16 Clinical Trials

Jenna Iaizzo and Paul Iaizzo

Introduction

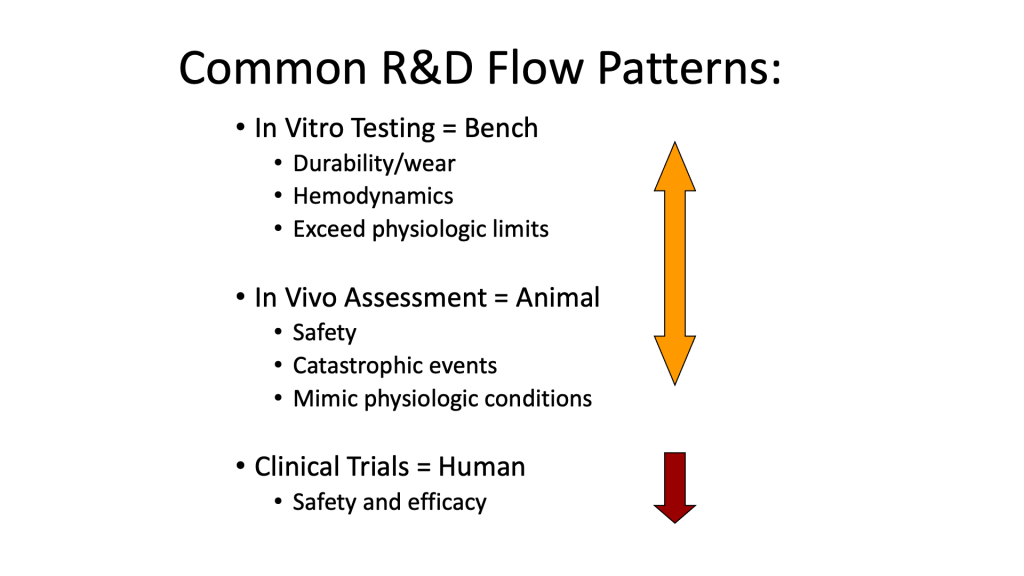

Clinical trials are a necessary step in the medical device innovation process and are the only way that the developer can determine how the device will perform in the human body or when used by humans. A clinical trial provides valid scientific evidence on the safety and efficacy of a device, which can be used when submitting to a regulatory body for approval to market or to a third party payer when making the case for reimbursement. If the technology, therapy or device is novel, it will take experienced individuals or teams to design well planned clinical trials, which could be internal experts within your company or outside experts. Such individuals should fully understand the pre-clinical outcomes.

Prior to your clinical trials, one should have confidence in the technologies and a design freeze has been made with certainty.

Early clinical testing, sometimes called first-in-human (FIH) tests, are studies with a small number of subjects (one to 10) to do initial validation of the device in humans. Larger validation studies can involve hundreds of subjects and multiple trial sites around the country or around the world. Any clinical study requires clearly defined objectives, a repeatable protocol, appropriate statistics to analyze results and honest interpretation of the data. Startups and established med-tech companies often contract with universities to conduct early stage clinical research and to assist with full-blown clinical trials.

All research using human subjects requires examination and approval by a local Institutional Review Board (IRB) in the United States, whose counterpart in other countries is the Ethics Committee. The role of the IRB is to determine that the protocol is appropriate, the benefits of the study outweigh the risks, investigators are qualified and trained in the principles of research involving human subjects, subject participation in voluntary and principles of informed consent will be followed. Most research universities have a local IRB with extensive guidance to investigators on local requirements and protocol submission and approval process.

