Proprioception: Balance and Phantom Limbs

29 Vertigo

Learning Objectives

Know how to define vertigo.

Describe the mechanism by which excess alcohol consumption results in vertigo.

Vertigo is a condition in which a person has the sensation of moving or of surrounding objects moving when they are not.[1] Often it feels like a spinning or swaying movement.[2] This may be associated with nausea, vomiting, sweating, or difficulties walking. It is typically worse when the head is moved. Vertigo is the most common type of dizziness.

The most common disorders that result in vertigo are benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, and labyrinthitis. Less common causes include stroke, brain tumors, brain injury, multiple sclerosis, migraines, trauma, and uneven pressures between the middle ears.[3][4] Physiologic vertigo may occur following being exposed to motion for a prolonged period such as when on a ship or simply following spinning with the eyes closed.[5][6] Other causes may include toxin exposures such as to carbon monoxide, alcohol, or aspirin.[7] Vertigo typically indicates a problem in a part of the vestibular system. Other causes of dizziness include presyncope and disequilibrium.

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is more likely in someone who gets repeated episodes of vertigo with movement and is otherwise normal between these episodes.[8] The episodes of vertigo should last less than one minute.[2] The Dix-Hallpike test lowers a patient quickly to a supine (lying on your back) position and typically produces a period of rapid eye movements known as nystagmus in this condition. In Ménière’s disease, there is often ringing in the ears, hearing loss, and the attacks of vertigo last more than twenty minutes. In labyrinthitis the onset of vertigo is sudden and the nystagmus occurs without movement. In this condition vertigo can last for days.[2] More severe causes should also be considered. This is especially true if other problems such as weakness, headache, double vision, or numbness occur.

Dizziness affects approximately 20–40% of people at some point in time, while about 7.5–10% have vertigo. About 5% have vertigo in a given year; it becomes more common with age and affects women two to three times more often than men.[9] Vertigo accounts for about 2–3% of emergency department visits in the developed world.

Alcohol-Induced Spins

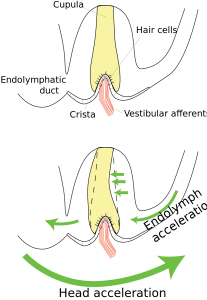

Alcohol-induced “spins” are a form of vertigo. Elevated blood alcohol content causes an increase in the density of the endolymph in the semi-circular canals, which throws the mechanics of the inner ear off. The cupula floats a bit, stimulating neurons that normally signal rotation. Thus, the sensation of spinning. Many people report that spins are worse when their eyes are closed. With your eyes open, your sense of balance has additional information (i.e., the lack of optic flow) to anchor your understanding of the world.

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

Wikipedia, Vertigo.

Provided by: Wikipedia

URL: https://psychology.wikia.org/wiki/Optic_flow

License: CC-BY-SA 3.0

Wikipedia, Spins.

Provided by: Wikipedia

URL:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spins#:~:text=The%20alcohol%20apparently%20causes%20the,in%20addition%20to%20rotational%20acceleration.

License: CC-BY-SA 3.0

References

- Post, RE; Dickerson, LM (2010). “Dizziness: a diagnostic approach”. American Family Physician. 82 (4): 361–369. PMID 20704166. Archived from the original on 2013-06-06.

- Hogue, JD (June 2015). “Office Evaluation of Dizziness”. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 42 (2): 249–258. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2015.01.004. PMID 25979586.

- Wicks, RE (January 1989). “Alternobaric vertigo: an aeromedical review”. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 60 (1): 67–72. PMID 2647073.

- Buttaro, Terry Mahan; Trybulski, JoAnn; Polgar-Bailey, Patricia; Sandberg-Cook, Joanne (2012). Primary Care – E-Book: A Collaborative Practice (4 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 354. ISBN 978-0323075855. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Falvo, Donna R. (2014). Medical and psychosocial aspects of chronic illness and disability (5 ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 273. ISBN 9781449694425. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02.

- Wardlaw, Joanna M. (2008). Clinical neurology. London: Manson. p. 107. ISBN 9781840765182. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02.

- Goebel, Joel A. (2008). Practical management of the dizzy patient(2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 97. ISBN 9780781765626. Archived from the original on 2015-07-02.

- Kerber, KA (2009). “Vertigo and dizziness in the emergency department”. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 27 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2008.09.002. PMC 2676794. PMID 19218018.

- Neuhauser HK, Lempert T (November 2009). “Vertigo: epidemiologic aspects” (PDF). Seminars in Neurology. 29(5): 473–81. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1241043. PMID 19834858.