7 Care of the Young

Learning Objectives

- Describe variability in need for colostrum by species

- Describe ways to maximize and assess colostrum quality

- List significant milestones in development for small animals and foals

- Discuss management of the dam and facilities to optimize health of newborns

- Describe common procedures performed in neonatal foals, calves, and piglets

*

Colostrum Need by Species

Specific actions may be taken to promote health in young animals. Amount of veterinary intervention varies by species. You will note that there are no notes for small animal; that is because there is little routine prenatal care provided and after giving birth, the bitch and queen care for their puppies and kittens with virtually no veterinary intervention associated with preventive healthcare. Notes for this course will review preventive healthcare in foals, calves, and piglets.

One overarching theme when discussing care of any young animal is the need for them to ingest colostrum. Colostrum is the primary route by which most young animals get maternal antibodies (passive transfer) to protect them from disease before they have a functional immune system. How much antibody transfer occurs is dependent on placentation in that species. There are six possible layers in placentas. Three are always present (fetal endothelium, fetal connective tissue, and fetal epithelium, also known as the chorion). The chorion abuts the uterine tissue of the dam, with varying degrees of penetration into that tissue. In an epitheliochorial placenta, the chorion abuts the dam’s epithelium (6 layers). This is the type of placenta in cattle, horses, and pigs. In some species, cells from the chorion fuse with maternal epithelial cells, creating intermittent or continuous areas with 5 layers. This used to be called a syndesmochorial placenta. Now it is understood that this is a variant of the epitheliochorial placenta, sometimes called a synepitheliochorial placenta. This is seen in sheep and goats and may be seen in cattle. In an endotheliochorial placenta, the chorion abuts the dam’s endothelium (4 layers). This is the type of placenta in dogs and cats. In a hemochorial placenta, the chorion is bathed in the dam’s blood (3 layers). This is the type of placenta in primates and rodents. The big picture is that animals with thicker placentas have reduced access to maternal proteins through the placenta, including antibodies, and are therefore more prone to failure of passive transfer, making them dependent on colostrum to a larger extent than other species. Failure of passive transfer (lack of antibodies needed to protect newborn animals against infectious disease) can occur either because a newborn animal didn’t get antibodies through the placenta while in utero or because they did not get colostrum, the antibody-rich first milk, immediately after birth.

*

Care of Small Animals

Care of Small Animals

Veterinarians do not provide routine veterinary care for puppies and kittens immediately after birth as they do in other species. The chart below provides you with information regarding normal developmental milestones in puppies and kittens. Extensive information about physical examination and common disorders of puppies and kittens is available in the resources folder for this module of the course.

*

Timing of Significant Events in Pediatric Development of Puppies and Kittens

| EVENT | AGE AT OCCURRENCE |

| Umbilical cord dries and falls off | 2 to 3 days |

| Eyelids open | 5 to 14 days |

| External ear canals open | 6 to 14 days |

| Extensor dominance | 5 days |

| Capable of crawling | 7 to 14 days |

| Capable of walking, urinating and defecating spontaneously | 14 to 21 days |

| Hematocrit / RBC number stabilize near that of adult | 8 weeks |

| Renal function nears that of adult | 8 weeks |

| Hepatic function nears that of adult | 4 to 5 months |

*

Care of Foals

Care of Foals

The level of care and degree of intervention for any neonate will vary with the management type and philosophy, and to some extent with the value of the individual offspring. In this section we’ll look at fairly typical care of neonatal foals. Good management of the foal starts prior to birth, with care of the dam integral to optimizing postnatal foal health, and continues with common management procedures and veterinary examination of the neonate.

Management of the Pregnant Mare to Optimize Foal Health

Maximizing Colostral Quality

Even though they become immunocompetent during gestation, while cocooned in the uterus foals are generally not exposed to environmental and common disease-causing pathogens that they will be exposed to after birth. Due to their type of placentation, antibodies from the mare are not transferred prior to birth so the foal is born agammaglobulinemic and naïve regarding protection against potential pathogens they will encounter once born. Their initial circulating antibodies are absorbed from the mare’s colostrum so it is important that the antibody content of colostrum is high in quantity and quality – that is to say that it is directed against organisms the foal is likely to encounter. Two strategies are generally employed to ensure this:

- If the mare is to be moved to a different farm for foaling (this often happens either to have her at a location with more supervision/experience in foaling mares or to have her at the farm where she will be re-bred for the next season), this move should occur at least 4-6 weeks prior to birth. This allows the mare to be exposed to the local microflora and to make use of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) to push antibodies against local flora into colostrum and later to create IgA in milk for continued protection against invasion.