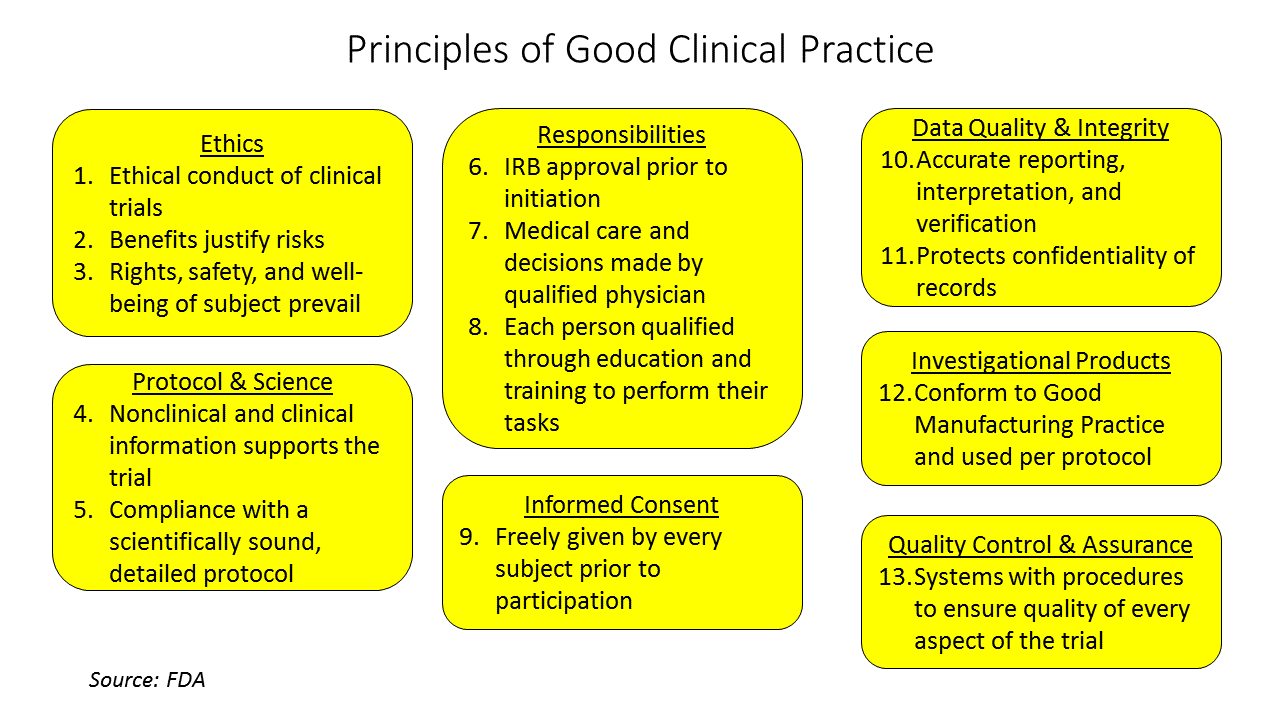

Good Clinical Practice

The FDA defines what is known has Good Clinical Practice (GCP), a set of principles that should and must be followed for any clinical study that will be used as evidence for regulatory approval. GCP is the standard for the design, conduct, performance, monitoring, auditing, recording, analysis and reporting of clinical studies. GCP is intended to protect the rights, safety and welfare of human subjects, to assure the quality and reliability of the data collected from the study and to provide guidelines for the conduct of clinical research. Information and guidance documents on GCP can be found on the FDA web site[1] and should be studied by the device team well before testing in humans.

