17 Drug Management

Learning Objectives

- Briefly describe drug approval process through the FDA

- Explain use of drugs off-label

- Define a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship

- Explain rules around prescription of drugs

- Briefly explain management of controlled drugs

- Describe appropriate disposal of drugs and why this is important

- Define and explain veterinary feed directives

This information will be repeated in pharmacology and clinical courses. Information provided in this course is intended to be an overview of veterinary drugs to help you understand what you’re seeing in practices and research laboratories and to provide a framework for you as you see this material again in different contexts.

There are many state and federal drug regulations practicing veterinarians are expected to know and follow. Laws change all of the time so it’s good to be aware of which agencies legislate which products and to search for current information as needed on their websites or through the American Veterinary Medical Association.

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

- Minnesota Board of Pharmacy

Consumers and veterinarians are encouraged to report adverse drug experiences. This includes lack of effect of a drug, untoward or unexpected side-effects, and defects of products including poor packaging. Drug concerns are reported to the manufacturer and to the FDA. As noted earlier in the course, vaccine concerns are reported to the USDA. Flea and tick products are pesticides; some are approved by the FDA and others are under the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Designation for FDA or EPA approval is on the label.

*

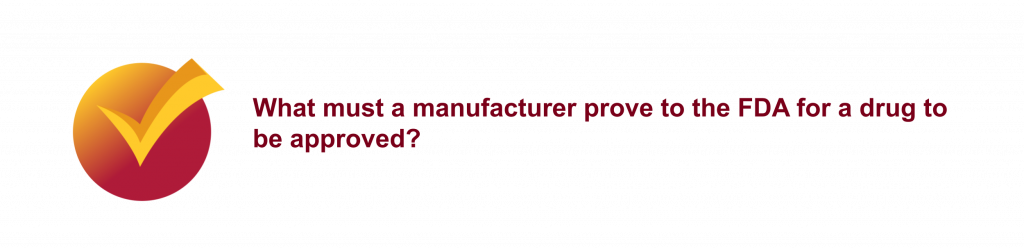

Drug Approval Process

The FDA defines “drugs” as “articles in the United States Pharmacopoeia, official Homeopathic Pharmacopoeia of the United States, or official National Formulary; articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease in man or other animals; and articles other than food intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man other animals.” For a drug to be approved, it must be demonstrated to be safe and effective in the species of interest. Safety includes safety to the animal and any food products derived from that animal, to those people handling the drug, and to the animal’s environment. A drug is defined as effective if it can be demonstrated to consistently do what the labeling claims it will do. For a drug to be approved for a given species, the drug sponsor (usually the manufacturer or holder of the patent) must provide evidence including the drug’s chemistry, composition, manufacturing methods, labeling, effectiveness, adverse effects, and an environmental assessment. If the drug is intended for use in food-producing animals, methods of residue analysis must be described and safe levels for human consumption determined. The FDA rigorously evaluates this evidence and produces a summary document that includes all concerns about the drug. All warnings and precautions from the FDA must be printed on the drug label and consumers are legally required to follow the label.

Drugs may be labeled as prescription-only, over-the-counter, or VFD (see below). The FDA makes this determination based on whether a layperson can use the drug safely and effectively without guidance from a health professional. Veterinary prescription drugs can only be dispensed on the written or verbal order of a licensed veterinarian.

*

Prescribing and Dispensing Prescription Drugs

For a veterinarian to prescribe a drug for a specific animal, a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship must exist. This relationship is defined in each state’s veterinary practice act and generally refers to the veterinarian having specific knowledge of the animal and its environment that permits wise use of drugs for health management. For example, if the veterinarian has not examined the animal for a long period of time or since significant health changes have occurred, a valid relationship cannot exist. The Code of Federal Regulations defines a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship as follows:

“A valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship is one in which: (1) A veterinarian has assumed the responsibility for making medical judgments regarding the health of (an) animal(s) and the need for medical treatment, and the client (the owner of the animal or animals or other caretaker) has agreed to follow the instructions of the veterinarian; (2) There is sufficient knowledge of the animal(s) by the veterinarian to initiate at least a general or preliminary diagnosis of the medical condition of the animal(s); and (3) The practicing veterinarian is readily available for followup in case of adverse reactions or failure of the regimen of therapy. Such a relationship can exist only when the veterinarian has recently seen and is personally acquainted with the keeping and care of the animal(s) by virtue of examination of the animal(s), and/or by medically appropriate and timely visits to the premises where the animal(s) are kept.”

