Color, Depth, and Size

107 Simultaneous Contrast

Learning Objectives

Understand the simultaneous contrast phenomenon.

Be able to give an example for this phenomenon (e.g. visual illusions).

Simultaneous contrast is the visual effect when a gray patch looks lighter when it’s next to a darker patch. This shows how fluid our perception of lightness really is.

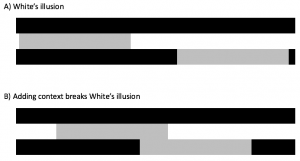

Often, lateral inhibition (phenomenon in which a neuron’s response to a stimulus is inhibited by excitation of a neighboring neuron) is used as an explanation for simultaneous contrast. But White’s illusion (below) shows that this is an inadequate explanation—the rectangles with their long sides against a white background look lighter than the rectangles with their long sides against a dark background. So we know that some other top-down effect is at play in shaping our lightness perception. There are many ways of generating context effects that create lightness illusions. What is important to remember is that our sense of lightness, brightness, and color is easily swayed by context.

Neural responses representing luminance boundaries are more credible than neural responses representing uniform patches for two reasons. First, adaptation makes it impossible to make absolute lightness judgments, so most of our perception is based on contrast and comparisons between two things. Second, the center/surround receptive field structure of our retinal and thalamic visual neurons provides weak responses to uniform fields and strong responses at boundaries. This is why we are very susceptible to lightness illusions: we know that our ability to judge lightness is weak, and we are easily swayed by what we see at boundaries and what we believe about overall scene illumination.

Fig.10.4.2. White’s Illusion. A) A rectangle surrounded by black bars looks darker than a rectangle surrounded by white bars. This is the opposite of simultaneous contrast. It probably happens because the rectangles ‘belong’ to the bars that they’re on (surface grouping), so the gray bar that looks darker is dark by comparison to the white bar that it ‘belongs’ to. Contrast along the edges is bottom-up processing; ‘belonging’ is top-down processing. B) You can break White’s illusion by letting the gray bars overlap, so they belong to each other. (Credit: Cheryl Olman. Provided by: University of Minnesota. License: CC-BY 4.0)

Provided by: University of Minnesota

License: CC BY 4.0