13 Biosecurity

Learning Objectives

- Define bioexclusion and biocontainment

- Define what is meant by a reportable disease and identify whether a given disease is reportable in the state of Minnesota

- Define open versus closed herds

- List and explain a variety of risks of disease introduction and movement through a facility

- Describe appropriate use of disinfectants

- Create a list of best practices regarding control of biosecurity by management of visitors to a facility

- Describe common practices in food animal and companion animal facilities to mitigate risk of disease introduction and movement

*

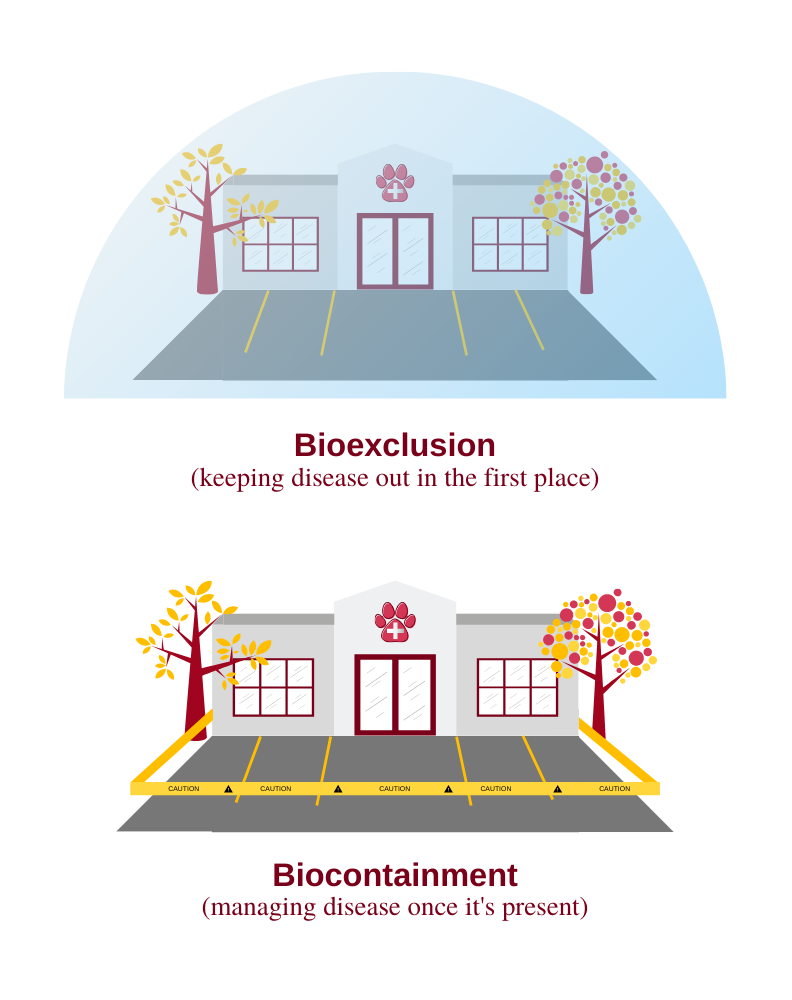

Bioexclusion and Biocontainment

Biosecurity is split out by some into bioexclusion, also called external biosecurity (preventing disease from entering a facility) and biocontainment, also called internal biosecurity (managing a disease once it is on the premises). Biosecurity in general is a concern for populations of animals and the facilities where they are housed. If the disease of concern is a zoonotic disease, precautions to protect those who work in those facilities or otherwise interact with those animals also are in order.

The concepts of biosecurity are presented here to help you see the continuum of infection control in veterinary medicine. We often concentrate on infection control in the hospital (wearing gloves or other personal protective equipment, using foot baths in the large animal hospital to prevent spread of disease by traffic through the facility, properly using isolation facilities). For many veterinarians, that is the full scope of their responsibility in addressing biosecurity. For others, including everyone who works with groups of animals, whether that be a herd of cattle or a group of cats in a rescue facility, knowledge of principles of biosecurity can prevent disease from being introduced or spreading in a facility and is a cornerstone of preventive care for those animals.

