Part 5: Porcine Abdominal Viscera

Abby Brown

Self-Study of Porcine Abdominal Viscera

Porcine Viscera (DRY & wet, if available):

- Study the available porcine (pig) viscera. On a fresh specimen, the first thing you may notice is that the large intestines are green colored in contrast to the off-white colored small intestine. The green coloration is not present in life but occurs shortly after death.

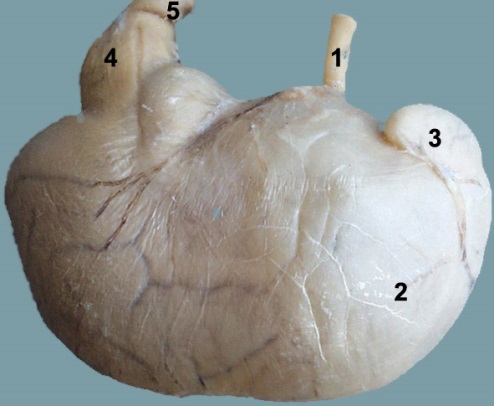

- Observe the liver (TVA 769) to identify its lobes, which have a pattern similar to that of the dog. On the visceral surface, between the quadrate and right medial lobes of the liver, identify the gallbladder.

-

- As mentioned, the lobes of the liver in the pig are similar to that of the dog; there is a left medial and a left lateral lobe, a small quadrate lobe, a right medial, a right lateral and a caudate lobe.

- Find the esophagus and trace it to the stomach. Note the elongated spleen which is loosely attached to the greater curvature of the stomach by the greater omentum.

- In situ, the spleen may be so elongated that the ventral tip will cross the midline to the right side.

- If not already done for you, open the stomach along the greater curvature and locate the cardiac region which is surrounded by stratified squamous epithelia continuous with the lining of the esophagus. This tough white mucosa is the non-glandular region which is smaller than the glistening dark red glandular region.

- Comparative Note: Note that these two regions (glandular and non-glandular) are poorly separated in the pig, whereas they were well separated in the horse.

- On the dorsal extremity of the stomach note a separate small compartment; this is the gastric diverticulum (Figure 5-20, and TVA 767, left, 2).

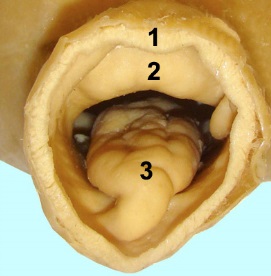

- Extend the incision in the stomach along the greater curvature to the pylorus/pyloric region and observe the thick pyloric sphincter muscle and the bulb-like torus pyloricus (Figure 5-21).

- Note that the torus pyloricus is found in ruminants and pigs and may act as a valve to seal, or limit, outflow from the stomach.

- Trace the relatively straight duodenum from the stomach to the more convoluted jejunum.

- Locate the straightened ileum as it enters the colon. Note that there is an ileocecal fold found between the ileum and cecum. Identify the cecum.

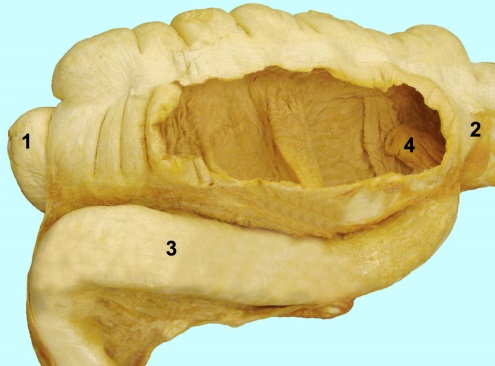

- If not already done for you, open the cecum and initial part of the colon with a longitudinal incision to observe a very distinct raised ileal papilla on which the ileal orifice opens (Figure 5-22).

-

- Comparative Note: Among the domestic animals, an ileal papilla is well-developed only in swine; it marks the initial part of the colon.

- If needed, wash out the contents of the cecum and the first part of the colon to observe the ileal papilla.

-

- If not already done for you, open the cecum and initial part of the colon with a longitudinal incision to observe a very distinct raised ileal papilla on which the ileal orifice opens (Figure 5-22).

- In the pig, the cecum and ascending colon (aka spiral colon) form a cone-shaped mass that is bound together by mesentery (see Figure 5-16). Identify the parts of the colon as described below.

-

The first part of the ascending colon, the centripetal (center seeking) loop, spirals toward the central flexure and surrounds the smaller diameter centrifugal (center fleeing) loop that spirals away from the central flexure.

-

The cecum and centripetal loop are marked by two longitudinal smooth muscle bands that pull the wall into pleats known as sacculations.

-

Comparative Note: Of the domestic animals, bands and sacculations are only seen in the pig, horse, and rabbit, but they are also found in the human large intestine.

-

- After the spiral colon, identify the transverse and descending (small) colon.