- Vaccinate the mare 4-8 weeks prior to parturition to boost colostral antibodies.

This is a time to use vaccines that will give a systemic (IgG) response in the mare versus a local (IgA) response because we want the serum IgG available for transfer into the colostrum.

Typical vaccines used include those against:

- Tetanus

- Rabies

- Western and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (WEE/EEE)

- West Nile Virus

- Herpes Virus 1 and 4 – or just use EHV-1 and hope for cross-protection

- Influenza

Additional vaccines occasionally used depending on locale/farm conditions and likely pathogen exposure may include:

- Botulism

- Rotavirus

- Streptococcus equi

When giving large numbers of vaccines to a mare it is often considered good practice to give no more than four antigens at one time and to have a 2-4 week break before giving the next group, until the administration of all those desired has been completed. To accomplish this, the vaccines against diseases of lower risk and the vaccines resulting in the most robust antibody response are given earlier, and the “weaker” antigens are given later, usually about 4 weeks prior to foaling. Of those listed above, both tetanus and rabies vaccines are known to give a robust response and thus can be moved to the earlier time. Note that a mare in her first pregnancy may need an initial series of vaccines she has not had previously; in subsequent pregnancies it is most often just a single booster.

Measuring Colostral Quality

As foaling is imminent or immediately following birth of the foal, many larger farms will measure the quality of the colostrum. This is done by measuring specific gravity using a colostrometer or by measuring total solids using a sugar refractometer as a proxy for IgG concentration (Note: regular clinical refractometers used for plasma protein or urine specific gravity DO NOT work). Foals from mares with poor quality colostrum may be targeted for early supplementation from a frozen colostrum bank. Mares with excellent quality colostrum have some stripped out (250-300 ml) and frozen to deposit in the bank.

Mare Anti-RBC Antibody Screening

On larger farms and particularly for mares that have previously had a foal with neonatal isoerythrolysis (antibody-associated break down of red blood cells by the foal shortly after birth and colostrum ingestion), a blood sample is taken from the mare in the last two weeks of gestation to screen for antibodies directed against red cell antigens. Like other animals, horses have blood types and if the mare has antibodies against red cell antigens her foal has inherited (from the sire) it can result is severe red cell lysis once the foal has suckled. These antibodies are concentrated in colostrum and absorbed by the foal. In cases where a mare comes up positive the foal is NOT permitted to suckle her initially but is given colostrum from a safe source. The mare is milked out and the colostrum discarded. This is repeated and the foal not permitted to suck until about 24 hours of life (when the colostrum is gone and the foal’s gut has closed to antibody absorption).

Anthelmintic (dewormer) Administration

On or about the day of parturition the mare is given an anthelmintic (usually ivermectin) to reduce passage of parasites to the foal. A particular parasite targeted by this is Strongyloides westeri, which is transmitted through the milk.

Management and Care of the Newborn Foal

If pregnancy and delivery were normal, the farm staff will observe the foal for normal behaviors and “milestones”. If everything is going well, you, as a veterinarian, will probably see the foal for the first time when it is 12-18 hours old. If things were abnormal at birth or are not progressing as usual, you can expect a call earlier, and in the case of a high risk pregnancy, may be in attendance at birth.

Normal parameters for farm personnel to watch for are:

- Following birth the foal should be vigorous, have good muscle tone, and attain sternal recumbency within 2 minutes (i.e. not stay in lateral).

- A suckle reflex should be present in 10-15 minutes.

- The foal should attempt to stand in 15-30 minutes and achieve standing within 1 hour.

- The foal should nurse the mare’s udder within 2 hours – Note that it is normal for it to try a few other places before it locates the udder!

- Normal behavior is for the foal to nurse about 7 times an hour for about 90 seconds/bout. They should gain about 2-3 lbs/day in weight.

- The foal should pass meconium (first poop, sticky dark tan/orangy stuff) within 4 hours.

- The foal should first urinate in about 4 hours and then keep on doing so. The urine should be pale, not distinctly yellow.

