19 Business Models for New Products

How your product creates and captures value

Daniel Forbes

For a new product to be successfully commercialized, it must become part of a viable business model. A business model is a set of relationships that enable an organization, or some part of an organization, to sustain itself over time. This chapter will introduce the basics of a business model and explain how a business model can be developed over time. Given this Handbook’s focus on medical devices, we will focus on the case of tangible new products, as opposed to services, software, or other intangible products.

New Products and Business Models

At its core, new product development involves three different entities: an entrepreneur, a product, and a customer. New products get launched when entrepreneurs determine that a certain problem that a customer has can be solved with a certain new product. This holds whether the entrepreneur is a solo entrepreneur, an employee of a firm, or anyone else. The newness of the product and the customer problem can vary considerably. Sometimes the problem is old and only the product is new. In other cases, the problem is new and the product is only slightly new, or perhaps just a minor variation on an existing product. In either event, the entrepreneur is helping to match a product with a customer in a new way. The idea of business models comes into this picture, because most entrepreneurs are interested in serving more than one customer and they want to do so over time. As we think about serving larger numbers of customers over longer periods of time, we can no longer just think about products and customers. We will also have to think about some kind of organization—some system of organizing activity that can remain viable over time.

Organizations can take many different forms. For example, they may be set up as for-profit or non-profit corporations, or they may be a unit within a larger organization. They can also differ in size. Some organizations encompass many different people, resources, and sub-units, while other organizations are owned and run by a single person. What is common across all these organizations, however, is that they must be able to survive within a larger organizational environment. In most large, complex societies, moreover, organizational survival requires the effective management of an organization’s finances—i.e., of its money. Business models are useful here, because they provide a way for people to think about the various financial relationships involved in keeping an organization alive over time.

The most basic building blocks of a business model are revenues, which refer to money coming into an organization from its larger environment, and expenses, which refer to money the organization pays out to other entities. In general, organizations need to generate at least enough money to cover their expenses in order to survive over time. Failure to cover expenses does not necessarily lead to immediate organizational death. In fact, new organizations are often expected to lose some money when they are just starting out. Over time, however, the organization must find a way to cover its expenses or else it will be at risk of losing important relationships that it needs to survive, including relationships with employees, suppliers, investors, and eventually customers.

When we say that organizations must attend to their finances, it does not mean organizations must seek to maximize their financial gain or prioritize financial goals above all others. An organization may or may not choose to do these things, and whether it does is a function of a variety of factors, including how the organization is set up, who owns it, and how it is governed. Regardless of these factors, an organization must be financially viable, or else it will be unable to devote effort and priority to any other goals it might have.

Creating and Delivering Value to Customers

Revenues and expenses are basic building blocks of business models. But there is an even more fundamental idea underlying the business model, and that is the idea of value. In order for an organization to generate revenues, it must create and deliver value to customers by solving a problem for them. Think of the many ways we get value out of the tangible products around us. We rely on tangible products to help us make better coffee, sleep more comfortably, and do our jobs more efficiently. In each of these cases, the organizations that make these products have found ways to make our lives better (or at least they’ve convinced us they can), and they’ve also managed to get their products into our hands and to get us (or someone) to pay for them. Achieving these tasks is often a complex process involving a variety of actors. But none of them would happen without a successful value proposition—the claim that a specific problem or need will be addressed in a specific way.

It is important to note that a value proposition involves specific needs and specific solutions, and this is one reason the new product development process often begins with careful attention to customer needs. Sometimes there are different elements of need that a product can address, and sometimes the design of a product calls for tradeoffs among these elements. For example, a hand tool may be designed to be faster but only at the expense of being somewhat heavier, and it may be that the customer values both speed and lightness. In making choices about the design of the product (and later in the marketing of the product), the entrepreneur will need to be clear about exactly what value proposition is being offered to the customer. Ideally, too, it should be easy for customers to discern this proposition from the design and/or the marketing of a product so they can easily see how value will be created and delivered to them.

In summary, a good value proposition represents a compelling proposal to your target customers, and a more compelling proposal can generate more revenue by inducing more people to spend more money. On the other hand, if a product solves the wrong customer problems or fails to solve their more important problems, then its value proposition will be less compelling and will likely generate less revenue. Having said this, it is often hard for entrepreneurs to know in advance the most compelling value proposition associated with their products. It is for this reason that the development of a business model—like the development of the product itself—usually involves some back-and-forth process of prototyping and testing. The feedback from this process enables entrepreneurs to fine-tune their products and their associated business models so that they can identify and address the most important elements of value.