Concepts of biosecurity are of concern for any disease-causing organism. Some organisms and diseases rise to a higher level of concern and oversight. These reportable diseases are those that we are required by law to report to the state Board of Animal Health so appropriate biosecurity measures may be enforced to prevent widespread disease with subsequent economic consequences and the potential for loss of human and animal life. The list of reportable diseases in Minnesota, the timing of reporting, and the type of testing to be performed are updated constantly.

*

Food Animal Facilities

Food Animal Facilities

Much of the information in this section is from the following website: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock/vet/facts/04-003.htm

Biosecurity at the farm level can be defined as the management practices enabling producers to prevent the movement of disease-causing agents onto and off of agricultural operations. This includes environmental contamination. Biosecurity therefore involves many aspects of farm management, such as disease control and prevention (e.g. closed herd, vaccinations), nutrient management, and visitor control. Closed herds are those defined as having no new animal introduction into the established herd; either all animals move as a cohort, leaving the facilities empty for a while (all in-all out), and/or all replacement animals are born on the farm (a process called internal multiplication). Keeping the herd closed is extremely difficult for a producer, so most choose to introduce new animals into the herd after they undergo testing and quarantine before introduction. Although controlling and limiting the movement of livestock is recognized as the most important biosecurity measure for most diseases, many important hazards can be carried on contaminated clothing, boots, equipment, and vehicles.

A question for you to ponder – If you have a herd of grazing cattle that you manage as a closed herd, can you have free-roaming chickens as long as they don’t leave the property?

Biosecurity has become a major concern to the agriculture industry as a result of foreign and emerging disease issues, the globalization of agriculture, and increasing public concerns over food safety. Individual farms are less isolated and inputs are entering the farms of today from further away, often from other countries. Issues such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy, foot and mouth disease, avian influenza, and Newcastle disease have brought world concerns closer to the local farm level.

Practices do not have to be cumbersome, confusing or expensive, but a small investment in time and money can yield big benefits for the farmer, the industry, and for the consumer through improved food quality and safety.

Disease Spread Risks

What are the chances of introducing disease? The single biggest risk factor in disease is purely mathematical in that the higher number of animals in any facility or on any one site, the greater the chances of disease spread. Other risk factors include:

- Direct contact between animals on the farm and newly purchased animals

- Mechanical spread by animal transporters

- Mechanical spread on contaminated farm equipment, boots, clothing, and contractors cables and tools

- Movement of birds, mice, rats, flies, dogs, cats, and wildlife

- Airborne spread in aerosols or dust / dirt, affected by the herd location, wind, animal density, and neighbors

- Contamination of feed, water, and bedding

- Contamination of the environment on farm – moving animals from diseased pen or hospital leads to dirty passages and yards

- Biting insects

Mechanical Transmission

Infection present in feces, saliva, nasal secretions, blood, milk, or semen may be mechanically transmitted between animals on a variety of inanimate objects (fomites). The body fluid is not the fomite. If you sneeze on your cell phone, the cell phone is the fomite. The time that these fomites remain infectious depends on the resistance of the organism, the temperature, amount of sunlight, dryness, and level of disinfection.

Guidelines for Buying Breeding Stock and Minimizing Risks

If you have any doubts about the health of breeding stock, don’t buy those animals! Health is worth far more than genetics. Producers should work with veterinarians to make sure the veterinarian completes all necessary health assessments and testing. The buyer should only work with sellers who are completely open about the health status of the animals. Isolate incoming animals for at least 3-4 weeks and if possible limit the number of intakes of live animals. Guidelines for buying breeding stock include:

- Know the disease status of both the recipient and source herds.

- Consider the location of both herds and the surrounding disease risks.

- Recognize the limitations of recipient herd biosecurity.

- Select an appropriate single source for replacements.

- Check and test disease status including history and past and present customers.