What the farm personnel will/should do:

- Dip the umbilical stump to help prevent ascending infections

- Generally done with dilute chlorhexidine (0.5% = 1 in 4 dilution) or dilute iodine

- Usually repeated several times in the first 24 hours

- Use a syringe case or soaked gauze – they need to dip the umbilical remnant, not the entire ventral abdomen

- Weigh the foal

- Save the placenta for veterinarian to examine

- Plastic bag inside a clean 5 gallon feed pail with lid

- This avoids the common pathological artifact lesionae doggus chewus

- Plastic bag inside a clean 5 gallon feed pail with lid

- On many farms it is usual to give the foal an enema either prophylactically or if no meconium has passed in a few hours. Usually warm soapy water or a commercial “Fleet” enema is used.

Important Newborn Foal Milestones

Some of the vital milestones are summarized as the 1-2-3 rule:

- The foal should be standing within 1 hour

- The foal should have suckled from the mare within 2 hours

- The mare should have passed the placenta within 3 hours

Assuming all this happens and there are no other issues, then the first time the foal is seen by a veterinarian is for the well foal examination.

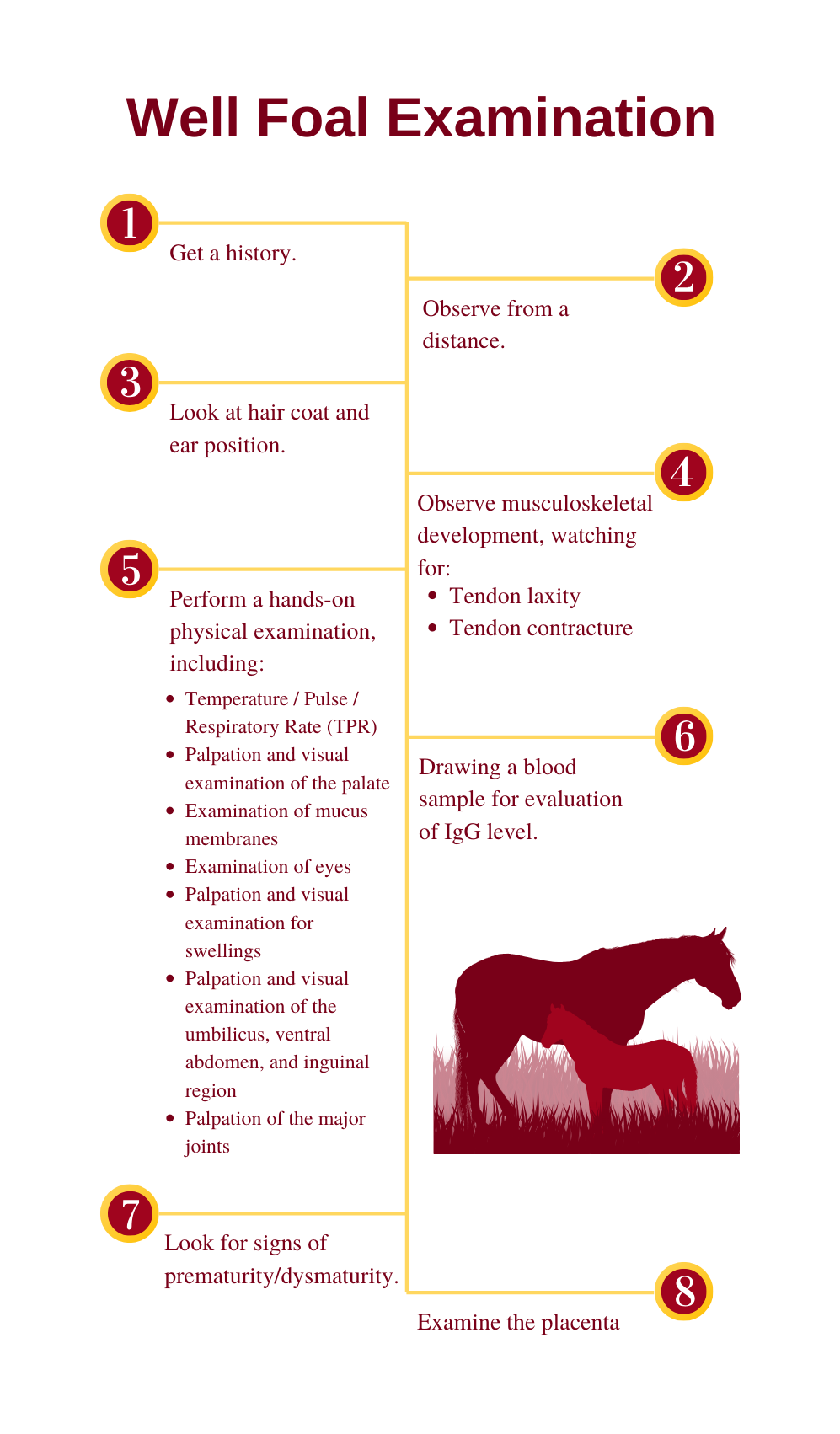

Well Foal Examination

Usually occurs at 12-18 hours of age (but may be out to 24-36 hours on a distant farm), and the veterinarian will:

- Get a history including length of pregnancy, time and length of delivery, and the parameters listed previously (time to stand/nurse/pass meconium)

- Observe from a distance for normal behavior and respiratory effort and character

- Normal foals are active between naps and have slightly jerky movements. Reduced activity and somnolence are signs of a problem as is a distended udder in the mare – usually an indicator that the foal is not nursing.

- Look at hair coat and ear position (silky coat and/or floppy ears are a sign of prematurity/dysmaturity).

- Observe musculoskeletal development, particularly of the limbs, watching for:

- Tendon laxity – fetlocks near/on the ground, toes tipped up, carpus hyperextended

- Tendon laxity is another sign of prematurity/dysmaturity

- Tendon contracture – club foot, upright fetlocks, flexed carpi

- Limb deviations in the mediolateral plane when viewed from in front or behind

- Tendon laxity – fetlocks near/on the ground, toes tipped up, carpus hyperextended

- Perform a hands-on physical examination particularly including:

- Temperature / Pulse / Respiratory Rate (TPR)

- It is normal to auscult a heart murmur for 1-2 days following birth; murmurs or arrhythmias present beyond 4 days after birth need investigating

- Palpation and visual examination of the palate (for cleft palate – additional sign may be milk coming from the nostrils)

- Examination of mucus membranes for normal color and refill and no petechiation (petechiation is a sign of sepsis)

- Examination of eyes for cataract, corneal ulcers or entropion (rolled in eyelashes rubbing on cornea)

- Foals don’t have a reliable menace response (blink as you poke toward their eye) until about 2 weeks of age, so they have to learn to be scared of getting poked in the eye by stuff

- Palpation and visual examination for swellings over the ribs and “clicks” indicative of fracture (birth in the horse is a fairly violent event)

- Palpation and visual examination of the umbilicus, ventral abdomen, and inguinal region for evidence of swelling or herniation

- Palpation of the major joints (carpus, stifles, fetlocks) for effusion

- Joint effusion is usually related to infection in the joint, secondary to septicemia; this would be early to pick it up

- Temperature / Pulse / Respiratory Rate (TPR)

- Drawing a blood sample for evaluation of IgG level (to assess adequacy of passive transfer of colostral antibodies – VITALLY IMPORTANT).

- This is usually performed as a stall side test using a rapid ELISA kit

- Foals with less than adequate levels (<800 mg/dL) get supplemental IgG, usually in the form of IV plasma, because sepsis is a leading cause of foal mortality and foals without adequate IgG levels are much more likely to become septic.

- This is usually performed as a stall side test using a rapid ELISA kit

- Look for signs of prematurity/dysmaturity.

- Foals with these signs that are otherwise doing okay should have carpi and tarsi radiographed to check for cuboidal bone ossification (the small bones that make up the carpus and tarsus), and have activity restricted if these are incompletely formed to avoid crush injuries.

- Examine the placenta

- Is it complete?

- Bits left in the mare promote uterine infection with resultant endotoxemia and laminitis – a very bad deal.

- Are there abnormalities that indicate the foal may deserve a more thorough examination, closer observation or even some prophylactic treatment?

- Placentitis, evidence of premature placental separation, reduced placental size.

- Is it complete?

Expected Vitals for Newborn Foals

| AGE (hours) | HEART RATE (/min) | RESPIRATORY RATE (/min) | TEMPERATURE (°F) |

| 0-2 | 120-150 | 60-80 | 99-100.5 |

| 2-36 | 90-120 | 20-40 | 99-101.5 |

| 48+ | 60-80 | 20-40 | 99-101.5 |

Other Things People May Do to Neonatal Foals Prophylactically

- Prophylactic antibiotics

- On farms that have particular problems with septicemia or other neonatal bacterial infections, foals may be placed on antibiotics for the first 3-5 days of life. There is evidence in some studies of a significant reduction in serious infections when this is done.