According to Minnesota Statute, a veterinarian may issue a prescription or other veterinary authorization by oral or written communication to the dispenser, or by computer connection. If the communication is oral, the veterinarian must enter it into the patient’s record. The dispenser must record the veterinarian’s prescription or other veterinary authorization within 72 hours. Veterinarians may be asked by large pharmacies for a NPI number and we cannot legally have these. This is the National Prescriber Information number that is given to physicians for Medicare. We can only prescribe for animals, who cannot be on Medicare, so we cannot have this number. Similarly, large pharmacies may ask veterinarians for their DEA (controlled substance) number and we are not required to provide this unless we are asking for a controlled drug to be dispensed (see below for a discussion of controlled drugs). The only number we can be asked to provide when prescribing a non-controlled drug is our state license number.

A prescription or other veterinary authorization must include:

- Name, address, and, if written, the signature of the prescriber;

- Name and address of the client;

- Identification of the species for which the drug is prescribed or ordered;

- Name, strength, and quantity of the drug;

- Date of issue;

- Directions for use;

- Withdrawal time;

- Expiration date of prescription; and

- Number of authorized refills.

Prescription drugs may be dispensed from the veterinarian’s facility or from a pharmacy. Clinics may not be able to act as pharmacies for each other unless the clinic dispensing the drug is licensed specifically as a pharmacy by the state’s Board of Pharmacy.

The label on the package of prescription-only products must state on the label the following: “Caution: Federal law restricts this drug to use by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian.” Other things that must be on the package label include the recommended dosage, route of administration, quantity or proportion of each active ingredient, names of inactive ingredients, and a lot or control number to permit the drug to be tracked regarding date and site of manufacture. Veterinarians should dispense drugs in appropriate receptacles that maintain the activity of the drug and prevent inappropriate use. For example, some liquids break down when exposed to light and should be dispensed in brown bottles. The label on the drug as dispensed by the veterinarian must include the name and address of the person or facility dispensing the drug, the serial number and date of the order as filled, and name and address of the veterinarian who prescribed the drug, strength of the drug, orders for its use (dosage, route and frequency of administration), and any warnings including withdrawal times.

*

Use of Unapproved Drugs

According to the Animal Health Institute, development and approval of a new drug takes about 7-10 years and costs up to $100 million. Few veterinary drugs will earn the manufacturer back enough money to offset this expense. For this reason, many drugs used in veterinary medicine are not FDA-approved for all relevant species. The FDA maintains information about all drugs approved for animals that is updated monthly. The Animal Medicinal Drug Use Clarification Act of 1994 (AMDUCA) permits the use of unapproved (also called extra label) drugs by veterinarians within a valid veterinarian-client-patient relationship when no approved drug is available for that species, the extra label drug has been shown to be safe and effective, and when the health of the animal or suffering or death may result from failure to treat. Veterinarians are only legally permitted to use drugs that are FDA-approved for use in humans or animals. The client should be informed that the drug that is being used has not been approved by the FDA specifically for use in this species and why it is being used. The FDA can declare some drugs as illegal for extra label use if they deem that drug to pose a threat to public health or if there is no acceptable method for analyzing residues of that drug in food-producing animals. Some drugs are prohibited because of concerns about creating resistant strains of zoonotic pathogens that could be transferred to humans after slaughter of food-producing animals. Drugs cannot be used extra label solely to increase production.

*

Controlled Drugs

Controlled substances are chemicals whose manufacture, distribution, use, and disposal require government oversight. In the United States, drugs are classified by the DEA by abuse potential, medical uses, and safety. A list of controlled drugs can be found here. Be aware that federal legislation is a minimum bar and that many states have their own list of controlled drugs and laws regarding those drugs. The more stringent of these laws (federal versus state) must be followed in the state where you practice.

Management of controlled drugs requires the following:

- Registration

- A designated individual with a DEA number is known as a registrant. Veterinarians need their own DEA number if they are responsible for ordering and maintaining inventory of controlled substances or if they prescribe controlled substances through an outside pharmacy. In a hospital setting, there often is one unit registrant who is responsible for the controlled drugs used by a number of other people. The DEA requires different licenses for different streams of activity – for example, an individual may need one license for drugs used clinically and another license from the DEA for drugs used for research.

