Basics: neuroscience and psychophysics

6 Action Potentials

Learning Objectives

Distinguish between action potentials and graded potentials

Understand that action potentials are all-or-nothing events—size doesn’t matter, rate does

Understand that both the rate and timing of action potentials have a random component

The Membrane Potential

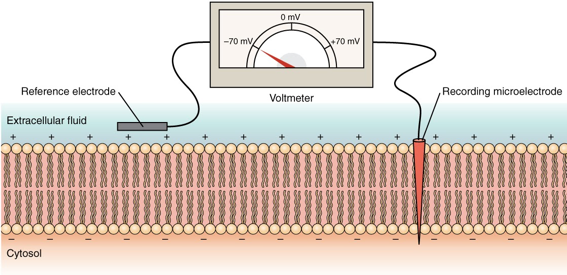

The electrical state of the cell membrane can have several variations. These are all variations in the membrane potential. A potential is a distribution of charge across the cell membrane, measured in millivolts (mV). The standard is to compare the inside of the cell relative to the outside, so the membrane potential is a value representing the charge on the intracellular side of the membrane based on the outside being zero, relatively speaking.

Action Potentials vs. Graded Potentials

Resting membrane potential describes the steady-state of the cell, which is a dynamic process that is balanced by ion leakage and ion pumping. Without any outside influence, it will not change. To get an electrical signal started, the membrane potential has to change.

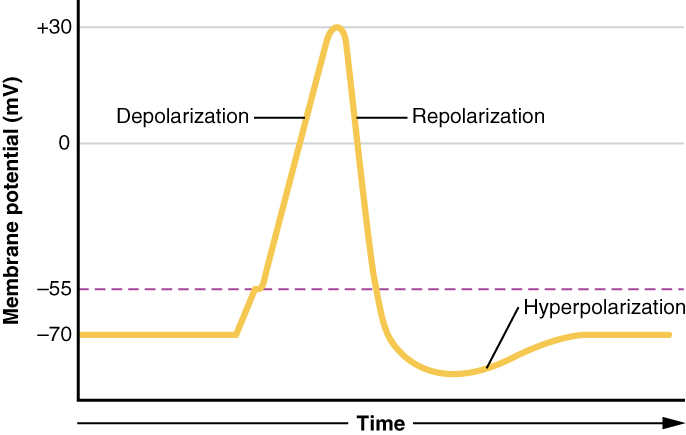

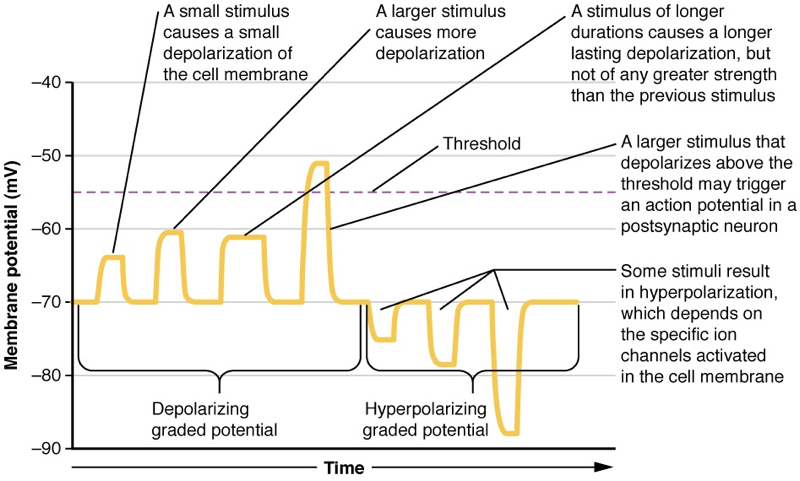

Each neuron, and each section of each neuron, has a specific distribution of ion channels in the cell membrane that determines how the membrane potential can change. Axons have the right distributions and types of Na+ and K+ channels to support action potentials, which are all-or-nothing events (Figure 6.2). In dendrites, on the other hand, and in specialized sensory neurons like the photoreceptors in the retina, graded potentials happen instead of action potentials (Figure 6.3). Unlike action potentials, graded potentials can be different sizes and can be positive or negative. Therefore, graded potentials are analog signals while action potentials are digital signals.

For the unipolar cells of sensory neurons—both those with free nerve endings and those within encapsulations—graded potentials develop in the dendrites that influence the generation of an action potential in the axon of the same cell. This is called a generator potential. For other sensory receptor cells, such as taste cells or photoreceptors of the retina, graded potentials in their membranes result in the release of neurotransmitters at synapses with sensory neurons. This is called a receptor potential.

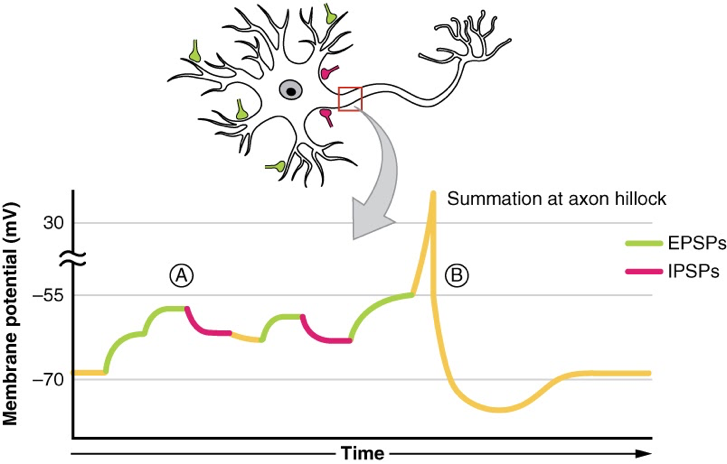

A postsynaptic potential (PSP) is the graded potential in the dendrites of a neuron that is receiving synapses from other cells. Postsynaptic potentials can be depolarizing or hyperpolarizing. Depolarization in a postsynaptic potential is called an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move toward threshold. Hyperpolarization in a postsynaptic potential is an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) because it causes the membrane potential to move away from threshold.

Variability in Action Potential Rates and Times

Given the complex mechanisms that generate action potentials, it is no wonder that there is a bit of randomness in the process. A sensory neuron will not respond in the exact same way every time a stimulus is present. On average, a more intense stimulus will result in stronger graded potentials and, after summation, a higher rate of action potentials. But on each trial (each time the stimulus is applied), the rate will not be exactly the same, and the timing of all the spikes in the spike train will not be the same. Sometimes, there are systematic differences. For example, neurons adapt to stimuli, and respond more weakly after repeated trials. On top of this, there are also random differences. In order to support perception, neural networks must evolve efficient strategies for making perceptual decisions even in the presence of sensory noise.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Anatomy and Physiology Section 12.4 Action Potential

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

License: CC-BY 4.0

OpenStax, Anatomy and Physiology Section 12.5 Communication Between Neurons

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

License: CC-BY 4.0

References:

Byrne, J. H. (2023). Neuroscience Online: An Electronic Textbook for the Neurosciences [Webpage]. McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. Retrieved from https://nba.uth.tmc.edu/neuroscience/m/s1/chapter01.html#s1.2

Michigan State University. (2022). Introduction to Neuroscience: Molecular Mechanisms of Memory: Aplysia. Retrieved from https://openbooks.lib.msu.edu/introneuroscience1/chapter/molecular-mechanisms-of-memory-aplysia

Zedalis, J., & Eggebrecht, J. (2018). Biology for AP® Courses. Houston, Texas: OpenStax. Retrieved from https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/26-2-how-neurons-communicate