- Hyperimmune plasma

- Plasma from donor animals specifically vaccinated to provide high antibody titers against certain diseases is commercially available (e.g. against clostridial organisms) and is used as an IV infusion, usually in the first day of life, on farms that have particular problems.

- Some may also be administered by stomach tube to provide high levels in the gastrointestinal tract to prevent toxin absorption or bacterial adhesion (depending on whether you give an antitoxin-based antibody or one against the bacteria itself)

- Blood sample for complete blood count (CBC)/chemistry

- People who have had sick foals previously may have a blood sample submitted for a CBC and serum chemistry panel as another early indicator of any possible infection (the earlier you can detect and treat the better it usually goes).

- If the foal is being insured, a CBC may be part of the insurance company requirement prior to issuing a policy.

Physical Exercise for Newborn Foals

Foals have a fairly large surface area to volume ratio and not much in the way of insulating adipose tissue, so they depend on food intake and movement to generate heat. Provided the foal is normal and the weather and footing reasonable they can start life outside right away; obviously, that is the way they were designed. However, since we often modify the breeding season for economic reasons so birth is close to January 1st, conditions are often less than ideal. In particularly cold weather the mare and foal are usually housed inside, ideally with turnout a couple of times a day in an indoor arena or at least hand walking.

Foals with abnormalities of the musculoskeletal system (identified by management or on the veterinary examination) are more restricted:

- Premature and dysmature foals with incompletely ossified cuboidal bones are kept in a stall and often non-weight-bearing (i.e. lying down) as much as possible to avoid crush injury until ossification is complete (monitored by serial radiographs).

- Foals with tendon laxity are given controlled exercise, usually turnout in a small area so they don’t try to get up too much speed until the tendons strengthen.

- Foals with tendon contracture have fairly heavy bandages or even casts put on their legs which actually encourage tendons to relax (you restrict something on a foal and it tends to respond by getting floppy), with some very controlled exercise to encourage stretching, and pain control (e.g. a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory like ketoprofen).

Other treatments for these can include frequent foot trims, corrective shoeing (glue on at this age), and medical and surgical options for those that are more severe or are not responding to conservative management.

*

Care of Calves

Care of Calves

Disease in dairy calves is not uncommon, with incidence of pre-weaning mortality reported as 5.6% and incidence of post-weaning mortality reported as 1.9%. Common causes for pre-weaning mortality include scours (gastrointestinal disease), respiratory disorders, and calving problems. The most common cause of post-weaning mortality is respiratory disease.

Calfhood disease is associated with short-term losses (labor to manage calves, drugs, calf mortality) and long-term losses (decreased rate of gain, increased risk of death before achieving goals as an adult such as increased risk of culling before first calving or increased age at first calving). Specific goals are set by the Dairy Calf and Heifer Association; these standards give farmers and their veterinarians goals to shoot for in disease management. For example, the goal for a given farm for pre-weaning mortality is less than 3%.

Key Management Areas for Pre-Weaned Dairy and Beef Calves and Specific Management Strategies

Late Gestation

In the last trimester, nutrition, immunity, and environment/housing of cows must be managed. Be aware that dairy cows are bred and calve year-round and that beef cows are bred and calve seasonally, with calving seasons in spring and fall. Late gestation nutrition includes feeding a diet balanced for energy, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Food must be palatable and may be available free choice. Free choice fresh water must be available. Body condition score should be at or just above average (3.0 to 3.5 on a 5-point scale for dairy cows, 5 to 6 on a 10-point scale for beef cows). Poor nutrition is associated with lower birth weight of calves; difficulty calving, especially in fat cows; lower production of colostrum and milk; slower calf growth; and overall lower calf survival. Cows are often vaccinated late in gestation to ensure high antibody concentrations in colostrum to protect the calf. In the time just prior to calving, dairy cows should be housed on clean, dry bedding and should not be overcrowded. Control heat in the summer (shade, fans, sprinklers) and provide protection from wind and precipitation in the winter. Beef cows are tough but do require a wind break, access to bedding, and access to feed.