- Buying controlled drugs

- Controlled drugs must be purchased by the registrant or by their designee using specific DEA paperwork. Facilities that order many controlled drugs may wish to enroll in the on-line ordering system called CSOS (Controlled Substance Ordering System). Receipt of controlled drugs includes prompt inventory to compare drugs and amounts purchased with those received and placement of controlled drugs into a safe specific to this purpose. This safe must have controlled access to authorized personnel and must be fixed in place so it cannot be removed from the room, building, or vehicle in which it is being kept, even if only temporarily.

- Storage of controlled drugs

- Federal law requires that all controlled substances must be maintained behind at least one lock. Many states require a double lock; this can be a safe within a safe, a safe behind a locked door, or a locked refrigerator in a locked room. At a minimum, these drugs must be kept in a safe that is bolted or otherwise secured to an immovable object. Drugs must be kept in the safe at all times they are not being used. Drugs can be carried in a vehicle but must be transferred in a safe that cannot be removed from that vehicle.

- Record-keeping

- Keeping of meticulous records is vital. Specifics of record-keeping vary by state. All states require that at the time of receipt of drugs, a specific page be created in a drug log showing the following for that specific drug: the name, the strength or concentration, the form (liquid versus tablets, for example), the amount in the container, the number of containers, the date it was received, and from whom the substance was received. As the drug is used, a written record must be kept that verifies disposition of all of that chemical, including date of use, amount used, amount disposed of (if any), amount transferred (if any), and initials of user. Anyone with appropriate training can complete the log but the unit registrant is the party responsible for ongoing inventory of controlled drugs at the facility. All records must be kept for a minimum of 2 years by federal law; state law may require that records be maintained for a longer time. The DEA and appropriate state authorities may ask for records or conduct an inspection at any time.

*

Drug Disposal

The FDA strongly encourages laypeople to dispose of drugs as soon as they are done with them. Keeping prescription drugs in the home creates a risk for accidental or purposeful misuse and inappropriate disposal of drugs, for example, by flushing them down the toilet or putting them in the trash, risks contamination of water. A study published by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in 2021, entitled, “Pharmaceuticals and chemicals of concern in Minnesota lakes“, identified chemicals from medications and land use in all lakes studied and stated the following: “This and several previous investigations of varying size over the past 10 years clearly demonstrate that these “contaminants of emerging concern,” such as antibiotics and antidepressants, the pesticide DEET, alkylphenols, and the disinfectant triclosan are widespread in our lakes, rivers, and streams. Many of these chemicals are endocrine active, mimicking naturally occurring hormones. Concern is growing over the effect these chemicals may have on fish and wildlife and human health at very low concentration.”

Drugs may be collected by a variety of agencies. The DEA holds “National Prescription Drug Take Back Days” in April and October. Examples of sites that collect prescription medications near the veterinary college are the area police departments. Sites do not need to be near a veterinary college or in a large, metropolitan area; the DEA also may authorize local law enforcement agencies and pharmacies to take in drugs for disposal at any time. Some municipalities also offer mail-back programs or drop-boxes. Veterinary clinics are not required to take back drugs for disposal. It is always best to recommend to clients that they take drugs to the local law enforcement (police department or sheriff’s department) or to a local chain pharmacy to dispose of drugs. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency provides information about disposal of unwanted medications as well. The American Veterinary Medical Association provides information for veterinarians and clients about drug disposal.

Drugs may expire in veterinary facilities or clinics may need to dispose of controlled substances. For the latter, you may wish to contact the DEA for specifics in your state. Generally the registrant is authorized to dispose of controlled drugs appropriately; any such disposal must be recorded as described above. Disposal of controlled drugs may be through a specific business known as a reverse distributor or may be done using specific products that neutralize the drug before it is disposed of (examples include RxDestroyer and Cactus Sink). Controlled substances should never be disposed of down a drain or through the sewer system.

*

Veterinary Feed Directives in Major or Minor Species

“A Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) is a written (nonverbal) statement issued by a licensed veterinarian in the course of the veterinarian’s professional practice that authorizes the use of a VFD drug or combination VFD drug in or on animal feed.” The VFD is a component of law managed by the FDA that strives to limit antibiotic use in food-producing animals appropriately. As of January 1, 2017, the law was expanded to control use of antibiotics that are medically important for humans when provided to animals in food, even if that animal is not itself intended for food.