Guidelines for Isolation Units

No matter how reliable the health status of the herd of origin is, it is important that incoming animals undergo a period of isolation for at least 3-4 weeks. The biosecurity of the quarantine unit ideally should be better than that of the home unit, and the isolation unit should preferably be on another site, managed by different staff or at least with dedicated boots, clothing, and equipment used. There should be no slurry or drainage crossovers and an all in-all out policy should be in place with thorough cleaning and disinfection between batches. Regular clinical and veterinary inspections / tests should be carried out with all diseases and deaths being investigated.

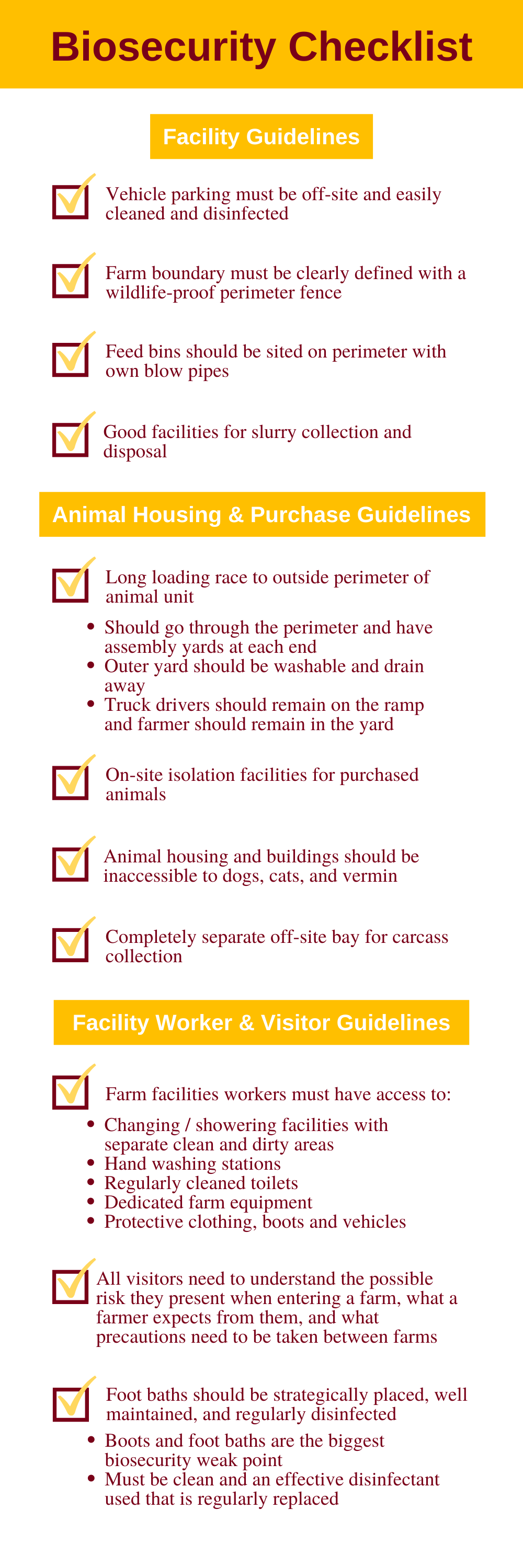

Checklist of Physical Biosecurity Measures

- Strategically placed, well maintained disinfectant footbaths

- Off-site vehicle parking, easily cleaned and disinfected

- Defined farm boundary and wildlife-proof perimeter fence

- Changing / showering facilities with separate clean and dirty areas

- Hand washing and regularly cleaned toilets

- Dedicated farm equipment, for example, protective clothing, boots and vehicles

- Long loading ramp to outside perimeter of animal unit

- Completely separate off-site bay for carcass collection

- On-site isolation facilities for purchased animals

- Feed bins sited on perimeter with own blow pipes

- Bird and vermin proof buildings

- Good facilities for slurry collection and disposal

Livestock Loading and Unloading

Animal loading areas are always a weakness. The ramp is often not long enough, or far enough away from the buildings. It should go through the perimeter and have an assembly yard at each end with the outer yard washable and draining away from the unit. Truck drivers should not come into the unit, they should remain on the ramp and likewise, the farmer should not go onto the truck.

