Perception and Action

133 Perception and Action

Learning Objectives

Be able to explain how perception guides action.

Be able to describe how action changes perception.

Know that acting on unconscious sensory information is possible.

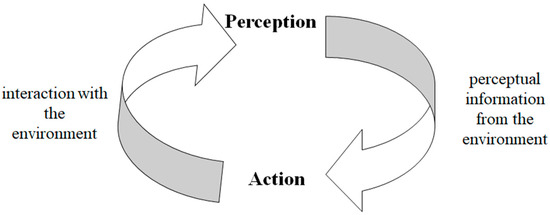

The relationship between perception and action is best described by a diagram with an arrow pointing both ways. Perception selects targets for action and helps us correct errors as we execute actions. Broadly speaking, there are 2 kinds of actions: navigation (moving around our environment) and reaching/grabbing.

Acting on unconscious sensory information is possible. There are a few dramatic examples of action without perception. For example, patient DF could mail letters through a slot but couldn’t tell you what the orientation of the slot was, and patient TN was completely blind but could navigate cluttered hallways (blindsight, Abbot, 2008). TN’s case make it obvious that visual information gets to the non-visual regions of the brain (parietal cortex) even when V1 is not working.

One line of research suggests that reaching and grasping behaviors are not always affected by visual illusions. For example, even though the Ebbinghaus size illusion is very strong, if people pinch together their fingers like they’re going to grasp the center disk, they grasp more accurately than their conscious reports of perceived size (Haffendon and Milner, 1998). Similarly, healthy controls accurately grasp a center object affected by the rod-and-frame illusion, which is the phenomenon that the orientation of a line is altered by surrounding lines or grating (Dyde, 2000). These studies suggest that all of us maintain a “raw copy” of sensory information, separate from the version that we are consciously aware of (which has been shaped by inference), to guide action. However, there is contradictory research indicating that motor planning (Craje, 2008) and reaching behaviors (Dyde, 2000) can be impacted by illusions. So it is an open and interesting question: when is our behavior controlled by illusions, and when does our motor system ignore illusions?

Cheryl Olman PSY 3031 Detailed Outline

Provided by: University of Minnesota

Download for free at http://vision.psych.umn.edu/users/caolman/courses/PSY3031/

License of original source: CC Attribution 4.0

References:

Abbott, A. Blind man walking. Nature (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2008.1328

Crajé, C., van der Kamp, J., & Steenbergen, B. (2008). The effect of the “rod-and-frame” illusion on grip planning in a sequential object manipulation task. Experimental brain research, 185(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1130-x

Dyde RT, Milner AD (2002) Two illusions of perceived orientations: one fools all of the people some of the time; the other fools all of the people all of the time. Exp Brain Res 144:518–527

Ernst, M., Banks, M. & Bülthoff, H. Touch can change visual slant perception. Nat Neurosci 3, 69–73 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/71140

Haffenden AM, Goodale MA. The effect of pictorial illusion on prehension and perception. J Cogn Neurosci. 1998;10(1):122-136. doi:10.1162/089892998563824