The law is changing over time as there are currently some contradictions. For example, only approved drugs can be used in a VFD but for some of the minor species, such as fish, there are few to no drugs available. While the rules are generally applicable to major species, veterinarians must be aware of rules and the need for antibiotics in minor species as well. Minor species, in this context, are any non-human animals other than cattle, horses, swine, chickens, turkeys, dogs, and cats. The FDA provides guidance regarding use of VFD drugs in minor species. The lack of approved drugs for minor species will be an ongoing concern for us as veterinarians, as our hands are tied if there are no approved drugs and neither we nor our clients can find a suitable alternative. The FDA published warning letters in December 2023 that could lead to legal action against pet stores and websites that sell medications that contain antimicrobial agents that are important in human and veterinary medicine. These primarily are antibiotics supplied for pet fish and caged birds.

*

Veterinary Feed Directive Requirements for Veterinarians – For Veterinary Students

Current information available from the FDA for veterinary students is below, and is required for class and your future.

VFD Drug and Combination VFD Drug

What is a “VFD drug”?

A ”VFD drug” is a drug intended for use in or on animal feed, which is limited to use under the professional supervision of a licensed veterinarian.

What is a “combination VFD drug”?

A “combination VFD drug” is an approved combination of new animal drugs intended for use in or on animal feed under the professional supervision of a licensed veterinarian, and at least one of the new animal drugs in the combination is a VFD drug.

What is a VFD?

A VFD is a written (nonverbal) statement issued by a licensed veterinarian in the course of the veterinarian’s professional practice that authorizes the use of a VFD drug or combination VFD drug in or on an animal feed. This written statement authorizes the client (the owner of the animal or animals or other caretaker) to obtain and use animal feed bearing or containing a VFD drug or combination VFD drug to treat the client’s animals only in accordance with the conditions for use approved, conditionally approved, or indexed by the FDA. A VFD is also referred to as a VFD order.

VFD Drugs and Prescription Drugs

What is the difference between a VFD drug and a prescription (Rx) drug?

FDA approves drugs in these two separate regulatory categories for drugs that require veterinary supervision and oversight for their use. When the drug being approved is for use in or on animal feed (a medicated feed), FDA approves these drugs as a VFD drug. When the drug being approved is not for use in or on animal feed, the drug is approved as a prescription drug.

Why VFD instead of prescription?

When the VFD drug category was created, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (the Act) made it clear that VFD drugs are not prescription drugs. This category was created to provide veterinary supervision without invoking state pharmacy laws for prescription drugs that were unworkable for the distribution of medicated feed.

FDA approves a drug for feed use as Over-the-Counter (OTC) or as VFD.

Veterinary Students and VFD

I don’t plan to practice food animal medicine, why should I learn about VFD?

The law allows any licensed veterinarian to issue a VFD in the course of his or her practice and you may find yourself in a situation that requires one. For example, your pet owner client could ask you to issue a VFD for the flock of his/her backyard chickens.

Veterinary Students and Medicated Feed

What is really important for me to know about medicated feeds in addition to VFD?

- FDA regulates medicated feeds;

- Every use of a drug in feed has to be approved;

- There are three types of products in relation to medicated feed use:

- o Type A medicated article,

- o Type B medicated feed, and

- o Type C medicated feed;

- Type A medicated article and Type B medicated feed can be used only for further manufacture of other products. Only Type C medicated feed can be fed to animals;

- Medicated feeds are approved only as over-the-counter or VFD; they cannot be used under prescription;

- All drugs approved for use in feed are placed in two drug categories on the basis of their potential to create unsafe drug residues. Category I drugs have lower potential for unsafe drug residues than Category II drugs; and

- Finally, extra-label use of medicated feeds is prohibited by law.

How are VFD (blank) orders obtained?

VFD drug sponsors may make the VFD order for their drugs available, or, as a veterinarian, you will be able to create your own VFD.

How do I send a VFD to the feed distributor?

You must send a copy of the VFD to the distributor via hardcopy, facsimile (fax), or other electronic means. If in hardcopy, you are required to send the copy of the VFD to the distributor either directly or through the client. You must keep the original VFD in its original form (electronic or hard copy) and must send a copy to the distributor and client.