Disinfection and Disinfectants

Disinfection is targeted at reducing disease spread from contaminated boots, buildings, yards, equipment and vehicles. Disinfection will not work without proper cleaning and removal of all organic matter. It is vital to dry and rest buildings before final disinfection and equally vital that all surfaces are saturated. The drying and resting of buildings for 3-4 days before final disinfection improves efficacy to over 99%. The sequence for cleaning a building looks like this – (1) soak all surfaces with water – (2) powerwash to remove the bulk of the organic matter – (3) use detergent to break down what’s left – (4) powerwash again – (5) let the building dry – (6) apply disinfectant.

In any operation, boots and foot baths are the biggest weaknesses! Clean boots are vital and every farm should have them for staff and visitors alike. Remind everyone to be biosecurity conscious and to reduce transmission between buildings, hospital pens, and birthing pens. Foot baths must be clean and an effective disinfectant used that is regularly replaced. Remember that the boots must also be cleaned of organic matter; use of footbaths alone will not disinfect boots adequately. The ideal disinfectant has the following characteristics:

- Proven broad spectrum activity and efficacy

- Fast acting to rapidly kill very infectious agents

- Active in the presence of organic matter

- Stable after dilution, especially in footbaths

- Safe for environment, animals and people

- Non-corrosive and suitable for a range of surfaces, for example, porous and other applications

- Easy to store, move and dispose of

- Cost effective – do not judge by smell

Truck Wash and Disinfection

As mentioned earlier, trucks can and do bring infection onto a farm. They are often washed at the factory or rendering plant and contaminated equipment, hoses, and boots are put onto the truck. Wheels and wheel arches are a big risk. Ideally an off-site washing stand is required at the truck driver’s home base.

Vermin Control

Animal housing should be inaccessible to dogs, cats, and vermin. Control of birds and insects is vital to prevent spread of disease.

Biosecurity for Workers and Visitors

Staff training and their vigilant attitude is the best defense. How often do they have explained to them the importance of changing clothes and boots and doing the biosecurity disciplines? Do you have standard operating procedures (SOPs), which are agreed ways of doing each task? Simply written, these should improve staff members’ understanding of why certain procedures are in place.

All visitors need to understand the possible risk they present when entering a farm, what a farmer expects from them, and what precautions need to be taken between farms that are visited. This applies to anyone entering or leaving the premises who may be visiting other livestock operations, and not just those of the same species or commodity type. The list includes:

- neighbors and friends;

- agribusiness and service representatives;

- veterinarians;

- municipal/regulatory personnel, inspectors;

- dead stock collectors / renderers;

- custom manure/biosolids haulers and applicators.

Visitors can unknowingly bring harmful agents onto a farm via contaminated clothing and footwear, equipment, or vehicles. Equipment used to repair buildings and machinery, to treat or handle animals, and to carry out testing or procedures are all potential sources of contamination. The risk is increased with visitors who regularly go from farm to farm as part of their employment or routine. Such individuals, businesses, and organizations are encouraged to develop and follow a biosecurity plan. All visitors, farm owners, and their employees have a shared responsibility in biosecurity. Visitors need to be aware of that farm’s level of biosecurity and need to follow their recommendations. Visitors must be prepared to accept all reasonable directives from the farmer when visiting his or her operation. In many swine operations, for example, showering in and out of facilities is a requirement.

Farmers and their employees also have a responsibility to prevent hazards from leaving the premises. Wear clean clothing and footwear when leaving the farm, particularly if visiting other farms, feed supply agencies, veterinary facilities, or auction markets.

All visitors should make an appointment so that both parties can make best use of their time. The visitor should ask the farm operator about his or her biosecurity protocol and any special measures that must be taken.

Assessing Visitor Risk and Controlling Access

Risk assessment is a method of determining the likelihood and severity of the risk posed by a visitor. By identifying key risk factors, appropriate procedures and protocols can be determined.