Calving Environment

The calving area must be well-bedded and draft-free. It is important to keep it as clean and dry as possible by frequently removing dirty bedding and adding clean bedding. The calving area must be well away from pens for sick animals in the facility. Animals should be handled in a calm manner. Try to keep the cow from standing in mud, which is made up of manure, urine, and dirt. Her udder and the ground will be the first things to which the calf is exposed and both should be as clean as possible. An example of a pasture rotation system used in beef cattle to ensure calves are born on clean, parasite-free pasture is the Sandhills Calving System – The Sandhills Calving System uses larger, contiguous, pastures for calving, rather than high animal-density calving lots. Cows are turned into the first calving pasture (Pasture 1) as soon as the first calves are born. Calving continues in Pasture 1 for two weeks. After two weeks the cows that have not yet calved are moved to Pasture 2. Existing cow-calf pairs remain in Pasture 1. After a week of calving in Pasture 2, cows that have not calved are moved to Pasture 3 and cow-calf pairs born in Pasture 2 remain in Pasture 2. Each subsequent week cows that have not yet calved are moved to a new pasture and pairs remain in their pasture of birth. The result is cow-calf pairs distributed over multiple pastures; each containing calves within one week of age of each other. Cow-calf pairs from different pastures may be comingled after the youngest calf is four weeks of age and all calves are considered low-risk for neonatal diarrhea.

Care of the Newborn Calf

For beef calves, calving should be monitored and assisted if needed. The calf’s umbilicus should be disinfected with 7% tincture of iodine. The calf is assessed to ensure good vigor and a protected area with or without a heat lamp and other supportive care is provided if needed. The calf is individually identified with an ear tag and will remain with the cow until weaning. For dairy calves, calving should be monitored and assisted if needed. The calf’s umbilicus is disinfected with 7% tincture of iodine. The calf is immediately removed from the cow (within 30-60 minutes of birth) and is raised separately from her. Immediately post-partum, the calf is dried in a warming box, with a heat lamp, or in a warm room if the calf is born during cold winter months. Calf blankets may be used and the calf is individually identified with an ear tag.

Colostrum

Cows have an epithelichorial placenta with six complete layers (three each from the fetus and dam). There is virtually no movement of antibodies across this placenta so all calves are born without protective circulating antibodies. Colostrum, the first milk secreted after parturition, is rich in immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM), cytokines, and nutrients. Colostral antibodies are absorbed across the gut early in the calf’s life and so help the calf develop circulating concentrations of antibodies that provide temporary immune protection until the calf’s immune system develops. Blood can be drawn from calves between 24 hours and 7 days of age to determine if they have had sufficient antibody transfer; normal values are greater than 10 mg/mL of serum IgG and/or greater than 5.2 gm/dL of serum total protein. Dairy calves are presented with colostrum by the farmer in the first days of life. Beef calves get colostrum directly from the dam; if the cow is not a good mother or the calf if not nursing for some other reason, the calf may need to be fostered onto another cow or handfed to ensure it receives colostrum. It is reported that up to 14% of dairy calves in the United States have insufficient transfer of antibodies (“failure of passive transfer”) and that 31% of deaths in the first 3 weeks of life are associated with failure of passive transfer.

Specifics of colostrum management include:

- Evaluation of quality – The goal is to have greater than 50 gm/L of IgG in colostrum. Factors that impact colostrum quality include late gestation (dry cow) vaccinations, dry cow nutrition, avoiding stress in dry cows (heat, crowding), and ensuring the dry period is of adequate length (not shorter than 21 days). Antibody concentration is measured on a colostrometer or Brix (sugar) refractometer (22% total solids = 50 gm/L IgG).

- Ensure calves are receiving the right quantity – The goal is to feed 150-200 gm of IgG. This usually is done by providing 10% of the calf’s body weight (usually 3-4 liters or 4 quarts) within 6 hours of birth. Dairy calves can be fed using a nippled bottle or an esophageal tube feeder.

- Ensure time to first feeding is as quick as possible – The gut loses ability to absorb large proteins like antibodies by 24 hours of life so the goal is to provide colostrum orally within the first 1-2 hours of life if possible.

Beef calves are left to nurse off of the cow and to receive colostrum with less oversight. Someone should verify that the cow has colostrum (thicker and yellower than regular milk), that the cow’s teats are patent, that the calf is up and trying to nurse, and that the dam is allowing the calf to nurse. If a dairy or beef cow has no colostrum, calves can be fed frozen colostrum from storage, or colostrum replacement products. As in foals, blood can be drawn from calves within the first week of life to determine if they have received adequate colostrum.

