.

In the remainder of this chapter we will discuss each leg of the stool in more detail starting with coverage, then coding then reimbursement.

Coverage

For coverage, insurance companies want the evidence of clinical benefit, cost and utilization to come from peer-reviewed articles in credible medical journals, a review of available studies on a particular topic, evidence-based consensus statements by practitioner organizations, expert opinions of health care professionals and guidelines from nationally recognized health care organizations. In short, they are looking for evidence and not just the company saying the product is wonderful.

More to the point, insurance companies are looking for:

- Final approval from the appropriate government regulatory bodies.

- Scientific evidence that supports conclusions concerning the effectiveness of the technology on health outcomes.

- Technology that improves the net health outcome.

- Technology that is as beneficial as established alternatives.

- Improvement that is attainable not just in experimental and investigational settings.

- Evidence that the new technology is better than the current standard of care.

- Credible estimates of the cost of the new approach compared to the current practice and evidence that any extra cost is justified by the gain in quality or clinical outcomes.

- Consensus on when the new treatment be used, including patient selection criteria.

Medicare

The most powerful and influential entity in the coverage process is Medicare. Given the size and scope of Medicare, the coverage process is often critical to the survival of a new technology. More often than not, commercial insurers follow Medicare’s lead in developing their coverage polices. If Medicare does not cover a new technology, it will be an uphill effort to obtain coverage from commercial payors.

In order for Medicare to cover and pay for an item or service, it must be medically necessary and meet the reasonable and necessary” requirement “… the Social Security Act provides that Medicare may not pay for expenses of items and services that are not reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis and treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member. § 1862(a)(1)(A).”

The American Medical Association Model Managed Care Contract, frequently accepted by commercial insurers, suggests the following definition of medically necessary: “Health care services or procedures that a prudent physician would provide to a patient for the purpose of preventing, diagnosing or treating an illness, injury, disease or its symptoms in a manner that is (a) in accordance with generally accepted standards of medical practice; (b) clinically appropriate in terms of type, frequency, extent, site and duration; and (c) not primarily for the economic benefit of the health plans and purchasers or for the convenience of the patient, treating physician or other health care provider.”

Medicare coverage decisions can be either nationwide (NCD) or local (LCD). (For reference, only about 20-30 national coverage decisions are made each year). To find if a service is covered by Medicare go to the CMS.gov indexes. [1] NCDs, which are updated in real time, and LCD, which are updated weekly, provide information on numerous Medicare covered and not covered services and procedures.

Medicare will often deny coverage to new technologies because the research is lacking, inconsistent or insufficiently persuasive. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) for Chronic Low Back Pain is an example. Those attempting to garner Medicare coverage are advised to review the Medicare’s solution to this interesting case at the CMS site. [2] In this case Medicare responded: “TENS is not reasonable and necessary for the treatment of CLBP under section 1862(a)(1)(A) of the Act.”

However, in their own words, “In order to support additional research on the use of TENS for CLBP, we will cover this item under section 1862(a)(1)(E) of the Social Security Act (the Act) subject to all of the following conditions:

- Coverage under this section expires three years after the publication of this decision on the CMS website.

- The beneficiary is enrolled in an approved clinical study meeting all of the requirements below. The study must address one or more aspects of the following questions in a randomized, controlled design using validated and reliable instruments. This can include randomized crossover designs when the impact of prior TENS use is appropriately accounted for in the study protocol.

- Does the use of TENS provide clinically meaningful reduction in pain in Medicare beneficiaries with CLBP?

- Does the use of TENS provide a clinically meaningful improvement of function in Medicare beneficiaries with CLBP?

- Does the use of TENS impact the utilization of other medical treatments or services used in the medical management of CLBP?”

Exceptions such as these are uncommon. Take, for instance, the CMS coverage decision for acupuncture:

Indications and Limitations of Coverage

Although acupuncture has been used for thousands of years in China and for decades in parts of Europe, it is a new agent of unknown use and efficacy in the United States. Even in those areas of the world where it has been widely used, its mechanism is not known. Three units of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, and Fogarty International Center have been designed to assess and identify specific opportunities and needs for research attending the use of acupuncture for surgical anesthesia and relief of chronic pain. Until the pending scientific assessment of the technique has been completed and its efficacy has been established, Medicare reimbursement for acupuncture, as an anesthetic or as an analgesic or for other therapeutic purposes, may not be made. Accordingly, acupuncture is not considered reasonable and necessary within the meaning of §1862(a)(1) of the Act.’

