5 Gathering Customer Input

Carla Pavone and William Durfee

Why Customer Input Matters

This often told quote may not have been actually spoken by Ford (the history is uncertain), but certainly represents Ford’s philosophy about product development. Here is similar, this time verified, quote from Steve Jobs:

In both cases, the inventors are right: customers cannot create disruptive solutions and cannot design the product for you. While customers are not able tell you what they want they can tell you what they need. In Henry Ford’s case, if he had asked customers about their experiences with personal transportation he would have discovered the unmet need to go faster and perhaps would have uncovered some of the customer pain points around owning and riding a horse or a horse-drawn carriage. In Steve Jobs’ case, interviews with customers would have revealed the desire by users to edit movies without the delay and expense of sending the raw footage to a service bureau.

Gathering customer input is an essential part of the product design process, and gathering that input early in the process is essential for uncovering customer needs, which in turn guides the innovator towards formulating the right problem to be solved.

Customer input, sometimes called voice of the customer (VOC), or customer discovery, or primary market research, takes place at three stages in the product development process:

- Needs Finding This happens at the front end of product development with the purpose of uncovering unmet needs in the area of interest. This involves observations of the target user in their environment and one-on-one interviews with the goal of understanding the current practice and what works and does not work about the current practice. In this stage you are not asking questions about your idea for a new product but rather trying to understand where the opportunities are for a new product.

- Concept Reactions Once you have developed one or more early-stage, unrefined concepts for products that may solve the problems you uncovered in the needs finding stage, it is time to go back to the customer to get their reactions. Input from the customer can help you to determine if you are on the right track and how to improve your idea.

- Working Prototype Reactions Once you have a refined working prototype, then go back once more to customers to gather data on what they like and don’t like about your product. The data will be more valuable if the prototype can be used by customers. For example, if your product is a new interventional catheter then this stage of data gathering might be in an animal lab with the customer trying out your product while doing a procedure.

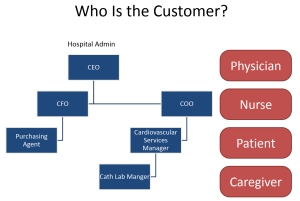

Defining the Customer

With medical technology, the first step is to determine who is the customer because only then can you begin the task of understanding the needs of the customer. While many roles may interact with the product (nurse, OR technician, surgeon, patient, caregiver) typically one role defines the target customer.

Be specific in defining the primary customer. “People” is too broad, as is “doctor”, but “interventional cardiologist” is specific. Same for “nurse” as there are many types of nurses who provide healthcare.

For some products, for example a heart valve, input can be gathered from one role: the interventional cardiologist. For other products, for example a wearable home heart monitor, input should be gathered from cardiologists (they prescribe and interpret data from the monitor), nurses (they work with the patient on product use), patients (they wear the monitor), and caregivers (they help the patient with the monitor at home.)

One-on-One Customer Interviews

One-on-one interviews are the simplest and most valuable way to get information from customers, and should be a required part of your development process. Before starting a customer interview project you should write down the answers to these seven questions:

- What is the purpose of the interviews? (What research questions do we want to answer?)

- Who are we going to interview? (Titles or roles)

- How many people will we interview?

- How will we find interviewees?

- What will we ask them?

- How will we analyze the results?

- How long do we have for this project?

Determine the Purpose

Every interviewing project needs a clearly defined purpose, the reason why you are doing the activity, which usually revolves around areas that represent the biggest unknowns. Ask yourself these questions and then use them to write down a short (three to five) list of research objectives that the interviews are designed to answer:

- What do we need to know to make a business decision?

- What do we already know?

- What do we need to find out?

- What areas are critical and what are simply nice-to-know?

Determine Who to Interview and How to Find Them

See the Defining the Customer section because you want to interview your target customer as well as others who might interact with your future product. Finding people to interview can be challenging and will test the extent of your professional network. Get to people through friends, relatives, professors, your own contacts, and LinkedIn. If interviewing patients, look for local patient advocacy groups or groups on Reddit. If you are a student working on a class or research project you have an advantage as experts are more likely to talk with students than with market research professionals.

Start early on the process of finding interviewees as many will be booking two weeks out and rescheduling causes further delays. For professionals, ask for 30 minutes but if all they have is 15 or 20 then grab it. Here is a prompt you can use in an introductory email to a contact:

Determine How Many to Interview

This is a case of the more the better. Innovators enrolled in the NSF I-Corps program are required to interview 100 users over about seven weeks. Getting that many interviews with clinicians is challenging but you should target 10 to 20 interviews as a minimum. For medical products seek out those in teaching hospitals (where the key opinion leaders tend to practice) as well as those in smaller hospitals and clinics. Aim for geographic distribution as practices at MGH in Boston may be different from Mayo Clinic in Florida which may be different from a VA hospital in Wyoming. For many product areas you will also be interviewing nurses or physical therapists, or home health care aids. Aim for 10 to 20 in each category.

