Light and Eyeballs

86 Light Transduction and Dark Adaptation

Learning Objectives

Know what the role of the pigment epithelium is in the light transduction process.

Be able to describe the different stages of dark adaptation (time duration, luminance levels, etc.).

Know the differences between our scotopic and photopic vision.

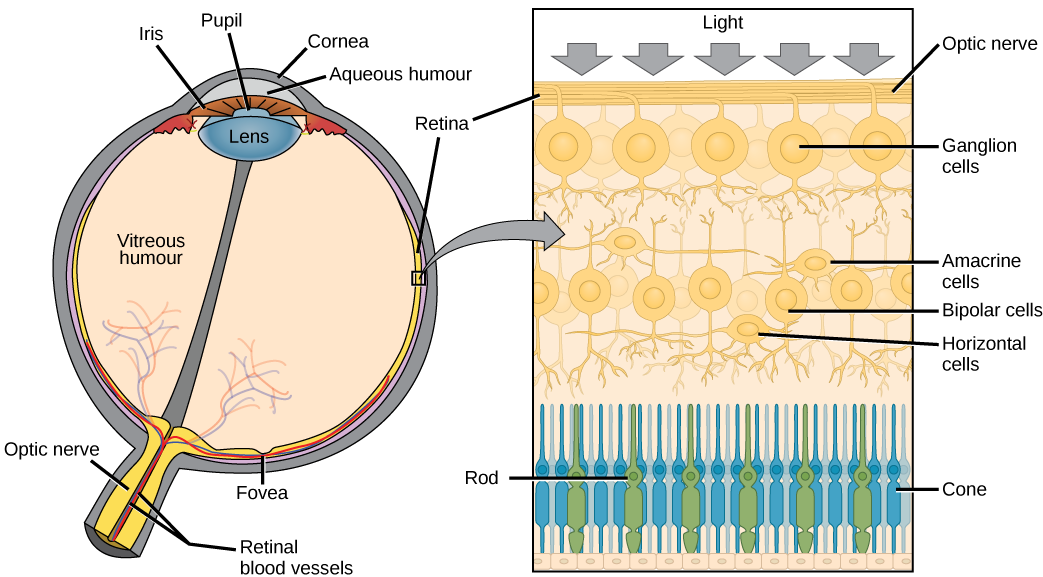

How do we experience light? When light reaches the back of the eye, it enters the retina. The retina is composed of many layers and contains specialized cells known as photoreceptors. There are two types of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are sensitive to vision in low light, whereas cones are sensitive to brighter light and — because there are 3 different kinds of cones — allow us to perceive color in normal lighting.

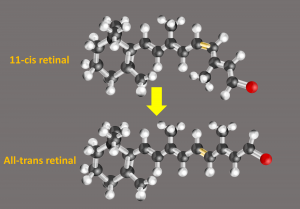

Light transduction happens in the outer segments of the rods and cones. This means that light travels through several layers (ganglion cells, bipolar and amacrine cells) before it does anything! Light falling on the retina causes chemical changes to pigment molecules in the photoreceptors, ultimately leading to a change in the activity of the rods and cones. When light (of the right wavelength/color) hits 11-cis retinal, it changes conformation (to all-trans), acting as a switch to start an enzyme cascade in the cell, which eventually changes the rate at which photoreceptors release neurotransmitters.

After absorbing light, all-trans retinal needs to be turned back into 11-cis retinal. So it breaks off its opsin, finds its way to the pigment epithelium, gets bent back into shape, and finds its way back to an opsin. This is why photoreceptor outer segments need to be close to the pigment epithelium, which is the back layer behind the retina where visual pigments are replenished.

Dark adaptation refers to the ability of both rod (scotopic) and cone (photopic) mechanisms to recover sensitivity in the dark following exposure to bright lights. The first rapid recovery is attributed to the cones and the later recovery to the rods. Let’s break it down into a timeline

- First Few Minutes: The rods and cones both become more sensitive during the first few minutes. However, after 5-10 minutes, the cones reach their maximum sensitivity. This is known as the rod-cone break because it’s the point where rods become more sensitive than cones.

- 5-10 Minutes: The rods will continue to become more sensitive over the next few hours as they regenerate a receptor protein called rhodopsin. After 7 or 8 minutes, the rod photopigments have replenished enough that the rods become the most sensitive cells in the retina, and sensitivity continues to improve for another 13-22 minutes (20-30 total) while the rod visual pigment finishes replenishing.

- 30 Minutes: At this point, the rhodopsin has mostly been replenished, so you should be about 90% dark-adapted.

Rhodopsin, the photopigment on rods, plays a large role in dark adaptation because it’s so sensitive. Light causes it to deteriorate rapidly, in a process called photobleaching. Photobleaching occurs when the pigment epithelium cannot regenerate 11-cis retinal as fast as it is converted to all-trans retinal. During daylight viewing, rods are essentially completely photobleached, and cones are partially photobleached.

So if you’re trying to get dark-adapted, it’s crucial to avoid light—it can undo hours of dark adaptation in seconds. All the rhodopsin you have built up over the previous 30+ minutes disappears, and it will take time for your retina to replenish it.

OpenStax, Anatomy and Physiology Chapter 14.1 Sensory Perception

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/14-1-sensory-perception

License: CC-BY 4.0Cheryl Olman PSY 3031 Detailed Outline

Provided by: University of Minnesota

Download for free at http://vision.psych.umn.edu/users/caolman/courses/PSY3031/

License of original source: CC Attribution 4.0

Adapted by: Faith Sanchez

Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System, Light and Dark Adaption by Michael Kalloniatis and Charles Luuz

URL: https://webvision.med.utah.edu/book/part-viii-psychophysics-of-vision/light-and-dark-adaptation/

License: CC BY-NC

Adapted by: Savannah Whisenhunt