Nervous system: Drugs and Addiction

Learning Objectives

Know what a drug of abuse is and what it does in the brain. Understand how the brain’s response to drugs changes over time and how this contributes to addiction

As you’ve grown up, you’ve probably been bombarded with the simple message “DON’T DO DRUGS” from family, teachers, and advertisements. But why is this such an important message that it bears repeating over and over and over again? What are drugs actually doing in our brains that make the adults in your life so worried about you trying them?

When we talk about not “doing drugs,” we are talking about recreational use of a drug, or using a drug “just for fun,” which is considered abusing that drug, and can lead to becoming addicted to it. This is why we call them “drugs of abuse.” This group of drugs includes players such as: heroin, alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine, nicotine (aka cigarettes/e-cigarettes), and marijuana. This does not include properly-taken medications, even though some medications are also drugs of abuse when taken improperly, like how morphine (which is related to heroin and can be addictive) is used for pain-relief, or how microdosing of ketamine (aka horse tranquilizer) is being tested as a treatment for depression.

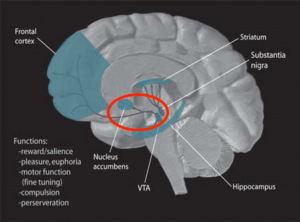

The way drugs of abuse work in the brain is by targeting, either directly or indirectly, an area of the brain called the mesolimbic dopamine system. This pathway includes the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA), which sends dopamine signals to the Nucleus Accumbens. Dopamine is one of the major neurotransmitters–or chemical signals–in the brain that relays information on whether something is rewarding or exciting. When it comes to addiction, dopamine is the little voice in your head saying “that felt good, do that again.” This is why the mesolimbic dopamine pathway is often lovingly referred to as simply: The Reward Pathway. Almost all drugs of abuse go through this pathway in some way to increase the amount of dopamine in the brain to make someone feel good and make them want to take a drug again.

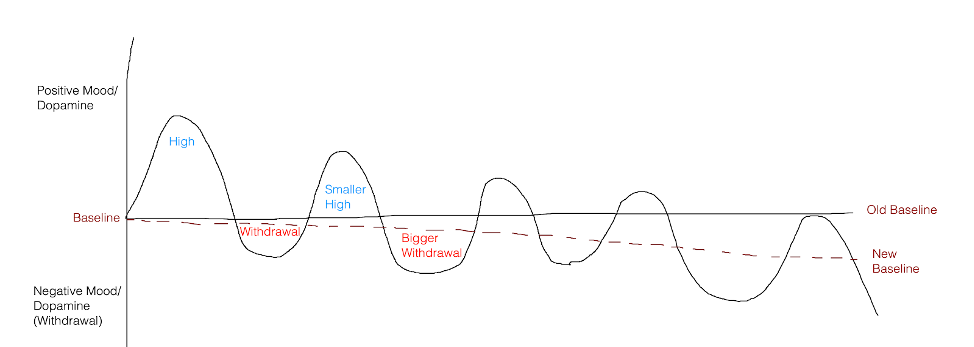

You might see how this itself could cause addiction, or a physical and/or psychological NEED for a drug. If a drug feels that good, it would make sense to keep using it to keep feeling good and chasing that high. That is definitely part of addiction. But wait, there’s more! We all have a baseline level of dopamine that our body likes to stay at. When we take a drug, that level increases. When a drug leaves the system, dopamine levels drop below baseline levels, throwing a person into what is called withdrawal, which includes symptoms such as anxiety, depression, physical ailments (stomach issues, pain, etc.), and craving that drug to get back to feeling good. As time goes on and a person goes back to using a drug over and over again (maybe to feel good, maybe to run away from withdrawal), the highs get smaller and the lows get bigger, and while that is happening, the baseline level of dopamine is also lowering itself. This physical change can stick around long-term, which is why addiction is considered a chronic disorder and why even years after stopping a drug some people still feel cravings for that drug.

Drugs which are commonly misused either illegally, without a prescription, or in over abundance.

Using a very small dosage to treat someone

An area of the brain focused on motivated/rewarding actions such as eating. This area is responsible for making an organism want to repeat an action which promotes survival. Drug hijack this system, causing addiction.

A part of the mesolimbic dopamine system which tells the brain something is rewarding or exciting.

This is the part of the mesolimbic dopamine system which reinforces rewarding actions.

chemical messengers which allow brain cells to communicate with each other.

The symptoms associated with the absence of a substance which a person is dependent on.