One rule of thumb is to keep going until you start hearing the same thing again and again.

Create the Interview Script

Keep your script short and at a high level. Treat your script as a guide and be prepared to go where the interview takes you, which might be off-script. Your goal is to get your interviewee to tell a story about their experiences, so questions should be open-ended, for example:

- Tell me about . . .

- What happens when . . .

- Why is that important . . .

- Who else gets involved . . .

- Is ____ a problem – why or why not . . .

- How do you currently address the problem . . .

All of your questions should be about past and present, not future, behavior. Do not ask speculative “would you” questions (for example, “Would you use a product that …?”) because the answers are unreliable.

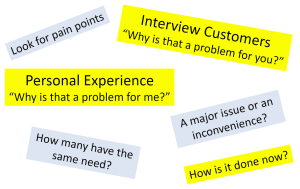

During the interview, follow up by digging deeper for the insights. Follow up questions might include:

- What do you mean by…

- Tell me more about …

- When you say ____, what exactly does that mean?

- Is ____ a major issue for you or just a minor annoyance?

Or, just keep asking, “Why?” (Google ‘five whys’ for more on this method.)

A Five-Question Interview Script

Here is an all-purpose, five question interview script from Wilcox [1] that when combined with probing (“Why is that?”) can be used for almost any needs-finding situations.

- Tell me about the last time you…

- What was the hardest thing about that?

- Why was that hard?

- What have you done to solve this problem?

- What don’t you like about your current solution?

Conducting the Interview

If at all possible, conduct your interviews in-person. Go solo or bring a note-taker but no more. A neutral location like a conference room is the best location; less desirable is the interviewees office where there will always be distractions. Start and end on time!

Start the interview with an introduction of you and the problem area you are working in. Do not talk about any solutions your team may have developed. Let your interviewee do all of the talking. If they ask you a question, bounce it right back with, “I don’t know, what do you think?”

Before doing your first actual interview, do a mock interview session with a team member or a neutral party.

Analyzing Your Interview Data

Immediately after each interview, review your notes or audio recording transcripts and pull out the key insights you learned from the session. When you have 10 to 20 interviews then look for commonality among the key insights.

Create a report that has these sections:

- Research Objectives (what you were trying to find out)

- Participants (who you interviewed: roles and numbers, not names)

- Key Findings (your insights)

Report key findings qualitatively, for example, “Most interventional cardiologists thought that…” Use words like ‘most’, ‘several’, and ‘few’ rather than reporting percentages (“22.5% thought that”) because the numbers are too small to apply statistics. You are looking for patterns rather than statistics-based hypothesis testing. Highlight any differences of opinion that you heard. Avoid highlighting singular comments that you heard from only one respondent.

Include your interview script in the appendix.

When the Purpose is Reactions to Concepts

If testing a concept, state, without selling, who the concept is for and what the concept does. Avoid bias in your description. Get their overall reaction, their likes and their dislikes. Do not ask about the price point because for medical products the user (doctor or nurse) is not the purchaser. Have a thick skin because respondents may not like your pet idea, which is hard. This why it can be better for someone other than the inventor to conduct concept reaction interviews.

Creating Need Statements

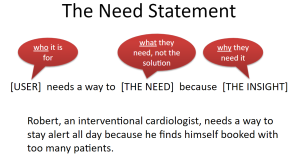

After you have gathered customer input through interviews and observations, a useful way to form conclusions about what you found out is by creating a list of unmet customer needs. From there, screen and combine to end up with one or two needs that (1) are related to a specific and significant problem, (2) are feasible to be met through an inventive process, (3) if met will lead to a significant improvement in a health care procedure or outcome, and (4) are connected to a significant market opportunity.

From your narrowed list of needs, convert into one or two structured needs statements as suggested by the template in the figure above. Be specific in defining the user and make sure that the statement expresses a need not a solution. For example, “needs a hammer” expresses a solution while “needs a way to join wood” expresses a need. Well-crafted need statements can be used in all the following phases of the innovation process and are particularly useful when screening ideas. Remember that a final need statement must be backed up by the evidence gathered from your customer and disease state research.

References

www.talkingtohumans.com

(Free for students and academics)

- Wilcox, How to Interview your Customers, customerdevlabs.com/2013/11/05/how-i-interview-customers/ ↵