Other Insurers

After examining the Medicare site, the innovator should explore the coverage policies for the major commercial insures. UnitedHealth [3], Cigna [4] and Aetna [5] are among the largest insurers and each lists coverage polices on their web pages, which are free, easy to navigate and will give you an excellent view of what is covered as well as why a device, procedure or treatment might not be covered. Aetna’s policy bulletins are particularly useful as they provide extensive discussion of how Aetna reached their decision and the citations to the literature upon which they relied.

Two other sources can be consulted as they both provided detailed responses to the basic question asked by the insurers. The first are the evaluations performed by Blue Cross Blue Shield Technology Evaluation Center. [6] The second is the California Health Benefits Review Program (CHBEP), [7] which also publishes reviews of medical technology effectiveness. While CHBEP examines a limited number of technologies they categorize the strength of the evidence that form their conclusions.

Codes

Codes are the second leg of our three legged stool. You may have coverage, but now you need a code. Codes are the language spoken by payers. Without a code you have no way to speak to a payer and no way to get paid. Each year, in the US, health care insurers process over five billion claims for payment. Standardized coding systems are essential to ensure that these claims are processed in an orderly and consistent manner.

For example, a first check in your reimbursement strategy should be to determine if there is an existing procedure code that covers the proposed new device or service. The codes are used by clinicians when billing for services. For example ICD-9-CM codes are used for inpatient procedures while CPT codes are used for outpatient expenses. A second check is to see if the standard third-party payors (e.g. Medicare or BlueCross) reimburse for that code. A full reimbursement strategy checks for these and other challenges for receiving payment.

The two things you need to know about codes are when to use which codes and how to get a code if one is not already in place.

The list of relevant code sets is:

- ICD diagnosis codes

- ICD procedure codes

- CPT codes

- HCPCS codes

- DRG codes

The remainder of this section describes each coding system and who uses it. This is important as different code sets are used depending on where the service or product is provided.

ICD Diagnosis Codes

ICD is industry shorthand for the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, or for short the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The ICD codes are owned by the World Health Organization and are modified by member states to meet their needs. For example, ICD-10 has about 14,000 codes and provides a system for classifying diseases. The individual codes enable nuanced classifications of a wide variety of signs, symptoms, abnormal findings, complaints, social circumstances, and external causes of injury or disease.

The ICD is periodically revised with ICD-9 released in 1975, ICD-10 in 1994, and ICD-11 in 2022. Modifications of the first two are used in the United States with the USA version of ICD-11 expected to start in 2027.

ICD-CM Procedure Codes

The USA version of the ICD codes is The International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification, referred to as ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM, and was created by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics to be used in assigning diagnostic and procedure codes associated with inpatient, outpatient, and physician office utilization in the United States. The National Centers for Health Statistics and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are the U.S. governmental agencies responsible for overseeing all changes and modifications to the ICD-x-CM. ICD-9-CM has about 13,000 codes and ICD-10-CM about 68,000. When developing a new medical technology, it is prudent to examine both ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes.

ICD-9-CM codes can be found at the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [8] Also, Wikepedia has a good list of diagnostic codes [9] and procedure codes.[10]

CPT Codes

Current Procedural Technology (CPT) codes, are owned and maintained by the American Medical Association. Originally focused on surgical procedures, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA, now known as CMS), adopted CPT codes for reporting physician services for Medicare Part B Benefits and for reporting outpatient surgical procedures.

CPT codes are divided into three categories:

- Category I

- Category I codes are assigned to procedures that are deemed to be within the scope of medical practice across the US. In general, such codes report services whose effectiveness is well supported in the medical literature and whose constituent parts have received clearance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- Category II

- Category II codes are tracking codes designed for the measurement of performance improvement. The concept is that the use of these codes should facilitate the administration of quality improvement projects by allowing for standardized reporting that captures the performance of services designated as subject to process improvement efforts.

- Category III

- Category III codes are temporary codes for new or emerging technology or procedures. Such codes are important for data collection and serve to support the inclusion of new or emergency technology in standard medical practice.

The AMA provides the following guidance for seeking a Category I code.

A proposal for a new or revised Category I code must satisfy all of the following criteria:

- All devices and drugs necessary for performance of the procedure or service have received FDA clearance or approval when such is required for performance of the procedure or service.

- The procedure or service is performed by many physicians or other qualified health care professionals across the United States.

- The procedure or service is performed with frequency consistent with the intended clinical use (i.e., a service for a common condition should have high volume, whereas a service commonly performed for a rare condition may have low volume).