When we talk about the delivery of value, we are talking about how a product gets into the user’s hands—how it will actually get used in the course of a customer’s everyday life. This is sometimes an overlooked part of the value proposition, because entrepreneurs tend to presume that an effective solution will be readily adopted by customers. But the world is full of solutions that remain unadopted, because adopting a new solution can involve some combination of searching for a solution, choosing a solution, and then adjusting or adapting to that solution, and all of these processes can be costly for customers. The costs may present themselves in the form of financial expenses they impose on customers or costs in terms of the time or the cognitive or emotional demands they impose. The most successful value propositions, therefore, are those that anticipate and minimize these costs of customer adoption, perhaps by using technology (e.g., a one-click interface) or some set of existing customer relationships (e.g., building the solution into a product platform with which the customer is already familiar).

Capturing Value

The value proposition for a new product must create and deliver value to customers, and it must also capture value for the organization that offers it. This means that in addition to persuading customers to adopt a new product, organizations must somehow ensure that they receive sufficient revenues from the adopting customers. It may seem like the capture of value is an automatic consequence of value creation and delivery, but this is not the case. For example, many products will be widely adopted if they are given away or sold at a low price. Alternatively, it is possible to sell your products to customers through a wholesaler or retailer who collects significant revenue while paying you only a small fraction of what is collected. In either of these cases, you will have succeeded in creating and delivering value for customers but not in capturing value for your organization. Successful value capture requires the creation of a revenue architecture—a framework for ensuring that customers actually pay for the value you deliver through your product and that the resulting revenues actually flow to your organization[1].

Value capture is important to organizational survival for two reasons. First, it ensures the organization will have enough money to cover the expenses associated with creating and delivering value to customers. When organizations create and deliver value, they do so by integrating a variety of resources and processes. People, raw materials, machinery, real estate, and other resources must be linked together in specific and reliable ways to enable any instance of value creation. To set up and maintain these value-creating processes, the organization will need to continually procure resources from various entities in its larger external environment (e.g., materials suppliers, regulators, the labor market), and that means the organization will continually need money. Value capture ensures that the organization can cover these expenses and thereby keep its engines of value creation running.

Beyond that, value capture can enable an organization to earn profits—the extra money that is left over after expenses are paid. Profits can enhance organizational survival by providing incentives to valuable resource-providers, such as employees or investors. For example, profits can be paid out to employees in the form of bonuses. Or they can be paid out to investors in the form of dividends. Alternatively, the organization can hold onto its profits and reinvest them in its own operations, for example by periodically upgrading its equipment. Finally, profits can serve as a source of slack in the organizational system, and this in turn can make it easier for the organization to withstand jolts from its external environment, for example if a large customer fails to pay, or if there is a periodic downturn in the business. Better still, slack can provide an organization with room to play or experiment with its processes in the search for newer, better products and business models, and organizations that manage to innovate on these fronts have a better chance of surviving over long periods of time.

Tools for Developing Business Models

It should be clear from the preceding sections that the idea of value—both its creation and capture—is central to business models. Value is what enables organizations to generate revenues and to cover their expenses, and to do both of these things reliably over time. Now we can explore some concrete tools for developing business models and to consider in more detail what is involved in generating revenue and managing expenses.