Guidelines for Visitor Risk Assessment

| LOW RISK | MODERATE RISK | HIGH RISK | |

| Number of farm visits per day | No other farm contact | One or occasionally more than one farm per day | Routinely visits many farms or auctions |

| Protective Clothing | Wears sanitized shoes or boots. One pair of clean coveralls per site | Wears sanitized shoes or boots – If clean, may not change coveralls | Does not wear clean or protective clothing |

| Animal Ownership | Does not own and/or care for livestock | Owns and/or cares for a different species | Owns and/or cares for a similar species and production type |

| Contact with animals | No animal contact | Minimal or no direct contact – exposure to housing facilities | Regular direct contact with animals |

| Biosecurity knowledge | Understands and promotes biosecurity for industry | Aware of basic biosecurity principles but is not an advocate | Little appreciation or understanding of biosecurity principles |

| Foreign travel | Does not travel out of the country | Limited travel outside of the country without animal contact | Travel to foreign countries with animal contact in those countries |

Biosecurity Guidelines for Visitor Control

- Provide a farm gate sign indicating biosecurity levels in effect on the farm. Place restricted entry notices on the doors to animal facilities.

- Keep service vehicles as far away from the animal facilities as is feasible. Designate a parking area for vehicles entering the farm, away from traffic areas used by farm vehicles and away from feed and manure. Visitors’ vehicles should be visibly clean of manure and organic matter.

- Establish one area of the farm for visitors to enter if required. All visitors should go directly to the entry point. Consider installing a bell or alarm system for visitors to indicate their arrival.

- Keep a visitor log or record of the names, dates, and vehicles that visit.

- Determine if, when and what types of farms have been visited prior to your farm. As a precaution, 48 hours may be required between visits (1 week for foreign visitors).

- Restrict access to animal facilities to essential visitors only. Keep visitors out of animal pens and feed alleys, and do not allow direct contact with animals if not essential.

- Insist on clean clothing and/or supply clean boots and clothing at your farm.

- Do not allow foods of animal origin to be brought onto the premises.

- Provide a container or plastic bag for collecting dirty clothing or disposable items used by visitors.

- Ask visitors to wash their hands prior to leaving the premises, especially if in contact with animals. If hosting tours, provide hand washing facilities or disinfectant hand gel. If food is to be served, do this away from the animal facilities and after hand washing.

- Provide a footbath and a container of an appropriate disinfectant solution with a scrub brush at the entrance to each facility. Maintain these with daily cleaning, remove accumulated organic matter, and replenish disinfectant regularly. Footbaths alone are not an effective means of disinfecting footwear.

- Ensure all equipment used by visitors has been thoroughly cleaned and disinfected and stored appropriately before being used on your premises. Also clean and disinfect all borrowed equipment and tools prior to use on your farm and before returning them.

Proper use of disinfectants is a critical component of biosecurity. Use all disinfectants according to product recommendations.

Some facilities use ultraviolet (UV) germicidal chambers to decrease number of pathogens on objects that could introduce disease into farms. Recent work by Dr. Torremorrel and Summer Scholar Katelyn Rieland from the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine has verified that use of these products reduces risk of introducing pathogens but does not guarantee it. Guidelines that should be followed when using products such as these include frequently cleaning the chambers and replacing the UV bulbs, and rotating objects for optimal exposure to UV light.

Manure and its Concerns

Many important diseases can be transmitted by manure, either directly or indirectly, via contaminated clothing and equipment. The pathogens responsible can be classified into four major types:

- bacterial (e.g., Salmonella, E. coli, Johne’s disease, tuberculosis);

- viral (e.g., hog cholera, foot and mouth disease, bovine viral diarrhea);

- protozoal (e.g., coccidiosis, cryptosporidiosis);

- parasitic (e.g., ascariasis, sarcocystosis).

Fungal diseases, such as aspergillosis, are less likely to be shed in manure, but may be present in contaminated bedding and litter.

As production costs increase, more producers are contracting professional manure handlers and haulers. However, there is a risk of disease being introduced by hiring custom labor. Improper sanitation procedures between farms can potentially spread a number of diseases. Ensure manure management equipment is properly maintained and cleaned, especially if being used at several farm sites. Wash all exterior surfaces of manure handling equipment; check that they are visibly free of organic matter before arriving on a farm.