- The procedure or service is consistent with current medical practice.

- The clinical efficacy of the procedure or service is documented in literature that meets the requirements set forth in the CPT code change application.

It is useful to understand how new CPT codes come into existence. The AMA CPT Editorial Panel maintains CPT and consists of eleven physicians nominated by the National Medical Specialty Societies, one nominated by the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, one nominated by America’s Health Insurance Plans, one nominated by the American Hospital Association, and one nominated by CMS. The CPT Advisory Committee is supported by the CPT Editorial Panel and consists of physicians nominated by national medical societies that are part of the AMA House of Delegates.

Proposals for a new code go through the following steps:

- A specialty society develops an initial proposal. Typically, the specialty society will be most familiar with trends shaping a specific specialty and can represent important trends driven by technology and changing practice patterns.

- AMA Staff reviews the code proposal. This preparatory step confirms that the issue has not been previously addressed and that all of the documentation is in place.

- The CPT Specialty Advisory Panel then reviews the code proposal. Their comments are then shared with all participants in the process, but not with the general public.

- The CPT Editorial Panel then reviews the code proposal at its regularly scheduled meeting. The group can approve the code, table the proposal, or reject the proposal.

- Approved Category 1 codes are then submitted to the Relative Value Scale Update Committee who assigns relative value units (RVUs) for all Category 1 CPT codes.

The last step is important as a new code does not always result in a payment; there are numerous codes assigned a zero payment.

All CPT Category III codes are removed after five years from the time of publication. If the original requesters of the code want to continue use of the code, they must submit a proposal for continuing the code or promoting it to Category I.

HCPCS Codes

The Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System was developed by HCFA (now CMS) to cover a variety of services, supplies, and equipment that are not identified by CPT codes. These are called Level II HCPCS codes. Since 2003, there have been two levels of HCPCS. Level I include the standard CPT codes and Level II include non-physician services such as ambulance services and prosthetic devices, and items and supplies and non-physician services not covered by CPT codes.

DRG Codes

Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) are a means of classifying patients likely to need a similar level of hospital resources for their care and are an effort to quantify hospital care. Each patient discharged from a hospital is assigned a single DRG and each DRG code was designed to represent “medically meaningful” groups of patients. Thus, all patients in the same DRG are expected to display a set of clinical responses which will, on average, result in equal use of hospital resources.

Four guiding principles were established when the DRG system was formed:

- The patient characteristics used in the DRG definition should be limited to information routinely collected on the hospital billing form.

- There should be a manageable number of DRGs that encompass all patients seen on an inpatient basis.

- Each DRG should contain patients with a similar pattern of resource intensity.

- Each DRG should contain patients who are similar from a clinical perspective (i.e., each class should be clinically coherent).

Each DRG is assigned a weight that indicates its relative cost as compared with all other DRGs. That weight is then adjusted based on a hospital’s geographic location, whether or not it is a teaching hospital, the percentage of low-income patients in the group,and whether a particular case is unusually costly. This weighting is used to calculate the payment rate for that DRG.

Prior to DRGs, payments to hospitals were based on the hospital’s reported costs which could be arbitrary and unpredictable. By assigning each patient to a specific DRG, the onus was placed on the hospital to work within a more predictable and structured reimbursement system, allowing for a more accurate determination of the type of resources needed to treat a particular group and to predict more closely the cost of that treatment.

The current DRG system, started in 2007, is called the Medicare Severity DRGs (MS-DRGs). MS-DRGs have a three-tiered structure: 1) major complication/comorbidity (MCC), 2) complication/comorbidity (CC), and 3)no complication/comorbidity (non-CC). MCCs reflect secondary diagnoses of the highest level of severity. CCs reflect secondary diagnoses of the next lower level of severity. Secondary diagnoses which are not MCCs or CCs (the non-CCs) are diagnoses that do not significantly affect severity of illness or resource use. There are 745 MS-DRG, which can be found on the CMS website. [11]

Recognizing that over time, changes in technology and technique could affect its payment rate, CMS annually reviews data it has collected regarding the costs of the procedures in each of its DRGs and recalibrates the relative payment rates for the DRGs accordingly.

Payment

Now that you have coverage and a code, you must determine the likely reimbursement for your device, keeping in mind that the reimbursement amount will depend on the location where a service or product is provided. For Medicare, which is where you will find the best information on reimbursement, many procedures have separate rates for physicians’ services based on whether they were provided in a facility or a non-facility settings. What all this means is that, while very tedious, you need to know the places where your product or service will be provided and the appropriate Place of Service codes (POS).