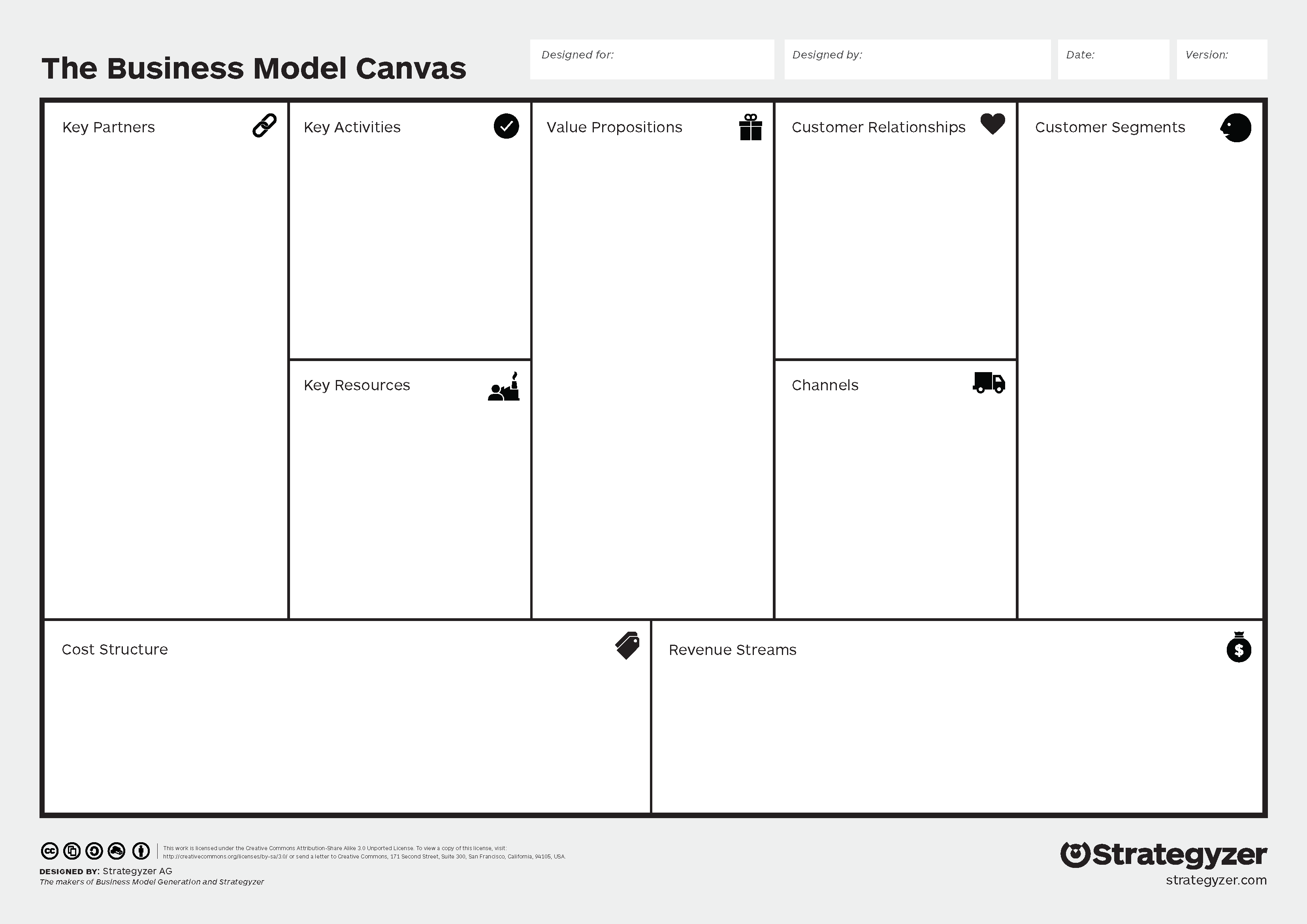

One of the most popular tools for developing business models is the Business Model Canvas. This tool was developed by a team of designers and is described in detail in the book, Business Model Generation[2]. The canvas refers to a template that presents us with a set of boxes corresponding to various components of a business model. Entrepreneurs are encouraged to consider each of these components when they seek to commercialize a new product. In particular, entrepreneurs are prompted to consider a set of questions associated with each component and to imagine alternative ways these questions might be answered.

An alternative tool for developing business models is presented by John Mullins and Randy Komisar in their book, Getting to Plan B (Harvard Business School Press, 2009). This tool, like the prior one, prompts you to think about both the revenues and expenses involved in running a new business. The Mullins and Komisar tool is a little more complicated, however, in that it is also concerned with the cash flow and investment needs of a business. These are financial considerations that go beyond revenue and expenses, and they are especially critical for independent startup firms that have no larger organizational sponsor to support their finances. For the remainder of this chapter, we’ll focus on the simpler model shown above. But knowing about this alternative model may help you recognize some of the commonalities and complexities associated with the business model concept.

In developing a business model, it is helpful to maintain an imaginative, experimental mindset. It’s almost impossible to know from the outset the best way of designing a business model associated with a new product. Rather, an entrepreneur will often be able to think of several different ways of structuring each component of the business model. Early in the process, it is useful to record all of the plausible alternatives you can think of. As time goes on, you will be able to prioritize alternatives based on how feasible and desirable they are. Over time your organization may benefit from experimenting with the components of its business model. For example, just as we can learn that customers value some elements of product design more than others, we may learn that customers are more receptive to some business model choices and less receptive to others.