Summary for Food Animal Facilities

Biosecurity is an essential component of many on-farm food safety programs and provides:

- greater consumer acceptability of the quality and safety of the food supply;

- healthy animals that are more productive;

- improved animal welfare and well-being;

- improved efficiency and profitability for the farmer.

Whether it is the relatively controlled environment of a poultry production facility, or the more open pasture of a beef or dairy operation, biosecurity is critical. Over the past decade, food safety, public health and animal health have gained greater importance throughout the world. Quality assurance and HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points) programs originate at the primary production level – the farm – with biosecurity planning a key role for the entire food production chain.

Because hazards and risks vary among species and types of operations, what works for one farm may not be appropriate or effective for another. Each farm needs to develop a specific, documented biosecurity plan in consultation with their veterinarian. Visitor control as presented in this information is just one component of the complete biosecurity plan.

The fundamentals of developing a biosecurity plan are:

- Identify possible risk factors.

- Identify critical control points for your operation.

- Set limits or standards for your farm.

- Set up a monitoring schedule and procedures.

- Keep effective records.

*

Companion Animal Facilities

Horses

Horses

General principles of biosecurity apply although facilities that house horses often are less stringent than facilities that house food animals unless a disease outbreak has occurred. This is a good thing for us to watch for when we visit equine facilities as we can help them improve biosecurity and prevent disease outbreaks. Attention should be paid to likelihood of new animals introducing disease into an established group of horses. Some vaccinations also are more likely to be recommended for horses that have greater exposure to groups of horses, for example at shows or sales barns. In any horse facility that has animals that are not healthy, it is wise to always care for the healthy animals first, including young animals, and then care for those that are ill, so there is less risk of the person who provides daily care transmitting disease through fomites. Foot baths are a good measure to try to minimize disease movement within and between buildings.

Most medical facilities for horses will have a dedicated area for isolation of horses with potentially contagious disease. This is not true at all locations that board or otherwise house horses and it is valuable to help owners recognize when there is a serious risk to biosecurity. General guidelines for immediate admission of horses to an isolation unit as they enter a medical facility include:

- Any 2 of the following 3 signs – diarrhea, fever, neutropenia (low white blood cell number)

- A primary complaint of diarrhea that is not obviously physiologic

- A positive diagnosis of a known contagious / zoonotic disease

- Fever greater than 102°F accompanied by any 2 of the following signs – cough, nasal discharge, lymphopenia (low number of lymphocytes)

- Clinical signs suspicious of equine herpesvirus 1 (neurologic signs)

Clients should be made well aware of the list above, so they know to contact their veterinarian immediately if any of these signs occur, both for the sake of the affected animals and for other animals in the facility.

Dogs and Cats

Dogs and Cats

As with equine facilities, often facilities that house large numbers of dogs and cats do not have stringent biosecurity protocols unless a disease outbreak occurs. Boarding kennels usually require some sort of verification of health of animals before they are allowed to enter but these often are superficial and not based in science. For example, most boarding facilities require that dogs and cats be vaccinated for specific diseases before entry, but will permit those vaccinations to have been given the day before, such that animals are brought to the facility well before any immune response could have been generated.

Most biosecurity protocols that are published for animals are for humane societies and small animal clinics, where there is great likelihood of mixing of healthy and diseased animal populations. Policies to minimize introduction and spread of disease in these facilities, as generated by the American Animal Hospital Association, include:

- Having separate entrances for animals with possible infectious disease and having signs to direct people to those entrances appropriately

- Requiring staff to wear appropriate personal protective equipment

- Posting and following very specific cleaning and disinfecting measures

- Using specific examination rooms or housing areas for animals with infectious disease, perhaps even disease-specific (a set of runs only used for dogs with suspected parvovirus, for example)

- Having dedicated staff for infectious disease patients who do not interact with healthy animals in the facility

- Training all staff and faculty in biosecurity protocols

- Developing a surveillance program to ensure that breaks in protocols are identified and that disease outbreaks are caught early

*

Extra Resources

Extra Resources

- List of reportable animal diseases in Minnesota: https://www.bah.state.mn.us/reportable-diseases/

- Animal facility information: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/livestock/vet/facts/04-003.htm