14 Backyard Poultry / Caged Birds / Fish / Reptiles / Amphibians

Learning Objectives

- Describe unique internal and external anatomy of birds, amphibians, and reptiles

- Describe diseases against we vaccinate chickens

- Describe principles of disease control in chickens

- Describe common parasites of chickens and their control

- Describe housing considerations for chickens, caged birds, reptiles, and amphibians

- Briefly describe normal behaviors of birds, reptiles, and amphibians

- Briefly describe nutritional requirements of birds, reptiles, and amphibians

Information in this and the next two sections (Mammals I and Mammals II / Marsupials) is not inclusive of all disease conditions or common concerns in these species and instead will focus on relevant aspects of housing, vaccination / diseases, parasite control, behavior, dentistry, biosecurity, and nutrition. The information about poultry is about backyard chicken flocks and not all of this information is appropriate for large-scale poultry production operations.

*

Backyard Poultry

Backyard Poultry

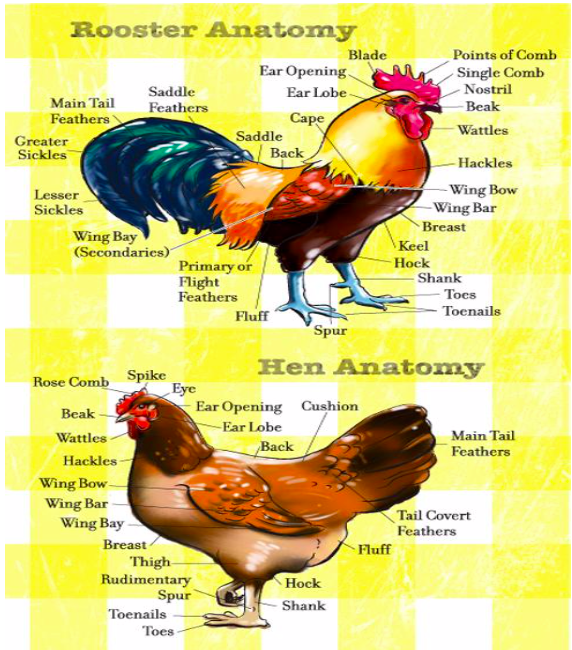

Unique Anatomy – External

Unique Anatomy – Internal

The avian skeleton differs from that of mammals by the presence of a large keel, which supports muscle to permit flight, and by modifications of the forelimbs as wings. Some of the bones contain air spaces, which make the skeleton lighter and again, permit flight. A nice review of the avian skeleton can be found at this link.

The respiratory tract of birds is dissimilar to that of mammals in that they have no diaphragm. Air is pulled in and forced out by movement of the rib cage and keel. Chickens have a trachea that bifurcates into bronchi. The syrinx (voice box) is located at the bifurcation of the trachea into bronchi. From the bronchi, air moves into the lungs, where gas exchange occurs. From the lungs, air moves into large air sacs.

The gastrointestinal tract begins at the beak. The tongue has barbs that help direct food into the esophagus. Birds do not swallow; movement of the tongue forces food into the upper esophagus. The crop lies midway along the esophagus. It is a place where food can be stored and moistened; no digestion takes place in the crop. The crop serves the same purpose in prey birds as rumination does in cattle, in that it permits the bird to ingest a large amount quickly and then to digest it later, in a safer location. From the lower esophagus, food moves through the proventriculus (glandular stomach) into the ventriculus or gizzard (muscular stomach) where it is physically broken down. Food then moves into the small intestine where enzymatic digestion takes place and nutrients are absorbed. Paired ceca lie at the junction of the small and large intestines. Not all ingesta pass into the ceca, which primarily function to break down dietary fiber. The short large intestine is attached to the cloaca, which is a common chamber for the gastrointestinal, excretory, and reproductive tracts.

The excretory tract consists of paired, trilobed kidneys that lie posterior to the lungs and bilateral ureters that empty directly into the cloaca. There is no urinary bladder. Metabolic wastes (urates) are deposited onto the feces before being expelled.

The reproductive tract in chickens is unilateral. The left ovary and oviduct are functional and the right ovary and oviduct regress. The left oviduct is made up of the infundibulum, which catches the yolk as it released from the ovary; the magnum, which secretes albumen; the isthmus, which secretes the inner shell membranes; the shell gland, which secretes the calcium carbonate shell; and the vagina, which secretes the outer cuticle of the shell and any pigments, and directs the egg for laying (oviposition). Birds begin laying eggs at about 6 months of age and lay until about 3 years of age. It takes 23-26 hours for an egg to form and be layed. Chickens will lay a clutch of 3-8 eggs and then take a day or so off before beginning laying of another clutch. A flock of laying hens can be maintained without a rooster; chickens will lay unfertilized eggs if no rooster is present.

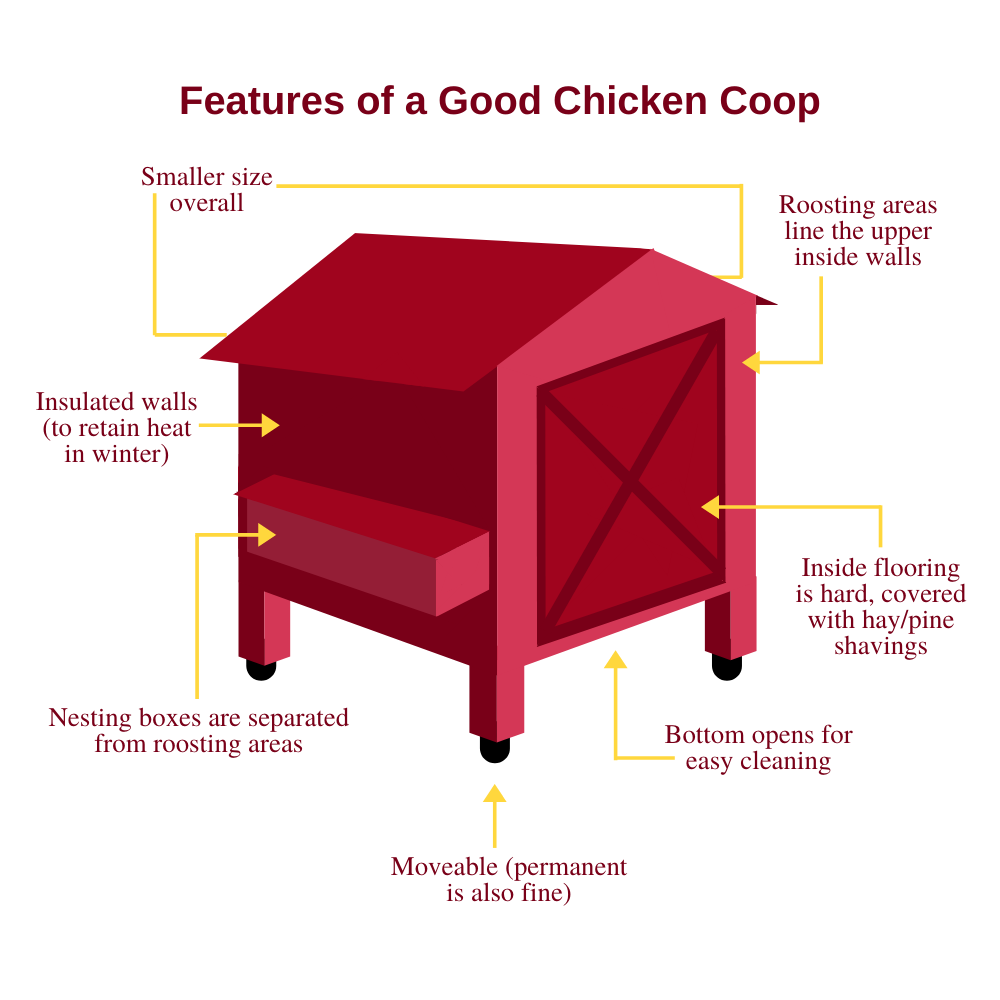

Housing

Local ordinances determine whether or not people can keep chickens, especially in urban areas, and may place restrictions on sex of birds (no roosters, for example) or total number of birds. It is the client’s responsibility to investigate and follow these ordinances.

Most backyard chicken flocks are small. Single chickens are lonely and if you have only two chickens, they are likely to fight. For that reason, a minimum of three chickens works well for most people.