The same learning process can unfold in interactions with other actors in our external environment, not just customers. For example, the expense side of the business model requires us to think about specific external partners that we work with, such as suppliers. We may discover through experimentation that certain types of suppliers, or certain types of supply arrangements, are more effective than others, perhaps because they enable us to better manage our expenses or because they equate to differences in product quality, and therefore enable us to better create and deliver value for customers. As we learn these things, we can refine the design of our business model over time, just as we may refine the design of our product.

Filling in the Business Model Canvas

To help you get to work developing a business model, the authors of Business Model Generation (BMG) propose a set of questions to help you think through each of the boxes in their model. In this section, we’ll briefly introduce these questions and consider how they might apply to a specific new device: A customized orthotic targeted to sufferers of bunions. Recently, a group of students worked on such a device for the St. Paul-based inventor Jim Hudak in the New Product Design and Business Development course at the University of Minnesota.

If you look at the Canvas, you’ll notice that the boxes shown there can be broadly divided into a right side, which is concerned with revenues, and a left side, which is concerned with expenses. Notice that the Value Proposition box is positioned squarely in the middle of the two sides. This makes sense, since the value proposition is the central concept in a business model, and it represents a link between the revenue and expense sides of the model. In order to state your value proposition, as we saw earlier, you need to state a specific solution that you’re offering to a specific customer problem. The BMG authors pose the value proposition questions this way: What, specifically, are we offering to customers? Which one of our customer’s problems are we solving?

In the case of the bunion device, the main problem being solved was bunion-related discomfort, and the main offering was a device made of synthetic materials that would be customized to the shape of an individual’s foot and would fit inconspicuously in an ordinary shoe. Although there are many bunion-related products already on the market today, many are ineffective at relieving their users’ discomfort. In this case, therefore, easing discomfort was the primary need the inventor sought to fill. But there were some secondary needs the inventor also sought to address. For example, some existing devices require the user to wear special footwear, whereas this device was designed to go with ordinary shoes.

The value proposition influences the content of the other boxes in that it helps focus what you are trying to achieve with the rest of the choices you make about your model. Your value proposition may change over time, for example in response to customer feedback or in response to opportunities that arise in connection with other model components (e.g., the chance to ally with a new partner). But you should be especially mindful about making changes to the value proposition, since it tends to shape everything else your business does.

Once you have a working value proposition in place, it is often easiest to start thinking about the revenue-focused questions found in the right-boxes. A list of the right side boxes and their associated questions appears below.

The Right Side of the Canvas: Focus on the Customer

- Customer Segments: For whom are we creating value? Who are the most important customers? Are there multiple segments?

- Value proposition: What, specifically, are we offering to customers? Which one of our customer’s problems are we solving?

- Channels: How will customers become aware of our product? How will they buy and receive it? Which channel is most cost-efficient?

- Revenue Streams: What value are our customers willing to pay? What are they currently paying for equal value? Is it a one-time or a recurring payment? Do all segments pay the same? Is the transaction a purchase, a service fee, a lease, or a subscription?

- Customer relationships: What relationships do our customers expect? How will we gain, sustain and grow such relationships? How costly are these relationships?

As you can see, even once we settle on a product (e.g., “orthotic device for feet”) and a customer (e.g., “sufferers of bunions”), we still face a range of choices having to do with how the customer will access and pay for our product. For example, it might make sense to target the bunion product to specific customer segments (Question 1), such as bunion sufferers who are female, those who are older (vs. younger), or those who are more (vs. less) athletic. In making such decisions, we will want to consider whether some of these segments suffer more than others from the problems our product is intended to solve. Or whether some of these segments are inclined to pay more (or more frequently or more readily) relative to others. This, in turn, relates to the questions of how and how much people will pay for the device. The device could be priced anywhere within a range of prices, and perhaps different devices with different features could be available at a variety of price points (Question 3).

We also need to think about how to reach our intended customers (Question 2). Nowadays, for example, foot-related devices can be sold in general retail stores (e.g., Target), drug stores, or shoe stores, as well as through online retailers, such as Amazon. More broadly, though, customers could be made aware of these devices with the help of healthcare professionals, such as podiatrists or orthotists (i.e., people who specialize in making and fitting orthotic devices).