Pre-Weaning Nutrition

See Nutrition-Herbivores chapter.

Housing and Sanitation

The goal when housing dairy calves prior to weaning is to avoid contact of that calf with older animals or their environment, including air, water, bedding, feed, and pasture used by older animals. Calves also should not directly contact each other. The housing may be individual calf hutches or other individual enclosures. If producers do group dairy calves prior to weaning, then introduction to the group should be delayed until the calf is 12-14 days old, and group sizes should be kept as small as possible (< 8 calves/group) in order to reduce disease risk. The enclosure should be draft-free but well ventilated and bedded with abundant clean, dry bedding. Enclosures should be well cleaned and sanitized between uses. The setup should be such that calves can be managed and moved with minimal stress and decreased risk of injury. Calves are not in solitary confinement when in calf hutches; a study published in Applied Animal Behavior Science in 2015 demonstrated that calves that had gentle interactions with handlers up to three minutes per day as they received their normal feeding and care gained more weight in the first two weeks of life.

Research has shown some benefits of allowing pre-weaned calves to socialize (i.e. have a buddy). Pair housing (groups of 2 calves) is a viable compromise to allow socialization between pre-weaned calves while still minimizing the increased disease risk that occurs if we group pre-weaned calves. Since early weight gain is associated with increased milk production as an adult, this has behavioral benefits for the calves and benefits for the producer as well.

Health Procedures

Which procedures are performed depends on the farm, with the program determined by the farmer and veterinarian. Examples include ear tag application and dipping the umbilicus as described above, testing serum protein concentrations to assess for failure of passive transfer, tests for specific diseases, vaccination, dehorning, and castration.

Disease Detection and Treatment

This again varies by farm. Early detection and treatment of disease improves success and may help prevent spread of disease in the facility. Veterinarians may be involved in helping develop protocols and in training farm staff.

*

Care of Piglets

Care of Piglets

The following notes are largely excerpted from: http://extension.missouri.edu/p/G2500

The most critical period in the life cycle of a pig is from birth to weaning. On the average, about 1-2 piglets per litter are lost during this period, with an average pre-weaning mortality of 12%. As number of piglets per litter increases, birth weights of individual piglets decreases. Piglets that weigh less than 2.2-2.4 pounds (1 kg) at birth have more than a 50% chance of dying before weaning. Other common causes of mortality are crushing, starvation, and dehydration due to diarrhea.

Weaning large litters of thrifty, heavyweight pigs is a key factor for a profitable swine herd. This publication attempts to outline management practices that help keep pigs alive and profits high.

Farrowing

Preparation for Farrowing

The average gestation period for sows is 114 days. To prepare for farrowing, producers should know when sows are due. Producers should be ready for delivery prior to the due date because of individual variation in gestation.

Newborn piglets have a better survival chance if they arrive in a clean, warm, and sanitized farrowing facility. Research has shown that a break between farrowing reduces disease buildup. Many producers, however, only allow for a one-day break between groups of sows to maximize use of expensive facilities. If the facility is used continuously, cleaning and sanitation must be optimized to control spread of disease.

In addition, it would be beneficial to wash the sow with soap and warm water immediately prior to being put into the farrowing stall; this is rarely done for practical reasons.

Care at Farrowing

Three basic requirements for newborn pigs:

- A good environment

- Adequate and regular nutrition

- Safety from disease and crushing

Individual attention from the producer at this point pays off with more live pigs. The amount of labor available may determine how much time you spend in the farrowing house. One dedicated team in charge of the farrowing works well in larger operations. The table below indicates the scope and causes of piglet mortality.

*

Causes of piglet death (Leman and Knudson, 1972)

| CAUSE | PERCENTAGE AFFECTED |

| Crushing | 30.9 |

| Starvation | 17.6 |

| Born Weak | 14.7 |

| Chilling | 5.5 |

| Transmissible gastroenteritis | 3.9 |

| Other diarrheas | 12.9 |

| Pneumonia | 1.4 |

| Others | 13.1 |

| TOTAL | 100 |

Management — First Few Days After Farrowing

There are many essential chores to be done shortly after pigs are born. The navel should be disinfected the day pigs are born using tincture of iodine. If possible, match the number of piglets to the number of functional mammary glands. If several sows are farrowing within a 24-hour period, pigs can be transferred successfully from one sow to another if piglets are moved within the first 3 days of life and have received colostrum before transfer. Transfer bigger pigs in the litter, not the runts. Transfer of piglets may not be recommended during a disease outbreak; for example, pork producers were working through emergence of the new disease Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea (PED) in 2013 and veterinarians were recommending not moving piglets as a biocontainment measure.