You do not want the coop to be too palatial; a smaller, insulated space will retain heat better in the winter. You should provide about 2-5 square feet per bird in the coop and 8-10 square feet per bird for outside enclosures. Chickens should be provided with indoor housing where they can nest and roost. The chicken coop should contain nesting boxes that are separate from roosting areas and are not directly below roosting areas, so they do not become soiled with droppings. You should have at least one nest box for every 3-4 birds. Birds will roost at the highest point available to them. Coops can be permanent, on a concrete or wood base, or can be movable and placed on grass or pasture. Hard flooring should be covered with clean, dry straw or pine shavings. Protection from predators includes protection from owls and hawks; a covered, fenced area is recommended for birds given access to the outside. The coop should be well ventilated to permit enough air flow to decrease moisture and thereby minimize odor of ammonia from droppings. Keeping bedding clean and dry also will help control insects. Keeping feed securely stored, ideally in closed containers, will help control rodents.

Chickens are sensitive to daylength. Chickens require about 12-14 hours of light daily to continue laying; with decreasing daylength, they layer fewer eggs and eventually molt, which will stop egg laying temporarily. Nest boxes should be checked for eggs 1-2 times daily.

Droppings must be regularly cleaned out of the coop. Disposal or management of waste is dependent on local ordinances. Uncomposted chicken droppings cannot be used directly as fertilizer as the high nitrogen content will burn plants.

Fresh water must be available at all times and in winter, care must be taken that water does not freeze.

Clients who keep chickens in cold environments may wish to insulate the coop; a student from the class of 2019 informed me that chickens in Minnesota can freeze off their combs if it gets too cold in the coop. Combs and wattles are needed by the birds to help regulate their body temperature. A student from the class of 2022 tells me that freezing can be minimized by applying petroleum jelly to the wattles and comb but be aware that freezing is still possible if the temperature is well below freezing and the coop is not insulated. Some owners provide heat lamps. Use of electricity in a coop may be controlled by local municipalities.

Vaccinations and Disease Control

Many diseases in chickens can be controlled by vaccination of breeding hens to produce disease-free chicks or by vaccination of chicks themselves. It is always best to get chicks from a breeder or hatchery that is part of the National Poultry Improvement Plan. Any drug therapy must be evaluated for its use in laying hens as it may affect use of eggs layed by treated hens or ability of the owner to use those hens for meat. Indiscriminate use of antibiotics will not consistently prevent or control disease in flocks.

Overall, to prevent disease in backyard poultry, the following steps should be taken:

- Purchase birds from breeders or hatcheries that follow the National Poultry Improvement Plan.

- Have dedicated shoes and clothing for working with the birds. Thoroughly clean the coop to remove organic materials before disinfecting; cleaning and disinfection of the coop and tools (feeding scoops, rakes, etc.) should be performed daily.

- Restrict human traffic in and out of the area where the birds roam.

- Protect the chickens from exposure to wild birds including waterfowl.

- Monitor the flock daily for signs of illness.

- Properly dispose of dead birds (follow local ordinances).

Diseases of concern include:

- Infectious bronchitis

- Newcastle disease

- Laryngotracheitis

- Fowl pox

- Infectious coryza

- Mycoplasma

- Fowl cholera

- Marek’s disease

- Avian influenza

Infectious Bronchitis

This is probably the most common respiratory disease of chickens. It is caused by a coronavirus with variable antigenicity; new serotypes arise regularly. Signs and severity of disease vary with the specific coronavirus, age of the bird, and presence of any secondary infections. The virus is highly contagious and spreads readily between birds by direct contact, aerosol spread, or via fomites (inanimate objects). Spread of the disease through a flock is worsened by poor ventilation and overstocking of birds. Clinical signs include depression, loss of appetite, coughing, gasping, and diarrhea. This disease is best controlled by vaccination.

Newcastle Disease

This is a highly contagious disease caused by paramyxovirus-1. This is a high morbidity disease with depression, loss of appetite, respiratory signs, twisted neck (stargazing), and leg paralysis. The disease is transmitted between and within species of birds, via aerosols, and by fomites including visitors to the facility. This disease is best controlled by vaccination.

Laryngotracheitis

Infectious laryngotracheitis is caused by a herpesvirus with variable pathogenicity. Spread between birds is slow but the disease can be spread between farms by fomites or aerosol spread. Signs include gasping, coughing up of mucous and blood, and ocular and nasal discharge. The hallmark clinical sign for this disease is “pump handle respiration”, which is where the bird is trying to breathe in such a way that its head goes up and down, looking like an old well pump handle. Control is through vaccination if the disease is enzootic (regularly present in a population) or epizootic (a sudden widespread outbreak) in an area. Sick birds that recover and vaccinated birds should be housed separately from susceptible birds. Infectious laryngotracheitis is a reportable disease in Minnesota.

Fowl Pox

Fowl pox is a pox virus that manifests as skin lesions and pharyngeal plaques. Fowl pox can have both dry and wet forms. Respiratory signs are evident only with the wet form. The wet form of this disease can present very similarly to infectious laryngotracheitis. Spread through a flock is slow. Transmission is through skin abrasions or by the aerosol route; birds, mosquitoes, and fomites may transmit the virus. The disease is more common in male chickens because of their greater tendency to fight and suffer skin wounds, and in areas where there are biting insects. Birds will be sick for about 2 weeks and there is no effective treatment. This disease is best controlled by vaccination.

Infectious Coryza

This is a chronic, highly infectious disease of chickens caused by Avibacterium (formerly Haemophilus) paragallinarum. This disorder is more common in the southern United States and in California than in the upper Midwest. There is rapid transmission through direct contact between birds in a given flock. Signs include swelling of the face and wattles, purulent ocular and nasal discharge, sneezing, and dyspnea. Various antibiotics may be used for treatment but the disease is best controlled by stocking birds only from known disease-free breeders or hatcheries. Vaccinations may be used in areas of high incidence.

Mycoplasma

Chronic respiratory disease due to Mycoplasma gallisepticum or Mycoplasma synoviae may be seen in chickens. The organism can be spread through aerosols, airborne dust or feathers, or by direct contact. Recovered birds remain infected for life and may express disease when stressed. Birds show respiratory signs as described above and also may show arthritis. Treatment with some antibiotics is possible; secondary disease conditions must be addressed and the environment cleaned. The disease is best controlled by stocking birds only from known disease-free breeders or hatcheries.

Fowl Cholera

Pasteurella multocida is the bacterial cause of this highly contagious, high mortality disease in chickens. Transmission is through direct contact with nasal exudate or feces of infected birds, or via fomites including contaminated soil, equipment, and workers. Clinical signs include loss of appetite, ruffled feathers, coughing, ocular and nasal discharge, swollen face and wattles, arthritis, and diarrhea. Risk of disease is worsened if concurrent infections are present or if birds are overstocked. Treatment with antibiotics is possible but disease may redevelop after medication is stopped. The disease is best controlled by vaccination.

Marek’s Disease

Marek’s disease is caused by a herpesvirus that has several manifestations. Neurological disease may be evidenced as paralysis of the legs and wings. The visceral form is evidenced as growth of tumors in the cardiac and skeletal muscle, lungs, and reproductive tissues. The cutaneous form is evidenced as tumors in the feather follicles. Peripheral nerve enlargement and “Marek’s eye” also may be seen. Mortality in affected chickens is 100%. The route of infection is through the respiratory tract and transmission may occur through exposure to affected feather dander or via fomites. There is no treatment. The disease is best controlled through vaccination of chicks. A combination of vaccines commonly is used to ensure broad immunity is induced. Genetic resistance exists and breeders may select for stock with increased frequency of the gene that confers this protection. Again, chicks should be purchased through breeders or hatcheries that provide vaccinated birds.

Avian influenza

Avian influenza is caused by an influenza type A virus and can infect domestic and wild poultry and waterfowl. Low pathogenicity avian influenza is commonly carried by migratory waterfowl. It can infect domestic poultry but rarely causes illness. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is extremely infectious, spreading rapidly between flocks, and causes serious illness or death. Clinical signs of chickens infected with HPAI include depression; difficulty breathing; swelling or purple discoloration of the head, comb, and wattle; decreased egg production; and sudden death. Avian influenza is a reportable disease in Minnesota. Owners of backyard flocks are recommended to protect their flock from HPAI by avoiding attracting wild birds, especially waterfowl by enclosing feed and reducing standing water, limiting movement of chickens to and from the property (for example, to attend shows or sales), and limiting visitors to the property that interact with the birds. Good information is available from the University of Minnesota Extension Service and the USDA.