A device may be used in an institution. Institutions include, for example, hospitals, nursing facilities, some outpatient rehabilitation clinics, and community health centers, to name a few. Here, the institution will be submitting a UB-04 form to the payer and the pertinent codes will be ICD diagnosis or procedures codes.

If the device is used outside of an institution, for example, in a clinic or at home, a request for reimbursement will be made on a CMS-1500 form using CPT or HCPCS codes. This covers services provided by health care professionals (called professional services, which can also have a technical component attached) and suppliers of durable medical equipment. It can get tricky as professional services are paid at two rates depending on whether the service was performed in a facility or in a non-facility. A full list of place of service codes is on the CMS website. [12]

Non-facility rates are applicable to outpatient rehabilitative therapy procedures and all comprehensive outpatient rehabilitative facility (CORF) services, regardless of whether they are furnished in facility or non-facility settings.

Reimbursement for Professional Services and Durable Medical Equipment

For reimbursement for CPT and HCPCS codes, the first place to search is CMS’s Part B National Summary Data File. [13] This file is useful in determining the number of times each code was reimbursed during a given year, the actual payment from Medicare and the amount billed amount, the amount the provider of the service asked to be paid. As a rule the actual payment is always less than then the requested reimbursement. However, the requested reimbursement is of value as it is often closer to actual payment provided by commercial insurers. Along with the data file there is a readme file that explains how to use the data files and the meaning of the modifier codes. Modifier codes are important because they may affect the reimbursement that you can expect.

The Part B National Summary Data File has several major advantages over other sources. First, Medicare is the only health insurance that publishes the amount they will pay and what they have paid for different services. Commercial firms religiously guard this information and though it is possible to purchase their data, it is expensive and often geographically limited. Second, the file contains, for each CPT and HCPCS code, on an annual basis, the number of times the code use used, the maximum amount Medicare will pay (called the ALLOWED AMOUNT) and the amount Medicare actually paid for these services/devices (called the PAID AMOUNT). Third, you can find historical data going back to 2000. Fourth, the file has data on Medicare’s covered population, which is huge. Fifth, most commercial payers use Medicare payments rates as a starting point for their own payments.

The file also has two drawbacks. First, the file is limited to Medicare Fee-For-Service Part B Physician/Supplier data and does not include information for services provided in the managed care portion of the program (called Medicare Advantage). Second, the file is typically two years out of date.

The second place to look for reimbursement rates is the CMS Physician Fee Schedule. [14]

This site provides both facility and non-facility Medicare reimbursement for all CPT and HCPCS codes. An advantage of this site is that it gives the actual payment rather than just the components of the payment, which typically change every year. Be sure to read the associated documentation as there are several options which are not immediately intuitive, such as national payment amount or local amounts.

Reimbursement for Institutional Services

A common thread in reimbursement of services provided in institutions is the move by payers to prospective payment. In a prospective payment system (PPS), reimbursement is established before services are provided. Various systems are used to assign a payment to a code and then a code to a patient. The most notable is the DRG system.

The move to a prospective system was made in response to the rising cost of health care, driven primarily by acute care hospitals. Implemented in 1983, the hospital prospective payment system assigned every patient to a specific DRG based on the diagnosis and treatment. Each DRG was reimbursed at a single rate. Thus, with some specific exceptions, no matter the extent of services provided to different the patients, the hospital received the same payment for each.

The success of PPS in holding down the increase in payments paid to hospital has spurred CMS to instituted prospective payment systems to other areas, including rehabilitation and psychiatric hospitals, skilled nursing homes and home health as well as to ambulatory surgical centers and hospital outpatient services.

Medicare pays for hospice on a per diem rate for each of four levels of care: Routine Home Care, Continuous Home Care, Inpatient Respite Care, General Inpatient Care. Medicaid and commercial insurers have generally followed the lead of CMS and pay for these same services on a prospective basis. Several years ago it was not uncommon for commercial insures to pay per diem payments (i.e. a fixed amount for each day a patient is in the hospital). However, the entire industry has quickly moved to more and more emphasis on a prospective approach.

The relevant file to read is the CMS Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Inpatient. [15] This file contains, for over 3,000 hospitals in the US, the number of discharges, average charges and average payment, for the top 100 DRGs (which account for over 60% of all Medicare hospitalizations).