Extralabel use (ELU) of VFD feed is not permitted.

Veterinarians’ Responsibilities

- must be licensed to practice veterinary medicine;

- must be operating in the course of the veterinarian’s professional practice and in compliance with all applicable veterinary licensing and practice requirements;

- must write VFD orders in the context of a valid client-patient relationship (VCPR);

- must issue a VFD that is in compliance with the conditions for use approved, conditionally approved, or indexed for the VFD drug or combination VFD drug;

- must prepare and sign a written VFD providing all required information;

- may enter additional discretionary information to more specifically identify the animals to be treated/fed the VFD feed;

- must include required information when a VFD drug is authorized for use in a drug combination that includes more than one VFD drug;

- must restrict or allow the use of the VFD drug in combination with one or more OTC drug(s);

- must provide the feed distributor with a copy of the VFD;

- must provide the client with a copy of the VFD order;

- must retain the original VFD for 2 years, and

- must provide VFD orders for inspection and copying by FDA upon request.

Major and Minor Animal Species

What are “major and minor animal species”?

FDA regulations define cattle, horses, swine, chickens, turkeys, dogs, and cats, as major species. All animal species, other than humans, that are not major species are minor species.

When is a VFD needed for a minor species?

The VFD requirements apply to all VFD drugs for use in major or minor species. One VFD drug is already approved for use in minor species (e.g., florfenicol in aquaculture). Other medicated feed drugs for minor species are expected to convert from their present over-the-counter (OTC) status to VFD (e.g., oxytetracycline in honey bees) and at that time a VFD will be required for their use.

VFD and VCPR, Client

What is required for veterinarian supervision?

The veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR) is the basis of professional supervision. A VFD must be issued by a licensed veterinarian operating in the course of his/her professional practice and in compliance with all applicable veterinary licensing and practice requirements, including issuing the VFD in the context of a veterinarian-client-patient relationship (VCPR).

What VCPR standard applies?

FDA provides a list of states whose VCPR includes the key elements of the federally-defined VCPR and requires a VCPR for the issuance of a VFD. If your state appears on this list you must follow your state VCPR, if your state does not you must follow the federal VCPR as defined in 21 CFR 530.3(i).

Who is the “client” on the VFD?

“Client” is typically the client in the VCPR; the person responsible for the care and feeding of the animals receiving the VFD feed.

What is an “extralabel use” of a VFD drug and is it allowed?

“Extralabel use” (ELU) is defined in FDA’s regulations as actual or intended use of a drug in an animal in a manner that is not in accordance with the approved labeling. For example, feeding the animals a VFD for a duration of time that is different from the duration specified on the label, feeding a VFD formulated with a drug level that is different from what is specified on the label, or feeding a VFD to an animal species different than what is specified on the label would all be considered extralabel uses. Extralabel use of medicated feed, including medicated feed containing a VFD drug or a combination VFD drug, is not permitted.

Reorders (Refills)

When can I authorize a reorder (refill)?

If the drug approval, conditional approval, or index listing expressly allows a reorder (refill) you can authorize up to the permitted number of reorders. If a drug is silent on reorders (refills), then you may not authorize a reorder (refill).

Use of medicated feed is authorized by a VFD not Rx.

A Lawful VFD Has to Be Complete

What do I have to include in a VFD?

You must include the following information on the VFD for it to be lawful:

- veterinarian’s name, address, and telephone number;

- client’s name, business or home address, and telephone number;

- premises at which the animals specified in the VFD are located;

- date of VFD issuance;

- expiration date of the VFD;

- name of the VFD drug(s);

- species and production class of animals to be fed the VFD feed;

- approximate number of animals to be fed the VFD feed by the expiration date of the VFD;

- indication for which the VFD is issued;

- level of VFD drug in the feed and duration of use;

- withdrawal time, special instructions, and cautionary statements necessary for use of the drug in conformance with the approval;

- number of reorders (refills) authorized, if permitted by the drug approval, conditional approval, or index listing;

- statement: “Use of feed containing this veterinary feed directive (VFD) drug in a manner other than as directed on the labeling (extralabel use), is not permitted”;

- an affirmation of intent for combination VFD drugs as described in 21 CFR 558.6(b)(6); and

- veterinarian’s electronic or written signature.