External Parasite Control

External parasites found in birds include:

- Biting lice

- Feather and leg mites

- Red mites and northern fowl mites

Biting Lice

Lice are spread by direct contact between birds and from infested litter. Life cycle of the parasites is about 3 weeks. Rapidly moving insects will be visible at the base of the feathers on the abdomen or around the vent. Clumps of eggs (nits) may also be visible at the base of the feathers. Various powders and sprays are approved for application on birds including malathion and pyrethroids. Treatment may need to be repeated as not all life stages of the parasite are killed by these drugs. Prevention involves inhibiting exposure of chickens to wild birds and regular removal of infested litter.

Feather and Leg Mites

These parasites cause chickens to pull out feathers and cause thickening of the scales on the legs. Mites are visible on scrapings but not with the naked eye. Conditions may be treated by dipping the affected part in a parasiticide or by applying mineral or vegetable oil. Prevention involves inhibiting exposure of chickens to wild birds. In small flocks with ongoing problems, culling of affected birds might be considered.

Red Mites and Northern Fowl Mites

These are blood-sucking mites that may transmit diseases including fowl cholera. The grey or red mites may be visible to the naked eye. Affected birds are restless and may have pale combs and wattles. Young birds may die from anemia. Control of mites in the environment and on the birds is vital for treatment and control. Pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates may be used, and other treatments include use of citrus extracts, mineral oil, and vegetable oil, or hanging cotton bags of sulfur dust in areas where the birds will rub against them. The environment must be thoroughly cleaned and fumigated. Cracks in the environment should be filled in and the birds and environment regularly monitored so disease can be controlled before birds are severely affected.

Internal Parasite Control

Internal parasites found in birds include:

- Coccidia

- Gapeworm

- Roundworms

- Cecal worm

- Tapeworm

- Hairworms or capillary worms

Coccidia

Coccidia are protozoan parasites. Various species of coccidia infect different regions of the intestinal tract. Affected chickens are depressed, and have ruffled feathers and poor appetite. They may have diarrhea and show depigmentation. Chickens commonly are provided with coccidiostatic drugs, such as sulphonamides or amprolium, in their feed or water.

Gapeworm

Syngamus trachea is a nematode parasite that infects the trachea of chickens. Infection is via the oral route by ingestion of snails, invertebrates such as earthworms or slugs, or by direct ingestion of gapeworm eggs. The condition is more common in birds maintained on soil or kept on pasture. The birds stand with their mouths agape and show dyspnea and loss of appetite. The condition is treated and prevented by administration of drugs such as flubendazole in feed.

Roundworms

Roundworms are nematodes of the Ascaridia species. Infection is via ingestion of roundworm eggs. Affected birds may be asymptomatic or may show poor growth, depression, and diarrhea. Treatment with various anthelmintics is curative. Prevention involves keeping feeders and waterers clean of droppings and rotating on which pastures birds are housed.

Cecal Worm

Heterakis gallinarum is a nematode that infests the ceca of chickens that feed off the ground. The worm itself is not that pathogenic but it may carry a protozoan parasite, Histomonas meleagridis, that causes blackhead disease. Transmission of cecal worms may be by direct ingestion of worm eggs or by ingestion of earthworms that have ingested the eggs. Treatment is possible using various anthelmintic drugs. Chickens may be housed on hard surfaces or hardware cloth placed over soil to prevent ingestion of earthworms.

Tapeworm

Tapeworms are regularly transmitted through invertebrate hosts such as earthworms or beetles and are therefore more common in birds housed on soil. Most birds show no clinical signs of disease but may show lack of weight gain or unthriftiness. Treatment with various drugs is possible but care must be taken to evaluate withdrawal times.

Hairworms or Capillary Worms

Hairworms are nematodes of Capillaria species that may infest the esophagus or crop. Infection is via ingestion of eggs; transmission through ingestion of earthworms also is possible. Most birds show no clinical signs but birds may show unthriftiness or die acutely. Treatment is with anthelmintic drugs. Prevention is through control of exposure to earthworms and thorough cleaning of the environment.

Behavior

Aggression, including pecking out the feathers or pecking at the vent of another bird, are not uncommon behavior problems in flocks of chickens. Any underlying causes of stress including overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and presence of disease, should be identified and addressed. Observation of the flock may identify one individual that is particularly aggressive; that individual may need to be removed. Beak trimming may prevent the problem but does not address underlying stresses and is considered unethical in some countries.

Backyard birds value enrichment. Chickens will spend up to 80% of their time foraging and if they are not given ways to forage and exercise, behavioral problems will develop. Physical forms of enrichment include changes in the environment (for example, creating areas for birds to perch or fly to such as arrangements of logs and branches) and dust baths (shallow pans of sand / soil birds roll around in as a way to clean their feathers and control parasites). Nutritional forms of enrichment include anything that makes them work for their food, such as pushing a stick through an apple and sticking it into the ground for them to peck at, making a hole through a cabbage and hanging it up for them to peck at, freezing fruits and vegetables in water in a pan and then turning it out – this is a particularly good form of enrichment on hot summer days – or dropping a pumpkin from a height and letting the birds find all of the seeds and broken bits.

Biosecurity

Diseases of concern that can be passed from chickens to people include bacterial diseases such as salmonellosis, psittacosis, and tuberculosis; viral diseases such as influenza; fungal diseases such as histoplasmosis; and parasitic diseases such as giardiasis. Humans can decrease likelihood of contracting disease from chickens by wearing dedicated clothing to clean, feed, or handle the chickens; always washing hands after handling birds or equipment used with the birds; never eating or drinking in the area where the birds roam and never allowing birds into areas where human food and drink is prepared or consumed; and minimizing contact of live birds with the very old, the very young, and any immunocompromised people. The CDC has recognized a series of Salmonella outbreaks in backyard chickens since 2015. They reported the following in 2019 regarding these outbreaks:

- There have been 1003 ill people reported from 49 states; 175 of these people have been hospitalized. Two deaths have been reported, one in Ohio and one in Texas. Most people infected with Salmonella develop diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps, are ill for 4-7 days, and recover without treatment.

- An increase in Salmonella infection linked to live poultry usually is seen in the spring and summer, when more people are purchasing chicks. People who got sick in the 2019 outbreak reported getting chicks from places such as agricultural stores, websites, and hatcheries.

- People can get sick from Salmonella after touching poultry or the places where they live and roam. Birds carrying the bacteria may appear healthy and clean.

The following are their recommendations for backyard flocks and their owners:

- Do not snuggle with or kiss birds or touch them anywhere near your mouth.

- Do not permit poultry into the house.

- Remember that backyard poultry are not like family dogs, no matter how much you love them.

Some clients may ask whether or not they can slaughter their chickens when they are no longer laying. Live slaughter is not permitted at a residence anywhere in the Twin Cities. There are processors to which you can refer these clients, for example, Long Cheng – Hmong Livestock and Meat Processing plant in South Saint Paul.

Nutrition

It is recommended to feed a commercial ration to ensure proper nutrient balance. Make sure that young birds are fed a starter or grower ration and not a layer ration, which is much higher in calcium and could cause improper bone growth or renal failure if fed to young birds. Laying hens must be fed a layer ration and can also be provided with supplemental calcium. Birds can be provided with scratch grains (cracked, rolled or whole corn, oats, barley, or wheat) but this should be less than 10% of the total food provided daily. Grains may be soaked to make them easier to digest. Grit also may be provided if scratch grains are offered, to help birds break down these grains. Birds on grass or pasture also may eat grass and insects. Other sources of food for chickens include greens (fruits and vegetables) and mats of oats or wheat grass. Chickens will also eat mice (they can be good mousers in a farm setting) and frogs.

All feed must be maintained in containers that are airtight and watertight and that cannot be accessed by rodents.

Fresh water must be available at all times and in winter, care must be taken that water does not freeze.

*

Caged Birds

Caged Birds

Unique Anatomy – External

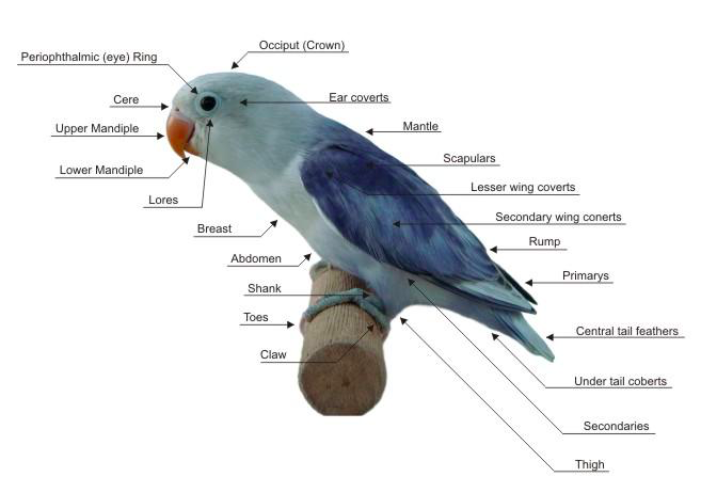

Many caged birds are parrot-like, but you also may work with finches, doves, and other types of caged birds.