Clip needle teeth, being careful not to crush the teeth or cut the gums. “Pigs are born with eight needle (sometimes called wolf) teeth located on the sides of the upper and lower jaws. Historically, needle teeth were clipped in newborn pigs to prevent potential damage to the sow underline and consequentially, a reluctance to allow nursing. Clipping needle teeth was also seen as a means for preventing injuries to the faces of littermates when fighting occurred. Some producers have totally abandoned the procedure or clip needle teeth only when sows are not milking well or if disease is present in the herd. [Based on a study performed at Virginia Tech], they suggest that “clipping needle teeth may be warranted on some farms to prevent pig and teat injuries, and that the process has no positive or negative impact on pig and sow performance.” (Excerpt from Virginia Tech Extension) A controlled study comparing litters with clipped or intact needle teeth showed no difference in weight gain and mortality but demonstrated that piglets with intact needle teeth were more likely to have facial injuries. One of the students in the class of 2019 shared that she worked at a farrowing unit where they chose to stop clipping needle teeth for a time. They decided to start clipping needle teeth again because they found that when they were clipped, the piglets had fewer facial swellings and infections from biting each other and the sows were more comfortable and less likely to jump up and interrupt nursing of piglets because their underlines were not being traumatized by the needle teeth when piglets were suckling.

At the same time needle teeth are clipped, tails can be docked. Tail docking is performed to prevent tail biting and cannibalism among pigs later in life. Leave a stub on the tail about 1/4-inch long. Tail-docking is best done when the pigs are one day old. Ear-notching is practiced in some smaller herds. This identification helps select replacement animals from top litters and gives a check on age when pigs reach market weight. An evaluation of welfare implications of teeth clipping, tail docking, and permanent identification of piglets is available from the AVMA.

Iron deficiency develops rapidly in nursing pigs reared in confinement because of:

- Low body storage of iron in the newborn pig

- Low iron content of sow’s colostrum and milk

- Elimination of contact with iron from soil

- The rapid growth of the nursing pig

Iron deficiency is associated with inability to produce hemoglobin and subsequent anemia. There are many good sources of iron that can be used to prevent anemia. Iron-dextran injected in the muscle is an effective method. Injections are done in the neck. Common levels are 150-200 milligrams of iron as iron-dextran, usually given the first 2 days after birth. Don’t give overdoses of iron because it may induce shock. Iron also can be mixed in the feed or in the drinking water. Supplying uncontaminated soil in the pig area is another method of supplying iron but is not used much in today’s confinement systems.

Management During Lactation

Baby Pig Scours

Baby pig scours are major ongoing problems for swine producers. Most common diarrheas are caused by various strains of E. coli. The symptom of E. coli-induced diarrhea is a watery, yellowish stool. Pigs are most susceptible from 1-4 days of age, at 3 weeks of age, and at around the time of weaning. Although pigs are born with little disease resistance, this resistance increases as they absorb antibodies from their mother’s colostrum. Because pigs’ ability to absorb antibodies decreases rapidly from birth, it becomes important that they feed on colostrum soon after birth. Colostrum provides the only natural disease protection they will have until their own mechanism for antibody production begins to function effectively at 4-5 weeks. Disease resistance is lowest at 3 weeks. It is wise to avoid unnecessary stress (castration, vaccination, worming) at this time. In treating common scours, orally administered drugs are usually more effective than injections. You should use a drug effective against the bacterial strain on your farm. It is important to remember that many viruses also can be the cause of baby pig scours. A dry, warm, draft-free environment is of primary importance in reducing scours. Sanitation is also very important in reducing the incidence of baby pig scours.

Castration

Boar pigs can be castrated any time before they are 4 weeks old. In most states, it is legal for the farmer to perform this surgery in pigs and it is done before the piglets are one week old.

*

Extra Resources

Extra Resources

- Clipping of needle teeth: http://www.sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/livestock/aps-01_11/aps-0431.html

- Valgus and varus: www.acvs.org/large-animal/angular-limb-deviation

- Pediatric course information from Dr. Peggy Root: https://sites.google.com/a/umn.edu/margaret-v-peggy-root-kustritz/home/archived-courses/cvm-6451—pediatrics