Taste and Smell

34 Pheromones

Learning Objectives

Know what the vomeronasal gland is and whether or not people have one.

Be able to cite arguments for and against the presence of pheromone communication in humans.

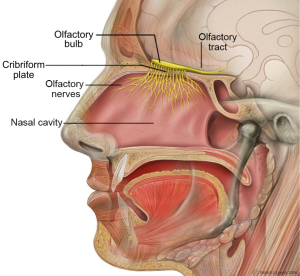

The vomeronasal organ (VNO, or Jacobson’s organ) is a tubular, fluid-filled, olfactory organ present in many vertebrate animals that sits adjacent to the nasal cavity. It is very sensitive to pheromones and is connected to the nasal cavity by a duct. When molecules dissolve in the mucosa of the nasal cavity, they then enter the VNO where the pheromone molecules among them bind with specialized pheromone receptors. Upon exposure to pheromones from their own species or others, many animals, including cats, may display the flehmen response (Fig.4.3.1), a curling of the upper lip that helps pheromone molecules enter the VNO. Humans do not have a vomeronasal organ.

A pheromone is a secreted chemical signal used to obtain a response involving a specific behavior from another individual of the same species. Pheromones are especially common among social insects, but they are used by many species to attract the opposite sex, to sound alarms, to mark food trails, and to elicit other, more complex behaviors. Even humans are thought to respond to certain pheromones called axillary steroids. These chemicals influence human perception of other people, and in one study were responsible for a group of women synchronizing their menstrual cycles (McClintock, 1971, but also see Strassman, 1999). The role of pheromones in human-to-human communication is not fully understood and continues to be researched.

Pheromonal signals are sent not to the main olfactory bulb, but to a different neural structure that projects directly to the amygdala (recall that the amygdala is a brain center important in emotional reactions such as fear). The pheromonal signal then continues to areas of the hypothalamus that are key to reproductive physiology and behavior. While some scientists assert that the VNO is apparently functionally vestigial in humans, even though there is a similar structure located near human nasal cavities, others are researching it as a possible functional system that may, for example, contribute to synchronization of menstrual cycles in women living in close proximity.

Is the effect associated with olfaction ever hard-wired? Pheromones are said to be olfactory molecules that evoke specific behaviors. Googling “human pheromone” will take you to websites selling various sprays that are supposed to make one more sexually appealing. However, careful research does not support such claims in humans or any other mammals (Doty, 2010). For example, amniotic fluid was at one time believed to contain a pheromone that attracted rat pups to their mother’s nipples so they could suckle. Early interest in identifying the molecule that acted as that pheromone gave way to understanding that the behavior was learned when a novel odorant, citral (which smells like lemons), was easily substituted for amniotic fluid (Pedersen, Williams, & Blass, 1982).

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Biology 2e Chapter 36.3 The Chemistry of Life: Taste and Smell

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction

License: CC BY 4.0

Adapted by: Jacob Weckwerth

OpenStax, Biology 2e Chapter 45.7 Behavioral Biology: Proximate and Ultimate Causes of Behavior

Provided by: Rice University.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction

License: CC BY 4.0

NOBA, Taste and Smell

Provided by: University of Florida

URL: https://nobaproject.com/modules/taste-and-smell

License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References:

McClintock, M. K. (1971). Menstrual synchrony and suppression. Nature, 229(5282), 244-245..

Strassmann, B. I. (1999). Menstrual synchrony pheromones: cause for doubt. Human Reproduction, 14(3), 579-580.