Two specific parts of the head we talk about in caged birds are the lores and the cere. The lores are the spaces between the top of the beak and the eye. The cere is a fleshy mass at the top of the beak within which the nostrils are located. All birds have lores and a cere but the cere is especially prominent in psittacines. Species of birds show differences in size and structure of the beak dependent on their primary diet.

Unique Anatomy – Internal

Internal anatomy of caged birds is generally very similar to that of chickens with the exception of the reproductive tract. Depending on the species, it may be unilateral (as in chickens) or bilateral. In most species of caged birds, females have a unilateral reproductive tract on the left side. Knowledge of specifics of the reproductive tract is valuable as direct observation of the gonad of a bird by laparoscopy (surgical sexing) is one method of determining sex of birds from species that are not sexually dimorphic. DNA testing to determine sex also is possible. Here is some basic information about sexing of caged birds.

Specifics of anatomy and other information about caged birds can be found in the Manual of Exotic Pet Practice, pp 250-298.

Housing

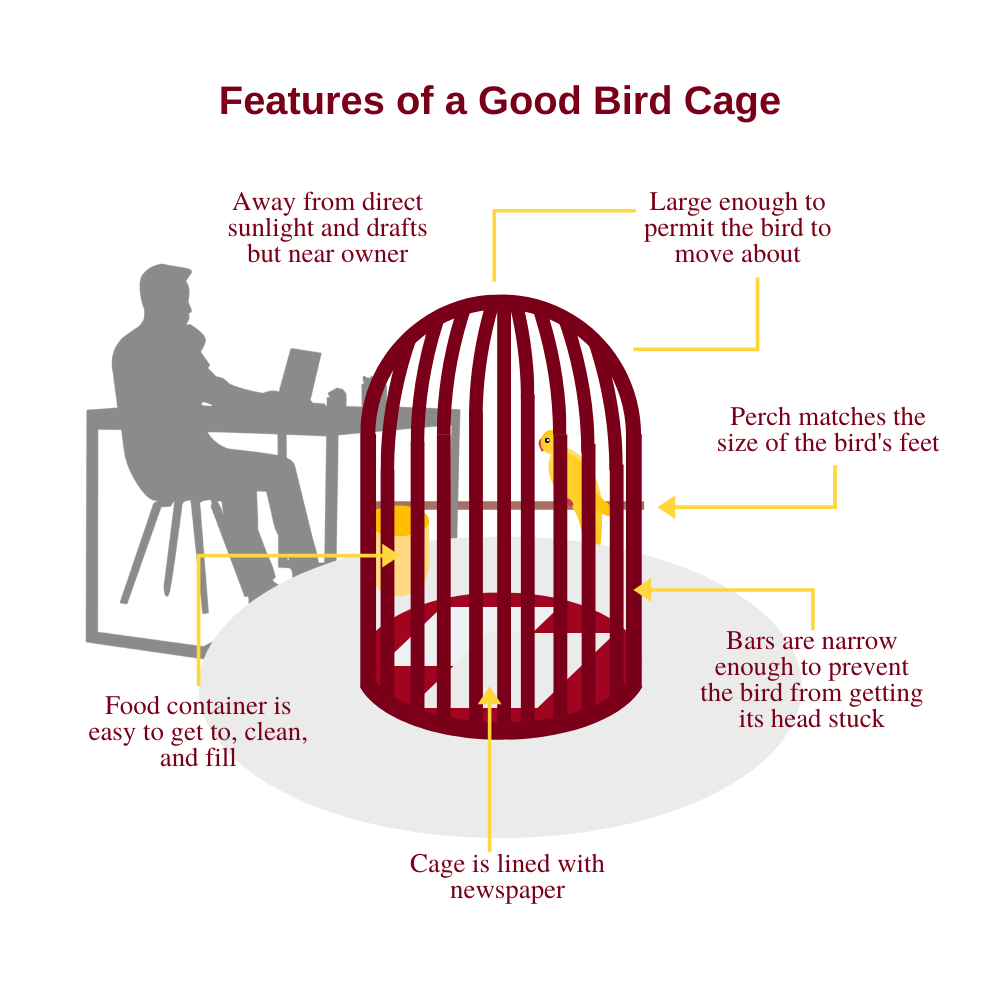

Most companion birds will be caged for the majority of the day. The cage should be placed away from direct sunlight and drafts. Exposure to natural light is important in some species of birds as it may alter molting, egg-laying, and singing behaviors. Many birds appreciate placement of the cage where they can see and interact with their owners. Cages generally should not be put in a kitchen or in any area of the house where chemicals or any other products that give off strong vapors are used or stored. Cages must be large enough to permit the bird to move about and spread its wings. The bars of the cage may be made of a variety of metals and may or may not be painted / powder-coated. Birds often chew at their enclosures so only non-toxic and durable products should be used. Bars of the cage should be narrow enough to prevent the bird from sticking its head through and getting caught. The cage should be easy to clean completely, with water and food containers that can easily be filled and an easy way for the owner to clean the floor of the cage. Cages often are lined with some sort of disposable material, such as newspaper, to facilitate removal of feces; this should be changed at least every 2-3 days. Any spilled seed or seed hulls should also be cleaned from the cage every 2-3 days to prevent insect infestation. Perches should be appropriate for the size of the bird’s feet and should be cleanable. Any toys or other enrichment should be appropriate for the size of the bird. For example, toys for budgerigars should be not given to large parrots, who may chew them apart and ingest small pieces.

Vaccinations and Disease Control

While there are a variety of viral diseases that can infect caged birds, the only one for which a vaccine is available is polyomavirus. This disease causes death in birds ≤ 4 months of age. Prevalence of the virus in adult birds, who are asymptomatic, is considered to be high so there may be little use in vaccinating birds other than those used for breeding or in facilities with a known problem.

Parasite Control

Caged birds rarely can be infected with internal parasites including roundworms, tapeworms, and Giardia sp. Intestinal parasites can be identified by fecal flotation or direct inspection and are treated as in other species. More commonly in birds, parasite concerns are due to infestation with external parasites, usually mites causing feather picking and hyperkeratosis of the beak and legs. Mites can be identified by direct inspection or by skin scraping or by microscopic evaluation of skin and feather debris collected with cellophane tape. Mites are treated on the bird and in its environment with sprays or other direct formulations.

Behavior

See Behavior chapter.

Biosecurity

There are very few zoonotic diseases of concern. Psittacosis (Chlamydia [Chlamydophila] psittaci) is the most common, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the United States annually. Affected birds generally are not clinically ill.

Nutrition

All birds require a source of clean water at all times. Nutrition varies with the species of birds, as some require primarily a seed-based diet (for example, canaries) and others do better with a pelleted diet and fresh fruits and vegetables (for example, budgerigars). Fruit should be offered no more than 2-3 times weekly. Dark green, red, and orange vegetables can be offered daily. Fresh fruits and vegetables should be offered in a separate dish from pelleted food; pelleted food can be available at all times but the fruits and vegetables should be offered for only 30-60 minutes and then removed to prevent spoiling. Birds should never be given avocadoes, onions, garlic, fruit pits or seeds, high-sugar or high-fat foods, or chocolate. Seeds or pellets should be purchased as fresh as possible to minimize loss of nutrients in storage and should be stored to prevent infiltration of insects, especially seed moths. Most caged birds do not require a calcium supplement unless they chronically lay eggs, but calcium supplementation in the form of cuttlebone is inexpensive and also provides enrichment.

Fish

Fish

Unique Anatomy and Classification

There are over 20,000 species of fish and over 1000 have been kept in captivity. Fish can be separated into fresh water, brackish water, and salt water species. Among the freshwater fish, there are temperate and tropical species. Temperate species are sport or game fish, such as sturgeon, pike, walleye, bass, trout, sunfish, and eels. These generally are not kept as pets. In Minnesota, game fish can be kept in a tank legally if they are purchased from a dealer that is licensed by the Department of Natural Resources. The fish maintained in the tank count toward the state angling possession limit for that species.