-

- Note that there are also dry museum specimens that demonstrate some of the very distinctive structures in the pig. You should be able to identify the relevant structures on each of those specimens, as they are fair game on assessments. (Figs. 5-20, 5-21, & 5-22)

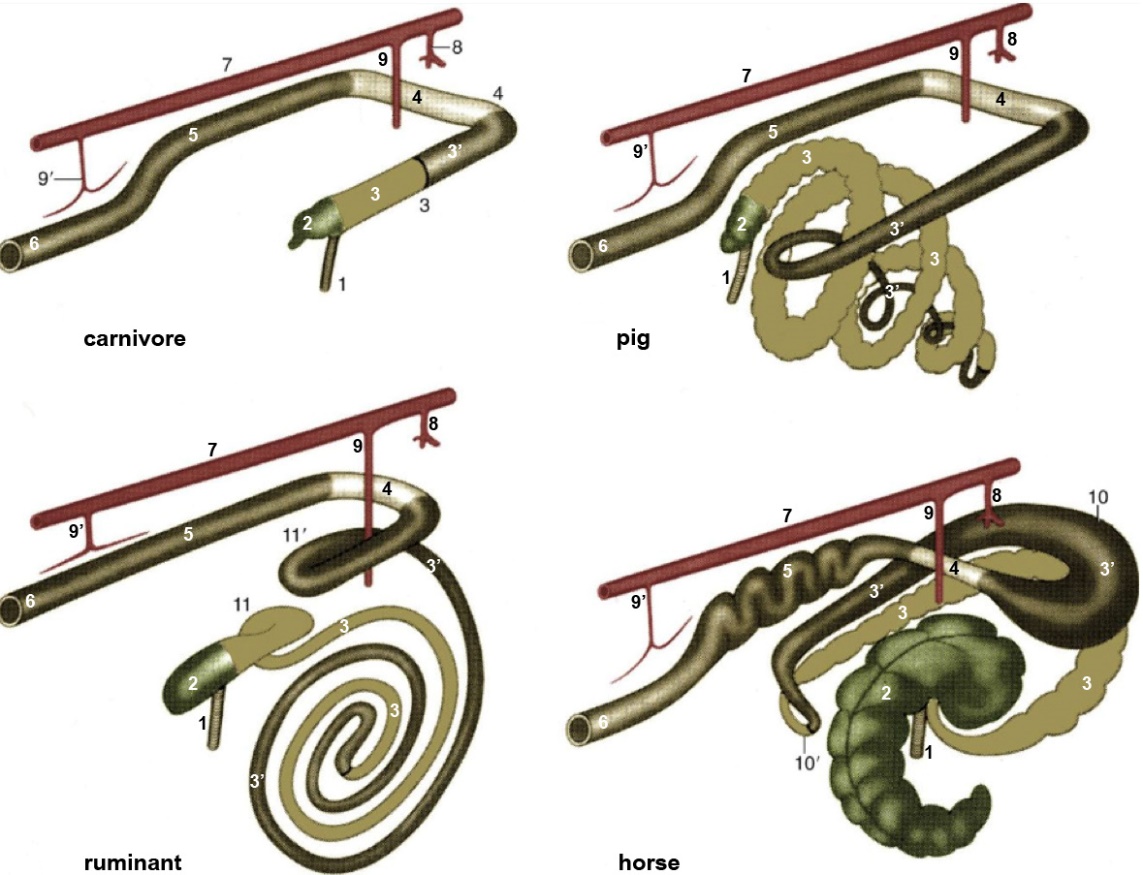

(Duplicate) Figure 5-16. Schematic drawing of the large intestine of the domestic mammals. The cranial aspect is to the upper right of each image. 1, ileum; 2, cecum; 3, 3’ ascending colon; 4, transverse colon; 5, descending colon; 6, rectum and anus; 7, aorta; 8, celiac artery; 9, 9’, cranial and caudal mesenteric arteries; 10, 10’, dorsal diaphragmatic and pelvic flexures of ascending colon; 11, 11’, proximal and distal loops of ascending colon. (TVA Fig. 3-45)

(Duplicate) Figure 5-16. Schematic drawing of the large intestine of the domestic mammals. The cranial aspect is to the upper right of each image. 1, ileum; 2, cecum; 3, 3’ ascending colon; 4, transverse colon; 5, descending colon; 6, rectum and anus; 7, aorta; 8, celiac artery; 9, 9’, cranial and caudal mesenteric arteries; 10, 10’, dorsal diaphragmatic and pelvic flexures of ascending colon; 11, 11’, proximal and distal loops of ascending colon. (TVA Fig. 3-45)

Figure 5-20. (Left) Pig stomach. 1, esophagus; 2, fundus; 3, gastric diverticulum; 4, pyloric region;5, duodenum

Figure 5-21. (Left) Pyloric region of pig stomach (enlarged).1, cut edge of duodenum just distal to the pyloric sphincter (2); 3, torus pyloricus

Figure 5-21. (Left) Pyloric region of pig stomach (enlarged).1, cut edge of duodenum just distal to the pyloric sphincter (2); 3, torus pyloricus

Figure 5-22. Dry pig cecum with a window cut to expose the ileal papilla (4). 1, apex of cecum; 2, initial part of colon; 3, ileum; 4, ileal papilla. (The ileal papilla opens into the colon and marks the initial part of the colon.)

Dissection Videos for this Section of Material

Porcine