Clinical Research Process

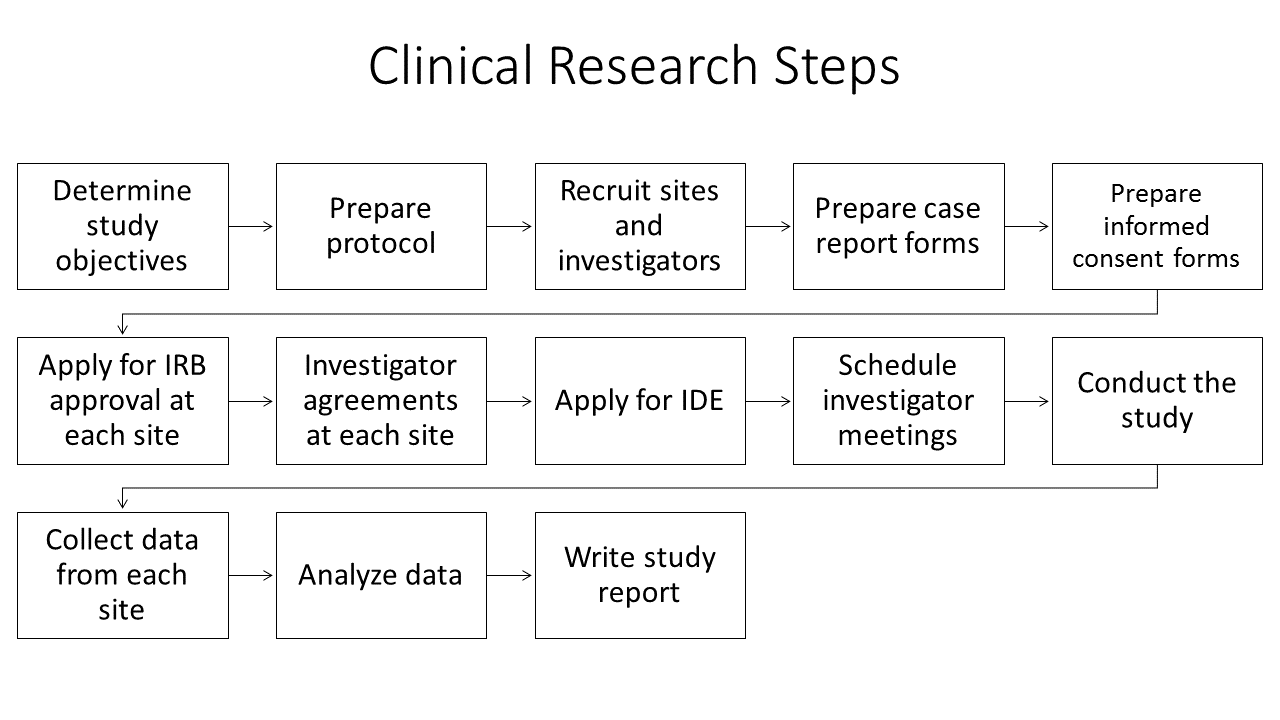

Planning for and running a clinical trial, even a small trial with a non-invasive device, requires considerable effort. Not only must the research questions be determined, there are logistical details including interacting with the IRB, coordinating multiple sites if a multi-site trial, collecting an maintaining records, including data records and assuring all principles of human subject safety and ethics are met. If this is your first time, you are strongly encouraged to collaborate with an experienced investigator.

The first step in a clinical study design is to develop the study objective which includes determining the research objective and device claims. The study objective should be phrased as a research question posed to address the proposed medical claims for the device, that is to determine if the device will work for its intended purpose. The research question should specifically address the safety and effectiveness of the given device in a well-defined patient population for one or more outcomes. If the device claims are inadequately known, before engaging in the time and expense of a full clinical trial, conduct a pilot or feasibility study on a small subgroup of patients. The purpose of such a pilot study is to identify claims more precisely, test study procedures, obtain estimates of properties of outcome or other variables and help to determine how many subjects to include in the clinical trial.

The next step is to define the study population and an appropriate clinical control that will lead to an unbiased comparison for the new device. For example, if the new device is a transcatheter heart valve then the control group might be patients receiving a heart valve through traditional open-heart surgery, or might be patients receiving a transcatheter heart valve that has already received regulatory approval. If the new device is an automated method for determining muscle block during an anesthesia protocol, then the control group is determining block by traditional train-of-four methods, possibly with side-by-side comparison in the same patient.

Study details must be determined, including the clinical, physiological or quality of life parameters to track, the proper sample size so that the study is properly statistically powered and the number of study sites, which is dictated by practical considerations of how many patients each site is likely to recruit and the availability of appropriately trained individuals who can be the local principle investigators for the study. The FDA publishes extensive guidelines on all of these considerations as well as what information from the study should be contained in a final premarket approval report.

IRB approval for the study must be obtained from each site. Important parts of the IRB review and approval process include determining the risks and benefits for research participants, how participants will be recruited and the process of obtaining informed consent from participants. Because each local IRB has different policies and procedures for reviewing and approving research involving human subjects, and because IRB approval can take weeks or months, sufficient time should be allocated for this step. Investigators are advised to review information and forms available on the local IRB web site as soon as possible.

Once the study begins, extensive monitoring functions are required including documenting all adverse events and complete case reports for each subject. The duration and frequency of follow-up information for each subject post-treatment will vary depending on the device being tested and the nature of the study.

Investigational Device Exemption

For testing new medical devices, an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) is required before beginning the study. For a significant risk device that presents serious risk to the health safety or welfare of the subject (e.g. a heart valve), IDE approval is required by the local IRB and the FDA. For a nonsignificant risk device (e.g. contact lenses), only local IRB approval is needed before beginning the study. FDA guidance documents can assist in helping you to determine if your device falls in the significant or nonsignificant risk category. The determination of whether a device is nonsignificant risk is made by the local IRB upon application by the investigator.

Some devices proposed for testing in a clinical trial may be exempt from IDE regulations. These include devices already approved for sale if used in accordance with its labeling, and some noninvasive diagnostic devices. The FDA web site has information that can help you to decide if to apply for an IDE-exempt status for your study.

After your FDA approval, your team should consider physician training as to the uses of you approved technologies or therapies, as well as making educational materials available for users and patients. Common today is the utilizatons of mixed reality educational approaches.