Freshwater tropical fish are those most commonly maintained in home fish tanks.

| FAMILY | COMMON EXAMPLES |

| Characins | Tetras |

| Cyprinids | Goldfish, carp (koi are an ornamental mutation of carp) |

| Catfish | Catfish |

| Killifish | — |

| Rainbowfishes | — |

| Gouramies | Bettas |

| Livebearers | Mollies, Guppies |

| Cichlids | Angelfish |

Bony fishes are covered with scales and an overlying mucous coat. These serve to protect the fish from trauma and from invasion of pathogens. The scales also provide camouflage or are used for signaling behavior within or between species. When handling fish, it is good to minimize loss of scales or mucous.

Fish have paired pectoral and pelvic fins, and single dorsal, anal, and caudal fins. The dorsal fin is made of two parts in some species. Fins are used for steering, balancing, and braking.

The primary respiratory organs are the gills. The gills are covered by the bony operculum. The gills absorb oxygen, excrete ammonia and carbon dioxide, and regulate absorption and excretion of ions and water. Fish have a simple 2-chambered heart. The lateral line is a mechanosensory structure that permits the fish to sense changes in sound waves and water pressure. There is great variation in the gastrointestinal tract of fish by species. Carnivorous species have a much shorter GI tract than do herbivorous species. Not all species have a stomach. Some species have pyloric cecae that secrete digestive enzymes. Fish have a large liver and a single large kidney with anterior and posterior segments. Another abdominal organ is the swim bladder or air bladder; this is a gas-filled single or double sac that enables fish to maintain depth without expending energy by swimming.

Housing

The environment provided for fish is a miniature ecosystem within which the fish, the water, the substrate, and anything else added to the tank all play a part. Tanks are preferred to bowls for fish as it is easier to create a stable environment for the fish in a larger volume of water. In general, larger tanks are better for the fish than are smaller tanks. Required temperature in the tank varies with the species of fish. Some require very warm water but that is not true of all tropical fish. Fish can tolerate a variation in temperature of about 10°F. Type of light required again varies by species but in general, full spectrum fairly bright light with a 12-hour dark:light cycle is appropriate. Filtration of the water to remove wastes is required. The filter often also contains a system for aeration of water to ensure oxygenation. The substrate in the tank is part of the overall ecosystem. Gravel is easy to clean. Development of a healthy bacterial community within the tank is important and can be managed either with artificial introduction of bacteria (often through a filtering mechanism) or by permitting development of a fine sediment component to the substrate. Addition of artificial plants, tiny deep-sea divers, treasure chests and other inert objects provide places for fish to hide. Make sure they are approved for use in fish tanks so no unexpected compounds are added to the water and do not add so many that it overcrowds the tank. Live plants are more work to establish in the tank but provide shelter and security for the fish, add oxygen to the water, and compete with algae for nutrients, keeping down the development of algae within the tank. Algae also can be controlled by adding an algae-eating species of fish or snail to the tank.

High water quality is vital for health of the fish. Some pet stores provide free water quality testing. At-home kits can be purchased and commercial laboratories also provide water testing. Components of concern are concentration of waste products (ammonia, nitrites, nitrates), pH, and oxygenation. New tanks should be tested daily until the system stabilizes. Fish should be added very gradually to new tanks and stabilization permitted before new introductions. If a tank is set up with a large number of fish at once, acute mortality of all fish may result. In established tanks, 10-20% of the water should be replaced every 1-3 weeks and water quality should be evaluated intermittently.

Nutrition

Fish may be herbivores, omnivores, or carnivores. Most fish require a high percentage of protein in their diet and need dietary fat as a source of energy. Fish digest carbohydrates poorly and require very little carbohydrate in their diet. Fish must be fed food that is appropriate for their species.

Vaccinations and disease control

Vaccinations are not commonly used to control disease in hobby fish tanks; vaccines are used in some commercial fish farming operations. Discussion of fish farming is beyond the scope of this course.

Parasite control

Preventive diagnosis and treatment of parasites is rarely done in hobby fish tanks except at the time of introduction to the tank (see Biosecurity).

Behavior

Fish may hide, dart around quickly, or spend time on the bottom of the tank as normal behaviors. Fish may fight and some fish naturally eat other fish. Attention must be paid to which species will not readily co-exist in a tank. Fish acting listless, swimming erratically, or gasping at the surface may be suffering from poor water quality or illness.

Biosecurity

New fish should be quarantined before being added to the tank. Length of quarantine varies with where the fish were purchased or captured; wild-caught fish are more likely to harbor parasites or infectious diseases. Fish should be checked for external parasites and other signs of disease and potentially treated for internal parasites before being added to a tank.

*

Reptiles

Reptiles

Many states prohibit ownership of venomous reptiles and large constricting snakes.

Many of the concerns we see as veterinarians are because reptiles are not fed and housed properly. A colleague from the class of 2022 offers the following suggestions to pass along to clients who tell you they are interested in getting a reptile as a pet:

- It is widely reported that the majority of pet reptiles (75-90%) die within the first year after purchase due to poor husbandry. Thoroughly research your reptile of interest before bringing them home and have their habitat ready to go before you purchase your new pet.

- Find a veterinarian who will see your reptile before purchase. In many rural areas, there are few to no veterinarians readily available with training and equipment or interest in caring for pet reptiles. Reptiles, like all pets, benefit from regular visits to a veterinarian.

- The majority of the reptile cases seen by veterinarians have problems due to inadequate husbandry. When you take your reptile to a veterinarian, be prepared to answer questions about the ambient temperature, lighting sources, humidity level, and feeding protocol you use.

- It was once widely believed that reptiles could be euthanized at home by putting them in the freezer. It has been found that this is actually a very painful process for the reptile and is not considered an appropriate form of euthanasia due to animal welfare concerns. If you believe your reptile needs to be euthanized, that should be done by a veterinarian.

Unique Anatomy and Classification

The reptiles are a diverse group of animals. There are four orders of reptiles. The order Testudines includes turtles and tortoises. The order Squamata includes the suborders Serpentes (snakes) and Lacertilia (lizards). The order Crocodilia includes crocodiles, alligators, caimans, and gavials. The order Rhynchocephalia contains one or two species of tuatara from New Zealand. Most pet reptiles are from the orders Testudines and Squamata and that information will be the focus of this chapter.

All animals have a glottis. In humans and most mammals, it is the areas within the larynx where the vocal cords are located. In birds, it is basically just the location caudal to the tongue. Reptiles and amphibians have a glottis in that same location. Neither birds, reptiles, nor amphibians have an epiglottis. Some species of amphibians (for example, some frogs) breathe and vocalize using their glottis. Some species of reptiles (for example, snakes) can move their glottis to permit them to breathe while slowly ingesting large prey. They have a trachea that bifurcates into two bronchi and from those into two lungs. Reptiles do not have a diaphragm but do have ribs and breathing is controlled by the intercostal muscles with assistance from the muscles of the trunk and abdomen and smooth muscle in the lungs. There are significant variations in the cardiorespiratory tracts of underwater species.

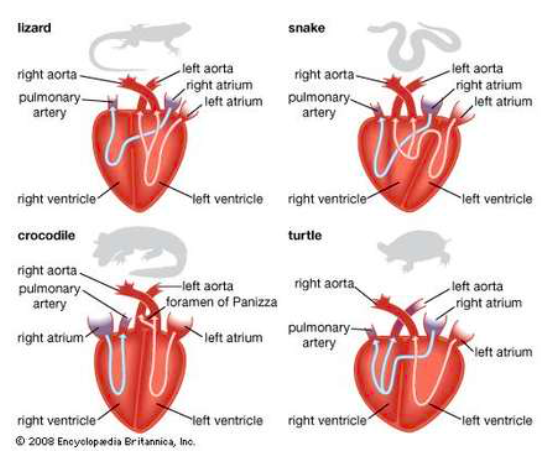

Reptiles are ectothermic (cold-blooded; depending on external heat sources to regulate body temperature). Like amphibians, reptiles have a preferred optimal body temperature that alters cardiac and respiratory function. This in turn will alter the absorption, metabolism, distribution, and excretion of drugs. Squamates (lizards) and chelonians (turtles and tortoises) have a three-chambered heart with a single ventricle; this ventricle does contain an incomplete septum that can permit the heart to function as if it has four chambers. Functionally they have a dual system that always has a potential of mixing oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. Crocodilia have a 4-chambered heart.