Another valuable source is the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), which collects encounter-level information from hospitals regardless of payer (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, uninsured). This includes ICD-diagnoses and procedures codes, discharge status, patient demographics, charges, and cost based on a cost-charge ratio developed by CMP. The HCUP national files [16] contain data on about 7 million hospital stays each year, but based on statistical weighting, represents over 36 million hospitalizations nationally. Separate files are available for pediatric populations and emergency departments and ambulatory surgeries. H-CUPnet is easy to use and can be searched by specific ICD diagnosis and procedure codes as well as DRG. These can be sorted by age, sex, payer (Medicare, Medicaid or commercial) and geography. It can also provide trend data for any of these selections.

The Future

Health care reimbursement is constantly undergoing change, and the rate of change has increased dramatically since the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. The good news is that CMS’s new technology add-on payment is still in force and provides additional payments for inpatient cases with high costs involving eligible new technologies. The additional payment is based on the cost to hospitals for the new technology. However, the Medicare payment is limited to the DRG payment plus 50 percent of the estimated costs of the new technology.

Medicare has changed the approval of reimbursement from local determination to national determination. Since 2003, Medicare allowed payment for the routine costs of care furnished to Medicare beneficiaries in certain categories of Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) studies. However, the coverage was at the local level. Effective January 1, 2015 all technology add-on payment requests will be reviewed and approval at the national level.

You are advised to pay close attention to a number of developments. First is the momentum behind comparative effectiveness. Comparative effectiveness is the direct comparison of health care interventions to determine which work best for which patients and which pose the greatest benefits and harms. Over one billion dollars were set aside from the 2009 stimulus package for comparative effectiveness research in the health care arena.

While this may sound non-threating to a new product, it is just the opposite. The move behind comparative effectiveness is better technology at a lower price. CMS has been vocal about not paying for me-too technologies. At their February 2015 New Technology Town Meeting they reiterated their position that, “Section 412.87(b)(1) of our existing regulations provides that a new technology will be an appropriate candidate for an additional payment when it represents an advance in medical technology that substantially improves, relative to technologies previously available, the diagnosis or treatment …”. Commercial payers have been echoing the same sentiment.

Second is the move to increase the share of financial risk facing providers. One approach to sharing financial risk is to bundle acute care episodes. A bundled payment is a single payment to providers or health care facilities or both for all services to treat a given condition or treatment as well as costs associated with preventable complications. Another approach is Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), where groups of providers would assume more, if not all the financial risk of caring for patients. Under these scenarios, providers could receive a single capitated payment for each person on their ACO or, at a minimum, take on a substantial portion of the risk. In January 2015, Modern Health Care reported that, “…HHS pledged that half of Medicare spending outside of managed care—roughly $360 billion last year—would be funneled through accountable care and other new payment arrangements by 2018. Separately, mid-March of 2015, a coalition of health systems, insurers and employers including Trinity and Aetna, called the Health Care Transformation Task Force, vowed that 75% of their business would be tied to new financial incentives by 2020.”

What this means is that your new technology will need to be both better and less expensive. Premium pricing will be difficult to negotiate and second to market me-too technologies will need to compete on price.

Coverage will remain critically important, but will be based more and more on the ability of the technology to create true value either through better pricing or better performance or, preferably, both. Codes will continue to be the coin of the realm but the transition to ICD-10 will be tenuous and will need to be carefully navigated.

In the past reimbursement was a tedious and time consuming process. In the future, it will require analytic and rhetorical skills to prove that a new technology is worthy of reimbursement.

- cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/reports/reports.aspx# ↵

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) for Chronic Low Back Pain, http://goo.gl/Hm18o7 ↵

- United Health, Resources for Providers, http://goo.gl/0fvaa ↵

- Cigna, Resources, http://goo.gl/9ER169 ↵

- Aetna, https://www.aetna.com/health-care-professionals/clinical-policy-bulletins/medical-clinical-policy-bulletins.html ↵

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massashusetts, Medical Technology Assessment Guidelines (link) ↵

- https://chbrp.org/completed_analyses/index.php ↵

- ICD-9-CM Diagnosis and Procedure Codes, www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD9ProviderDiagnosticCodes/codes ↵

- Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ICD-9_codes ↵

- Wikipedia, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ICD-9-CM_Volume_3 ↵

- www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/MS-DRG-Classifications-and-Software ↵

- www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/Website-POS-database.pdf ↵

- www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Downloadable-Public-Use-Files/Part-B-National-Summary-Data-File/Overview ↵

- www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search/overview ↵

- data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-inpatient-hospitals ↵

- hcupnet.ahrq.gov/ ↵