Taste and Smell

33 Experiencing Scent

Learning Objectives

Be able to describe the paradoxical relationship between scent and memory.

Know the distinction between detection and recognition of a scent.

Know whether or not it is a myth that females have a better sense of smell than males.

The strong projections from the olfactory tract to piriform cortex and other regions associated with memory (e.g., parahippocampal gyrus) and emotion (e.g., the amygdala) help us understand why smells readily evoke memories, and why the emotional content of smell-evoked memories is often stronger than other memories (Willander, 2007). However, the relationship is one-directional. While smells evoke memories, we’re not always good at recognizing scents.

When studying scent detection, there are two types of thresholds that are used to measure this: Recognition thresholds and absolute/detection thresholds. Recognition thresholds are the shortest exposure to a stimulus at which recognition of that stimulus can occur. They measure the lowest rate at which a smell can be recognized, simply it asks the question “what are you smelling?” Absolute/detection threshold on the other hand is the lowest or weakest level of stimulation that can be detected on 50% of trials. They measure the lowest rate at which a smell can even be detected, rather than what that specific scent is, simply, they ask the question “what are you smelling?”

Olfactory anatomy is the same for both sexes, but there is some experimental evidence that females perform slightly better at standardized smell tests than males (Sorokowski, 2019). Differences in performance are likely related to experience (some bias might occur in testing if one sex is more likely to have experience with test scents than others) and possibly sex hormones.

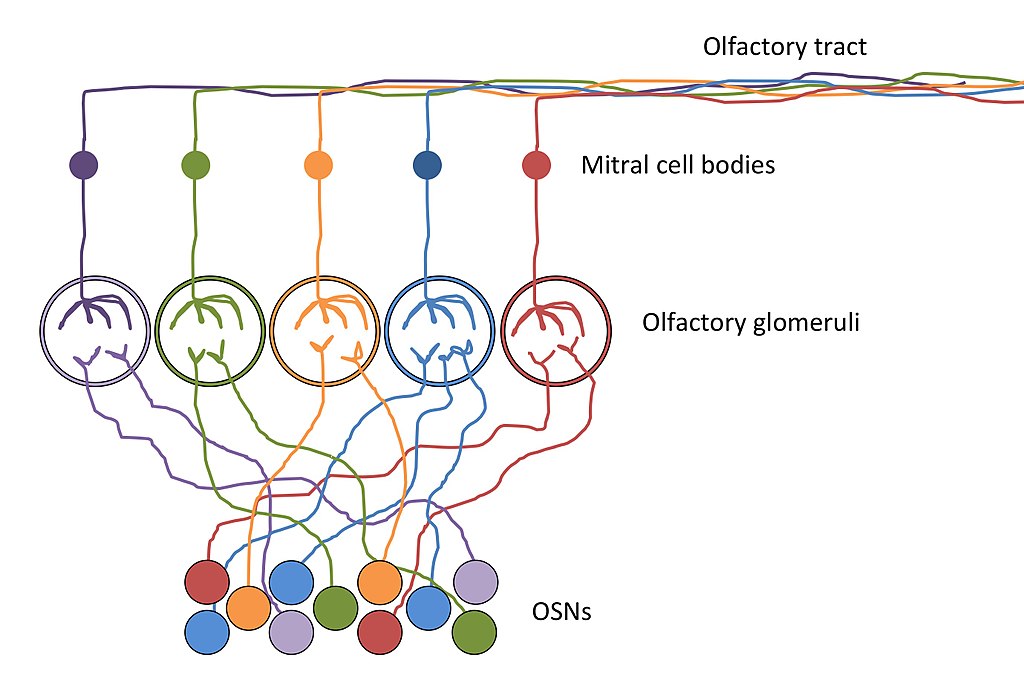

Predicting how something is going to smell to someone is difficult—each molecule activates several different receptors, and each receptor might respond to several different molecules. In addition, most things we smell have several different molecules in them, each of which is going to activate several different receptors. So the olfactory code that goes to the brain is complicated, and each of us has a different set of experiences that means our brain interprets these patterns differently. This interpretation is done in piriform cortex, on the bottom of the temporal lobe (not far from the parts of the brain responsible for forming memories!). We can’t look at a single molecule and predict what it is going to smell like to someone. But we can look at the pattern of responses across mitral cells (which get their information from bundles of synapses called glomeruli), and if the pattern is the same for two scents (for example, in the figure below, lots of action potentials from the orange mitral cell, and a few from the blue one), then the person smelling the two scents will say they smell the same.

Provided by: University of Minnesota

License: CC BY 4.0CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Biology 2e Chapter 36.3 The Chemistry of Life: Taste and Smell

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction

License: CC BY 4.0

References:

Sorokowski, P., Karwowski, M., Misiak, M., Marczak, M. K., Dziekan, M., Hummel, T., & Sorokowska, A. (2019). Sex differences in human olfaction: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 242.

Willander, J., & Larsson, M. (2007). Olfaction and emotion: The case of autobiographical memory. Memory & cognition, 35(7), 1659-1663.

Van Gemert, L. J. (2003). Odour thresholds. Compilations of odour threshold values in air, water and other media. Oliemans, Punter & Partners BV, Utrecht.