Reptiles also have a renal portal system where blood from the caudal half of the animal (dorsal body wall, hind limbs, tail, urinary bladder, cloaca and reproductive organs) passes through the kidneys prior to returning to circulation. This allows for tubular excretion of nitrogenous waste during dehydration. This is of clinical significance when administering drugs.

All reptiles naturally are covered with scales. Some reptiles also have a specialized feature called osteoderms, which are bony deposits located within their scales or skin. This is of special consideration during imaging, surgery, and injections. Some reptiles have been selectively bred to be scaleless, and extra care is required for these animals as they are more sensitive to dehydration and temperature fluctuations. With reptiles and amphibians, different color variations have been selectively bred and are referred to as morphs in the hobby. The care for these animals is often the same, but there can be genetic diseases that are strongly linked to certain morphs.

Snakes and lizards have teeth and may have more than one row of teeth on the maxilla and mandible. Tortoises and turtles do not have teeth and instead have a hard beak used for pulling apart their food; an appropriate diet is important to prevent beak overgrowth. Reptiles generally do not chew their food. Species that swallow their food whole have a highly distensible esophagus. Reptiles do have ureters and a urinary bladder and do produce liquid waste. Liquid and solid waste both are passed through the cloaca.

Reptiles may or may not have eyelids. In general, turtles and lizards have eyelids but some geckos do not. Snake eyes are protected with a transparent scale, called a spectacle, which is replaced when snakes shed. The tongue-flicking behavior of snakes and lizards reflects the use of the tongue to capture chemical cues from the environment that are then applied to the animal’s vomeronasal (Jacobson’s) organ to permit them to identify prey and dangers.

Snakes shed their scales in a normal process called ecdysis. Snakes have small overlapping scales on the dorsum and sides and have ladder-like short, wide scales on their ventrum, called scutes. New scales form over the entire animal under the old scales. Lymphatic fluid accumulates between the new and old scales, dulling the appearance of the skin and markings, and making the spectacles (the scales over the eyes) opaque. The skin clears about 3-4 days before shedding begins. The snake will rub to start the shed and generally will shed the whole skin in one piece.

Specifics of anatomy and other information about all orders of reptiles can be found in the Manual of Exotic Pet Practice, pp 112-249.

Housing

Reptiles are solitary animals and prefer to be alone. A majority will fight or resource guard if another animal is present, especially if it is of the same sex. Sometimes this fighting will result in death or serious injury. Having more than one animal in the same enclosure causes undue stress on both, but especially on the less dominant animal. For these reasons, reptiles should be individually housed.

Nearly all reptiles need to be kept in enclosures with tight-fitting lids, with either weights or a lock to prevent escape. A screened lid is often used to permit ventilation, and can be partially covered to aide in proper humidity. Glass tanks work well for smaller animals. Larger animals, however, may require specially built structures. Many commercial reptile cages are made of plastic or glass making them easy to clean and sanitize. Cages need to be cleaned frequently to avoid buildup of waste and bacteria. Chlorine bleach solutions can be used for disinfection, however, cages need to be thoroughly rinsed and dried before the animals are returned to the environment. The size and shape of the habitat is dependent on the species, number of animals, activity requirements, and necessary enrichments. For example, a tree-dwelling (arboreal) snake requires a higher enclosure than a burrowing (fossorial) snake.

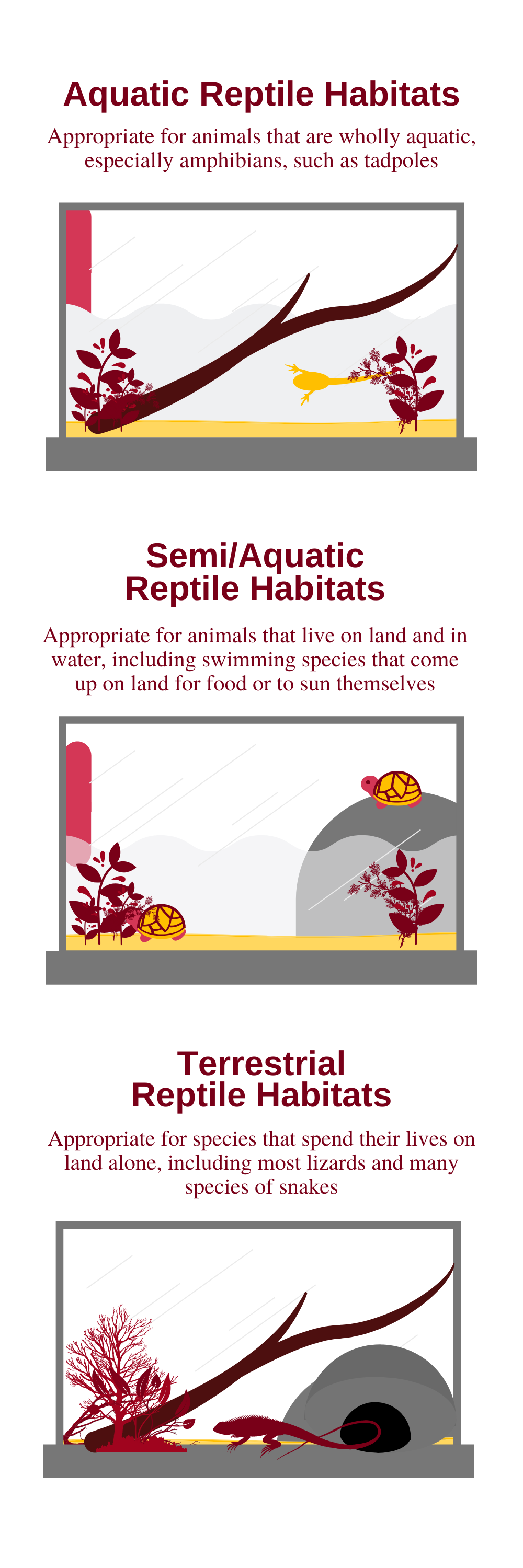

The best guide for reptile habitat is to create one that closely mirrors its natural environment, including considerations of appropriate temperature and humidity. There are three types of habitats that meet the needs of most reptiles and amphibians. Aquatic habitats are appropriate for animals that are wholly aquatic. Semi-aquatic habitats are appropriate for animals that live on land and in water. They may be swimming species that come up on land for food or to sun themselves. Terrestrial habitats are appropriate for species that spend their lives on land.

Aquatic Habitats

Very few reptiles are fully aquatic, but many amphibians are fully aquatic during their larval stage of life. A typical setup includes a filtration and aeration system. This is especially important for tadpoles that cannot breathe air at the water surface. Mudpuppies prefer well-aerated tanks in which they can remain on the bottom and use their gills. Filtration is important because amphibians, like fish, generate ammonia as a waste product. Turtles are especially dirty, and require double the filtration power. Aquariums without filtration systems will need water changes every 2-3 days to prevent buildup of excrement and loss of oxygen. Substrate that cannot be ingested is ideal for the bottom of the tank. Large river stones or slate slabs are much better than sand or gravel, as there is no risk of impaction. Tap water must be treated before adding it to the tank as it often contains heavy metals in addition to chlorine. Chemicals used to treat the water for fish will work for reptiles and amphibians if the directions are followed. Allowing the water to sit in open containers for 48 hours to allow the chlorine to evaporate will get rid of the chlorine, but not the heavy metals. Plants, rocks, and tree branches provide hiding places and mimic the natural habitat.

Semi-aquatic Habitat

All animals kept in a semi-aquatic habitat need to have access to an area that allows them to leave the water completely and dry off if they so desire. Many turtles do well in a tank that is aquatic but has spots that allow them to exit the water completely and dry off. Depending on the species, you may wish to create a split tank. You can create a split tank by dividing an aquarium with a plexiglass wall, using silicon caulking to make each section water tight. In the dry area, create a terrestrial habitat, ensuring that you use substrate that the animal cannot ingest. Add leaves, bark, branches, and plants to make it more like a natural habitat. Ensure that the animal can easily go between the water and the terrestrial side. The water side should be similar to the aquatic habitat. The water side will need a strong filter with a guard, as the animals often drag substrate into the water.

Terrestrial Habitat

Many of the commonly kept reptiles require a terrestrial habitat. This entails a substrate that the animal cannot ingest, with a shelter and water bowl. Cage decorations such as fake plants and logs can be added to make the animal feel more secure. Be sure to include a bowl of water that the animal can submerge itself in if it so desires. The animal should be able to crawl into and out of the bowl freely.