You may also include the following optional information on the VFD:

- a more specific description of the location of the animals (for example, by site, pen, barn, stall, tank, or other descriptor the veterinarian deems appropriate);

- the approximate age range of the animals;

- the approximate weight range of the animals; and

- any other information the veterinarian deems appropriate to identify the animals at issue.

The veterinarian must keep the original VFD for two years.

Substance Abuse

There is a great deal of concern about substance abuse, both direct use of veterinary drugs by veterinary professionals and use by animal owners of drugs dispensed for animals. This concern is greatest for controlled drugs, which often have that designation because of their addictive qualities and subsequent abuse potential. The AVMA has information available to help veterinarians identify vet shoppers, defined by the AVMA as “the practice of soliciting multiple veterinarians under false pretenses to obtain prescriptions for controlled substances”, and minimize drug diversion, defined by the AVMA as “the illegal distribution or abuse of prescription drugs”.

In Minnesota, the Health Professionals Services Program protects the public by providing services for all health care professionals (both human and veterinary medicine) to ensure that drug use does not impair ability of a health provider to provide safe care, and provides confidential counseling and resources for health professionals. Information about this program regularly is provided to veterinarians in Minnesota as they renew their license. A similar program is the Minnesota Veterinary Medical Association (MVMA) Wellness and Peer Assistance Committee. Their mission is the following: “Provides resource information to MVMA members on issues of suicide awareness, chemical dependence, mental health, professional burn-out and compassion fatigue. The members regard it as their responsibility to identify and/or provide assistance to MVMA members in need and to help them resume a well-balanced and healthy life.”

To try to counteract the risks of owners using medications dispensed for animals, the MVMA also has created VetPMP (Veterinary Prescription Monitoring Program), as a way of ensuring that drugs dispensed for a given animal are tracked between clinics, so clients cannot “shop” for controlled substances by going from one clinic to another. This is one of many developing programs to work against the opioid abuse problem in Minnesota and throughout the US.

*

Extra Resources

Extra Resources

- American Veterinary Medical Association: http://www.avma.org

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA): www.fda.gov

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA): www.dea.gov

- Minnesota Board of Pharmacy: https://mn.gov/boards/pharmacy/

- Reporting of adverse drug experiences: https://www.myvetcandy.com/clinicalupdblog/2019/4/3/fda-takes-new-steps-to-increase-access-to-adverse-event-report-data

- The Code of Federal Regulations regarding veterinarian-client-patient relationships: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2017-title21-vol6/pdf/CFR-2017-title21-vol6-sec530-3.pdf

- The Minnesota Statute regarding veterinary prescriptions: https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/?id=156.18

- FDA Green Book – information about drugs approved for use in animals: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/products/approved-animal-drug-products-green-book

- List of controlled drugs: https://www.drugs.com/csa-schedule.html

- Drug disposal information:

- Drop-off sites through local law enforcement offices, or local chain pharmacies: https://www.ci.inver-grove-heights.mn.us/677/Prescription-Drug-Drop-Off

- The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: https://www.pca.state.mn.us/living-green/managing-unwanted-medications

- The American Veterinary Medical Association: https://www.avma.org/KB/Policies/Pages/Best-Management-Practices-for-Pharmaceutical-Disposal.aspx

- FDA guidance regarding use of VFD drugs in minor species: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/development-approval-process/minor-useminor-species

- FDA guidance regarding veterinary feed directive requirements for veterinary students: https://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/ucm455417.htm

- How the Veterinary Feed Directive Will Affect Chicken and Poultry Owners: https://countrysidenetwork.com/daily/poultry/feed-health/how-the-veterinary-feed-directive-will-affect-chicken-poultry-owners/

- Honeybees 101 for Veterinarians: https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/Pages/Honey-Bees-101-Veterinarians.aspx

- Welcome to Honeybees and Veterinarians: https://axon.avma.org/ – Free on-demand webinars free to AVMA members including students

- Welcome to Honeybees: Why They Need a Veterinarian: https://axon.avma.org – Free on-demand webinars free to AVMA members including students

- Use of Veterinary Feed Directive drugs in aquaculture: https://caaquaculture.org/2017/01/06/use-of-veterinary-feed-directive-drugs-in-aquaculture/