Finally, we can think about what kind of relationship the orthotic device business should have with its customers (Question 4). For example, would each purchase be a once-and-done transaction? Or would buyers set up some sort of account with the business such that information specific to their needs (e.g., foot size and shape) could be stored and used in a series of purchases over time?

Choices on all of these fronts will factor into the business model in two key ways. First, they will give us a basis for beginning to estimate the revenues a business could actually generate over time. For example, using data on the number of customers within various segments, we can begin to estimate the number of people who would purchase the product at a given price point and how that number could increase over time. More generally, however, the choices we make about the revenue model give us a basis for thinking about the kinds of specific activities that would need to be executed in order to bring the business model to life. For example, if we intend to sell with the help of podiatrists, how will we interact with podiatrists on a large scale? Doing this would typically require the work of people with knowledge and skill related to medical device marketing in general as well as, ideally, some knowledge and connections related to the podiatry field in particular. Thus, thinking about the answers to right–side questions related to customers can help us think more concretely about the left-side boxes having to do with expenses.

The Left Side of the Canvas: What Your Firm Has and Does

- Key Resources: What are the physical, human, financial and intellectual resources needed to create value?

- Key Activities: What are the activities that must be carried out to create and deliver value?

- Cost Structure: What are the important costs in our business model? What are the expensive key resources? What costs will be incurred between now and product launch? For product sales, what are the fixed and variable costs?

- Key Partners: Whom must we work with to create and deliver value. What outside organizations can do things that we can’t? Who will be our suppliers, our manufacturers, our distribution and sales reps?

When we are thinking about tangible products, it is often easiest to start by thinking about key resources and activities (Questions 6 and 7). For example, we might need some combination of synthetic materials and some manufacturing machinery to make the bunion devices. We will also need some kind of physical space where our business-related activities can be performed. Finally, we will need people to do the work of the business. Human labor is a critical resource in most new businesses, but for some reason many entrepreneurs underestimate how much work or skill will be involved in running their businesses. Once we think about labor, too, it prompts us to think about the full range of activities involved in creating and delivering value. For example, apart from the activities directly involved in manufacturing, there are likely to be processes associated with sourcing raw materials and with selling and distributing the finished products.

Each of the resources and activities involved in our business will generally cost us something (Question 8). When we can begin to estimate those costs, we will begin to understand the cost structure of our business. For example, we will need to decide how many machines we need, and how much inventory to have on hand, and from there we can begin to calculate the costs of our operations. The space we need may be borrowed, rented, or bought. The location of our space will affect what it costs us to rent or buy it, and it may also affect the costs of certain activities, such as the cost of shipping materials to and from our space as well as the cost of the labor we employ.

It is sometimes hard to get precise information on the costs associated with a new business. For example, we may know we need a person with marketing skill, but we may not know exactly what it would cost to hire such a person. In such cases, it is often possible to estimate costs by identifying resources or activities that are analogous to those we need and then getting approximate data on their costs, either by asking people involved with the analogous businesses or through online resources.

Finally, as we think about putting together the resources, activities and costs associated with our business, we will often find that we can’t—or choose not to—do everything ourselves, and that is where partners come in (Question 9). Partnerships include any cooperative relationships our organization wants to maintain with other organizations and individuals, who may be able to do things better or more efficiently than we can. These relationships may be paid or unpaid, although partnerships that survive over the long term generally provide some benefit to both partners. Good relationships also require some investment of time to be set up and maintained.

Putting It All Together

As you can see, the business model for a new business can involve an almost dizzying array of choices. The business model canvas is designed to help you surface these choices and consider each of them carefully. In the earliest stages of a business, however, it is almost impossible to know the best way to organize. The point of the canvas exercise, therefore, is to identify some reasonable starting-point choices that will enable you to discover even better choices over time. You can discover better choices through further research, through conversations with knowledgeable advisors, or through experimentation in an operating business.

How do we know we’ve been successful? There is seldom an endpoint to the learning a business can do. Even large, long-established businesses, such as Apple or Amazon, are still learning about their business models, and the need to learn is even greater when products and customers change over time, as they often do. In the world of business models, therefore, one way to define success is in terms of survival: An organization is successful when its business model allows it to survive long enough to keep learning.

- Chesbrough & Rosenbloom (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: Evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Ind Corp Change, 11(3):529-555. ↵

- A. Osterwalder (2010) Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers and Challengers. John Wiley and Sons. ↵