Reptiles are ectothermic (cold-blooded; depending on external heat sources to regulate body temperature) and so require a heat source. When temperatures are too low, metabolism and activity decrease, leaving animals more susceptible to infections. Heating pads that lie under the tank and heat lamps are recommended. Heating pads should be connected to a thermostat to reach the desired temperature and reduce the risk of thermal burns or fire. Direct sources of heat, for example heat rocks, increase the risk for burns. Timers can be used to provide sufficient light and heat during the day with a decrease in temperature towards nightfall that mimics the natural environment. Aquatic and semiaquatic tanks will also need a way to heat water. A temperature gradient within the tank is important because these animals engage in behavioral thermoregulation to avoid overheating. The heat must be provided in a manner that permits the animal to move towards or away from the heat source to find their preferred optimum temperature zone (POTZ).

The vast majority of reptiles and amphibians will require a UVB light as part of their habitat because very few get enough natural sunlight that is not filtered through glass to permit them to make enough vitamin D to contribute to calcium metabolism.

Humidity must also be addressed as low relative humidity increases risk for dehydration and may impair normal shedding while too high relative humidity may predispose to skin infections. A good way to address humidity is to provide a humid hide. This is a shelter filled with a moist substrate that the animal can access when required, such as before a shed. It can be as simple as a piece of Tupperware filled with damp sphagnum moss with an access hole cut into it. Species from tropical rainforests may need sprinkler or misting systems to replicate daily rainfall of their natural environments.

Fresh water should always be available. Most lizards will drink from a water bowl. Water should be changed daily because some lizards soak in or defecate in their water dishes. Some lizards do not recognize standing water as they lap dew in the wild, like chameleons. These animals should have systems that mist the vegetation in their cages in addition to water bowls. Daily misting can also be done by hand using a spray bottle.

Reptiles should only be kept on a substrate that they are not able to ingest. There are commercial sands available that contain calcium, but these become rock-hard when they have contact with water. Many reptiles suffer from impaction while being kept on substrate that they are able to fit in their mouth like sand or gravel. They are not precise hunters, and oftentimes ingest their substrate as they eat their food. A way to avoid this is by feeding the animals in a separate enclosure that has no substrate. However, some animals may be stressed when fed in a separate container and may be more prone to regurgitation of food (for example, snakes should not be handled immediately after feeding). It also may lead to behavioral concerns as some species are used to hunting in their habitat and so should be provided with food in their enclosure as part of enrichment and promotion of natural behaviors. Finally, some animals will learn to associate being handled and moved to another container with being fed, which may be problematic if they seek food or become aggressive whenever they are handled.

Vaccinations and Disease Control

There are no vaccines recommended for control of infectious disease in reptiles. Any animal that has been kept in captivity should not be released into the wild, as they can transmit foreign diseases to local populations. Only animals raised and licensed for reintroduction should be released into the wild.

Parasite Control

Mites and ticks are not uncommon in wild-caught reptiles and are less common in healthy, captive-raised reptiles. The most common ectoparasitic mite to infest snakes and lizards is the snake mite Ophionyssus natricis. These mites are often vectors for diseases in reptiles and can be hard to eliminate. These mites tend to accumulate in the folds or indentations of the animal and often are found around the eye and the vent. Owners may be able to feel the mites crawling on them after handling their pet, or see the mites themselves; the mites are about the size of ground pepper. Clinical signs include decreased activity and abnormal shedding. Animals often will soak in water more than usual in an attempt to drown the parasites. The dead mites may be found in water dishes. There is a permethrin anti-parasitic agent that is approved for use in reptiles and other drugs, such as ivermectin, also have been shown to be safe and effective in some species. Ticks are readily visible and can be removed by hand or treated with medications as described above. Ticks may be associated with bacterial infections or anemia, which may require treatment as well.

All types of internal parasites are found in reptiles, although some are commonly associated with a given type of reptile. For example, trematodes are most common in turtles and snakes while tapeworms and nematodes are found in all species. Clinical manifestations of disease are most common in animals housed in crowded or unsanitary conditions. Diagnosis is by fecal flotation or direct inspection and treatment varies with the type of parasite identified.

Behavior

Specifics of behavioral concerns in the many species of reptiles will not be addressed. Veterinarians are encouraged to work with owners to ensure they know the normal feeding, shedding / molting, and hibernation / estivation behaviors of their animals, so they can tell the veterinarian if something atypical is happening. It is suggested that the owner keeps a record book of when the animal is fed, what it was fed, what vitamins and minerals were provided, the weight of the animal, when the animal shed, when the animal defecated, and any abnormal behaviors noted.

Biosecurity

In order to prevent parasites like snake mites infecting other animals, it is advised to quarantine all newly acquired animals. The animal should be placed in a quarantine tank, which is the bare minimum of requirements in a simple set-up. This allows for easy observation of the animal and any treatment that it may require. This tank should be isolated away from other animals and cleaned daily after all other cages. The animal should be quarantined for a minimum of 30 days; 60-90 days is ideal.

Transmission of bacteria, most notably Salmonella sp. between reptiles and humans is a very real concern, possible with many species but particularly of concern with small turtles, to the extent that since 1975, sale of turtles less than 4″ has been banned by the FDA. In 2020, the CDC identified an increase in human cases of Salmonella sp in owners of bearded dragons. If possible, the cage and accessories and tools should be cleaned with a 1:10 solution of bleach and water, outside the home if possible. Anyone handling a reptile or any part of its housing, including food and water dishes, should thoroughly wash their hands afterward, ideally not in a kitchen sink or anywhere food for humans is prepared. Children, immunocompromised individuals, and the elderly should be particularly cautious. No one should kiss or snuggle reptiles and everyone who handles or feed reptiles should immediately wash their hands.

Nutrition

There is tremendous variety in diet of reptiles and this may vary with life stage. For example, some lizards that are primarily carnivores or insectivores as juveniles need a primarily herbivorous diet as adults, for example, bearded dragons and iguanas. As an example, in bearded dragons young juveniles typically eat 80% insects and eat 2-3x daily. When they are anywhere from 9 months to 12 months they will transition to eating daily – Adults may only need insects weekly when fully established (after 3 years of age, typically) and adults may only eat 2-3x weekly in general and up to 70% – 90% of the diet may be vegetation – and of that vegetation, 80% should be dark, leafy greens. Failure to change the diet appropriately with age of the animal may result in disease.

All snakes are carnivorous. Since snakes eat whole prey, they often do not have nutritional issues. Their main prey item will be species specific, as some are insectivorous and other will eat such things as lizards, mice, or other snakes. Many snakes kept in captivity have been transitioned to eating such prey items as mice, rats, or rabbits. A snake should not be offered a prey item whose circumference is larger than the thickest part of the snake’s body. A live prey item should never be left with the snake, as snakes do not constrict in defense. Oftentimes, they suffer bite wounds or death from fighting with the prey. Insects may be fed live but other live prey should be avoided as they can kill the snake while defending themselves. Frozen prey can be purchased for feeding. An owner should transition the snake from live prey by offering it freshly killed prey items. There are many resources online on how to transition a snake from live to frozen prey. The snake should defecate after a meal before being fed again; with this provision, young snakes generally can be fed every 2-7 days while adult snakes can be fed every 7-21 days. Some species of snakes, like a ball python, will go for weeks without eating. If the snake begins to lose weight it should be seen by a veterinarian. Snakes that are going to shed will go off feed beforehand and become dull in color. Their eyes will turn cloudy blue when they are close to shedding, which will temporarily blind them. The snake should be left alone at this time.

Each species of reptile has its own unique dietary requirements that often require vitamin and mineral supplementation. This is especially true for tortoises, turtles, and lizards. Many of these supplements are now commercially available and tailored for some species. The frequency and types of supplementation that the animals require will change depending on species, so you will have to search for reputable sources. A good supplement will list what vitamins it provides, but also the source. Some reptiles cannot use vitamins unless they come from the correct source. Most reptiles require a calcium supplement in their diet to prevent metabolic bone disease. To properly use the calcium in their diets, reptiles require vitamin D3. This can be supplemented in the diet but is best provided through natural sunlight that is not filtered through glass or plastic as that eliminates the UVB rays they require. The vast majority of reptiles and amphibians will require a UVB light as part of their habitat because very few get enough natural sunlight that is not filtered through glass to permit them to make enough vitamin D to contribute to calcium metabolism. A reptile UVB bulb should be provided. This bulb will need to be changed every 6 months to make sure it is providing not just light but also the UVB rays that reptiles require to metabolize calcium.

