Taste and Smell

39 Flavor

Learning Objectives

Understand how the sense of smell contributes to our perception of flavor.

Understand why infants have appetitive responses to sweetness and aversive responses to bitterness.

Understand how taste and smell are affected by aging.

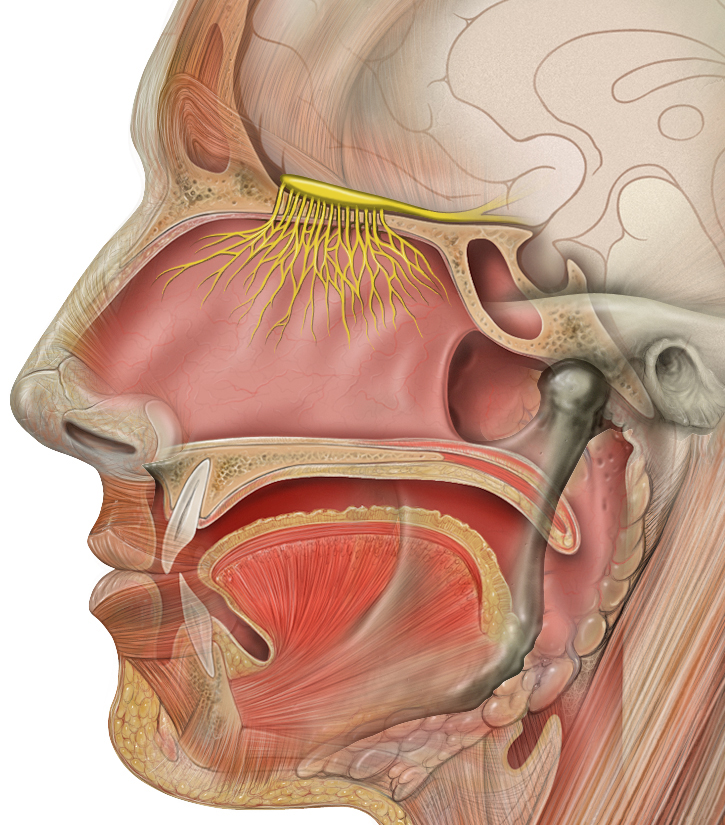

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are considered chemical senses because both have sensory receptors that respond to molecules in the food we eat and/or in the air we breathe. There is a pronounced interaction between our chemical senses in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). When we describe the flavor of a given food, we are really referring to both gustatory and olfactory properties of the food working in combination.

When we chew and swallow food, the odorants emitted by the food are forced up behind the palate (roof of the mouth) and enter our noses from the back; this is called “retronasal olfaction.” Ortho and retronasal olfaction involve the same odor molecules and the same olfactory receptors; however, the brain can tell the difference between the two and does not send the input to the same areas. Retronasal olfaction and taste project to some common areas where they are presumably integrated into flavor. Flavors tell us about the food we are eating.

The pleasure associated with sweet and salty and the displeasure associated with sour and bitter are hard-wired in the brain. Newborns love sweet (taste of mother’s milk) and hate bitter (poisons) immediately. The receptors mediating salty taste are not mature in humans at birth. Sour is generally disliked (possibly the brain’s way of protecting against tissue damage from acid). This hard-wired effect is the main characteristic of taste and is the reason why we only classify these four qualities as “basic tastes.” Our sense of taste evolves across our lifetime as we learn to enjoy all kinds of flavors while finding out which are indeed safe to eat. While the number of taste buds does not decline until after 75 years of age, there is a general decrease in taste perception as part of the aging process. Other factors that may contribute to the reduction in taste in older persons are a decrease in the volume of saliva secreted, an increase in the viscosity of saliva, and the formation of fissures and furrows on the tongue.

OpenStax, Psychology Chapter 5.5 The Other Senses

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@12.2:Nw9FOKLs@13/5-5-The-Other-Senses

License: CC-BY 4.0

Adapted by: Kori SkrypekAskA Biologist, How Do We Sense Taste?

Provided by: Arizona State University

URL: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/how-do-we-sense-taste

License: (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Adapted by: Kori SkrypekNOBA, Taste and Smell

Provided by: University of Florida

URL: https://nobaproject.com/modules/taste-and-smell

License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Adapted by: Kori SkrypekLumen Learning, Biology of Aging Chapter 8: The Special Senses.

Download for free at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/atd-herkimer-biologyofaging/chapter/taste/

License: CC BY: Attribution