Always research the proper diet for the specific species of animal. For example, animals that are primarily herbivorous should not be fed high-protein dog or cat food, which makes the animal feel full without providing sufficient non-digestible dietary fiber and other components of a plant-based diet. The diet for each species will vary in protein, protein sources, and plant matter. Standard captive raised insects are not nutritionally complete enough for healthy reptiles. These prey items need to be fed a nutritious diet before being fed to a pet reptile. In addition, they should be supplemented, often through dusting with appropriate calcium and vitamins. Iceberg lettuce should be avoided, as it is devoid of nutrients. Spinach should also be avoided, as it binds calcium easily, further increasing risk of metabolic bone disease.

Diet for Lizards, Turtles, and Tortoises

- Protein Sources

- Good staple insects: Dubia roaches, crickets, locusts, mealworms, superworms, earthworms, red worms

- Mice can be given as a treat, but they are high in fat

- Eggs, chicken or quail

- Grocery store smelt

- Feeding goldfish and rosey reds can be dangerous because it blocks thiamine absorption and destroys vitamin B1 in the animal in large quantities

- Plants

- In general dark leafy greens can be a majority of the diet. Yellow, red, and orange vegetables like bell peppers can also be included. A good diet is often composed of a mix of collard greens, beet greens, mustard greens, broccoli, turnip greens, alfalfa hay, bok choy, kale, parsley, Swiss chard, watercress, clover, red or green cabbage, savory, cilantro, kohlrabi, bell peppers, green beans, escarole, and dandelion. Fruit should be given sparingly as a treat, as it is a poor source of minerals.

*

Amphibians

Amphibians

Unique Anatomy and Classification

There are three orders of amphibians. The order Caudata is made up of newts and salamanders. The order Anura includes frogs and toads. The larval form is called a pollywog or tadpole. Tadpoles have tails and internal gills. Metamorphosis is a sudden transition from this larval stage to the adult stage. Frogs have smooth skin and long hind legs adapted for swimming. Toads do not have smooth skin and have stubby bodies and short back legs. Frogs and toads are tailless amphibians. The order Gymnophiona consists of caecilians, burrowing amphibians that resemble earthworms or snakes.

Amphibians spend their larval phase in water and the adult phase partially or completely on land. Their skin is thin and moist. Amphibians can absorb oxygen through their skin by diffusion. Amphibians do not have a diaphragm or ribs but do have sac-like lungs. Air can be drawn into the lungs through contraction of the floor of the mouth.

Amphibians are ectothermic (cold-blooded; depending on external heat sources to regulate body temperature). They have a three-chambered heart with a single ventricle.

Amphibians do not have scales. They can absorb water through their skin and lose water from the skin through evaporation. Amphibians that live in drier areas have thicker skin that helps them conserve moisture. The skin of most amphibians is covered with fluid-secreting glands that produce a slimy mucus. The mucus helps conserve moisture, prevents too much water from being absorbed into the body, and helps the animal escape predators. Some amphibians also have toxin-producing glands in their skin. The toxins produced can be deadly to predators, including humans.

Tongues of different kinds of amphibians vary considerably. Some have alterations of the hyoid apparatus that permit their long, sticky tongues to be ejected to capture prey and some do not have tongues at all. Amphibians either have no teeth or have very small teeth in the upper jaw only. They crush their prey with their jaws and swallow it whole.

Unlike birds, amphibians do have ureters and a urinary bladder and do produce liquid waste. Liquid and solid waste both are passed through the cloaca.

Amphibians generally do not have good eyesite. Their lens is fixed, decreasing ability to focus. They do not have external eyelids and instead protect the globe of the eye by pulling it back into the socket and covering it with a third eyelid, or nictitating membrane.

Specifics of anatomy and other information about amphibians can be found in the Manual of Exotic Pet Practice, pp 73-111.

Housing

Amphibian housing is similar to the housing in the above reptile section. Most should be kept individually as well to prevent stress and cannibalization of smaller cage mates. There is a wide variety of species of amphibians and an accompanying wide variety of appropriate habitats. The best guide for an amphibian habitat is to create one that closely mirrors its natural environment, including considerations of appropriate temperature and humidity. Amphibians are sensitive to chemicals, so care should be taken to thoroughly wash any décor that is placed within their enclosure. Tap water must be treated before adding it to the tank as it often contains heavy metals in addition to chlorine. Chemicals used to treat the water for fish will work for amphibians if the directions are followed. Allowing the water to sit in open containers for 48 hours to allow the chlorine to evaporate will get rid of the chlorine, but not the heavy metals.

The tank and associated equipment and tools used should occasionally be cleaned with dish soap or a dilute bleach solution. The animals must be removed from the tank and the tank must be thoroughly rinsed with water before the animals are returned. Because amphibians are directly exposed to anything in their environment through their skin, it is vital that the environment be kept scrupulously clean and that the animals not be exposed to chemicals used for cleaning.

Vaccinations and Disease Control

There are no vaccines recommended for control of infectious disease in amphibians.

No animals kept in captivity should be released into the wild. The spread of chytrid fungus, a fungus that is currently causing global amphibian extinction, has been linked to the release/escape of animals from the medical and pet trade into the wild.

Parasite Control

Amphibians can carry internal and external parasites but this is an uncommon concern in pet amphibians. Because many parasites have indirect life cycles, life cycle of the parasite cannot be completed in captive housing so the parasite population dies out. Disease is most commonly seen in stressed or immunocompromised animals, particularly those maintained outside of their POTZ.

Behavior

Specifics of behavioral concerns in the many species of amphibians will not be addressed. Veterinarians are encouraged to work with owners to ensure they know the normal feeding and hibernation behaviors of their animals, so they can tell the veterinarian if something atypical is happening.

Biosecurity

Good general hygiene should offset any concerns about passage of disease from pet amphibians to humans.

Nutrition

Amphibians are carnivores. They eat anything that will fit into their mouths, including smaller amphibians. Immediately separate if fighting occurs. Larger amphibians may consume small birds, mice, and small rodents. Tadpoles and aquatic species feed on vegetation and dead animals in the wild. In an aquarium tadpoles can be fed algae or tadpole powder available from pet stores. They can also be fed boiled lettuce, flake fish food, and fish hatchlings. As they begin to metamorphose into frogs, their diet should change to crickets, mealworms, waxworms, and other insects that are in the recommended food for reptiles. Smaller amphibians can be kept with springtails and isopods, which will clean the cage and also be a source of food. Feeding pelleted reptile food is not recommended. Amphibians are also prone to metabolic bone disease so supplementation with calcium and vitamins is required. Amphibians also are prone to hypovitaminosis A, which causes their tongue to keratinize and inhibits their ability to eat. This is also referred to as Short Tongue Syndrome. Any supplements that they receive should contain vitamin A. Some amphibians can only use vitamin A from select sources, so consult with an expert to figure out the proper supplements for the amphibian in question.

*

Extra Resources

Extra Resources

- Disease control in chickens (National Poultry Improvement Program): (poultryimprovement.org).

- Small and backyard poultry flocks (National Cooperative Extension service: https://poultry.extension.org

- Keeping urban poultry (University of Kentucky): http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/pubs/ASC/ASC241/ASC241.pdf

- Infectious and non-infectious disorders of amphibians: http://www.merckvetmanual.com/exotic-and-laboratory-animals/amphibians

- Infectious and non-infectious disorders of reptiles: http://www.merckvetmanual.com/exotic-and-laboratory-animals/reptiles

- Breathing in birds: https://www.whfreeman.com/BrainHoney/Resource/6716/SitebuilderUploads/Hillis2e/Student%20Resources/Animated%20Tutorials/pol2e_at_3101_Airflow_in_Birds/pol2e_at_3101_Airflow_in_Birds.html

- Laryngotracheitis disease in birds: http://www.veterinaryworld.org/2008/July/Common%20Respiratory%20Diseases%20of%20Poultry.pdf

- Fowl pox: https://www.hyline.com/aspx/redbook/redbook.aspx?s=5&p=35

- Marek’s disease in birds: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/poultry/neoplasms/marek%E2%80%99s-disease-in-poultry

- CDC recommendations around salmonellosis in backyard chicken flocks: https://www.cdc.gov/features/salmonellapoultry/index.html

- Specifics of anatomy and other information about various animals can be found in the Manual of Exotic Pet Practice http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9781416001195